When I called Mike Quinn this winter, he had just found out a client of his had died. She was 90, and she’d lost her husband, a playwright and writer who was also Quinn’s client, a couple of years earlier. Quinn was planning a trip to New York City to begin dealing with her estate. And to get the cat.

Mike Quinn’s a lawyer for artists. Artists need lawyers, mostly for contracts, but also for other things. Like taking on members of the wealthy Sackler family, who have been accused of fueling and making billions of dollars from the opioid epidemic. He’s fighting them and their army of lawyers on behalf of an artist friend and other opioid activists—for free. Quinn wants what his clients want: not money, but the truth. “I’m dealing with people’s hearts,” he said.

The bankruptcy of the Sacklers’ company Purdue Pharma is nearing its endgame in court. Thousands of opioid victims, tribes, hospitals, states, and other localities will vote this summer on whether to approve Purdue’s plan to convert it into a “public benefit company” and give some $4.3 billion of the Sackler family members’ money to victims and others to undo some of the damage their flood of painkillers has caused.

The truth is that those voting may not have much choice. Purdue has tried to shape a situation in which the only plausible settlement is the one Purdue offers. It’s a settlement that protects members of the Sackler family—including Richard Sackler, the former president of Purdue—from ever being held accountable in a civil court. The bottom line is simple: no liability release, no money from the Sacklers.

This is a case that shows the wealthy can have the next best thing to a private justice system, where they can pick the judge who will help them get what they want, and where ordinary people are left to deal with the fallout.

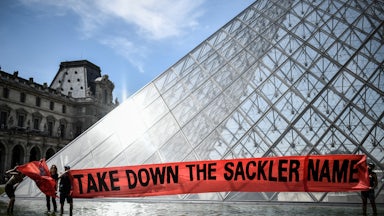

The artist friend whom Quinn represents is the photographer Nan Goldin, whose international reputation is built on an intimate, ruthless chronicling of her life and those she’s known. Goldin became addicted to OxyContin after a doctor prescribed it for tendinitis in her wrist. She lost three years of her life chasing opioids. When she got clean, she organized a group with other artists and people who had survived opioids or lost family members to opioids: Prescription Addiction Intervention Now, or PAIN. They focused on stripping the Sacklers of their reputation as patrons of the art world, with protests at some of the very institutions that supported Goldin’s work: the Metropolitan Museum of Art (which even has a Sackler Wing), the Guggenheim, the Louvre.

A mutual friend, artist Peter McGough, introduced Goldin and Quinn, and they hit it off. Soon after, Quinn showed up at a PAIN meeting. “What was distinctive when he first came around was his hair,” Goldin said. “Everyone was obsessed with his hair.... He had very big hair. Nobody could figure out what age he was.”

He was 36 at the time, with golden boy looks, the kind you see on reality TV. Which he’d actually done for a few months, as a lark, to decompress from the 100-hour weeks he’d pulled working in Big Law. He was looking for a way out, and some scout approached him on a train. Quinn thought, What the hell. The legal website Above the Law spotted him on a mercifully short-lived show on Fox called Utopia, calling him a “hottie.”

When he left the show and returned to New York, he wasn’t quite sure what to do, after having so colorfully closed the door on the world of Big Law. He didn’t want to return anyway. After representing wealthy corporations, he had made a decision: It matters who your clients are.

He had artist friends who liked that he’d done TV. He became a plus-one at gallery dinners and galas. He found his tribe, and because artists need lawyers, he started cobbling together an art law practice. Then he met Nan Goldin and joined her troupe.

Goldin remembers Quinn staying on the edge of things, at first. When she held PAIN’s first protest action at the Met, Quinn “kind of stood on the outside,” she said. “He was nervous about staying legal.” Now, he has become central to the fight to hold the Sackler family members accountable.

“He grew into one of the fiercest advocates, and this incredible lawyer,” Goldin said. “And pro bono. Against these battalions of million-dollar lawyers.”

