In 1888, a young Russian actor named Konstantin Stanislavski was cast as the lead in a production of Alexander Pushkin’s The Miserly Knight. Stanislavski was then in his mid-twenties, and he struggled with playing the title character, an elderly aristocrat who spends his nights obsessively counting the treasures he’s hoarded in the cellar of his ancestral castle. He studied the gestures of old men and practiced them in front of his mirror, but when he presented what he had worked up in rehearsal to the play’s director, he was told that his carefully honed performance resembled “a child’s idea of an old man.”

Back to the drawing board! “Whenever Stanislavski felt lost,” Isaac Butler writes in his compelling, meticulous new history, The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act, “he researched his way forward”:

Perhaps, he thought, he could understand the Miserly Knight’s solitude by experiencing it himself. So he tried a kind of research that, a century later, would become standard practice in the long line of actors who claimed to follow in his footsteps: He tried to live as his character lived. He traveled to a castle and had the staff lock him in its basement, but all he picked up was “a bad cold and despair.”

What might seem like a suspiciously perfect origin story for the immersive preparations now commonly associated with Method acting—an attempt “to live as his character lived”—in fact proved to be a false start; Stanislavski mentions it in his 1924 biography, My Life in Art, only to mock his own youthful folly. “Apparently, to become a tragedian it was not enough to lock myself in a cellar with rats,” he wrote. “Something else was necessary. But what?”

The rest of Stanislavski’s career would be devoted to specifying this “something else.” He would go on to devise a set of theories and techniques he called “the system,” which would mutate, after being imported to the United States, into “the Method,” and completely transform American theater and film. In his search, Stanislavski introduced the idea that great acting is not a matter of personal charisma or divine inspiration but of intellectual rigor and critical intelligence. What kind of preparation is necessary, he asked, to achieve “a state of living within the ‘very middle of an imagined life’”? Stanislavski’s ultimate importance lies not in the specific answers he arrived at so much as in the fact that he believed the question could be answered at all. By his own lights, he stumbled on as many wrong ideas as he did right ones in the course of his investigations; what is strange is that, over a century later, no one seems to agree which ones are which.

The man who would become Konstantin Stanislavski was born Konstantin Alekseiev in 1863 in Moscow. He was the scion of wealthy industrialists, and he dutifully did his part to manage the family business, overseeing factories manufacturing gold and silver thread. In his spare time, however, he pursued a parallel career as an actor and director under the pseudonym “Stanislavski” (chosen, initially, to spare his family embarrassment). In class terms, Stanislavski was a bourgeois; as an artist, he was a radical. He despised the artificiality of the nineteenth-century Russian theatrical establishment, which was rooted in conventions imported from Europe a hundred years earlier. “I am waging a fierce struggle against routine in our theater,” he declared. “It is the task of our generation to banish from art tradition and routine … that is the only way to save art.” For Stanislavski, the existential stakes of his mission could not be higher: “The artist,” in his estimation, was “a prophet who appears on earth to bear witness to purity and truth.” His passion for artistic authenticity had a moral, even religious fervor: “All disobedience to the creative life of the theater is a crime.”

The Moscow Art Theatre, which Stanislavski founded with his partner, Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, in 1898, quickly became known as one of the finest theatrical companies in the world. It would go on to present the first successful productions of Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull, Uncle Vanya, The Three Sisters, and The Cherry Orchard, as well as works by Ibsen, Shakespeare, and emerging young Russian playwrights like Maxim Gorky. Unlike most nineteenth-century theaters, which pulled from itinerant ranks of freelance actors, the MAT maintained a permanent ensemble trained in Stanislavski’s bespoke performance techniques. They also devoted extravagant amounts of time to rehearsal—as long as 14 months, on occasion. They lavished as much attention on minor parts as on lead roles: “Today Hamlet, tomorrow a supernumerary,” ran another of Stanislavski’s aphorisms, “but even as a supernumerary you must become an artist.”

