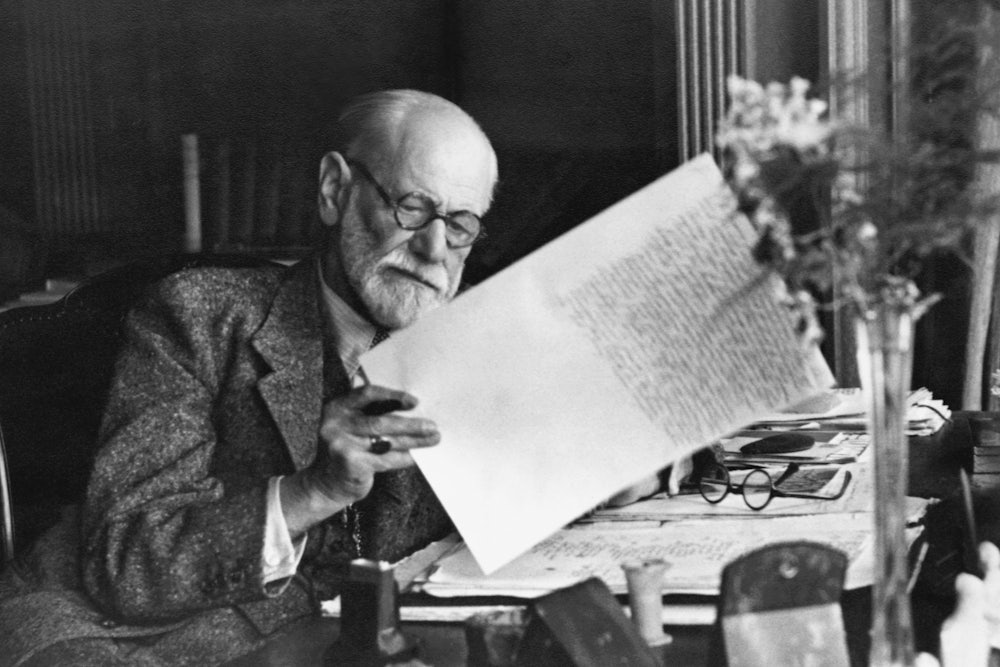

Sigmund Freud was an ambivalent man, especially when it came to politics. He often held conflicting views of political ideologies: For example, he expressed sympathies for socialism (“anyone who has tasted the miseries of poverty,” he wrote, can understand why fighting “against the inequality of wealth” was necessary), only to reject it elsewhere as antithetical to human nature. He similarly supported Zionism (even serving on the founding board of the Hebrew University) while simultaneously criticizing it as “baseless fanaticism.” Few works embodied this ambivalence better than Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), Freud’s most all-encompassing reflection on social matters. Discussing everything from religion to technology to bodily odors, he provocatively concluded that life in society is destined to be tragic: Whatever people gain from their social web, from safety to a sense of belonging, always comes at the price of unhappiness. Even his hair-raising escape from the Nazis, who in 1938 occupied Freud’s home country of Austria, evoked mixed feelings. “The triumphant feeling of liberation,” he wrote in a letter from exile, “is mingled too strongly with mourning for one had loved the prison from which one has been released.”

Civilization and Its Discontents became an instant classic, and over the decades, a wide range of readers—from Marxists and feminists to Christian conservatives—have debated Freud’s lessons for their own times. We now have an opportunity to do so for our own catastrophe-stricken world: In a new edition from Norton, the historian Samuel Moyn offers a new introduction, helpful notations, and a selection of short texts that explore the various ways that artists, philosophers, and social theorists have interpreted the book over the years. Moyn, who is also a frequent commentator on contemporary affairs, claims that while Freud’s environment in interwar Vienna may be different from ours, his ideas are still invaluable. They urge us to recognize the complicated relationship between psychology and politics, particularly how our arguments about economics, power, and social hierarchies are always shaped by our unconscious impulses. For Moyn, Freud’s approach is indispensable in the effort to tackle the most pressing dilemmas in contemporary society. It is only by understanding the psychological forces that foster oppression and conflict that we can hope to “make progress” and change our “war-torn and unequal world.”

It is tempting to harness Civilization and Its Discontents as a guide to our contemporary political morass, but doing so may obscure its most valuable message. While Freud does help us to better understand the entanglement of politics and psychologies, we can also read him as making an even more unsettling and relevant claim, one that goes far beyond politics: that human life is always dominated by ambiguity, uncertainty, and inconsistency, and that there’s no escape from the haunting torment that this entails. Even Freud’s unique writing style radiates with ambivalence. Instead of making arguments in an orderly progression, the book repeatedly digresses, openly questions its own assumptions, and flat-out contradicts itself. Civilization and Its Discontents is worth revisiting, not to make sense of our contemporary politics but because it captures our growing, and often overwhelming, sense of disorientation—over the pandemic, climate change, or other unprecedented crises—and explains why it is likely never to go away.

