Fifty years after the publication of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Hunter S. Thompson’s celebrity remains a durable fact. Yet there was nothing inevitable about his notoriety or the style that gave rise to it. Gonzo journalism—Thompson’s unique blend of hyperbolic commentary, satire, invective, hallucination, and media critique—developed unevenly, haphazardly, almost by accident. That body of work, and the rock-star celebrity it created, almost didn’t happen.

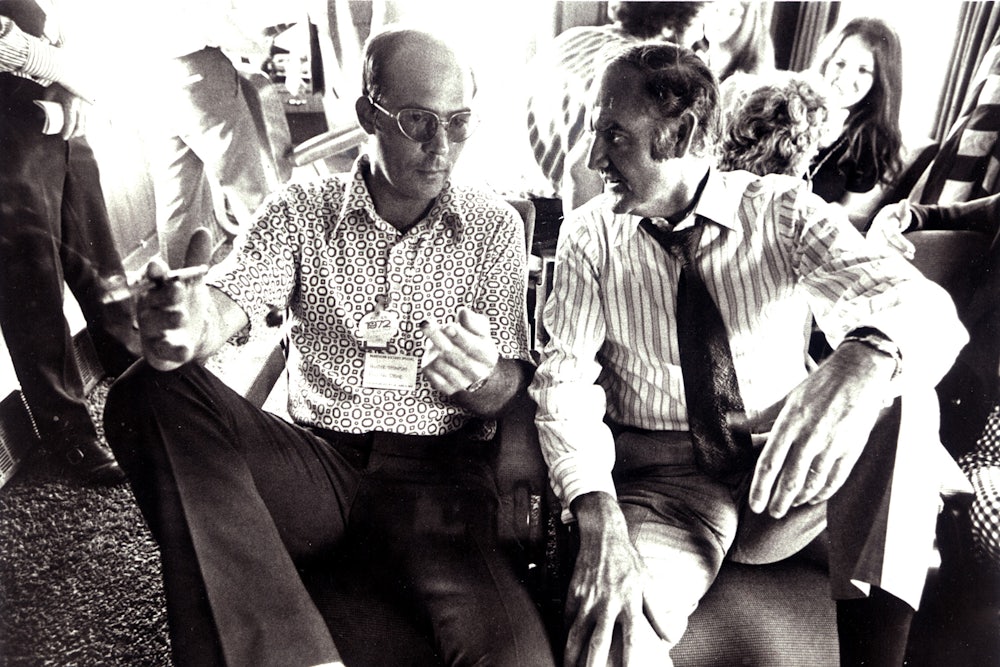

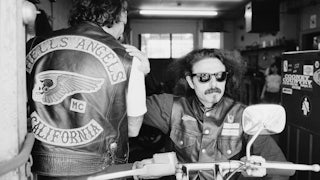

In 1965, Thompson was a freelancer begging for assignments when The Nation commissioned an article on the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang. Thompson parlayed his first-person account into a bestselling book, and Random House quickly signed him for three more titles on short schedules. The second book stalled, however, and Thompson struggled with his magazine work. Playboy spiked his lengthy profile of Jean-Claude Killy, the Olympic skier who became a pitch man for Chevrolet. Fortunately for Thompson, Warren Hinckle ran the Killy piece in the premiere issue of Scanlan’s Monthly.

Hinckle also published “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved,” Thompson’s 1970 account of the famed sporting event—or rather, the drunken revelry surrounding it. Illustrated by Ralph Steadman, that piece is usually considered the first work of gonzo journalism. Thompson set the debauchery at Churchill Downs against a backdrop of political violence—including President Nixon’s bombing of Cambodia and the slaughter at Kent State University, which occurred the same week as the Derby. Finishing the story was an ordeal, and Thompson considered it an abject failure. When it was heralded as a breakthrough, he compared the experience to “falling down an elevator shaft and landing in a pool full of mermaids.”

Thompson’s next articles skipped the gonzo pyrotechnics, but “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” which Rolling Stone ran in November 1971, etched gonzo journalism in the public imagination. Based on a pair of wild weekends in the desert, the two-part article was a freewheeling epitaph for the 1960s counterculture. It made a bigger splash than the Kentucky Derby piece, but in a letter to James Silberman, his editor at Random House, Thompson worried that it would diminish his credibility as a serious journalist. Once again, he had underestimated gonzo’s career-altering appeal.