Stanislavski also pioneered the process of script analysis, which involved annotating and sometimes diagramming each line of a play. Butler describes “an invented hieroglyphic notation mapping out the characters’ emotional states. An ear meant ‘listen,’ an ear in brackets meant ‘listen quietly.’ An arrow going up meant ‘the transition from apathy to the creative state,’ while an arrow ending in a hook meant ‘spiritual cunning and conviction,’ and so on.” Preparations were extensive and often eccentric; during rehearsals for a production of Ivan Turgenev’s A Month in the Country, for instance,

Stanislavski cut the laborious monologues and forced the actors to communicate the text as “radiating” their thoughts out wordlessly, while their fellow actors attempted to “receive the arrows” of these thoughts. At times, they’d be restricted to solely using their eyes, furiously thinking at a mystified scene partner seated across the table.

The objective of these sometimes bizarre procedures was simple enough: realism. Stanislavski and his collaborators eschewed the grandiose, declamatory style of traditional Russian theater in favor of a naturalistic approach rooted in the observation of everyday human behavior. Actors were encouraged to focus entirely on their characters and the “given circumstances” of the play, and to ignore the existence of spectators entirely. No more playing to the gallery; the Stanislavskian ideal was a state of “public solitude.” He taught “the art of appearing as if you do not realize you are being watched.”

Stanislavski was a working director first and foremost; his “system” (which he always buttressed with quotation marks, to indicate its provisionality) was a by-product of his practice, not an airtight aesthetic theory. He also “had a habit of disavowing his own statements,” according to Butler; “when watching one of his own exercises conducted by someone else,” he once asked, “What idiot thought that one up?”

Nonetheless, the allure of the “system” and the image of Stanislavski as a master theorist were key parts of the Moscow Art Theatre’s international prestige. It also made the organization somewhat suspect in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. The new Bolshevik government nationalized the theaters (along with the Alekseiev family’s factories) and put pressure on the MAT to present material that was ideologically consistent with Soviet Communism. The content of “the system” came under particular scrutiny during the Soviet years, so much so that Stanislavski was forced to write two different editions of his 1936 handbook, An Actor Prepares, one for Russia and one for the United States, in order to downplay the debt his thinking owed to bourgeois psychology.

Outside Russia, though, Stanislavski’s fame was growing. In 1922, the Moscow Art Theatre undertook its first tour of the United States, performing its repertory for rapt American audiences and solidifying its reputation among the cognoscenti. Around the same time, several members of the MAT immigrated to the United States, and two of those exiles, Richard Boleslavsky and Maria Ouspenskaya, became Stanislavski’s preeminent American emissaries. Many of Boleslavsky’s and Ouspenskaya’s students would subsequently cluster around the Group Theatre, a left-wing experimental company formed in New York City in 1931, which included the future Method acting teachers Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, and Sanford Meisner, the agitprop playwright Clifford Odets, and the director Elia Kazan, whose films with Marlon Brando and James Dean would bring the Method to a mass audience in the 1950s.

The Group was full of strong personalities, but Strasberg took an outsize role early on. He was an imperious, demanding director, ruthlessly devoted to critiquing his actors and rooting out all signs of artifice or falseness in their performances, and he developed an almost cultlike charisma as leader of the Group and, subsequently, of the Actors Studio, a more explicitly pedagogical institution founded in 1947. Karl Malden, a Group alumnus who appeared opposite Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire and On the Waterfront, spoke of the Actors Studio being suffused with “‘a horrible crippling fear’ that originated with ‘Lee’s personality.’” The director Arthur Penn described Strasberg as “a damn near despotic and frightening figure.” The theater critic Gordon Rogoff, who briefly worked at the Actors Studio, wrote that if Strasberg “is a genius at anything, it is in the fine art of inspiring insecurity.”

In his teaching and directing, Strasberg stressed the idea of “affective memory”: the notion that actors could harness their own past experiences in order to trigger onstage emotions appropriate to their characters. While Stanislavski had indeed sometimes encouraged his actors to work with their personal memories, he was far less committed to the practice than Strasberg, who upped the ante by pushing actors to explore the most painful episodes from their past in order to unlock emotion; his student Shelley Winters would later call this (approvingly) “act[ing] with your scars.” The process indisputably got results, but it also took a psychological toll on actors when employed consistently over time. Yet Strasberg continued to emphasize affective memory as a crucial tool of the Method, even in the face of actors’ resistance; by the 1950s, it was one of the techniques most associated with Method acting, American style.

