The Swedish Academy, which awards the Nobel Prize in literature, is fond of overthinking things—perhaps unsurprising, given that it is made up predominantly of Nordic academics and other members of the ponderousoisie. This is, after all, an award that is famous for having been won by Sully Prudhomme, Carl Friedrich Georg Spitteler, and Dario Fo—and never having been won by James Joyce, Marcel Proust, or Leo Tolstoy, among others. Recent selections have suggested not only a continued devotion to snubbing stars and rewarding obscurities but a highbrow form of trolling.

The decision to award the Nobel to Bob Dylan—who you might recall is a songwriter and musician and not an author (though he has written one very good memoir, one atrociously bad book of poetry, and one forthcoming discourse on The Eagles’ “Witchy Woman” and 65 other songs)—kicked off what could be described as the Nobel Prize’s chaos era. A year later, Kazuo Ishiguro, one of the most popular writers of literary fiction on the planet, won the Nobel. A year after that, the Nobel was canceled amid a horrific #MeToo scandal that led to several resignations—and a conservative backlash—within the Academy.

When it returned in 2019, the Nobel Prize promised a host of changes, among them a commitment to finally start looking beyond its typical remit—continental Europe and the United States—for laureates. It then promptly awarded the Nobel to two Europeans—including Peter Handke, an Austrian novelist of unimpeachable literary merit who also gave a eulogy at Slobodan Milošović’s funeral. Last year, it recognized the Zanzibarian British novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah, an obscure figure even by the Academy’s own standards: His books had sold, in total, 3,000 copies in the U.S. before he was recognized. Gurnah was, moreover, most famous for his critical work on several figures who are regularly touted as potential winners, most notably Africa’s most influential living novelist, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. The general portrait was one of unrest, even an identity crisis: the Swedish Academy awarding new modes (Svetlana Alexievich’s oral histories, Dylan’s songs about wiggling), thumbing its nose at critics, and manically shifting gears.