The Sacklers’ once-sterling reputation as philanthropists has been shattered. Patrick Radden Keefe’s new book, Empire of Pain, and Alex Gibney’s documentary The Crime of the Century are the latest blows. The Sackler name is now linked to a wave of death and destruction brought on by opioids—one that critics say pretty much tracks with the spread of Purdue’s blockbuster painkiller OxyContin and its aftermath.

It wasn’t just the drug itself, which is essentially a “heroin pill,” in the words of Brandeis professor Dr. Andrew Kolodny. It was Purdue’s marketing of the pill as rarely addictive and the fix for all manner of chronic pain, from backaches to arthritis—not just cancer and end-of-life pain. The marketing campaign helped cause a major public health crisis that’s led to hundreds of thousands of deaths and an untold number of debilitating addictions.

By the fall of 2019, the company was facing thousands of lawsuits. And a number of states were advancing lawsuits against individual Sackler family members in courts, alleging they were personally responsible for helping cause the opioid epidemic.

No one in the Sackler family has ever been charged with a crime over OxyContin. Purdue has twice pleaded guilty to felonies related to the marketing and misbranding of the drug. But the individual Sacklers who own Purdue as a private company have always denied any wrongdoing. David Sackler, who served on Purdue’s board of directors, has told Congress that the family and board have acted “legally and ethically.” This is their mantra. Members of one side of the family recently posted their defenses online, while a spokesperson for another side said that he could not comment on the “confidential negotiations” surrounding the bankruptcy case, and they were focused on an agreement “that will provide help to people and communities in need.”

Facing the possibility of ruinous lawsuits, the Sackler family members and their lawyers chose a masterstroke of legal strategy: They had Purdue file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in September 2019, just as Massachusetts and other states appeared to be closing in on the individual members of the Sackler family in court. By then, Purdue had already transferred more than $10 billion to the Sackler family.

Sackler family members could use Purdue’s bankruptcy to halt all the lawsuits against them individually, hand over the besieged company, and pay a relatively small portion of the fortune they made from opioids. In exchange, they could escape a full legal reckoning of their actions and be protected from lawsuits. What they needed to do was find the right judge.

Chapter 11 is rooted in a truly American idea: It treats failure as a common consequence of the risk-taking required to create something of economic value, and offers failed entrepreneurs something in exchange for their efforts: a fresh start. The law gives judges tremendous power to protect the bankruptcy estate (in this case, Purdue’s assets) from civil lawsuits, even some brought by the states. But the focus on economics makes Chapter 11 a place where every social value—including morality, justice, and accountability—gets reduced to the only terms that matter in corporate bankruptcy: the terms of the deal.

That dynamic, combined with the way some judges have allowed Chapter 11 to be practiced, has made it a haven for organizations that want to avoid the fallout from wrongdoing—i.e., a flood of lawsuits against them—by resolving the cases without being tried on the facts. The list of organizations that have used Chapter 11 this way includes Roman Catholic Church dioceses, the Boy Scouts, PG&E, Takata (maker of exploding airbags)—and now, Purdue Pharma.

Mike Quinn’s friends and clients in PAIN were following Purdue’s bankruptcy and urging him to get involved. They wanted a way to be in the courtroom, as a kind of Greek chorus: a moral voice to remind people the Purdue case was about a lot more than extracting some money. It was about fighting to hold Purdue and the individual Sacklers accountable for their actions—and making the facts public.

After Quinn had left Big Law, the last thing he wanted was to be back there. And for anyone who’s not a bankruptcy lawyer, it’s boring. “If you don’t want to go into a big case, you definitely don’t want to go into a bankruptcy case,” Quinn said. “That’s like Snoozeville, right?” He kept putting them off.

Quinn finally agreed when he read an article about Practice Fusion. The electronic medical records company admitted to taking about a million dollars in illegal kickbacks from Purdue Pharma, to let Purdue’s marketing people tweak the prescribing software to encourage doctors to write more opioid prescriptions, even for patients who might not need them. It worked fabulously. The Justice Department said doctors who used the software wrote tens of thousands of additional prescriptions for extended-release opioids.

