One of my first memories of the publishing industry is the story of a friend who was asked to provide an author photo to help sell the international rights to her debut novel. My friend is not a person who thinks particularly of her looks—she has always focused on her writing. She submitted a photo of herself standing in a doorway wearing a winter coat. The Italian rights sold, the French did not. Her agent, also a woman and a veteran of the industry, joked that perhaps the French would have gone for the rights if the photo had been more revealing. “The lesson I took,” my friend told me, “was that I was being vetted for physical attractiveness”—not the value of her novel.

The author photo is something writers agonize about. Should you smile? Should you seem remote or accessible? Should you lose weight? It is the prelude to the public life of a book: the tours, readings, interviews, and media appearances a writer hopes to undertake on her publishing journey. A writer spends so much of her time subordinating her personal life to write fiction, and then suddenly, on publication, the personal life is all that matters. I recently listened to an interviewer ask a very famous author about a scene in her new novel, how it surely resembled the recent death of her father. As the author began to answer in earnest, I turned the radio off. I couldn’t bear to hear it.

The bar for every writer of fiction is that the novel is an invented thing. And yet each time we write, novelists are treated like spiritualists who rip off the grief-stricken—as though our inventions are some sort of hustle. Surely you must have some experience like this: Tell us about it. On tour for my first novel, a reader asked, “How much of this is autobiographical?” I replied, nearly snarling, “If you knew, would you believe it more or less?”

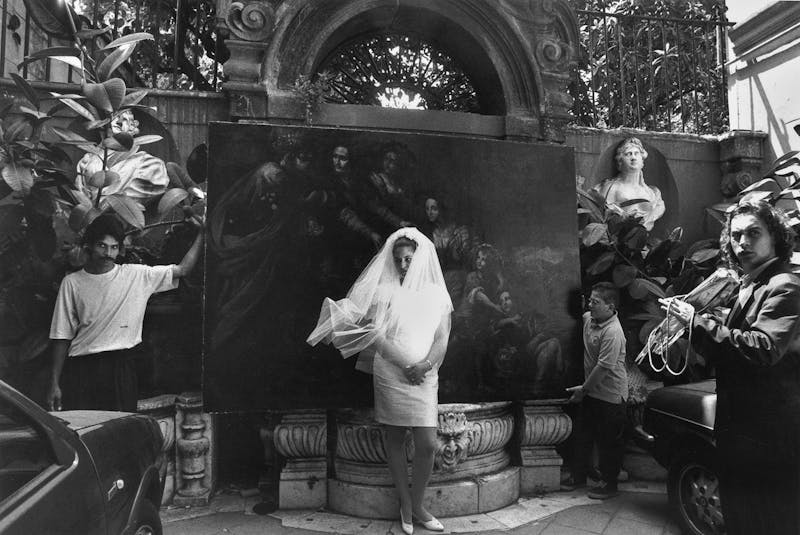

Elena Ferrante wanted none of this. Her career as a writer—now in its third decade—is anonymous, her name a pseudonym, her face unknown. “Elena Ferrante was born in Naples,” reads the author bio on the inside flap of her internationally bestselling novels. The only word readers can reliably identify any part of her work with is Naples. There is no author photo. Since her 1992 debut,Troubling Love, was published in Italy, Ferrante has rebuffed in-person interviews, bookstore readings, lectures, television appearances, award banquets—anything, really, known to sell a book these days. She has communicated through her publishers for more than 24 years, during which she has published seven books. Her last four are considered a single novel, her masterpiece—The Neapolitan Quartet—an unparalleled examination of a friendship between two women in Naples: their marriages, pregnancies, ambitions, jealousies, rivalries, and loves, as well as the past 60 years of Italian history. Despite her refusal to appear in public, the books have sold 1.2 million copies in the United States since they were first published in English in 2012.

In Ferrante’s novels, women disappear quite often—either at the hands of others or by their own will. Disappearance is a way to fight back against the demand that, as women, they must forgo any right to their humanity in service to their families. It is an act of rebellion against the idea of what women should be—an idea usually determined by men. Ferrante’s characters are similar in the way sisters, or women of the same family, are similar: the abandoned wife, the drowned woman, the daughter who imagines she will not meet the fate of her mother, the mother who longs to throw off the yoke of the child.