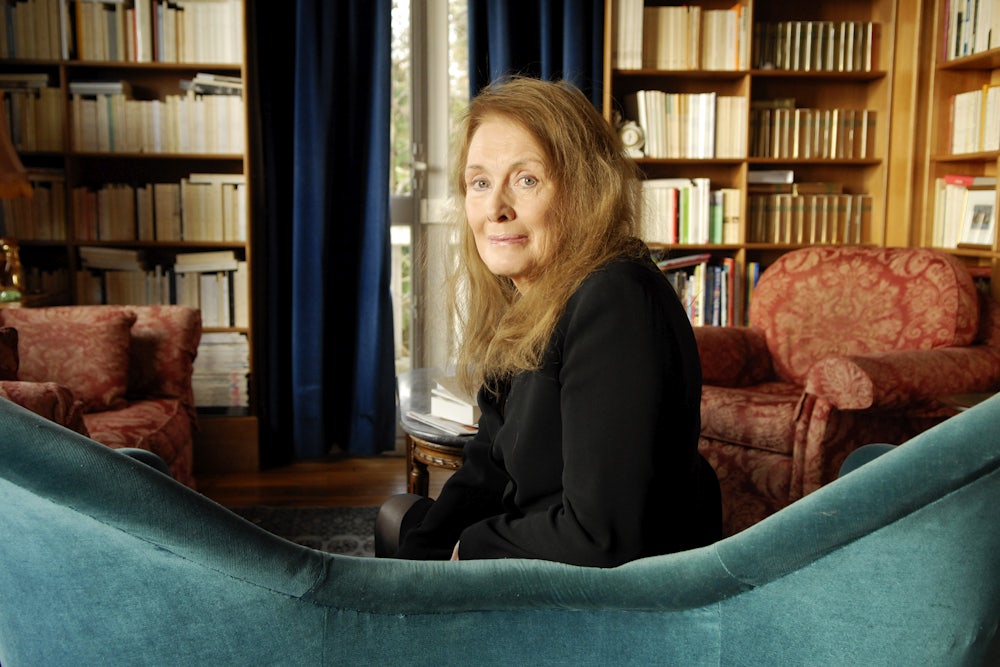

All of which makes the Swedish Academy’s decision to award the Nobel Prize in literature to Annie Ernaux on Thursday so surprisingly and blessedly straightforward. Ernaux is arguably France’s greatest living writer and an eminently deserving laureate. The speculation leading into Thursday’s announcement was that the Swedish Academy would likely select a writer from a list of luminaries—a group that included the likes of Mario Vargas Llosa, Günter Grass, Tomas Tranströmer, J.M. Coetzee, and more recently, Handke. “In my view, they have a laundry list of ‘great authors’ that have been around for decades,” the journalist and novelist Jens Liljestrand told me before the announcement. “Now they mix these names with ‘new’ names—like Glück, Tokarczuk, and Gurnah. So that would mean we go back to greatness this year.” Liljestrand was right. Two minutes after the announcement, I received a D.M. from him: “Told you: laundry list.”

Ernaux’s books—both memoir and lightly fictionalized autobiography—are among the most vital works of literature produced in the last half-century. They catalog, in intimate and striking detail, Ernaux’s life and times. They are often political but always in a deeply personal way: Ernaux renders the events of her life, whether they are growing up impoverished in rural Normandy, having a back-alley abortion as a 23-year-old student, or having an obsessive affair with a diplomat, in language that is clear-eyed and direct. She is, in many ways, a pioneer of what is now called “autofiction,” but she still stands out as a singular writer in global literature. The Years, her masterpiece, is a revolutionary book, one that tells the story of a generation of French women—and indeed, often slips into the third person—through Ernaux’s own experiences. But her works are best experienced as a single expression, of Ernaux focusing on certain aspects of her life and experience.

“Annie is a feminist, but even more than that she goes even further: She described without apology the experience of women,” Ernaux’s American publisher, Seven Stories’ Daniel Simon told me. “Annie is a kind of universal figure. She’s a very French writer in a certain sense, but not in the way that we’re used to—she writes very direct sentences. Annie always stuck to her guns, to her project, whether other people understood it or not, and has done so for more than 50 years.”

“This kind of dedication to a project—rather than writing for an audience—that’s such a triumph for writers and a way for a commodification, away from a consumerist and market-based approach,” Simon continued. “Frankly, that’s so important. Writing is her life. Writing is life, to her. It’s very different from someone who has writing as a career.” Even though Ernaux had been a perennial front-runner, Simon didn’t expect her to win; to his mind the Nobel Prize Committee would never “choose someone who does sex so viscerally the way that Annie does.”

“It’s just uncomfortable,” he said. “They want a veil or a triple veil. Yes, people have sex, but they don’t want to know that much about it.”

Ernaux’s victory has already been interpreted as a political statement in the U.S., given her writing about the horrors of back-alley abortions in France. Anders Olsson, who chairs the Nobel Prize Committee, pushed back against this reading when asked about it shortly after the announcement. “We concentrate on literature and literary quality, and we don’t have any more message to the world,” he said. “But it’s very important for us also that the laureate has a universal consequence in her work—that it can reach everyone. In that respect, the message is: This is literature for everyone.”

He is right in the larger sense: Ernaux is not being awarded as a coded political statement about Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health. But the Swedish Academy knows what it’s doing, and a message about reproductive rights is certainly knit up in Ernaux’s victory. It is just a part of it, though: Olsson and his fellow Swedes are making a statement about Ernaux’s literary merit first and about American politics somewhere else.

In the larger world of the Nobel Prize, there is a sense that the Academy is continuing to correct its past wrongs. Asked in the press conference about the decision to award a French writer for the sixteenth time, Olsson pointed out that they had awarded one from Africa a year earlier—though Gurnah has been living in the U.K. since he was a teenager—while noting that Ernaux was a woman. (She is only the sixteenth woman to win the Nobel, which has been given out since 1901.) The general sense is that the Nobel Prize will continue to address some of its past ills—the lack of representation from women and writers from Africa and Asia—but only sparingly. This version of the Committee is bent on stubbornly doing whatever it pleases. But none of that matters until the frenzy of speculation once again descends in earnest again next autumn. For now, the Nobel Prize has gone to someone who is clearly deserving of the accolade.