How do I get this in court? Quinn thought. He and his group formed a committee in May 2020 to join the bankruptcy on behalf of Nan Goldin and four others. Among them were Barbara Van Rooyan and Ed Bisch, who had each lost a son who took OxyContin.

Quinn wrote a motion arguing that there was a whole group of Purdue victims who didn’t even know they were victims. How many Practice Fusion patients got opioids when they didn’t need them? How many got addicted? Did any of them die? Quinn argued the judge should push back the deadline for filing a claim and order Purdue to use Practice Fusion’s records to track these potential victims down and notify them.

By then, Purdue had already spent more than $23 million to get the word out to the public about how to file a claim by the deadline of June 30, 2020. They figured they’d reached 95 percent of the U.S. adult population. And the judge had ruled earlier that, because OxyContin was so widely used, there was no need to notify people individually.

Pretty soon, Quinn heard from a lawyer from Purdue—and a lawyer from the committee representing all of Purdue’s creditors. They were tag-teaming. The lawyers grilled Quinn on the Practice Fusion motion. Who was he and why was he doing this? Why was he calling Purdue criminal when it hadn’t been charged with anything?

Quinn pushed back. “I suddenly feel like the Erin Brockovich of the opioid crisis,” he said with a little laugh. He asked an actual bankruptcy lawyer at his law firm to help him out, since it was all so new. “He was like, ‘Who do I bill this to?’ I said, ‘Paul, this is like social justice. We’re not billing.’” For Quinn, it was worth it even if they lost. And lose they did.

That didn’t deter Quinn. “There’s criminality, and they’re acting like this is a collections case, and that’s insane to me,” he said. He started living the case. “This is part of my being,” he said.

That was Mike Quinn’s introduction to Chapter 11, and to the Bankruptcy Boys Club. For mega–Chapter 11 cases like Purdue’s, the club is tightly knit: It’s a handful of mostly big firms and some key players. They get hired over and over again to represent the big companies that file for Chapter 11, as well as their creditors on the other side. There are a few women, but they’re mostly guys. Those at the top are among the best-paid lawyers in America. One of Purdue’s lead bankruptcy lawyers bills $1,790 an hour.

Another key player in the bankruptcy world is Judge Robert D. Drain, who the record shows was handpicked by Purdue to handle its case. It did this by filing for bankruptcy in White Plains, New York, where Drain is the only judge. “Purdue was so sure that it was getting Judge Drain,” Georgetown Law’s Adam Levitin writes in an article in the Texas Law Review, “that it pre-filled his initials on the captions of motions filed immediately after its petition, before PACER, the court’s electronic docket system, had indicated a judicial assignment.”

Before he joined the court in 2002, Drain was a partner at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP, practicing bankruptcy law. Drain is one of three judges who handled more than half of the large public company bankruptcies last year, according to figures analyzed by Levitin.

Drain possesses a literary bent. He’s published a novel, The Great Work in the United States of America, an early version of which, from his days at Yale, drew praise from John Hersey, who taught there. (A major character is an opium addict.) From the bench, he might allude to Tolstoy, Steinbeck, or Dr. Strangelove. Biblical references would not be out of line, because in this case, Judge Drain might as well be God.

Here, the law empowers a single judge to halt some 2,600 lawsuits against Purdue from opioid victims and nearly every state in the nation. What is extraordinary is that Drain has used that power to also freeze attorneys general in their tracks from investigating Sackler family members, even though they themselves have not filed for bankruptcy. It’s supposed to be a temporary power, because a federal judge stepping on a state’s sovereign powers is a serious thing, constitutionally speaking. But here, the judge has extended that temporary power 18 times since the case began in 2019. Purdue’s apparent aim is for Drain to extend it long enough for the company to obtain a deal that buries those lawsuits and kills the rights of states and opioid victims to pursue the individual Sacklers.

