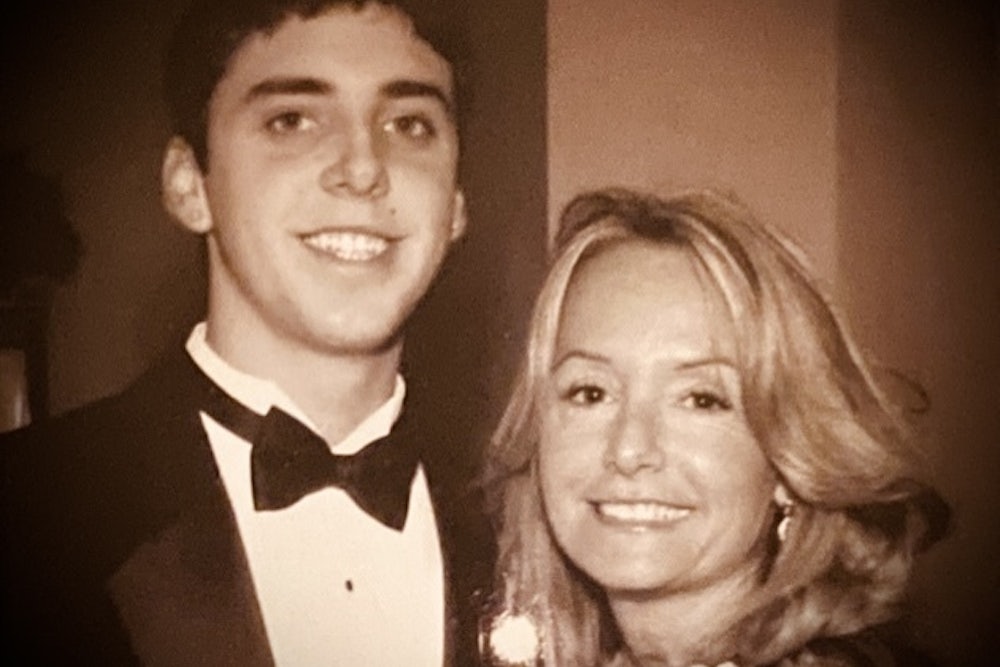

When Troy Howlett collapsed and died in his bedroom in Charles City, Virginia, on the morning of July 30, 2018, his mother, Donna Watson, was on vacation. It was a Monday, and 31-year-old Howlett was starting a new job that day. Watson, knowing her son was nervous about it, kept checking in, growing more worried as she got no response. Later that evening, having run out of reasons why her son wouldn’t or couldn’t call or text back, she asked a friend to look for him. When the friend found her son’s body, he told her it looked like his hands were locked in prayer.

Watson assumed her son died from a stroke or aneurysm possibly tied to his history of substance use. For 13 years, Howlett had struggled with an addiction resulting from a traumatic accident he suffered in high school. (Run over by a car, he became addicted to prescription pain pills. He did eight stints in rehab, Watson told me.) By the spring of 2018, Howlett was living with Watson and had been off drugs for close to six months, regaining some weight and doing well, she said. But one night, after meeting up with some old friends in Hopewell, a small, nearby town where Howlett was born and raised, the temptation grew too strong—Howlett relapsed and passed out behind the steering wheel of his parked station wagon, Watson told me. “People with substance-abuse issues—it’s so hard to be around that type of stuff and not do it,” Watson said. “So, he did that night.”

By the time Watson arrived at the emergency room, Howlett was awake and speaking with officers from the Hopewell Police Department. On probation at the time, with drug-related charges and another court date looming, Howlett was offered a choice by police officers, Watson remembers. He could either wait out his court date in jail or work with the police as a confidential drug informant. For Howlett, who was terrified of jail, there really was no choice, his mother told me. So he reluctantly agreed.

Working as an informant comes with great risk. Harmful and violent outcomes, including a violent retaliatory death (which Howlett feared, according to his mother) aren’t uncommon, despite assurances from law enforcement. The inherent secrecy of police investigations and a lack of uniform data collection make it hard to assess the true toll of informant work on people’s lives, but stories like Howlett’s do surface. The case of Rachel Hoffman, a young college student murdered in Florida while working as a drug informant, is likely the most cited instance of what can go wrong. But being found out and killed isn’t the only risk for informants with substance use disorder. As law enforcement around the country cracks down on an opioid and fentanyl epidemic of tragic proportions, informants who are users are particularly vulnerable. Working with police on drug cases puts them in a situation where relapse or deadly overdose is not just possible, but likely.

Luke William Hunt, a former FBI agent who’s now an assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Alabama, told me that given the tremendous amount of leverage police have over drug informants, it’s not always clear that informants have a “real choice” when it comes to working with police. “Many are not well-versed in what they’re getting themselves into, the legal ramifications, and also the potential risks that they’re going to be subjected to,” Hunt said.

One former informant in Hopewell, who spoke with me on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation, worked with the local police in hopes that the father of one of her children, who was awaiting trial, would receive a reduced sentence. “They came to me and said, ‘If you help us, we’ll help him,’” she recalled. “I didn’t want the father of my kid to be fucked up.”

At the time, she was pregnant with another child, and ended up working with detectives from the Hopewell Police Department—making controlled buys of heroin and crack cocaine—for less than a month. Having struggled with substance use disorder in the past, she was not using drugs before she was approached by police, she said. But while working as an informant, she relapsed, and was ultimately arrested on an unrelated charge. She was forced to give birth while shackled to a hospital bed, she said.

Five years later, she lives in continuous fear of the people she informed on. “I never saw anybody get locked up,” she said. And the father of her child, who she set out to help, is still incarcerated.