Gonzo journalism thrived at Rolling Stone, especially during the Nixon era. As the decade wore on, Thompson’s outsize persona—which featured his drug consumption, gun fetish, and “fortified compound” near Aspen—began to eclipse his work. Yet Thompson understood his literary gift quite apart from his celebrity. In 1975, he correctly described himself as “one of the best writers currently using the English language as both a musical instrument and a political weapon.”

But how, exactly, did Thompson achieve that status in a single decade? With the benefit of hindsight, we can identify four separate developments that pushed Thompson toward his unique niche in the media ecosystem.

Chicago

Early in his career, Thompson admired the Kennedys, detested Nixon, and attended the 1964 GOP convention in San Francisco. Even so, he considered American politics a dead end. He wanted to follow the example set by Tom Wolfe in The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (1965). An early version of the New Journalism, that book featured Southern California’s hot-rod scene as well as the spectacular growth of Las Vegas. Later, Wolfe profiled the psychedelic scene around novelist Ken Kesey, whom Thompson had introduced to the Hell’s Angels. In short order, Thompson also carved out a niche as a student of exotic West Coast subcultures.

His outlook changed dramatically in 1968. By that time, Thompson had befriended Hinckle, who presided over Ramparts magazine. Through his connection with the legendary San Francisco muckraker, Thompson learned that all hell would break loose at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. He asked Silberman to obtain press credentials for him and booked a trip to Chicago. His sources were correct: Thousands of demonstrators flooded the streets and public parks, and police officers flayed provocateurs, peaceful protesters, and observers alike. The clashes provided a dramatic backdrop for the debates inside the convention, especially over the party’s position on the Vietnam War. Senator Edmund Muskie maintained that the anti-war contingent wanted peace at any price, the peace plank was defeated, and Hubert Humphrey received the party’s nomination. By the end of the convention, both Humphrey and Muskie earned Thompson’s lasting contempt.

The real story was in the streets, however, where Thompson recoiled from the police violence he witnessed. Scampering from agitated cops on Michigan Avenue, he encountered two officers blocking his retreat to his hotel. As he later recalled, “I finally just ran between the truncheons, screaming, ‘I live here, goddamnit! I’m paying fifty dollars a day!’” Thompson told Silberman that the street battles made “all the Berkeley protests look like pastoral gambols from another era.” In Chicago, the protesters “stood and fought, and took incredible beatings. I witnessed at least ten beatings in Chicago that were worse than anything I ever saw the Hell’s Angels do.” For that reason, Thompson added Democratic Mayor Richard Daley to his list of villains.

Thompson published very little about Chicago, but the police riot shocked him into a deeper personal, civic, and professional reckoning. “That week at the Convention changed everything I’d ever taken for granted about this country and my place in it,” he wrote later. “I went from a state of Cold Shock on Monday, to Fear on Tuesday, then Rage, and finally Hysteria—which lasted for nearly a month. Every time I tried to tell somebody what happened in Chicago, I began crying, and it took me years to understand why.”

Before the convention, Thompson profiled artists in Big Sur, activists in Berkeley, and motorcycle gangs in San Francisco and Oakland. That strategy established his place in the New Journalism pantheon, but especially after Chicago, Thompson took direct aim at the nation’s most powerful politicians.

Steadman

The second step toward gonzo journalism was Thompson’s pairing with Ralph Steadman. When Thompson pitched the Kentucky Derby idea to Hinckle, he asked that political cartoonist Pat Oliphant produce the illustrations. Oliphant declined, and Hinckle chose Steadman, whose work he had seen in Private Eye. Founded in 1961, the English satirical news magazine modeled some of what Hinckle created at Ramparts and Scanlan’s.

After meeting Thompson in Louisville, Steadman sketched steadily. Thompson chastised him for that habit and for his grotesque illustrations, but he consistently maintained that Steadman’s work was better than the story he filed. Steadman also appeared in the story as Thompson’s wingman, which became a gonzo staple. Even before the piece was hailed as a breakthrough, Thompson proposed that they collaborate again.

Steadman’s most famous illustrations would appear in Rolling Stone, the San Francisco rock magazine founded after the Summer of Love. Yet his work bore little resemblance to hippie art, which reflected the advent of LSD and evoked a sense of “cosmic initiation.” Steadman had no interest in drugs or the occult, as such. For him, authority was the mask of violence, and satire was a form of retaliation. The mild-mannered Welshman used his drawings as a weapon, and like Thompson, he hit the mark by overshooting it.