The attorneys general of 24 states and the District of Columbia publicly oppose Purdue’s plan. The opponents, including Massachusetts and New York, represent 53 percent of the American population. They have tried to persuade Drain to let them gather more evidence to test their claims against individual Sackler family members in court. That’s the best way, they say, to help them decide whether to settle, and on what terms.

Drain does not agree. He believes his courtroom is a better venue to help Purdue’s opioid victims than a “litigation festival.” And he seems to believe that tying the hands of victims and states in their efforts to go after Sackler family members will help accomplish that. “A trial is at best a limited way to get to the truth,” he said in court. “It doesn’t result in the truth, it results in a ruling or a verdict.… Now, there are trials that, you know, people stand up and say, I did it, but that usually happens on Perry Mason only.”

Georgetown’s Levitin calls Drain’s action “the camel’s nose under the tent” that will likely lead to shielding the individual Sacklers from any legal action—without any of them facing trial.

Drain also apparently believes that sharing too much information with the public during the case is a bad thing.

He’s allowed Purdue to use members of its own board of directors to investigate Sackler family members, and he has allowed Purdue to keep many details of that investigation secret. He took the unusual step of privately asking members of the Sackler family to remove from the docket their request to make public a 580-page presentation that outlined the family members’ defenses. He said making the information public would “severely retard the progress of this case.”

Drain has said in court that sometimes the “only way to get to true peace” is to grant people who aren’t in bankruptcy the kind of liability release the family members are banking on. It is Drain’s support for “nonconsensual third-party releases” that makes him so valuable to the individuals. For them, getting one of these releases is like being blessed and forgiven and skipping the Go and Sin No More speech.

Purdue filed for bankruptcy in the Southern District of New York. Had it filed in the Manhattan office, Purdue might have drawn a colleague of Drain’s, Michael Wiles. Wiles is highly skeptical about the power of bankruptcy courts to shield people outside bankruptcy. By filing in White Plains, Purdue dodged the gamble of getting a judge like Wiles.

In May 2020, Mike Quinn joined the bankruptcy with his five clients, as the Ad Hoc Committee on Accountability. “Basically every community across America was suffering, is suffering, from the opioid crisis,” he said. “You shouldn’t concentrate a decision that affects every community to one court and one particular judge. It’s dangerous.” He wound up mixing fighting in court with guerrilla warfare. Later, he would turn to something I can only describe as legal performance art.

Quinn grew up in the Hudson Valley, about two hours north of New York City. He’s living out the pandemic in his childhood home, a 1790 Colonial. Both his grandfathers were judges, and he thinks about them these days. When he got into the Purdue case, it struck Quinn that his grandfather, Joseph Quinn Jr., who was a New York State Supreme Court justice, had upheld the draconian Rockefeller drug laws, while Quinn was now standing for people whose lives had been damaged by a man-made flood of opioids. His other grandfather, Jack Garrity, was a U.S. magistrate and city court judge in Poughkeepsie, New York, with a sense of humor on the bench. Quinn has brought a lot of humor into this case.

“Humor is humanity,” Quinn said. “I think I use it as a reminder that this case is about life and death. Not about some mall developer skipping out on his debt.” To Quinn, the fact he’s even in this case is funny. “I’m an art lawyer. What am I doing here? Why am I the moral voice in this?”

Quinn wasn’t the only one who thought Sackler family members were using bankruptcy court to hide the truth. On July 22, 2020, The New York Times published an op-ed with the headline “THE SACKLERS COULD GET AWAY WITH IT.” It argued they were using bankruptcy to avoid being held accountable for their actions and also to hold on to much of their wealth from opioids. It concluded the bankruptcy court was likely to give them their way.