Even if a drug informant stands to gain from the arrangement, Hunt questions whether most of these leveraged bargains should even exist. “If you put someone in a situation where they have serious risk of hurting themselves through relapse or getting shot, or stabbed, or robbed—even if there’s a potential benefit for them and they’re willing to take that risk—that just doesn’t seem like the kind of thing we do, given basic commitments to the sanctity of life,” Hunt said.

The morning after Howlett died, Watson, back home, found a text message that had been sent to her son’s phone on the day he died. The message, which she shared with me, read: “I reached out to the CA just waiting on a reply.”

She knew her son had been making controlled buys of heroin, working directly with a detective from the Hopewell Police Department. Confident the message was from the detective—and that “CA” stood for the commonwealth attorney who she believed would have to sign off on her son’s informant work—Watson replied.

“This is troys mom,” she wrote. “Troy passed away yesterday. They dont know how yet. Thinking possibly a aneurysm, stroke, or maybe a seizure. He was so stressed about all this court mess.”

Watson received a response from the number within an hour.

“We are so sorry for your loss,” the message read. “We were doing everything in our power to help him get the court mess behind him. He was working extremely hard with us and we are so sad about this news.”

The Hopewell Police Department declined to comment.

But seven months later, Watson found out the true cause of her son’s death: an overdose. “It was like he died all over again,” Watson told me. According to his death certificate, Howlett died due to combined fentanyl, acetylfentanyl, and despropionylfentanyl toxicity. “He snorted it and it killed him,” Watson told me.

In 2020, Watson filed a pair of lawsuits asking for $13 million in damages. In the wrongful death complaint against the Hopewell Police Department, its retired police chief, two officers, and Hopewell Commonwealth’s Attorney Richard Newman, Watson alleges that the defendants made her son purchase drugs “with full knowledge” of his substance use disorder, which included the use of “opiates, including heroin and other illegal drugs.” (Newman did not respond to a request for comment.) She also claims that the defendants exposed him to illegal drugs that contained fentanyl, and that given the fact that her son had failed drug tests while working as an informant, Howlett must have been using some of the drugs that he was purchasing. (The second lawsuit was related to the arrest of Howlett’s best friend during her son’s funeral, which ruined the service, Watson said.)

In another series of text messages from Howlett’s phone that Watson shared with me, her son, in apparent desperation, asks not to have his bond revoked and says that he has more people he can inform on. A message sent back to his phone read, “Ok I will try!”

“Thank you and again I just slipped up I will not fail another drug test this was the first drug test I failed I just hope they can give me another chance and I promise I won’t feel another one [sic],” Howlett replied.

In November, Watson’s lawsuits were dismissed by the Circuit Court. Her attorney has filed a notice of appeal to the Supreme Court of Virginia.

While Watson has turned to the courts for restitution, she’s also looking to the Virginia state legislature. Some states have adopted legislation to address the problem of unreliability of informants and the wrongful convictions that often result from their misinformation, according to Alexandra Natapoff, a professor at Harvard Law School and author of Snitching: Criminal Informants and the Erosion of American Justice. “But those reforms tended not to address the problem of the use of informants who have substance use disorders,” Natapoff told me, “either from the perspective of innocent people who were convicted on that basis or from the perspective of the vulnerable informants themselves, who were often pressured into becoming informants at risk to themselves or risk to their recovery, or had their addiction worsen in their performance of their jobs.”

In recent years, the issue has gained more attention, and today, the “counterproductive injustice of pressuring people with substance use disorders into being informants to work off their drug charges in ways that threaten their sobriety” is more apparent to legislators, Natapoff believes. “Ten years ago, people were not engaged with that particular destructive aspect of drug enforcement,” she said.

Rachel Hoffman’s death in 2008 ultimately led to legislation, Rachel’s Law, that regulates how informants are recruited and handled in Florida; today, law enforcement agencies in Florida must have policies and procedures that consider a potential informant’s substance abuse or history of substance abuse when assessing their suitability for the work. In Minnesota, Matthew’s Law, which was adopted in 2021, will lead to the creation of a model policy that police departments and law enforcement agencies will use when working with informants. The bill, named after a man who overdosed on heroin that police ordered him to buy, places greater limits on the use of informants with substance use disorder—barring the use of informants that are receiving inpatient or outpatient treatment for substance abuse and those who have experienced an overdose within the past year. It would also require treatment and prevention referrals to informants with known substance-use issues. Mississippi and Pennsylvania have also enacted related legislation.

Watson shared with me a draft of a bill she hopes Virginia will adopt in 2022, which she believes will lead to more accountability and protection for informants like her son. The legislation would establish a model policy for the use of confidential drug informants and would require probation and parole officers be given notice of a parolee or probationer’s work as an informant. Additionally, no informant could work with police if they violated the terms of their parole. If adopted, commonwealth attorneys would also have to give formal approval, and no informant would be allowed to unlawfully use or possess any controlled substance. Watson has been working on the bill with Virginia House Delegate Rodney Willett and plans to testify before the legislature in 2022.

One of the “great sins” of the informant market is how it treats vulnerable people, Natapoff told me, noting the lack of a “protective ethos” not just for informants themselves, but also for victims of informants threatened by wrongful conviction. From informants with substance use disorder to immigrants, young people, and people struggling with mental health issues, “all these people are put at risk by the cavalier attitude towards informant safety,” she said.

Watson believes a “protective ethos” or established protocol may have saved her son and other informants like him. “These were the throwaways,” she said. “This is somebody that they couldn’t care less about. But what they didn’t know is: He was my baby.”