Many of Thompson’s remarks about his illustrator applied equally well to himself. “Ralph sees through the glass very darkly,” Thompson said. “He doesn’t merely render a scene, he interprets it, from his own point of view.” He also described Steadman’s process. “Using a sort of venomous, satirical approach, he exaggerates the two or three things that horrify him in a scene or situation,” Thompson noted. “He gives me a perspective that I wouldn’t normally have because he’s shocked at things I tend to take for granted.”

Thompson began to seek out or create scenes that would alarm Steadman. “His best drawings come out of situations where he’s been most anguished,” Thompson said. “So I deliberately put him into shocking situations when I work with him.” As their partnership developed, Thompson also used Steadman’s work to stimulate this own. In these and other ways, Steadman figured in Thompson’s process and was an indispensable part of gonzo’s success.

The Thompson-Steadman Report

As soon as the Kentucky Derby piece appeared, Thompson began to receive congratulatory letters and calls. One of the letters was from Bill Cardoso of the Boston Globe, who described the piece as “totally Gonzo.” Thompson had heard Cardoso use that term during the 1968 New Hampshire primary, and he began to apply it to his own work.

Writing to Hinckle in July 1970, Thompson proposed a series of articles in the style of the Kentucky Derby piece. He and Steadman would cover the Super Bowl, Mardi Gras, America’s Cup, and other spectacles. The idea, he explained to Steadman, would be to “rape them all, quite systematically, and then we could sell it as a book: Amerikan Dreams.” The two men would “travel around the country and shit on everything.” Thompson considered the “Rape Series on Amerikan Institutions” a “king-bitch dog-fucker of an idea.” They would turn out articles “so weird & frightful as to stagger every mind in journalism.” But Scanlan’s was already struggling to survive, and it published its final issue in January 1971.

By that time, Thompson had struck up a correspondence with Jann Wenner, who invited him to contribute to Rolling Stone. In many ways, it was an odd match. Wenner often recruited fellow students from the University of California, Berkeley, where he wrote for the student newspaper and covered the Free Speech Movement. Ten years older than Wenner, Thompson was an Air Force veteran who started as a sportswriter and never earned a college degree. Having worked for Hinckle at Ramparts, however, Wenner was well aware of Hell’s Angels and thought Thompson’s material might click with his readers.

Thompson laid off the gonzo sauce in his first two Rolling Stone pieces, which included a long article about the Chicano movement in Los Angeles. In the middle of that research, he invited his source, Chicano attorney Oscar Acosta, to a Las Vegas motorcycle race that Sports Illustrated asked him to cover. When Thompson’s submission ran 10 times longer than desired, the editors rejected it. An irate Thompson decided to double down. He expanded the piece and sent it to Rolling Stone, which ran it with Steadman’s illustrations.

That story’s effect on Rolling Stone is difficult to exaggerate. Perhaps more than any other single work, “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” defined the magazine’s media niche. Always more than a rock magazine, Rolling Stone was later described as the voice of its generation, and Thompson became its most popular writer.

Although the Thompson-Steadman Report never came off at Scanlan’s, Thompson eventually produced “Fear and Loathing” in its image—and then continued to build the gonzo franchise at Rolling Stone.

Raoul Duke

As a branding tool, “gonzo journalism” served Thompson well, but the label masked one of his most significant achievements. Whenever necessary, he shrugged off the protocols of journalism, even the relatively elastic ones of New Journalism, to tap the power of fiction. “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” is a parade example, and Thompson’s decision to narrate it in the voice of Raoul Duke was the final piece of the gonzo puzzle.

The relationship between fiction and journalism was top of mind for Thompson. Neither mode, he declared, was necessarily truer than its counterpart. Both were arbitrary categories and different means to the same end. Moreover, he knew that even the most scrupulous reporting was never purely objective, if only because the elements of any story—selection, emphasis, tone, and diction—involved choices that were laden with value judgments. Any list of facts is a theory in the weak sense, the intellectuals tell us, but Thompson’s version was pithier. “Facts are lies when they’re added up,” he once told a senior editor.