At a hearing the next day, Drain lashed out at the media and suggested people not read press coverage of the case. The next week, Quinn appeared in an article in The Intercept about the Purdue case. And in August, Quinn was the only person interviewed for a piece in The Guardian, which somehow obtained a long-sought internal memo from the Justice Department’s first case against Purdue for its marketing of OxyContin, during the George W. Bush administration. It revealed that in 2006, career prosecutors had wanted to indict Purdue for felonies of mail fraud, wire fraud, money laundering, and conspiracy—and to indict three Purdue executives with felonies. Instead, after negotiating with lawyers and lobbyists for Purdue and the Sackler family members (Rudy Giuliani was one consultant to Purdue), the government settled the case against Purdue in 2007 with a single felony charge of misbranding OxyContin, and a misdemeanor for the executives. It levied fines—then buried the supporting documents. Quinn’s message in The Guardian was: Don’t let it happen again.

Quinn and others believe the kid-glove handling of Purdue in 2007 was a mistake that led to the worst of the opioid crisis. After that, Purdue continued its aggressive marketing of OxyContin. Deaths from opioid overdoses kept rising. And Purdue transferred more and more of its money to Sackler family members. Their wealth is now estimated at $11 billion.

In September 2020, Quinn filed an objection to Purdue’s latest request to continue stymieing the opposing states and victims. He asked how creditors could decide whether a settlement is fair, when the investigation of Sackler family members was being done in secret. And he raised the issue of how Purdue got its case before Drain in the first place: “If Purdue has been able to select the Court it wants to hear its bankruptcy case, that Court should be especially reluctant to shut down all litigation against the Sacklers elsewhere. To do otherwise encourages manipulation that is clearly not in the public interest.”

Quinn cited remarks Drain made in court that suggested the judge badly wanted a global settlement with the Sackler family members. “In its efforts to encourage a settlement,” Quinn wrote, “it appears that the Court has placed a thumb on the scale in favor of the Sacklers.”

Four days later, The Wall Street Journal published an article about Purdue’s judge-shopping. A company spokeswoman said it was proper, because “White Plains is about 15 miles from our corporate headquarters, and is the closest federal bankruptcy courthouse.” Two days later, Drain granted Purdue another extension that protected the family members. When an attorney for the creditors made an offer to share some information about Purdue with Quinn, Drain interrupted him.

“I would not want this five-person group, which has already made unfounded and inflammatory statements, to go into such a review untethered by confidentiality,” he said. “I just don’t trust them.”

Two weeks before the presidential election, the Trump Justice Department announced it had settled its civil and criminal probe of Purdue with three felony charges against the company for fraudulently marketing its extended-release opioids and paying kickbacks to sell more opioids. But no one at Purdue was charged. “It was as if the corporation had acted autonomously, like a driverless car,” Patrick Radden Keefe wrote.

A separate Justice Department settlement with individual Sackler family members said they “exercised substantial oversight over management’s operations of Purdue.” But none were charged criminally. They agreed to pay a fine but did not admit responsibility.

The settlement was a powerful aid to Purdue and the Sackler family members to get what they wanted in bankruptcy court. It boils down to this: The DOJ settlement contains a “poison pill” that could leave victims and states and other creditors with nothing unless they approve the bankruptcy deal Purdue offers. And oddly, it requires Purdue to do exactly what Purdue wants: to continue to restructure as a public benefit company.

Why would the Justice Department care about whether an opioid business survives? Why would it go so far as to mandate how it would survive? That’s not clear. What is clear is that if Purdue were liquidated, as some states and victims wanted, the judge could not force creditors to accept a liability release for the individual Sacklers without their consent.

As Sackler family members pushed the judge to approve the settlement quickly, Quinn told the judge his client Barbara Van Rooyan—who had testified against Purdue back in 2006—had dreamed about her son after hearing the news. Drain approved the DOJ settlement in November.