Strasberg’s commitment to affective memory was absolute, and it precipitated one of the first major schisms within American Stanislavskian circles. In 1934, Stella Adler—one of the Group Theatre’s star performers, who had come up as a child actress in the Yiddish theater—was given the chance to meet Stanislavski on a trip to Moscow, and she used the opportunity to complain to him about the psychological damage that Strasberg’s application of “the system” was doing to her. “Mr. Stanislavski, I loved the theatre until you came along, and now I hate it!” Adler is supposed to have said. Surprisingly, Stanislavski was sympathetic to her complaint, and explained to Adler that “the Group had gotten his ‘system’ wrong”: He no longer used emotional memory exercises in his own teaching, preferring to remain within the world of the play and emphasize the character’s motivation—the problem that a character is focused on in a set of given circumstances.

This historic meeting—the details of which are much disputed—empowered Adler to break with the Group and form her own offshoot of the Method, distinct from Strasberg’s, which emphasized motivation rather than affective memory. The most important thing, Adler taught, was for an actor to know what their character wanted in any given moment: Everything else would flow from that. The principle is nicely illustrated by an anecdote Butler relates about the young Marlon Brando, who was one of Adler’s star pupils. One day, as an exercise in improvisation, Adler instructed her acting class to imitate farm animals; “Brando played a chicken”:

At some point in the midst of their walking around an imaginary barnyard, Adler told the class that an atomic bomb was about to fall. Everyone in the class started running around, flapping their wings, clucking, displaying animal panic. Brando waddled over to his invisible nest and sat on some imaginary eggs. What did a hen know from the bomb?

Though Method acting is frequently associated with a high pitch of emotive intensity, the Stanislavskian lesson here is that the actor should care only about what their character would care about: nothing more, nothing less. If you’re a chicken, concentrate on your eggs.

Lee Strasberg is frequently cast as the villain in accounts of the Method, though Butler is careful to give him his due. (There was certainly no love lost between Strasberg and Stella Adler; when she learned of his death in 1982, her reaction was gleeful: “Good riddance. He will finally stop destroying actors.”) The vogue for Method acting in the United States coincided with the popularization of Freudianism, and many accused Strasberg of setting himself up as an ersatz psychoanalyst. Especially controversial was his mentorship of Marilyn Monroe, who began taking classes with Strasberg in the mid-1950s, and who subsequently hired his wife, Paula, as her acting coach. Some members felt the Strasbergs were exploiting Monroe’s celebrity to generate publicity for the Actors Studio, while at the same time pushing her to revisit past traumas, including her sexual abuse, in ways that were harmful to her mental health at a time when she was struggling with drug addiction.

But Strasberg was certainly not the only advocate of the Method to step over the line into emotional, or even physical, abuse. Elia Kazan extracted real tears from the 12-year-old Peggy Ann Garner for a key scene in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by suggesting that her father, who was serving in World War II, might not return home alive. (“Her outburst of pain and fear was essential to her performance,” Kazan recalled later. “It was the real thing. I was proud of that scene, its absolute truth.”) Marlon Brando often antagonized his female co-stars, taking a sadistic pleasure in throwing them off balance. “In a scene from Reunion in Vienna,” Butler tells us, “Brando surprised Joan Chandler by slapping her, kissing her, and deadpanning the invented line ‘How long has it been since you were kissed like that?’ The audience erupted in laughter. Brando continued, pouring champagne down Chandler’s bodice, improvising lines, and cracking everyone up.” Stories like these, which frequently turn on men assaulting and berating women, are part of how the Method has earned a reputation as inherently misogynist, an assumption that has only recently begun to be questioned by feminist scholars like Shonni Enelow and Keri Walsh, who have noted the prominence of women like Adler, Cheryl Crawford, Kim Stanley, Shelley Winters, and Geraldine Page in the movement.