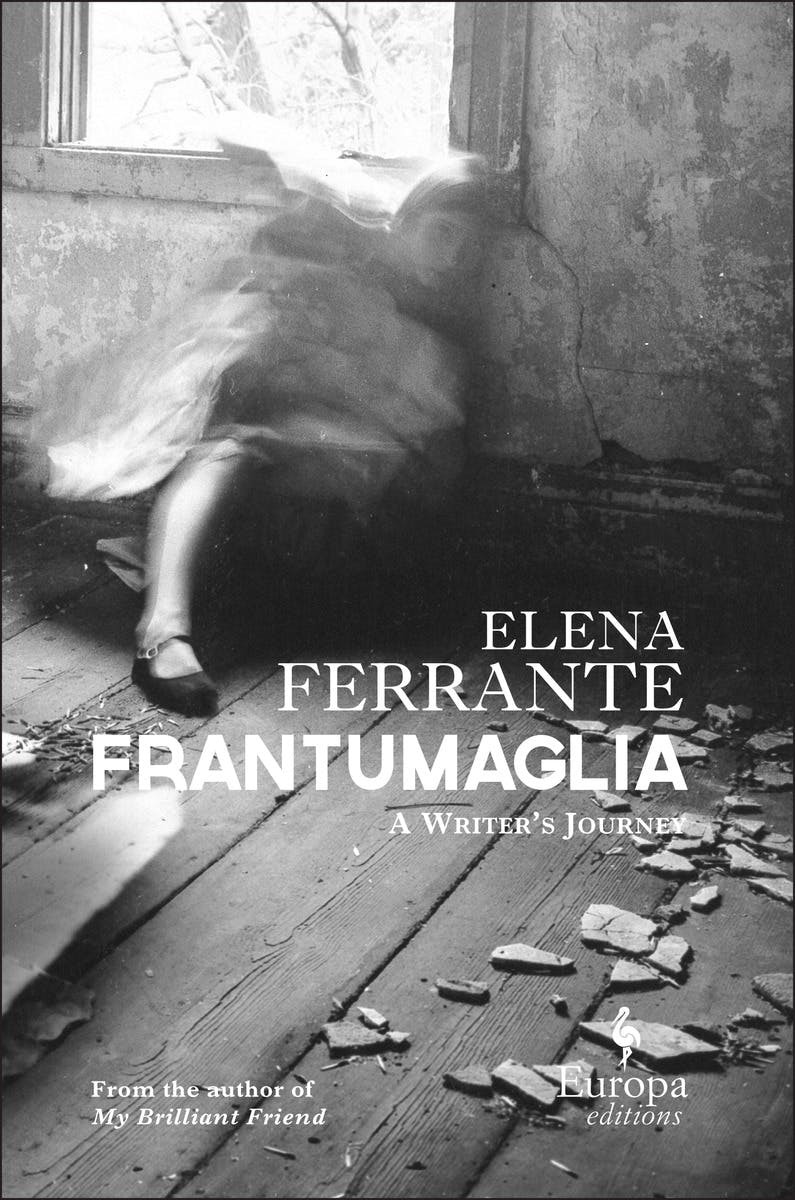

Ferrante’s latest book to be published in English, Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey, is also about a woman’s disappearance—her own. In it, Ferrante records her 24-year fight against the manipulation of her authorial identity. Just before finished copies of the book were sent to reviewers, the Italian journalist Claudio Gatti announced that he had proof of Ferrante’s “real” identity. After scrutinizing financial records and real estate transactions, Gatti said, he had identified Ferrante as Anita Raja, a literary translator who works for Ferrante’s Italian publisher, Edizioni E/O. The New York Review of Books announced the news in a blog post at one o’clock in the morning—the late hour due to its simultaneous publication in the French, German, and Italian presses—as if Gatti had caught a spy.

In Italy, the news was received with a shrug: The naming of a Ferrante suspect had become such a common occurrence, it seemed as though everyone in Italy might take a turn. But readers in the rest of the world denounced Gatti’s actions as a violent unmasking. In The Times Literary Supplement, Frances Wilson condemned it as a “catastrophic misunderstanding of what criticism is or how reading actually works.” Gatti, Wilson said, had actually done readers a disservice: “No one,” she insisted, “really wanted to know the identity of Elena Ferrante.”

