In four minutes on Season 3, The Sopranos nails the ethical dilemma that has long mired the art world. Carmela Soprano’s consultation with the Jewish shrink is priceless: Facing the truth about Tony, her mob-boss spouse, the upscale Mafia housewife tries to compartmentalize her marriage from its funding sources. She is loath to divorce. “Us Catholics, we place a great deal of stock in the sanctity of the family,” she explains. He bluntly advises her to leave: “You’ll never be able to quell the feelings of guilt and shame as long as you’re his accomplice.” “All I do is make sure he has dinner on his table,” Carmela insists. “So ‘enabler’ would be a more accurate job description,” the therapist schools her. “I’m not charging you, because I won’t take blood money, and you can’t either. One thing you can’t say is that you haven’t been told.”

Like pious Carmela in her haute bourgeois drag, art museums are married to the mob. They want to be seen as temples to the creative spirit untouched by the ruthless machinations of capital, a blameless zone of public service, but a quick scan of their patrons reveals the truth. Asserting their sanctity, museums gentrify a rogue’s gallery of funders: banksters and hedge fund managers, fossil fuel oligarchs, private-prison and opioid profiteers. They demonstrate little compunction about art-washing predators whose business models are as antisocial as Tony’s. From the robber barons of yore—Frick, Carnegie, Rockefeller, etc.—to today’s one percent, it is a hallowed tradition for apex greedheads to seek the halo of philanthropy by supporting the arts. Museum boards are crowded with the worst of the moneyed elite, permitting them to launder their reputations for plunder and pelf as they impress their rivals with lavish tax-deductible donations, reap prestige, and celebrate themselves with galas. Their philanthropy is socialism for the rich, an expression of everything wrong in our grotesquely unequal republic—“freedom’s land,” as Gore Vidal would say, “bravery’s home.”

Museum development departments market art-world cachet as tax-deductible corporate PR. It’s their de facto business model to custom-craft “collaborations” for sponsors as a strategy to defuse public concerns and deflect criticism. As a festering symptom of our culture’s capture by corporate interests, until very recently, this symbiotic relationship has caused not outrage but resignation, even abject appreciation—until, that is, the flurry of scandals that brought the whole devil’s bargain into public view. On both sides of the Atlantic, artists and activists have agitated effectively enough to oust a few choice specimens of the dirty-handed rich, among them tear gas magnate Warren Kanders, who resigned as vice chairman of the board of the Whitney in July, after eight artists pulled out of the Biennial in protest.

These events mark a significant disruption of the status quo. Art professionals (i.e., curators and staff) who wanted to advance (nay, survive) have historically had to be courtiers to the rich, willing to self-censor any gauche tendencies that might rub their patrons the wrong way. Such complicity with sponsors has been baked into the system since the 1970s, when NEA cuts threw arts organizations to the tender mercies of the marketplace. The tax break, according to the National Endowment for the Arts, has become “the most significant form of arts support” in the United States, where charitable donations to the arts far outstrip governmental financing.

The contradiction between the lofty stated values of the museum and the predatory exploits of its patrons would be great fodder for satire if it were not so deeply disturbing. Consider the Museum of Modern Art’s expansion, coming this October. “The museum didn’t emphasize female artists, didn’t emphasize what minority artists were doing, and it was limited on geography. Where those were always the exceptions, now they really should be part of the reality of the multicultural society we all live in,” said MoMA chairman and vulture capitalist Leon Black, whose former family charity director was prominent creep Jeffrey Epstein. Also creepy: Black’s fellow board member Larry Fink, who is the CEO of BlackRock, the second-largest investor in private prisons, which serve their for-profit goals at the expense of incarcerated populations, overwhelmingly people of color. The appalling Carmelaesque hypocrisy of these institutions, masking their dependency on dirty money with flamboyant shows of identity sensitivity, shocks nobody because it is simply business as usual. The new wing boasts a $50 million gift from trustee Steven Cohen, whose trusty Point72 hedge fund was created after his former firm, SAC Capital, pleaded guilty to fraud. I’ll go out on a limb here and predict that the wing will be hailed as progress.

Last spring, Decolonize This Place (DTP), a collective of two dozen activist groups working against colonialism and gentrification, targeted Kanders, who has supported museums as a “safe place for unsafe ideas” while profiting from the violent repression of immigrants, dissidents, and other hapless losers of neoliberal empire. Kanders’s Safariland “defense products,” as they are euphemistically called, have been used against protesters at Standing Rock and Ferguson and migrants at the Mexican border. The activists’ open letter to the Whitney mounted a powerful critique of the museum’s complicity with historic and present injustice. “We know this goes beyond Kanders,” the signatories wrote. “He is a stand-in for an entire system.” For months, despite weekly demonstrations, Kanders refused to step down.