By the end of the ’50s, the Method had lost much of its cachet in theatrical circles. The postwar avant-garde was more interested in the anti-naturalism of Brecht and Beckett than in Stanislavski’s strenuous realism, and in more commercial circles Method actors had acquired a reputation for self-indulgent unprofessionalism. (A well-known anecdote has Broadway producer George Abbott replying to the traditional Method actor’s query “What’s my motivation?” with “Your job!”) But during the same period the Method was becoming increasingly influential in the film industry, which had begun to absorb key players from the Group Theatre as early as the mid-1930s. Butler explains the Method’s steady rise in Hollywood as at least partially a by-product of changes in film technology. “Talkies … demanded a new style of acting,” he explains. “Silent films required a heightened physicality from the actor because their stories were told through gesture and facial expression. But with the advent of sound … the physical style of acting became more restrained, and performances turned increasingly naturalistic.” The movies needed actors who could communicate subtlety and who seemed like real people, values that aligned conveniently with Stanislavskian aesthetics.

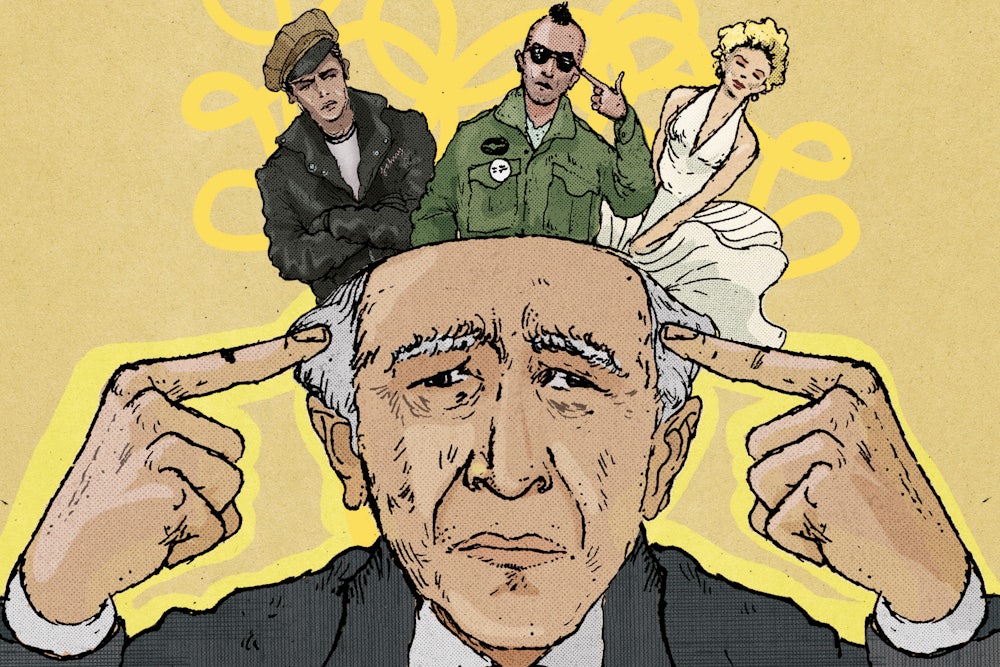

A first wave of Method-trained movie stars came to prominence in the 1940s and ’50s, including Marlon Brando, Kim Stanley, Montgomery Clift, Rod Steiger, and James Dean. Initially, Method actors were regarded as outsiders in Hollywood. The Method’s best practitioners were often, as Butler astutely notes, “proletarian children of immigrants,” and they were faulted for their lack of classic movie-star glamour: The gossip columnist Hedda Hopper called the Method “the dirty shirt school of acting.” They were especially ridiculed for their voices: Butler contrasts the odd, accented, often mumbled speech of Method actors like Brando and Steiger with the polished “mid-Atlantic” elocution of golden age Hollywood stars like Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant.

But these objections gradually dwindled as the Method infiltrated the mainstream of film acting. A second wave of Method-trained stars, including Dustin Hoffman, Warren Beatty, Al Pacino, and Ellen Burstyn, would emerge in the ’60s and ’70s and play a crucial part in the much-vaunted “New Hollywood.” Butler points out that, in 1979, nine of the 10 Oscar nominees for acting were alumni of the Actors Studio. Strasberg himself appeared, at Al Pacino’s behest, in The Godfather: Part II as Jewish gangster Hyman Roth; this was also the era during which he could be glimpsed riding around Los Angeles “in a Mercedes with a license plate that read METHOD.”