In February of this year, Quinn wrote a letter to the U.S. trustee’s office—the public’s bankruptcy watchdog—raising questions of a potential conflict of interest he’d detected in the billing records. While scanning the eye-popping bills (as of April, they totaled more than $380 million), he’d noticed something weird, later confirmed by the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP and another of Purdue’s law firms hadn’t disclosed they had a preexisting deal with lawyers representing members of the Sackler family to keep information shared between them confidential and to share litigation strategy. In bankruptcy, that deal may conflict with Purdue’s legal duty to everyone the company owes money to, since that duty could require the company to go after the Sacklers.

Skadden responded that the firm had done nothing improper. But in late April, Clifford White, the director of the United States Trustee Program, announced his office had required the two firms, as well as a third, to waive $1 million in bankruptcy fees for failing to adequately disclose the agreement to the court. In fee terms, it amounted to a parking ticket, but White said the lapse was “particularly concerning because a central question in these cases has been the independence of Purdue from the Sackler families.” Out of hundreds of lawyers in the Purdue case, the only one to raise the issue was Mike Quinn.

In March, Quinn filed an objection to Purdue’s latest request that the judge prevent victims and opposing states from pursuing the individual Sacklers in their courts. “Almost twenty years ago,” Quinn wrote, “when Richard Sackler was President of Purdue, his friend wrote him: ‘I hate to say this, but you could become the Pablo Escobar of the new millennium.’” The Colombian drug lord’s palatial compound was called “La Catedral.” Quinn said the Sacklers were using Purdue’s bankruptcy to hide from justice, and to hide much of their money. “This bankruptcy,” Quinn wrote, “is the Sacklers’ cathedral.” At the next hearing, Drain extended the injunction against the opposing states one more time. In April, Quinn’s objection to Purdue’s latest request to extend the injunction focused on a topic the judge had lectured Quinn about in March: a set of factors a court should consider in approving a settlement.

One of these factors concerns “the experience and knowledge of the bankruptcy court judge.” Quinn wrote that he and his clients didn’t believe any case should depend on the selection of the judge.

“The committee has observed a pattern, in which mega bankruptcies are often brought to the same small group of lawyers and judges,” he wrote. “Those lawyers and judges produce settlements…. A specialized practice evolves.” Quinn compared these lawyers and judges who secure liability releases for people who aren’t in bankruptcy to “finches in the Galapagos,” who through natural selection would “take over their island and grow giant beaks to gobble up the system of justice.”

He followed that with an image of Darwin’s finches that is now part of the permanent, official record of In re: Purdue Pharma L.P., et al.

At the next hearing, Drain granted Purdue’s seventeenth extension. And then he said this to Quinn, “You’re lucky that I’m a restrained judge. I could hold you in contempt for that pleading. Including the art work.” He added, “Clean up your act!”

The next day, there was a rumor that there would be no transcript of the previous day’s hearing, because the hearing hadn’t been recorded. “The hearing was not recorded due to an internal error,” Eddie Andino, the divisional manager, told me by phone later. When I asked whether the error was technological or human, he said, “Yes.”

I asked whether this was rare or typical. “It’s super-unusual. It’s happened maybe once or twice before, but it’s very rare.” When I asked about the other occasions, he said: “That I’m not going to comment on.”

“I was trying to bring the world into the bankruptcy,” Quinn said. “They want to keep the world out of the bankruptcy.”

Quinn told me, “If you look at the entire case from the DOJ to the bankruptcy, that’s the problem: We’re never going to know what the individual Sacklers did. They’ve used government entities to be able to keep that truth to themselves. That’s what’s messed up.”

But he said there had been moments when he felt his clients were being heard through him. “The whole purpose of this is just to fight—it’s not about the outcome.... The outcome is out of your hands.”

Temple law professor Jonathan Lipson was among those who tried and failed to persuade the judge to name an independent examiner to get to the bottom of what the Sackler family members did and what their true liability should be—based on the evidence. He said this about Mike Quinn: “I think Mike’s contributions have been incredibly valuable. These arguments have to be made by somebody, and the folks that ordinarily would make them for whatever reasons are not making them. So Mike is sort of the only guy out there. And, you know, he’s on the side of the angels.”