But in July, his reluctant hand was forced by a piece in Artforum co-written by Hannah Black, Ciarán Finlayson, and Tobi Haslett, who argued that artists were being “instrumentalized to cleanse Kanders’s reputation,” and called for participants in the Whitney Biennial to withdraw before the show closed in September. Kanders, they wrote, may be no worse than others on boards around the country, and capitalist accumulation depends on the “exploitation, misery, and boredom of people all over the world,” but these facts make it more, not less, important to act when there is a chance to do so. Eight artists, including standout star Nicole Eisenman, responded to the call by pulling out.

CODE PINK and Art Space Sanctuary, which disrupted MoMA’s annual David Rockefeller awards to protest MoMA board member Larry Fink and honoree Brian Moynihan, of Bank of America, made a similar point of targeting the system, not the individual. The protesters demanded that the museum, and Fink, “divest from private prisons in the U.S.” “The goal of the campaign,” they explained to Hyperallergic, was “not for Fink to resign from MoMA’s board but instead to call attention to museum practices in the U.S. that are complicit with oligarchical structures.”

Meanwhile in the U.K. protests against ecocidal art patron BP have been heating up. The activist group BP or Not BP? has staged massive protests at the British Museum, where the gas company’s contract runs through 2022, and has twitted the upcoming BP-sponsored blockbuster Troy: Myth and Reality as a “Trojan Horse for BP.” English actor and director Mark Rylance recently resigned from the Royal Shakespeare Company, refusing to be a stooge for BP, whose toxic sponsorship, he eloquently argued, is inconsistent with the RSC’s stated values. Egyptian novelist Ahdaf Soueif stepped down from the British Museum’s board of trustees in July, troubled by BP’s sponsorship, the corporation’s lack of engagement regarding the repatriation of artworks, and the museum’s treatment of its own contract workers. As she wrote in the London Review of Books: “The world is caught up in battles over climate change, vicious and widening inequality, the residual heritage of colonialism, questions of democracy, citizenship and human rights. On all these issues the museum needs to take a clear ethical position.”

Before Kanders resigned, he went as far as to applaud the protesters’ “bravery” and praise the institution where for so long he was safe from accountability. “I am not the problem,” he replied to a collective “boo!” signed by 100 Whitney staffers back in November 2018. Whitney director Adam Weinberg stood with Kanders for months, announcing he welcomed the demonstrators’ “dissent,” even as he reasserted the museum’s mythic autonomy. “The Whitney cannot right all the ills of an unjust world,” Weinberg unnecessarily reminded us. For a long time the Whitney was perfectly happy to welcome the DTP protesters as a badge of its enlightenment and open-mindedness, while Kanders brazenly profited from practices that directly contradicted the museum’s claim to respect diversity. With a few small gestures, the spectacle of dissent was safely absorbed into the Whitney brand borg. This is how The New York Times describes art museums’ preferred stance: “They want to stay above the fray.” Carmela Soprano would doubtless nod sagely in agreement.

In the irony-free zone of self-satisfied global philanthropy, systems of mass surveillance lord over amoral flows of capital, while its architects dole out awards for freedom of expression. Take Yana Peel, please. Until recently the CEO of London’s Serpentine Galleries, the glamorous “freedom of speech advocate,” as she styles herself, championed star Chinese dissident Ai Weiwei while funding spyware sold to police and authoritarian governments to target dissidents and journalists. Peel chanted Kanders’s mantra (the museum is “a safe place for unsafe ideas”) as she swanned her way through shmancy art and fashion circles. When The Guardian reported Peel’s indirect ownership of her husband’s spyware business, the artist Hito Steyerl pulled her artwork from the Serpentine’s web site in protest (although she did not sever ties with the gallery completely). Peel swiftly resigned, shamelessly declaring herself a victim of “bullying”: ‘‘If campaigns of this sort continue, the treasures of the art community—which are so fundamental to our society—risk an erosion of private support.” Such a reversal, she lectured the public, “will be a loss for everybody.” A “very happy” Steyerl told the Times, “the Serpentine Galleries set a strong precedent by reacting quickly thus living up to their stated values.… a valuable example for art institutions worldwide.”