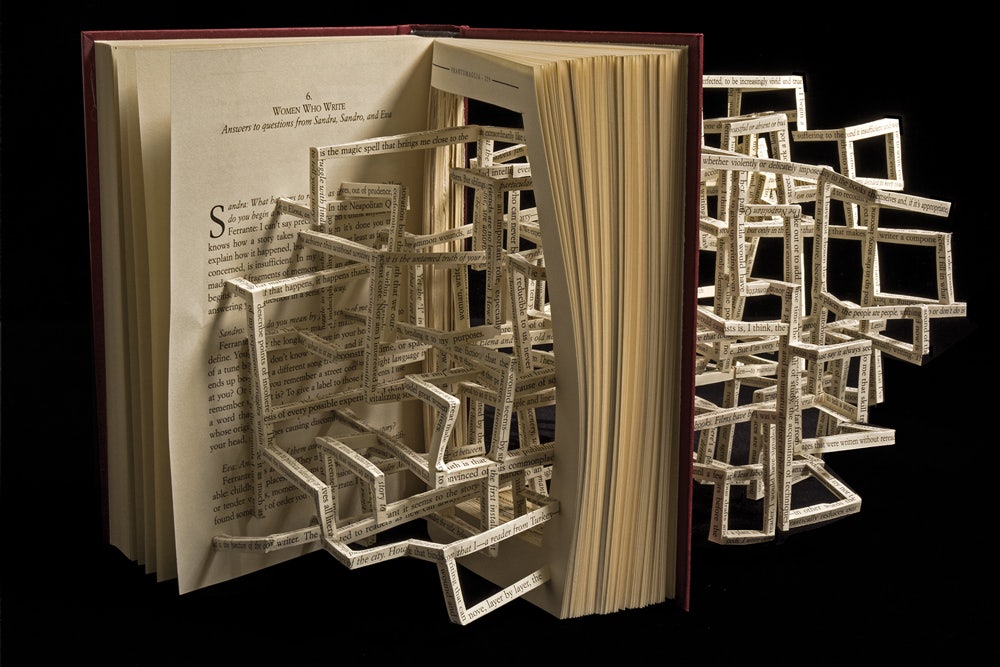

In Frantumaglia, Ferrante seems to anticipate her own discovery: The book is like a mask hidden beneath a mask, ready to be displayed when the first one is torn off. Organized with the care of an Italian archaeological museum, it is not meant as an introduction to Ferrante’s work—she even calls it an afterword. Frantumaglia is Ferrante for the Ferranteans, her readers who have long enjoyed the puzzle over her work and her self without ever needing it solved. The reader is meant to enter through her novels, then dive deeper here, into this mix of letters to fans, imagined conversations, interviews with the press, essays—there is even a short story—and come out the other side with no clear answers, only more questions.

Frantumaglia resists any narrative or forward motion. As an unreliable and at times unsympathetic narrator, Ferrante constantly interrupts herself with addenda, footnotes, and postscripts. The book is not a diary, a memoir, or an autobiography. Rather, the fragmentary nature aids Ferrante’s hiding of herself, and like any fragmented narrative it describes something that could not be described if the parts were whole. Through this diffraction, we see what Elena Ferrante wants us to see: A portrait, elided and mercurial, that she asks us to believe is her.

“My mother left me a word in her dialect that she used to describe how she felt when she was racked by contradictory sensations that were tearing her apart. She said that inside her she had a frantumaglia, a jumble of fragments.” Ferrante explains the curious title of her work in an autobiographical essay near the beginning of the book, one of the few glimpses she gives her readers of her childhood, and of her mother—a woman who springs instantly to life, like the mothers in many of her novels. “The frantumaglia . . . depressed her. Sometimes it made her dizzy, sometimes it made her mouth taste like iron. It was the word for a disquiet not otherwise definable, it referred to a miscellaneous crowd of things in her head, debris in a muddy water of the brain.” A few sentences later, we arrive at Ferrante’s own sense of the word:

It’s also the right word for what I’m convinced I saw as a child—or, anyway, during that time invented by adults that we call childhood—shortly before language entered me and instilled speech: a bright-colored explosion of sounds, thousands and thousands of butterflies with sonorous wings.

Childhood is a theme Ferrante returns to again and again in her novels—she identifies intensely with the way a child grapples with words, how children shape and create their selves in a slow accumulation of thoughts, words, and experiences. This vision of her interior, and the sense of how it came from her mother’s interior, is some of her most beautiful writing, consistent with her sense of inheritance from the past. It’s a glimpse into a life not unlike the one we might have imagined for her, consistent with the world of her novels, and deeply satisfying to those readers who would know her.

In another fragment, an interview in the Italian newspaper L’Unita, Ferrante is asked whether her novels originated as private writing, which she vigorously rebuffs. “I write so that my books will be read,” she insists. One of the most startling illusions with Ferrante, novel to novel, is the sense of being admitted to the deeply private thoughts of her narrators—it is part of why her fans love her. But for women, private writing can be considered noncanonical behavior—silly, tragic, self-indulgent. Ferrante is not a diarist, and her stated desire to remove herself from that kind of condescension is one of Frantumaglia’s openly stated themes.

