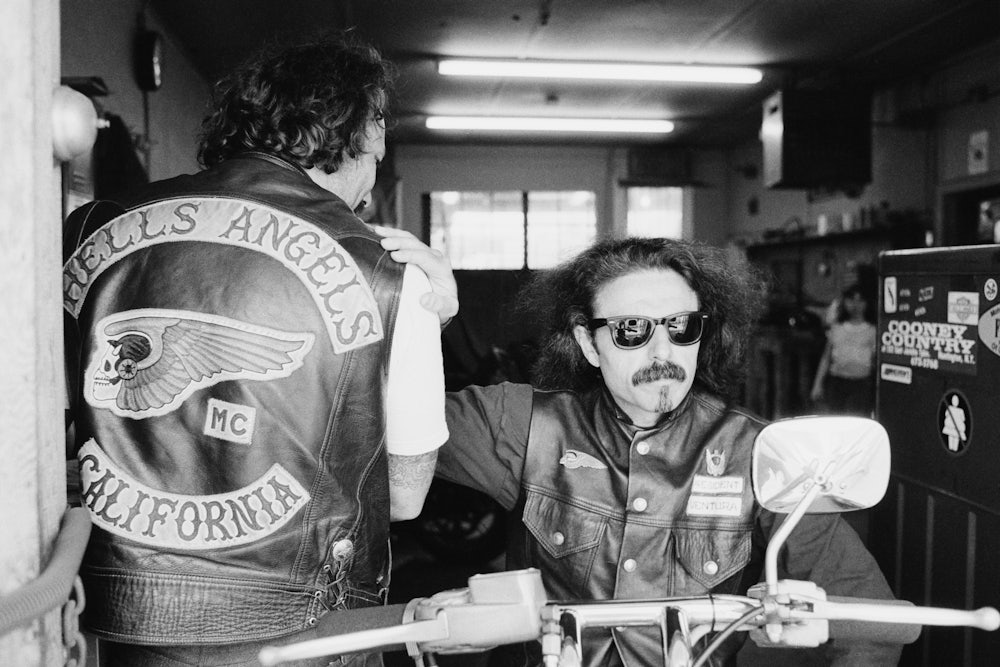

Hunter S. Thompson doesn’t think

much of the “button-down” lives of

the squares. He likens them to “ribbon

salesmen,” enslaved to their “time payments,” at best hypocritical pseudo-hipsters when they try to swing, and,

at worst, the liberal persecutors of the aberrant, or victims of affluence and

“abulia,” and the creators of a mass

hysteria toward California’s obscenely

festooned gangs of motorcycling Hell’s

Angels which has only helped to glamorize and institutionalize their “outlaw” status, lending to their shabby

Wehrmacht muftis and atavistic sleeziness a high-Camp prestige and a

Charisma for exceeding the actual numbers of those who have been so

attired.

Thompson also concedes that these “losers” on wheels are a threat to the self-satisfied bourgeoisie, but he takes great delight in exposing what has merely been invented and advanced about them by the mass media out of an opportunistic need to make eye catching copy, and what Angel offenses are actual.

For example, after the brouhaha ever Kenneth Anger’s film Scorpio Rising, a homosexual motorcyclist fantasy but not a Hell’s Angels film, Thompson points out, the square press “relegated” the outlaws to “new nadirs of sordid fascination. Mere than ever before,” he explains, “they were wreathed in an aura of violent and erotic mystery ... brawling satyrs, ready to attempt congress with any living thing, and in any orifice. ...”

He then goes on to locate the Angel’s threat to the square world in square ambivalence. Angels are “an instrument of anarchy, a tool of defiance, and even a weapon.” “A Hell’s Angel on foot can look pretty foolish,” he asserts “ ... their everyday scene is as tedious and depressing as a costume ball for demented children. . . . But there is nothing pathetic about the sight of an angel on his bike. The whole-man and machine together - is far more than the sum of its parts. ... It is his only valid status symbol, his equalizer. ...”

All of these remarks appear in the context of Thompson’s fascinating invocation to, evocation of, and reportage about the Hell’s Angels which, to pay it what may seem like a left-handed compliment, is certainly the most informative, thorough, and vividly written account of this phenomenon yet to appear. And no wonder! Thompson spent better than a year among the Angels. He is himself an accomplished motorcyclist, familiar, it would seem, with the drug and “acid” scenes. He was also eventually “stomped” by the Angels.

In the course of his investigation, Thompson may slight making the obvious connection between the motorcycle fad in this Country and that in pre-Hitlerian Germany under Weimar, but he makes a let of other interesting connections between the Hell’s Angels and present-day square society, especially its liberal elements, Although Thompson seems to have elevated the outlaws for himself to “new nadirs of sordid fascination,” he has also managed to correct many popular misconceptions about them, and, in the process, provided his readers with a tendentious but informative participant-observer study of these who are doomed to lose. Yet his work might shortly be relegated to the souvenir bins of a rapidly-changing faddist era were it not for the assertions which Thompson makes about the proliferation of “losers” in our society, and for his talents as an imaginative writer.

Very simply, Thompson believes that the “unemployables” and the deracinated are on the ascendency in American life - that, in short, Hell’s Angels are the avant garde of a new lumpen class. He is able to trace this class to the Hillbilly descendants of the indentured servant classes who came to this country two centuries ago and have only recently begun to appear in cities in large numbers, as well as to a fallout from other mere recent ethnic groups, and, of course, to the resentfuls within the black ghettos. While he is generally in sympathy with such plights, even comparing such lumpen behavior to the spontaneities of the Watts rioters, he further manages to see a peculiar integrity to this kind of behavior which is in increasing conflict with a society upholding property, education, and restraint.