Yet the more the museum “supports” dissent, the more effectively it muddles ethical choice: Do we support using tear gas on civilians—or not? Do we support fossil fuels? And if not, why did we countenance BP-sponsored blockbusters or a tear gas magnate on the board of the woke Whitney? Is the climate crisis and a police state the price society must pay to support the arts? Art-washing—whereby greedsters trade filthy lucre for cultural capital, civic glory, and good PR—thrives by muddying the moral waters.

It isn’t surprising that the erstwhile Serpentine CEO (and Goldman Sachs alum) could applaud herself as a freedom-of-speech advocate while she funded spyware. At the highest brackets, the more incoherent the agenda, the more potent the art-washing: The super-suds of the museum transform surveillance into freedom of speech, exploitation into art patronage, and refugees into a detention-center revenue stream and MoMA’s glamorous new diversity wing. Elite impunity apes legitimacy. We live in a “market-driven art world characterized not so much by impassioned manifestos as exclusive dinners with collectors,” gushes The New York Times. “Today everything is nice, everything is accepted. And nothing makes any sense,” muses artist Daniel Buren, whose formerly controversial works of institutional critique are now rendered anodyne and safe by their status as blue-chip Art.

Enter the opioid crisis. The perfect morality play, it has a heroine, Nan Goldin, a prominent photographer and recovered opioid addict whose activism via P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) targeted a clear villain, the Sacklers of Purdue Pharma. Under the Sacklers’ watch, Purdue aggressively and dishonestly marketed OxyContin as a less-addictive painkiller, while the (crime) family lavished their ill-gotten gains and moniker on elite museums worldwide, including the Guggenheim, the Met, and the Tate Gallery in London. As a trophy brand and blue-chip art commodity herself, Goldin has clout unavailable to less prominent artists, and the courage and integrity to use it.

Inspired by the success of ACT UP, an activist group that fought the AIDS crisis, Goldin launched her direct-action campaign in 2018 with dramatic “die-ins” at Sackler-branded galleries at the Guggenheim, the Met, Harvard, and, most recently, the Louvre. Offered a retrospective by the National Portrait Gallery in London, Goldin refused to cooperate unless they shunned Sackler funds. In March 2019, the NPG rejected a $1.3 million donation from a branch of the Sackler family. Today, rare Sackler holdouts include London’s Victoria and Albert Museum and the Brooklyn Museum, which stands behind Elizabeth Sackler, who funds its Center for Feminist Art. In pre-OxyContin days, Elizabeth’s father, Arthur, merely pioneered aggressive marketing to hook housewives on Valium. Two generations, each in their own way mother’s little helper.

P.A.I.N. effectively turned the Sacklers into pariahs whose money is now too filthy to art-wash: Sackler pecunia olet. (The New York Post reported disgraced Sacklers fleeing Manhattan to seek refuge in Palm Beach. The humanity!) The Sacklers are odious but so are all the one percenters who fund the elite art world when you look into the sources of their excessive wealth. Donald Trump has galvanized current antagonisms, yet he inherited a system that was already dramatically skewed in favor of the rich. The financial crisis afforded Barack Obama an opportunity to discipline the institutions that created it, but instead, he chose to enable them. The bailouts showered the crooks with money and gutted the middle class. There were some ten million foreclosures, while not a single Wall Street CEO was prosecuted. People of color were hardest hit. It’s a particularly cruel irony that the nation’s first black president oversaw the extinction of the black and Latino middle class, not to mention the further immiseration of the poor. To manage public frustration that no one was held accountable for this unconscionable transfer of wealth, the bipartisan elite welcomed identity politics as a way to deflect attention from economic justice issues, even fanning, at times, a false tension between the two.

Both arts organizations and the art market have long been abject courtiers to corporate and private bucks. But this shtick didn’t become really awkward for museums until the social-justice set racialized the issues. Protests against Kanders and Fink stress how their enterprises prey upon minorities, a powerful embarrassment for wannabe woke art institutions. Demands for diversity mean a great deal to these organizations, which pride themselves on their enlightened cultural politics and commitment to equality. Populist outrage over financial predation has had more trouble hitting the mark. Or to put things a tad more plainly: Diversity demands have traditionally fueled the most embarrassing PR debacles in the art world—and they are also quite easy to accommodate without disrupting the economic status quo.