Yet Thompson couldn’t fashion the blend of fiction and journalism he had in mind. Norman Mailer had shown the way in The Armies of the Night (1968), the novel whose protagonist was also named Mailer and which won the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize. Thompson likewise wanted to create a fictional character for his second book. That way, he explained to Silberman, he could use the Democratic National Convention or Nixon’s inauguration “as a framework for the trials and tribulations of my narrator, Raoul Duke.” His goal, he explained in a different letter, was “to let me sit back and play reasonable, while he freaks out. Or maybe those roles should be reversed … ?” Thompson couldn’t solve the riddle of the second book, which was already more than two years late.

In 1971, he realized that the Las Vegas story fit the bill. It began as a piece of experimental journalism, he claimed.

My idea was to buy a fat notebook and record the whole thing, as it happened, then send in the notebook for publication—without editing. That way, I felt, the eye & mind of the journalist would be functioning as a camera. The writing would be selective & necessarily interpretive—but once the image was written, the words would be final; in the same way that a Cartier-Bresson photograph is always (he says) the full-frame negative. No alterations in the darkroom, no cutting or cropping, no spotting … no editing.

That plan was too difficult to execute, and Thompson found himself “imposing an essentially fictional framework on what began as a piece of straight/crazy journalism.”

Unlike most of the copy Thompson submitted to Rolling Stone, “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” came in clean. Even so, editors grappled with it, checking facts and constructing timelines. As they did so, Thompson told Wenner that the piece required a different editorial approach. The problem, he said, was that Wenner was “working overtime to treat this thing as Straight or at least Responsible journalism.” He would be better off fact-checking a Bob Dylan song or Naked Lunch, Thompson said.

Thompson’s inner circle understood this part of his project. Novelist William Kennedy observed that Thompson seemed to be writing journalism but was actually developing his fictional oeuvre. Privately, Thompson told Tom Wolfe that narrating his story through a thinly veiled protagonist prevented the ‘‘grey little cocksuckers who run things’’ from ‘‘drawing that line between Journalism and Fiction.’’

Thompson later called Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas a “nonfiction novel,” which only deepened the generic ambiguity. Even Silberman had to ask whether it was fiction or nonfiction. The book is still classified as the latter, even though neither major character is a real person and the drug experiences are wildly exaggerated. Thompson and Acosta left Los Angeles with alcohol, marijuana, and prescription speed in the rental car, not the extravagant drug cache that Raoul Duke itemizes in the book’s opening pages. After reading the manuscript, Silberman said he didn’t believe that Thompson was actually tripping in Las Vegas. Thompson replied that his Rolling Stone colleagues credited the drug orgies, and that Silberman should keep his interpretation to himself.

A critical and commercial success, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was also a culmination. It reflected the original idea for the Thompson-Steadman Report and successfully blended fact and fiction. It also targeted the political class by casting Las Vegas as enemy territory. Duke notes that Nixon would have been the city’s perfect mayor, with John Mitchell as sheriff and Spiro Agnew as master of sewers.

Had Thompson written nothing else, gonzo journalism would have left its mark, but his next assignment expanded its domain. Covering the 1972 presidential campaign for Rolling Stone, Thompson produced a classic work of American political journalism. Mixing campaign news with astute media criticism, outrageous satire, and scorching invective, Thompson took his revenge on Muskie, Humphrey, and Nixon. He never bothered to disguise his support for George McGovern, the only major candidate who opposed the war, and though he also criticized the McGovern campaign, he was devastated by the Democrat’s defeat. Later, a McGovern strategist described Thompson’s work as the least factual and most accurate account of the race. It was a shrewd assessment of Thompson’s modus operandi as well as his achievement.

By the time Nixon resigned, Thompson’s style, persona, and model of authorship were set. As his prose became more fantastical, lunacy emerged as a central theme. Yet as novelist Nelson Algren remarked in 1979, Thompson’s “hallucinated vision strikes one as having been, after all, the sanest.” That vision was also prophetic; in 2016, political scientist Susan McWilliams argued that his work predicted Trumpism and its “ethic of total retaliation.”

Once gonzo journalism made Thompson famous, he was reluctant to leave it behind. Indeed, he dined out on it for decades, which made his achievement seem ineluctable. Yet the four steps outlined here involved struggle, risk, even trauma. Each was an improvisation, an experiment, and a step into the unknown. Too often dismissed as a party animal and put-down artist, Thompson was arguably the most distinctive American voice in the second half of the twentieth century, but any careful review of his career reveals the radical contingency of his signature style and body of work.

Portions of this essay appear in Peter Richardson’s Savage Journey: Hunter S. Thompson and the Weird Road to Gonzo, just out from University of California press, printed with permission.