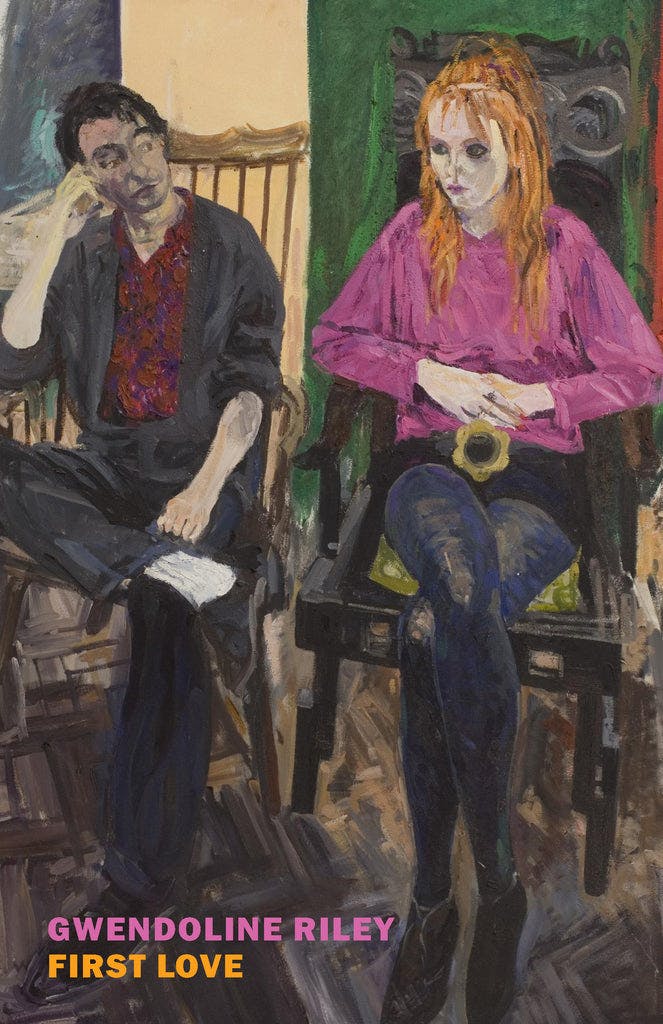

The narrator of Gwendoline Riley’s First Love lives with her husband, a state of affairs that neither husband nor wife can quite believe. Edwyn and Neve are “two people who’d always expected, planned, to live their lives alone.” When the novel opens, they have been living together for 18 months, in the London flat that Edwyn owns. Over the next 170 pages, Neve examines the events of this period, wondering at the difference between her life pre-Edwyn and the life they have now.

The publication of First Love in 2017 marked a turning point in Riley’s career as a writer. In the previous decade and a half, she had written four novels that were well-received in the United Kingdom, where she lives, but somehow remained under the radar, despite occasionally winning awards and receiving award nominations. (Only two of these novels have been published in the United States; both are now out of print here.) First Love won many more—and now, every time I open Twitter, there’s a Brit or an Anglophile announcing that they are reading Riley, with a level of excitement usually reserved for Sally Rooney or Elena Ferrante. Last month, New York Review Books published First Love alongside her most recent novel, My Phantoms, first published in the U.K. in 2021.

Like Rooney’s novels, both these works focus on fraught, complicated relationships. Rooney and other contemporary novelists like Patricia Lockwood and Ben Lerner offer interpersonal connection as an antidote to all manner of problems: to a troubled childhood or bad sex, to political crises or to the enervating effects of social media. Riley takes a different approach. Politics is almost entirely absent from her novels. It’s impossible to imagine her narrators on Twitter. More significantly, the relationships Riley writes about offer little refuge or redemption. They are sites of unproductive struggle, interesting not for what they might become but for how they repeatedly refuse to become anything other than what they are.

Riley’s novels are short—usually under 200 pages—and each one is narrated by a woman a few years further into adulthood than the last. (The narrator of her 2002 debut, Cold Water, is 20; the narrator of My Phantoms, like Riley herself, is in her early 40s.) These narrators are not the same person, but certain details come up again and again, if not invariably: divorced parents, a single sibling, a childhood spent in Liverpool and early adulthood in Manchester. The narrator is a writer or an academic, a vegetarian or a vegan. She drinks too much, or used to drink too much and now drinks (almost) nothing at all. She’s depressive, prickly, evasive.