When Freud embarked on his quest to map the human psyche with The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), his focus was mostly on the individual. If people suffered from mental difficulties like hysteria, so the argument went, this was likely due to repressed personal trauma, which psychologists could expose and heal through one-on-one conversations. As time passed, however, Freud increasingly wondered what his new “science” of psychoanalysis meant for broader social questions. After the violence of World War I and the upheavals that followed, it seemed evident that people’s psychology was tied to collective causes: Their hopes and anxieties, happiness and despair, were inseparable from their thinking about religion, politics, or economics. With Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud therefore set out to explore how civilization—by which he meant the laws and informal norms that society imposed on its members, as well as the culture and technologies it produced—both reflected and shaped the human psyche. Could social structure help ameliorate common psychological miseries? Or was civilization responsible for them?

According to Freud, the restlessness that seemed to possess humans was endemic to life in society. It was the product of a paradox: The very rules and institutions that kept society together and secured human existence made people unhappy. In Freud’s formulation, life in a community required the repression of people’s urges. It in particular necessitated the subjugation of humans’ most powerful forces: the desire for sexual satisfaction (which Freud called Eros, after the Greek god of love) and for destruction (called Thanatos, the mythical personification of death). Because the alternative was chaos, society spent most of its energy policing its members, outlawing certain actions, and harshly punishing transgressors. Freud claimed that civilization emerged in a prehistorical event, when a group of brothers killed their father because they resented his mastery over the women of their tribe. They were then overridden by guilt, which led them to declare both murder and incest as taboo. Civilization, that is, was not the product of a conscious contract. It was premised on the denial of primal desires, which continued to boil under people’s thin crust of rationality and kept them forever disgruntled.

These ideas can read like wild speculation—Freud had no evidence for his origin story—but their purpose was to offer a sobering view of modern times. In Freud’s mind, twentieth-century Europeans may have thought of themselves as the paragons of progress, but they were not so far removed from their prehistoric precursors. Sure, they lived in greater comfort, but they, too, had to relentlessly repress their desires to navigate the demands of society. If anything, Western culture had reached a “high water mark” in the history of social prohibitions, especially in the sphere of sexuality, where it stigmatized anything beyond heterosexual monogamy. Its pressures were so intense that it led people to internalize its taboos, becoming too ashamed to recognize their true desires. In Freud’s eyes, the brutality of this coercion was akin to military occupation. “Civilization,” he wrote, “obtains mastery over the individual’s dangerous desire … by setting up an agency within him to watch over it, like a garrison in a conquered city.” Freud conceded that society does provide its members with some outlets to express their desires, sublimating them into art, sports, or science. But those were consolation prizes; by denying people their sexual and aggressive urges—a denial that was necessary for survival—society always inflicted misery.

Freud thus concluded that human existence was decisively tragic. Whatever gifts civilization bestows (say, better transportation or communication technologies) are also a source of sorrow (traveling sparks worry about loved ones; having to respond to frequent messages is a cause of stress). Moreover, this paradox of civilization meant that no social system, no matter how benevolent or enlightened, could make people happy. This is why, in a famous passage, Freud scoffed at the Communists’ promise to end social strife as “an untenable illusion.” Even if private property disappeared and people entered an era of complete sexual freedom (as a few Communists advocated), “the indestructible feature of human nature” meant that misery would manifest itself in new ways. The most people could hope for was to understand the sources of their despair and, in the process, make it more bearable. As he asserted elsewhere, this was the promise of psychoanalysis: It could transform “hysterical misery into common unhappiness.”

As Moyn notes in the new edition, Freud’s ideas sent shock waves through the world of social theory. The claims of Civilization and Its Discontents were so sweeping, and their implications so far-reaching, that thinkers spent decades responding to and adapting them. In his comments and in his selection of texts, Moyn highlights the clash between Freud’s Marxist fans and their centrist liberal opponents. Raging through the Cold War, this clash revolved around capitalism’s role in shaping our desires and the possibility of overcoming social hierarchies.