And if what Thompson tells us about Hell’s Angels is true, we squares certainly do have reason to be fearful. Angels initiate their fellow members by collecting their mutual excreta in a bucket and then dumping it ever the fellow’s head. They are practitioners of the recriminatory gang-bang and the mass rape. Like all outlaw groups, they have their own codes of honor and their own emblemology. Red wings on an Angel’s back advertise that he has practiced cunnilingus with a menstruating woman. Black wings, as I recall, advertise buggery. If all that seems threatened here is a minor constituency of the public health officials, then, of course, Thompson’s point is missed. It’s not simply the spreading of clap, crabs, and other disreputable diseases; its a particular kind of social disarray that seems imminent:

“Consider the reaction of the middle-aged roofing-and-siding salesman, cruising along with his wife and two children in the family Mustang on a remote stretch of Highway 101. Something in the engine begins to clank, so he pulls onto the shoulder and begins to look. Suddenly he hears a rumble of motorcycles. A dozen Hell’s Angels pull over, get off their bikes, and walk toward him. Thinking quickly, he jerks the oil dipstick out of his engine and begins lashing at the thugs. His wife, terror-stricken, leaps out of the car and runs into a nearby cornfield, weaving through the stalks like a lizard. The children cower, the man is punched, and moments later a Highway patrol car arrives. The outlaws are jailed on $5,000 bond for aggravated assault and attempted rape ....”

Imagine this multiplied by the thousands of incidents, as Thompson’s vision would have it, and, unless I am mistaken, what he actually seems to be projecting through such set pieces of comic, anti-square exaggeration is a future reign of anarchy and terror, a new order perhaps, civil war between the squares and the lumpen strata. Then even the pseudo-hippies will be called before the inscrutable bar of lumpen justice; for, as Thompson observes, when push came to shove recently in California, the Angels thought nothing of attacking anti-Vietnam demonstrators despite the exhortations for camaraderie of the guru Allen Ginsburg and like-minded other Berkleyites.

Taken, then, as a delirium for the future, Thompson’s book is a hairily comic metaphor for a society getting just about what it deserves for napalming Vietnamese and instituting privilege for everybody except those who need it most; and it’s a metaphor which, even in its grotesque nonsensicality, manages to scratch a bit of the truth off the American veneer. I have the feeling, however, that should that day of ultimate integrity ever arrive, advocates such as Thompson may find themselves treated worse than simply being stomped. What utility, after all, would guru poets and motorcycling novelists of talent and integrity have in a society dedicated only to the integrity of the brutal? Yes, it’s only because there are so many middle-class squares in America that Thompson has the means and the audience with which to epater these very same bourgeois.

If push comes to shove, therefore, Mr. Thompson may end up as poet laureat of the Angels, but who will take the trouble to keep track of his royalty statements? Who will bother to read his finely worked prose ecstasies? To judge from the recent history of other nations, such a state may not even benefit the Angels. It was, after all, the orgiastic brownshirted SA of Rohme who were purged first when the Weimar anarchy brought the Nazis to power. So Mr. Thompson (and others like him in Berkeley and elsewhere) is hung on his own paradox: If only the square and generally liberalminded bourgeoisie persecutes the Angels, they are also the only kind of ascendant order which would tolerate them:

“Early, with ocean fog still on the streets, outlaw motorcyclists wearing chains, shades, and greasy Levis roll out from damp garages, all-night diners, and cast-off one-night pads in Frisco, Hollywood, Berdoo, and East Oakland ...The Menace is loose again, the Hell’s Angels, the hundred - carot headline, running fast and loud on the early morning freeway, low in the saddle, nobody smiles, jamming crazy through traffic and ninety miles an hour down the center stripe, missing by inches ... like Genghis Khan on an iron horse, a monster steed with a fiery anus, flat out through the eye of the beer can and up your daughter’s leg with no quarter asked and none given ....”

And lest this seem like a mere evocation of the envious square’s eye view of these grizzled monads bumping up against one another and doing mostly themselves violence, Thompson appends a short prose poem again, at the book’s end, evoking his own violent motorcycling aesthetic:

“It has to be done right ... and that’s when the strange music starts, when you stretch your luck so far that fear becomes exhilaration and vibrates along your arms. You can barely see at a hundred ... You watch the white line and try to lean with it ... letting off now, watching for cops, but only until the next dark stretch, and another few seconds on the edge ... The Edge ...There is no honest way to explain it because the only people who really know where it is are the ones who have gone over ....”

In the work itself, Thompson’s self-proclaimed aesthetic and his methodology have some of the integrity of George Orwell among the poor of London and Paris, and it also has the cranky peevishness of Orwell’s fine attack in Wigan Pier on pseudo-leftists, progressives, and food faddists, but it seems to have dispensed with the very middle-class biases toward “decency” which Orwell tried so hard to assert and uphold. Rather, it asserts a kind of Rimbaud delirium of spirit for nearly everybody to which, of course, only the rarest geniuses can come close and, then, never through choice. For more than one reason, therefore, I suspect, that Hunter S. Thompson is a writer whose future career is worth watching.