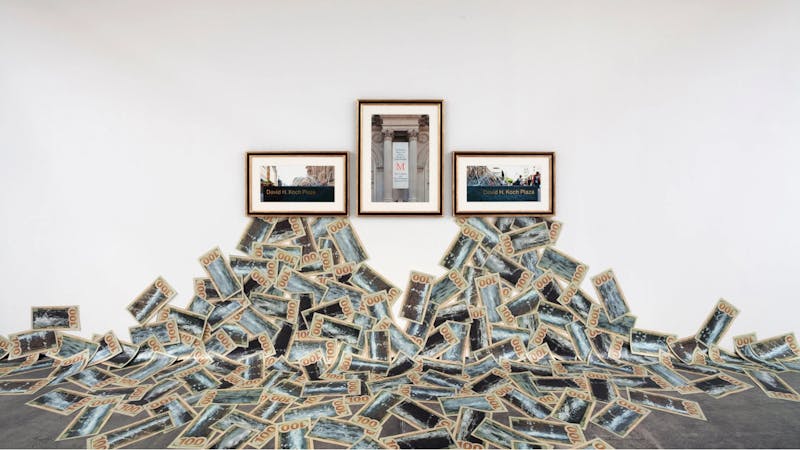

In the 1970s, Hans Haacke trailblazed what the art world calls “institutional critique,” a kind of art that, when it appears now, often feels like little more than a hollowed-out gesture. But Haacke went for the jugular, merely following the money to devastating effect. His systemic view of the museum’s role in the capitalist food chain is stunningly damning. The classic “On Social Grease” (1975) consists of six magnesium plaques suitable for a corporate lobby. Inviting the viewer to connect the dots, Haacke juxtaposed quotes from industry and museum leaders to highlight the rhetoric melding funding of the arts with good business practice. Here, for example, is a good one from Robert Kingsley of Exxon: “Exxon’s support of the arts serves the arts as a social lubricant. And if business is to continue in big cities, it needs a more lubricated environment.” Haacke’s “MetroMobiltan” (1985) deploys museum-style signage to juxtapose images of violence in South Africa with a Mobil-sponsored art exhibition in New York City, pointing up Mobil’s ties to the apartheid government as well as to the Met. One panel quotes a Met pamphlet pitching “many PR opportunities” custom-crafted for sponsors in the bland pseudo-neutrality of museum-speak: “These can often provide a creative and cost-effective answer to specific marketing objectives, particularly where international, government, or consumer relations may be a fundamental concern.”

Museums’ chumminess with industry got a boost from the “culture wars” of the late ’80s, when art battled censorship by wingnuts who then took aim at the NEA. Homophobic Jesse Helms was triggered by Robert Mapplethorpe. Rudy Giuliani was pissed off by Andres Serrano’s “Piss Christ” and Chris Ofili’s turd-embellished portrait of the Madonna (recently donated to MoMA by trustee Steve Cohen). Contending with the NEA cuts, museums turned to corporate sponsors for a bailout, Haacke explains in the essay “Museums, Managers of Consciousness.” Philip Morris donated to Helms (an ultraconservative senator from North Carolina), and gave even more to vulnerable arts organizations, resulting in such cozy arrangements as a branch of the Whitney inside the corporate headquarters of Philip Morris.

“Practically all institutions have accepted the domination of the public sphere by corporate interests,” Haacke observed in 2004. “Many of them without offering much resistance and without embarrassment.” For decades, museums have colluded to soften the public image of toxic funders, to disconnect the vicious sources of their wealth from its salubrious potency to fund art (even though such funding is almost always underwritten at taxpayer expense). Haacke’s powerful oeuvre reconnects those dots. Shrewdly leading with identity, the DTP coalition acted on Haacke’s systemic critique, wielding the woke museum as a PR tool to target Kanders’s reputation rather than launder it. And thus the coalition attached a human face to the violence of an exploitative, immoral economic system that profits by immiserating the very identity groups the museum is taking such pains to celebrate. Unfortunately, as outside protesters, they had zero leverage with the Whitney.

Following the money is important and tricky. The rot of predatory capitalism must be solved first and foremost by economic justice. That museums must diversify collections and staff is self-evident, yet to focus only on diversifying them—without dismantling structures of funding and reward, in efforts financed by predatory capitalists who continue to profit from exploitation—allows business to go on as usual, now with woke optics. What if elite identitarian groupthink has it backward? Racial discourse has been used to justify exploitation for centuries. Yet attempts to avoid racism have a treacherous way of instantiating racist frameworks and ways of thinking. Why is the notion of working toward racial equality so often presented as an “alternative to an egalitarian program of redistribution,” as Adolph Reed Jr. puts it, rather than part of the same project? Perhaps because separating these concerns helps the overlords keep the status quo essentially in place.