Despite Freud’s skepticism about the prospect of ending economic inequality, several Marxists believed that his ideas had important emancipatory potential. It was true, they claimed, that unhappiness stemmed from the social repression of our urges, but this was not an inherent feature of civilization; the blame lay with capitalism, with its obsessive imposition of work and unrelenting competition. For Wilhelm Reich, for example, who was one of Freud’s disciples and a Communist doctor, the endless hours workers spent in factories required an aggressive repression of sexuality. This was why workers sympathized with fascism, even as it went against their economic interests: The right provided a violent outlet to compensate for self-denial. During the Cold War, social theorist Herbert Marcuse popularized this line of thought, criticizing Freud for overlooking capitalism’s uniquely oppressive features. In Eros and Civilization (1955), which later became an important text for the New Left, Marcuse optimistically claimed that with some tweaks, Freud’s ideas could help reform the evils of capitalism (for example, by encouraging a less work-centered life) and bring about “a non-repressive civilization.”

On the other side stood Cold War liberals, who similarly understood politics in psychological terms. For them, however, the goal was defending capitalist democracy against the “emotional” outbursts that they associated with political radicalism. For figures like cultural critic Lionel Trilling, who spent much ink analyzing Civilization and Its Discontents, only the so-called “free world” managed to strike a balance between society’s demands and individuals’ irrational impulses. By limiting state oversight and maximizing people’s freedom, it reduced fracture and human unhappiness, all while recognizing that eliminating them completely was impossible.

From this perspective, Freud powerfully explained why challenges to existing social hierarchies, and especially the challenge from socialism, were dangerous. They were the expression of an infantile mindset, pointless efforts to transcend the limits of human existence, and their inevitable failure was bound to breed ever-increasing repression. Cold War liberals therefore claimed that Freud’s pessimistic embrace of unhappiness was capitalist democracy’s best defense against its reckless opponents. As Trilling said admiringly in his Sincerity and Authenticity (1972), Freud was a modern-day Job, who “propounds and accepts the mystery and naturalness … of suffering” out of understanding that the alternatives were much worse.

For Moyn, the debate between Marxists and liberals is central to Freud’s legacy because it can help us go beyond the laziness of our era’s social commentary. Freud’s focus on chaos and irrationality, which both Marcuse and Trilling shared, could be the antidote to certain centrist liberals’ superficial infatuation with science and enlightened technocracy as the solutions to our problems. Unlike Steven Pinker or Cass Sunstein (who, while unnamed, are alluded to in Moyn’s introduction), Freud and his followers did not try to brush away the conflict between desires and society. Instead, they debated how those conflicts could be best managed: for Marxists, by remaking economic and work conditions; for liberals, by lowering one’s expectations. This, Moyn claims, should be the starting point of any serious social thinking. Civilization and Its Discontents is a reminder that relating “psychic” well-being “to political health” is one of the greatest questions with which we should be grappling.

One can quibble with Moyn’s focus on the Marxist/liberal centrist debate, especially because it overlooks Freud’s significance for other equally important issues. The Norton edition, for example, says very little on the fiery disputes between Christian conservatives and feminists, both of whom embraced and analyzed Freud (there is only one brief text by feminist Eva Figes) to make provocative claims about the link between sexual difference and gender norms. It ignores altogether Freud’s centrality to the clash between Zionists and their opponents, who disagreed on Jewish nationalism’s capacity to “solve” the mental scars inflicted by antisemitism. But perhaps more important, focusing on Civilization and Its Discontents’ political legacies can distract from its less explicit, but ultimately more relevant and disturbing message about the centrality of contradictions, ambiguities, and uncertainties to human existence.

Freud communicated this argument through the book’s unusual style and organization, which often goes unmentioned by commentators but is one of the main reasons it makes for such a captivating read. Unlike other social theorists, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau or Karl Marx, Freud did not present his ideas with self-assured confidence. Instead, he constantly highlighted his doubts and frustrations, following his claims with complaints that they were banal and floating hypotheses only to retract them as misleading. Similarly, the book’s structure defied the standard of social theory, in which one argument logically builds on another. Freud instead presented his ideas through a stream of free associations and regressions, jumping frantically from reflections on technology to footnotes on humans’ relationships with dogs. This choice, of course, was hardly coincidental. Freud sought to impress on his readers a sense of relentless puzzlement, to spark resistance to neat arguments.