The book is divided into three sections. In the first section, entitled “Papers: 1991–2003,” Ferrante is still in the first flush of her career, the sort of idealist you would meet in an introductory writing class who believes she is a pure artist, and is obsessed with the pleasures of the written word. She opens Frantumaglia with the document that is now ground zero to her pseudonymous legacy, a letter to her editor refusing all publicity, refusing any appearances of any kind, agreeing only to do a few interviews, and only in writing: “I am absolutely committed in this sense to myself and my family. I hope not to be forced to change my mind.”

In the second section, “Tesserae: 2003–2007,” Ferrante is past her first two novels, and has begun to settle into her own story. In an interview from 2003, she is more placid and professorial, and gives many details about herself. She describes herself as having a degree in classical literature, and states that she works as a scholar, translator, and teacher. She admits to having lived in Greece for some time, as rumored, but says she has returned to Italy and remains entirely Neapolitan, “in my gestures, my words, my voice, even when I put an ocean between us.” When the interviewer asks why she believes nothing in an author’s personal history is useful to better understanding the author’s work, she gives one of her best replies:

I think that, in art, the life that counts is the life that remains miraculously alive in the works.. . . Neither the color of Leopardi’s socks nor even his conflict with the father figure helps us understand the power of his poems. The biographical path does not lead to the genius of a work; it’s only a micro-story on the side.

But the interviewer still hounds Ferrante about her “true” identity, as if he might catch her in a written interview. In the process, he fails to ask her even a single question about her novels. In a 2006 interview, he suggests that “the problems of your identity often overshadow the literary questions,” and asks how she can prevent that. Her answer shows her disappointment.

You ask me how to keep people from talking only about who I am, and neglecting the books. . .. Certainly you—forgive me—aren’t doing anything to reverse the situation and confront what you call the literary questions.

The events of Ferrante’s life are in the background of all of her interviews, visible only if she is asked about them. A decade ago, the Italian press published a series of pieces asserting that she was a man, and interviewers began to ask whether she recognized something “non-female” in her writing. “I’m afraid I learned to write by reading mainly works by men and constantly redoing them,” she responds. “It took time for me to learn to love women writers.” She had earlier referred to these allusions in a more sidelong, provocative way: “I’ve believed, angrily, bitterly, that men who are masters of writing are able to have their female characters say what women truly think and say and live but do not dare write.”

By now, Ferrante has learned to take the media’s attempt at gossip and turn it back to the work. Her continued withdrawal is a refusal to be consumed by all the duties of a woman in public—to seize instead what she sees as this masculine power to write what women truly think and live and do not dare write. This sets her apart from other pseudonymous women writers of the past, who often hid behind male names in order to get published. Elena Ferrante has established the boundaries of a complicated creative space that she is determined to protect at all cost.

“Letters: 2011–2016,” the final section of Frantumaglia, gives us Ferrante as best-selling author—cagey, bored, at times terse, at times expansive. In her Paris Review interview, she entirely avoids the “who are you?” question, and instead focuses richly on her work. Many of these recent interviews are a pleasure to read—Ferrante’s professorial side is less didactic, more relaxed. But when asked, “Will you tell us who you are?” she answers: “Elena Ferrante. I’ve published six novels in 20 years. Isn’t that sufficient?” At this point, I have to agree. Why aren’t the novels enough?

But for all of her explanations on the topic of her withdrawal, the press appears, in these pages, determined to misunderstand her. If she seems repetitive at times, she is—but only because the questions are. Soon, she begins to sound like someone pleading for her life. At one point, she vows to stop publishing if she is exposed. And when she is asked to consider the legacy of her absence, she points a finger home:

Those who became aware of the books later . . . as a result of the media attention, at least here in Italy, encounter them with an initial distrust, if not hostility, as if my absence were an offensive or culpable type of behavior. . .. The only thing I can do is continue my small battle to put the work at the center.

The final conversation in Frantumaglia is conducted amid difficult straits: Both Ferrante and her interviewer are up for one of Italy’s top literary prizes. What remains unmentioned is that there were protests from the jury about Ferrante’s anonymity, as if she might be stealing the prize if she were to win—she was even accused of being a virtual competitor. La Repubblica, which fought the hardest for her to reveal herself, ran a campaign to support her inclusion. But as an editor there, Antonello Guerrera, explained to me, her decades of refusals had taken a toll. “Many in the literary world in Italy,” he told me, “never forgave her anonymity.”