In the art world, curating by identity has been embraced as a gesture to rectify historic injustices. The importance of including historically overlooked groups can’t be overstated, but for artists, the emphasis on identity has a downside. People now focus on demographic attributes—and market value—more avidly than the work itself. Rooted in history and a web of social relations—including the central fact of how the business of art is funded—art is also a realm of invention, transformation, play, magisterial thing-ness. Identity, the current lingua franca of art marketing, is integral to some artists’ practice, but it is not the main driver of the work of many others. Elena Crippa, curator of the recent Frank Bowling exhibition at the Tate, said that the Guyana-born British artist “rejected being categorized or pinned down as being either a black artist belonging to the Windrush generation or anything else.” Bowling wanted the show to focus purely on the formal aspects of his work rather than his life story and his race. “I don’t know what black and Asian art is,” he commented. “I know what art is art.”

Bowling’s wish for his work to be taken on its own terms—not reduced to tribal affiliation—used to be shared by many artists. Today, artists are professionalized to package their identity as part of their brand—whether they do it themselves, or it is done to them, sometimes to the artist’s dismay. The push to see art through the prism of identity says more about our current political climate—and institutional pressures—than it reveals about art, and many artists.

This year’s Whitney Biennial, which became a lightning rod for anti-Kanders activism, was conspicuously diverse in both the gender and ethnicity of its participants, an overachievement that the curators hailed as a breakthrough effort to reflect “a snapshot of art in the United States” (and perhaps unwittingly, ageism—most of the 75 artists were under age 40, 20 of them younger than 33). Reviewers took the census: “More than half of the artists were women”; “four identify themselves as gender non-conforming”; and “more than half belong to racial or ethnic minorities,” including eight “identifying as Native American.” At the opening, a veteran artist channeled the curators: “They’re on an Easter egg hunt,” she chuckled. “Oh look, I found one of these, one of those—look, a purple one!” She noted only three artists born before 1960 who weren’t dead. (“I’m going to put in my will, ‘Don’t include me when I’m dead!’” she told me. “If they don’t give me a show before then....”) The show fetishized the young discoveries along with a handful of overlooked olds, sprinkling in a few stars to validate everyone else.

Not many artists—even in “freedom’s land”— have the appetite, the chutzpah, or the clout to risk ruffling patrons’ feathers. In a self-obsessed culture, identity politics suit institutional diversity goals—and flatter the woke global elite—while systemic critiques of capitalism (and its gentrification, awkward!) are effectively marginalized. (The notable exception is Haacke, who remained influential, though banned from U.S. museums for many years after a notorious incident at the Guggenheim, where he documented the holdings of a slumlord whose ties with the Gugg remain unclear. The show, in any case, was canceled. Edward Fry, the curator who defended Haacke, was also effectively canceled, never again to work in a U.S. museum.)

Of course, there are always those who are fine with going along to get along. The higher up people are in any organization, the more socialized they are not to rock the boat. A highly placed curator I know gets positively giddy hobnobbing with rich collectors and donors; it sends a thrill up his leg! Meanwhile, the world burns. While most art world denizens deplore the patriarchy, racism, the climate crisis, Trump, etc., their curiosity usually stops short of the financial predators whence spring the obscene amounts of money sloshing around the global art market—a willed ignorance that enables the grotesque transfer of yet more wealth and cultural prestige to the one percent. In such circles, the complexity of oligarchy and its Orwellian tentacles induces glazed eyes, if not learned helplessness by design.

As the Whitney patronized DTP’s nine-week-long spectacle of dissent this spring—a multiculti ruckus in the museum lobby and galleries, burning incense to purge colonial vibes, even marching to Kanders’s nearby digs in the now turbo-gentrified Village, where protesters held a rally and left Kanders a “larger-than-life model of a Safariland tear gas canister”—one might have held out some hope for claiming the museum world as a preserve of social-justice allyship. Or again, more skeptically, one could have been forgiven for thinking the increasingly woke museum is yet the newest gambit to preserve the stranglehold of the ruling elite (who continue, in the broader scheme of things, to profit from distinctly unwoke border detention centers, the militarized police, surveillance of dissidents and journalists, looting and plunder for shareholder profit, and looming ecocide). Recall Walter Benjamin: “There is no document of civilization that is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

Lest I be unclear: Of course arts orgs should not enable toxic donors. Philanthropy is not an adequate alibi for exploitation. Greed is not respectable and should be shamed with relish! When predators are exposed, cultural institutions should support transparency, not permit bad-doers to hide behind the museum’s skirts! (And Carmela should leave Tony, if she doesn’t approve of the family biz.)