She is also, in Riley’s first few novels, a drifter. She drifts between the cinemas, bars, bookshops, and cafés where she and her friends work or play gigs. She ends or half-ends things with men before drifting back into bed with them; she declines to pursue relationships that seem as if they might actually work. Nothing makes her abandon a friendship faster than a friend wanting to talk about feelings; she prefers trading wisecracks and reading the newspaper together. Riley’s second novel is called Sick Notes: Her early narrators are always trying to get out of something. In her two most recent novels, Riley has shifted to examine what it means to stick with someone—in First Love a husband, in My Phantoms a mother. These works offer a remarkable confrontation with what we can’t help knowing, but what fiction—so often about relations coming into being, evolving, even ending—rarely represents: that relationship dynamics are hard to change.

The marriage in First Love may be as surprising to readers of Riley’s previous novels as it is to Neve herself. Whereas Riley’s younger protagonists roved around and between cities in the north of England and made sudden dashes to the U.S., Neve has settled in London. (Riley denies us some of the conventional pleasures of fiction: how Neve and Edwyn met and got together.) Neve, a writer, works from home and mostly stays home after work too. “I like how things work down here, seeing people once a month, if that. Once every six months,” she says. “I’m very happy to spend my time with Edwyn. I love our evenings, our routines.”

Describing these routines, Riley captures the private half-language that develops between people in love. Neve is “‘little smelly puss’ before a bath, and ‘little cleany puss’ in my towel on the landing after one”; wearing dungarees, she’s “you little Herbert!” When Edwyn gets home from work, they cuddle and make “little noises—little comfort noises” (“prr prr”) in their throats. Other narrators might perform embarrassment in setting out such exchanges, but Neve’s cool tone shifts the embarrassment onto the reader: Even as she offers us these phrases, it feels as if we’re intruding.

There are, Neve admits, other ways their evenings unfold. She has married a cruel bully, one who finds elaborate ways to label her crass, immature, attention-seeking, selfish, sex-obsessed. Edwyn is some decades older than Neve and in ill-health. His pain and fear express themselves in bizarre, repetitive tirades that take Neve as both target and witness. These tirades often have a misogynistic flavor—“I have no plans to spend my life with a shrew.… A fishwife shrew with a face like a fucking arsehole that’s had … green acid shoved up it”—or invoke the class difference between them: “I know you hate anyone who didn’t grow up on benefits. I know you loathe anyone who didn’t grow up in filth, on benefits.” At other times he’s simply cold. Coming home from work one day shortly after Neve’s father has died, he is perplexed to find her crying. “I don’t understand,” he says. “You’re an intelligent woman. Did you imagine he was going to live forever?”

Why doesn’t Neve leave? For one thing, she thinks that Edwyn’s rages have become less frequent. Now she knows to avoid the things that trigger an attack or prolong one. She has learned to manage her own feelings too: She used to be scared by Edwyn’s attacks and by the “low, pleading sounds” she would hear herself make in response, but now she tells herself that “none of this was personal.” She can maintain a cultivated reasonableness in the face of her husband’s fury.

But there are more complicated reasons Neve stays with Edwyn. Her examination of their time together is interspersed with memories of earlier important figures in Neve’s life: her father, her mother, and a self-absorbed American musician named Michael. (All three will be familiar to readers of Riley’s earlier novels.) Her father was physically and verbally abusive. Like Edwyn, he had a particular taste for humiliating the women around him. Her mother is flighty and needy, qualities Neve is horrified to recognize in her former self, and in her behavior toward Michael. Marriage to Edwyn offers a strange escape from these qualities. If she doesn’t leave, she won’t fall back into the peripatetic life she had before they met, and that her twice-divorced mother has still. And since Edwyn is enraged by pleas for affection, Neve no longer makes them.

The novel’s final chapter consists almost entirely of dialogue: another, recent fight, this one particularly vicious, and distressing for Edwyn as well as for Neve. Neve raises the possibility of divorce, which Edwyn ignores. She asks for forgiveness for a long ago misdeed and Edwyn refuses (“I don’t forgive people,” he tells her). A stalemate, yet one in which both adversaries have expressed their feelings more honestly than usual. The next morning, husband and wife walk into town together. They stop to look at a crow and have an affectionate, teasing conversation about outfits that Edwyn wore as a child. It’s a carefully ambiguous ending: Is Neve merely humoring him? Is the relationship over—or have they reached an understanding that will change things for the better? Neve withholds her thoughts from us in these last pages, so we don’t know for sure. But each spouse gets something from the relationship as it is, from the fights as well as from the tenderness. Love for Riley is not, or is not only, patient and kind. If a marriage can solve one set of problems while creating another—well, perhaps that’s enough.