To anticipate her name was to anticipate a certain disappointment. In n+1 last year, Dayna Tortorici satirized the American speculation of a Ferrante unmasking:

Whenever I hear someone speculate about the true identity of Elena Ferrante . . . a private joke unspools in my head . . . She’s Lidia Neri. She’s Pia Ciccione. She’s Francesca Pelligrina. Domenica Augello. Different names every time, but the reaction is the same: a momentary light in the listener’s eyes that fades to bored disappointment. An Italian woman from Naples, whose name you wouldn’t know. Who did you expect?

And now, according to Claudio Gatti, she’s Anita Raja. To find her, Gatti followed the money: How else, he asked, could a literary translator like Raja have afforded a “2,500 square foot, eleven-room apartment on the top floor of an elegant prewar building in one of the most beautiful streets of Rome . . . with a value estimated between $1.5 and $2 million”? Raja and her husband, Domenico Starnone, have both previously been identified as Ferrante, and both have denied it.

It was an astonishing feat—not Gatti’s dig through public records, but that an esteemed literary review conspired in what can be seen as an act of violence against the imaginative country of a major author, the one act she has said would result in her ending her career. Hugh Eakin, The New York Review of Books editor who worked with Gatti, defended the choice to The New York Times. “Now that an expanded version is about to be published in English,” he said, “it seemed there was a legitimate occasion to inquire about the relation between the book and its author.” Was her crime, then, merely to publish Frantumaglia in English?

Frantumaglia is a book created in the spirit of an author’s legacy, less a memoir than a memento mori. As I read it, I was reminded of the intense pruning J.D. Salinger did of his own work, blocking publication of his uncollected stories—which included imperfections that would have worn down his legacy. But as I continued, Frantumaglia began to seem more like Vladimir Nabokov’s Strong Opinions, his collection of his interviews and op-eds, where he even edited the questions as well as his answers. These authors were fanatically in control of their bodies of work and their biographies, with good reason: They formed an essential extension of their selves. Ferrante even experiences this as self-care: “In my experience, the difficulty-pleasure of writing touches every point of the body,” she writes in Frantumaglia. “When you’ve finished the book, it’s as if your innermost self had been ransacked, and all you want is to regain distance, return to being whole.”

Gatti has also defended himself against the outcry over his exposé. “Why should lying by best-selling authors to readers who love their work and have a legitimate interest in knowing who the authors are [be allowed]” he insists, “when you don’t allow politicians to lie to their voters?” And yet few readers, if any, have found any value in the knowledge of Gatti’s accusation, including Gatti himself. Despite his claim that he exposed her to help us interpret the novels, he concedes, “There are no traces of Anita Raja’s personal history in Elena Ferrante’s fiction.”

Raja was born in Naples, the daughter of a German immigrant, but her family moved to Rome when she was three. Her ancestors were not among the Neapolitan poor of postwar Italy, but rather experienced Polish pogroms and Nazi persecution. If Ferrante is Raja, and the Ferrante who spent the majority of her life in Naples—the city she has said she feels “in my gestures, my words, my voice, even when I put an ocean between us”—is also an invention, it would mean Frantumaglia is a metafiction, her most experimental text yet, a massive prank on criticism and the media: all of it done to show us how badly we read what we read, how badly women writers are treated, and how badly the press operates. It would mean her mother’s frantumaglia was not verifiably her mother’s; her childhood impressions the impressions of a fictitious child, not necessarily herself. That everything pointing us to some glimpse of her life was just a misdirection, so that the real woman behind Ferrante could remain hidden—and, one day, teach us that it never mattered who she was or where she was from.

As a reader, I never once grudged Ferrante her space—perhaps because, as a writer, I understood it. I typically write best when I feel hidden and anonymous, as though anything could be possible. It was always clear to me that Ferrante’s battle against notoriety was waged, in a sense, for all of us. She wasn’t doing this just for herself—she wants to change the world.

Perhaps Ferrante will treat the “unmasking” as if it never happened. Or perhaps she will move on—a new persona, a new debut, a new audience, a new test of her insistence that only the work matters. We would have no way of knowing Ferrante’s new name. I think she would want it that way.

Near the end of Frantumaglia, Ferrante is asked what battles feminism still has to win. Her answer is revealing:

We vacillate between rooted adherence to male expectations and new ways of being female. Instead, we must fight, so as to bring about change that is profound. This will be possible only if we build a grand female tradition that men are forced to measure themselves against.

The answer suggests her relationship to her own identity, but also to the world. Only when the freedoms she imagines for herself in private are available to all women, she seems to say, can she herself be truly known. In Frantumaglia, Ferrante asserts the most fundamental and important truth of who she is: that she is someone who will do only as she will, and nothing else. That is what is at stake for all women. And the stakes, as Ferrante knows, have never been higher.