Like Carmela, museums are past masters at putting a respectable face on barbarism. In an increasingly woke world, it is no longer possible for them to deflect outrage. The danger comes when we allow identity politics to placate social-justice concerns without fully addressing elite impunity for an exploitative, immoral economy that also happens to be wrecking the planet. Deployed in this all-too-common and cynical fashion, identity politics are to museums what tax-deductible philanthropy is to the rich: an acceptable way to neutralize dissent and bury past and present crimes.

What is to be done? The answers are as simple as they are hard to carry out: Institute tax reform to undo the current feudal model, redistribute the wealth the one percent has filched from the people, provide direct public funding for the arts (not funneled first through greedy plutocrats).

Until then, on the all-important battlefield of PR, Nan Goldin, Hito Steyerl, and the Whitney dropouts have shown that prominent artists are best positioned to take on toxic patrons by refusing to let them trade on their prestige. Thanks to Goldin’s P.A.I.N. (as well as oodles of lawsuits and a searing New Yorker exposé), the Sacklers are worldwide pariahs—whether or not their name continues to tag museums like a deluxe badge of greed. (Removing the names is a symbolic gesture, and a legal question, in many cases, negotiated by the drug-pushers for their “generosity.”) Thanks to Steyerl, the Serpentine will no longer drape Peel’s creepy surveillance “investments” with respectability. Imagine if more art stars repeated Goldin’s powerful gesture when she refused a retrospective at London’s National Portrait Gallery unless it cut ties with the Sacklers. The museum met her demand, Goldin’s career thrives, and she has set an example of artistic integrity and ethical courage that is now emboldening others.

More and more critics are coming around to Goldin’s position that “direct action is our only hope.” When MoMA’s much-anticipated expansion opens this fall, bad-acting donors such as Fink should be tied to its tail like a rattling tin can. With this disgraceful connection firmly fixed in the public mind, no one can look upon the new woke wing of MoMA without also pondering what paid for it: odious “investments” in detention centers, those de facto prisons that target the same overlooked populations the museum’s galleries now welcome.

MoMA’s annual Party in the Garden is a swanky fund-raiser that was picketed last year by underpaid MoMA workers, who protested “Modern art, ancient wages.” Hoping for another action, perhaps to target prison-profiteer Fink, I showed up early this year, but alas, no demonstration. Instead, I looked out on the Midtown tourist district’s canyon of luxury development and sleek corporate towers. Fifty-third Street on that glorious May evening oozed money—and its lack. A few doors away from MoMA, bedded down on a concrete bench, backpack for a pillow, lay a gentleman sleeping. I lurked near the entrance, where, disgorged by their shiny town cars, the discreet and pampered VIPs sauntered in.

From my post I eyed collector and dealer Adam Lindemann, the militantly high-end shopper who crusaded against art fair looky-loos in 2011, rabble-rousing his fellow spenders to “Occupy Miami Basel”—a social protest every bit as perverse as its sounds. His gallerist partner, Amalia Dayan, accompanied him in pointy S&M attire: a sharp-shouldered gunmetal-gray jacket, tight skirt, and bondage heels (to stomp on the non-rich?). While the VIPs celebrated themselves at the dinner inside honoring real estate moneybags Alice and Tom Tisch, modern dance legend Yvonne Rainer, and the star architects of the $400 million new wing, my $250 tickets (courtesy of this magazine) confined me outside in the garden, with the after-partyers, a youngish “social” crowd such as you might find in a Sex and the City sequel to a sequel to a sequel, the Matisse and Maillol sculptures simply party decor for the open bars and selfies. The throbbing DJ drowned out any chat—or fruitful eavesdropping. It was a fund-raiser, after all: The modern masters were merely the mise-en-scène for the schmoozing and mingling rich, the human (all too human) life-support system for immortal Art. Inside, beyond a phalanx of greeters, the VIPs applauded one another, protected from scrutiny.

Where would toxic philanthropists be without the arts to stave off the pitchforks? They’d be simply toxic, which clarifies things. The expulsion from the Garden is a classic motif about the end of innocence. Like Adam and Eve, museums and artists now face a rude alarm bell. Will they reckon with their de facto role as toxic philanthropy’s enablers? Are we on the verge of a new global awakening? Take it from Carmela’s shrink: One thing you can’t say is nobody told you.