As the Method became more broadly influential, it inevitably lost some of its rigor, becoming a catchall term for any unusually dedicated or demanding performance. In contemporary discourse, the phrase “Method acting” often refers primarily to the degree of intensity that an actor brings to a role, rather than to particular techniques or concepts that can be traced back to Stanislavski or his followers. In Butler’s telling, the person most responsible for what most people think of as “Method acting” today is Robert De Niro, who studied briefly with Stella Adler but is in many ways a singular, idiosyncratic figure in the history of acting. De Niro took the Stanislavskian ethic of rigorous preparation to an extreme without being beholden to the dogma that had grown up around the Method in the United States. (He has called the Actors Studio “a cult of personality.”) For one film, he asked the actress cast as his wife to live on set with him in order to better simulate married life. Most famously, he gained 60 pounds for the role of boxer Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull and remained in character throughout production, insisting that he be referred to as “Jake” or “Champ” at all times.

“De Niro’s performance [in Raging Bull]—and the esteem and awards it garnered—changed the American public’s understanding of what Method acting was,” Butler contends:

As elaborate tales of preparation, research, and physical transformation became a major component of media and award campaigns, the Method became synonymous with a baroque process by which an actor lives as a character, transforms their body, and refuses to stop acting once on set.

Butler is adamant that this kind of thing, impressive as it is, has little to do with Method acting. He notes that the (mostly male) contemporary actors most associated with these kinds of extreme preparations—Daniel Day-Lewis, Joaquin Phoenix, Jared Leto, Christian Bale—have no formal training in the Method; indeed, they often deliberately eschew it. A recent New Yorker profile of Jeremy Strong, who is often identified as a Method actor, describes him attending a college acting class where “the professor talked about Stanislavski and drew diagrams of circles of energy.” Strong was repelled: “‘I remember feeling, I need to run from this and protect whatever inchoate instinct I might have.’” In many ways, in fact, the process modeled by De Niro more closely resembles the young Stanislavski’s clumsy attempts to embody the Miserly Knight by locking himself in a basement overnight than it does the Method as it evolved in the United States. (Back to the drawing board!)

Even as he catalogs the Method’s many flaws and abuses, Butler is reverent about the history he records, and more than makes the case for the Method’s salutary effect on twentieth-century acting. About its modern-day legacy, he’s a bit more sanguine. Clearly, the ideas of Stanislavski and his successors have helped several generations of actors to think about their craft and take it seriously; along the way, it has helped inspire some transcendent performances. But the “Method” mindset, as it has evolved since De Niro, has increasingly made a fetish of individual mastery in ways that are antithetical to the collaborative spirit of both the Moscow Art Theatre and the Group Theatre. One could argue that the extreme feats of transformation undergone by modern-day “Method” actors are ways of compensating for the lack of what Stanislavski considered most essential: time to rehearse, annotate, and discover the truth of a play collectively. The techniques that De Niro pioneered were developed for movie sets, on which scenes are interrupted by stops and starts, rehearsal time is short or nonexistent, and acting is often subordinated to a myriad of technical considerations; actors like Strong have adapted them to television, where schedules and resources are even tighter.

Stanislavski taught that everyone involved in the production of a play—even the “supernumeraries”—should regard themselves as artists. But today’s “Method” performances are almost invariably star turns, and, as dazzling as the final product can be, there is something fundamentally antisocial about them, as if the actors take for granted that artistic truth won’t matter enough to one’s collaborators to emerge organically out of the ordinary process of production, and must be sought in single-minded, quasi-monastic focus on self-discipline. “One must love art, and not one’s self in art,” Stanislavski once wrote, but in many ways the legacy of the Method is exactly the opposite: It’s given actors a new way to love themselves.

This article appeared in the March 2022 print edition with the headline “Risky Realism.”