In My Phantoms, the

narrator has found a love that is patient and kind—and as

such, almost totally uninteresting to Riley. Bridget has been with the gentle,

supportive, generically-named John since she was 20. She’s an academic,

he’s a psychoanalyst, they spend their evenings together reading or watching foreign

films. In a novel full of conversation, we hear only one between Bridget and

John, about the book’s subject: Bridget’s mother, Helen. Riley’s other novels sometimes

feel cluttered with relatively minor characters. My Phantoms simplifies

its narrator’s adult life—one contented partnership, one job, no friends worth

mentioning—and as a result has a sharpness of focus

that makes it Riley’s most unsparing novel, and her best.

Helen is at once predictable and unknowable to her daughter. This is true of most parents and their children—but Helen, more than most, resists being known. She married Bridget’s (awful) father because “it was just what you did,” lived in the suburbs for decades because it was “normal” to do so, hated her job because “Everybody hates their job, Bridge. Everybody does.” She longs for attention but fears, under its light, doing or saying the wrong thing. (“What’s it to you?” she’ll say if Bridget asks about her life, or else simply put her arms over her head and stop speaking.) She loves to complain and is evidently unhappy, but responds to sympathy and advice alike with incomprehension, scorn, or denial. “I think she liked finding life a little bit crap,” Bridget reflects at one point.

In her first decade of adulthood, Bridget almost never sees her mother. But when Helen, who lives in Manchester, turns 60, she announces that she will be spending her “big birthday weekend” in London. This turns into an annual visit, with an annual agonizing mother-daughter birthday dinner. As Bridget recalls these dinners, and the accidents and illnesses that befall Helen as she enters early old age, My Phantoms shifts from a study of character to one of relationship. Bridget, as well as Helen, bears responsibility for the “stubbed-toe, short-leash” quality of their conversations. “I didn’t, as a rule, talk to her about anything that mattered to me,” she says. “Why upset her by talking about things she couldn’t understand or enjoy?” She refuses to let Helen meet John, despite her mother’s pleas and tears. And on the rare occasions where Helen does admit to feeling lonely or sad, Bridget responds with cheery rationalizations and deflections. Bridget knows full well that this performed jolliness, her insincere affirmations, are a kind of cruelty. But recognizing a pattern is not the same as being able to stop yourself repeating it.

If that seems fatalistic, My Phantoms ultimately offers a perspective more fatalistic still. When Bridget does break the pattern and share parts of her life with Helen—she sends her Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels for Christmas, suggests having Helen’s birthday dinner at a vegan café, eventually allows her to meet John—it invariably goes badly. In response to the Ferrante novels, Bridget receives a series of texts:

“I don’t know who anyone is! ☹”

“Is Lenu Lina or is Lena Lulu? Argh!”

“Still waiting for ‘Ferrante Fever’”

In one of the novel’s most prolonged, painful exchanges, Helen, with increasing distress, demands to know why she has never met John. Finally, Bridget gives in: “Do you want me to tell you why, Mum? Why I have to keep things separate?” Helen falls silent—and then scrabbles for the television remote and asks Bridget what she wants to watch. Reflexively or deliberately, Helen and Bridget collude in maintaining their distance from one another.

We read

novels—among other reasons—to recognize ourselves and our experiences in them,

and there can be few people who have no experience of relationships that are

enduringly boring, frustrating, or bewildering. Perhaps this explains why

Riley has found a wider readership with First Love and My Phantoms than with her earlier novels. But depicting the

minutiae of boring, frustrating relationships poses a challenge for writers—no

one wants to be bored and frustrated while reading. Riley’s novels, consisting

mainly of dialogue, work a kind of magic: Edwyn’s unhinged rants and Helen’s

verbal tics and long, repetitive accounts of being slighted or overlooked are at

once believably maddening and oddly addictive. Having to listen to these monologues

would be unbearable, and yet to read them—to witness their absurdity without being

their audience—offers a perverse pleasure.

My Phantoms ends with Helen’s death, and with the sense that death was the only possible way out of mother and daughter’s rigid choreography. Returning to First Love having read My Phantoms, one imagines the same will be true for Neve and Edwyn. In Riley’s novels, relationships with spouses and parents are intractable: two people endlessly talking past one another, ignoring or refusing the possibility of authentic connection. Such relationships may not be “worth it” by any reasonable calculation, but that doesn’t mean we turn our backs on them. They’re what we have and what we’re stuck with—and then they’re gone.