Freud’s focus on uncertainty and contradictions is also reflected in the book’s content, especially its deeply gendered claims about the relationship between individual ambitions and society. In one passage, Freud claimed that civilization was a sublimation of human ambitions. This was why it was “increasingly the business of men”: because their aggressive impulses were exceptionally strong, they were eager to sublimate them into politics, science, and art, in the process expelling women “into the background.” Yet in a different section, Freud claimed that women were the original guardians of civilization, exactly because they knew how to limit their ambitions. He speculated that in prehistoric times, they were the ones who learned to cultivate fire, an “extraordinary and unexampled achievement” that men achieved much later (because their infantile obsession with their penises meant they sought to extinguish fire with pee). The tensions between these claims—is civilization the product of ambition or the denial of ambition? The work of men or women?—is compounded by an additional commentary in which Freud wondered if sexual differences were truly that foundational. Humans, he wrote, are creatures “with unmistakably bisexual dispositions,” who blended desires and psychological traits of both sexes, adding that it’s unclear male and female even have different psychological makeups.

Civilization and Its Discontents reveals similar ambiguities when it explores sexual repression. Throughout the book, Freud ruminated about civilization’s costs for human sexuality. The enormous pressure to channel all desire into heterosexual marriage, he mourned, severely undermined people’s ability to enjoy sex, the most basic and intense pleasure available. But in a telling passage, Freud noted that there might be something about the nature of sexual attraction that prevented seamless enjoyment. After all, people often were repelled by some aspects of the sexual act, such as the smells involved. As he put it, “sometimes one seems to perceive that it is not only the pressure of civilization but something in the nature of the sexual function itself which denies us full satisfaction and urges us along other paths.” In a blunt admission of uncertainty, Freud followed this sentence by explaining he was unsure which of his claims was more accurate. “This may be wrong,” he noted. “It is hard to decide.”

Perhaps

most striking, Freud questioned his book’s fundamental dichotomy between social

stability and aggression. Civilization and Its Discontents famously

opens with Freud’s reflections on “the oceanic feeling,” a sense (reported by the

novelist Romain Rolland) of limitless connection with the universe. This feeling,

Freud claimed, which is common to religious believers, was a childish

psychological consolation: It was a narcissistic joy that civilization provides

to help some people handle the repression of their desire to destroy. As

literary scholar Leo Bersani however noted, later in the text, Freud used the

very same words to describe the psychological forces from which civilization protects.

When one is possessed by rage, “in the blindest fury of destructiveness, we

cannot fail to recognize that the satisfaction of the instinct is accompanied

by an extraordinarily high degree of narcissistic enjoyment.” Both aggression

and its repression, it seems, produce the same sensation. Freud thus speculated

that civilization turned our own aggression against us. As he put it, when one

internalizes society’s rules (which we all do), we “put into action … the same

aggressiveness that [one] would have liked to satisfy upon other, extraneous

individuals.” Aggression and civilization, it seems, are not antagonists. They

are identical twins.

Rather than a political tract, then, Civilization and Its Discontents can be understood as a mediation about the inevitability of contradictions, paradoxes, and confusions. Being human, Freud seemed to claim, is to accept that our understanding of the world is always partial and misguided, with all the misery this entails: We can never know if the source of our unhappiness is social conditions or individual idiosyncrasies, or whether our actions, individual or collective, increase or diminish our suffering. Social theorists, whether progressive, centrist, or conservative, may strive to produce clear categories for analysis and offer neat solutions for human dilemmas. But as Freud’s doubts about his own ideas show, in his eyes, this was as futile as distinguishing between civilization and its discontents.

After two years with an unpredictable virus, the mental price of uncertainty has been increasingly the center of attention. Even those of us who were earlier shielded from the pandemic’s more extreme manifestations (by luck or wealth), have been relentlessly taxed by psychological disorientation: agonizing over not knowing if our children’s adherence to health guidelines will forever diminish their social skills, if our interactions with family and friends could unexpectedly lead to illness, if the job that financially sustains us also puts us at risk, or whether a new variant is yet again going to upend our lives. The sense of gloom has been exacerbated by the threat that lurks behind every social interaction. From sport events to museums to cafes to restaurants, the most basic joy of engaging with others is now tainted by the threat of infection. In this reality, daydreaming about life after Covid-19 can be a rare source of solace. Next month or next year, we tell ourselves, it will be “over,” and things will be back to “normal.”

If Civilization and Its Discontents is right, however, no rescue is on the horizon. Even after this pandemic recedes into history, our psyche will remained depleted. This is not only because “normal” was always rife with injustices and because of the social impetus to repress our urges. Just as important, it’s because we are destined to live with bewilderment. It is unclear if the reissuing of Freud’s book was related to the explosion of Covid or whether the two just accidentally coincided. But in its grim and tragic outlook, it is just the work for our times.