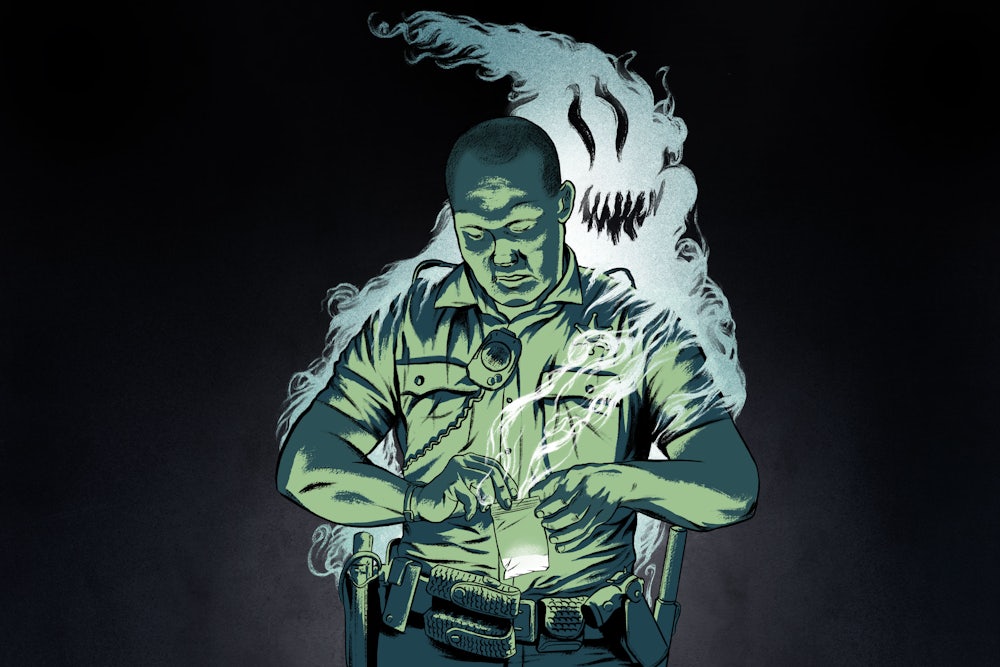

Can you overdose on fentanyl just from being near it? Over the past few years, a number of police officers have said that they O.D.’d merely from brief exposure to the drug. In 2016, the Drug Enforcement Administration even issued a warning to cops about the dangers of such encounters. The stories have made national news, but they’ve also invited skepticism. On Episode 35 of The Politics of Everything, hosts Laura Marsh and Alex Pareene discuss the phenomenon of cop overdoses with Dan McQuade, who wrote about it for Defector; Timothy McMahan King, the author of Addiction Nation, a book about the opioid crisis; and Patrick Blanchfield, who’s written about cop psychology and cop culture.

[News clip] An Ohio police officer is recovering tonight after he was nearly killed on the job. Police say the East Liverpool officer accidentally overdosed on fentanyl after he touched that dangerous drug.

Laura Marsh: This is from a 2017 news story about a police officer overdosing on fentanyl.

Alex Pareene: The odd thing is, touching the drug is all the officer did.

Laura: It’s not an isolated case. In the last few years, there have been several similar news stories. In each one, a police officer gets sick just from being in the same room as fentanyl—from touching it or from breathing the air around it.

Alex: In August, the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department issued a safety warning about the threat of accidental fentanyl overdoses. The video made national news.

Laura: It also drew a lot of skepticism. Are these kinds of overdoses even medically possible? And if they’re not, then what is happening?

Alex: Today on the show, we’re talking fentanyl, the war on drugs, and the psychology of American policing. I’m Alex Pareene.

Laura: And I’m Laura Marsh.

Alex: This is The Politics of Everything.

Alex: Our first guest is Dan McQuade, a writer at Defector Media. Dan wrote about that San Diego County Sheriff’s Department video. The video showed a patrol deputy having a very negative reaction to exposure to fentanyl. Dan, thanks so much for joining us today.

Dan McQuade: Of course, thanks for having me.

Alex: Can you tell us what happens in this video?

Dan: The video shows a patrol deputy, and I believe he was still in training. It’s his and mainly his corporal’s body cam footage. The deputy is lying flat on the ground; he appears as if he’s passed out. The corporal is administering Narcan—naloxone is the generic name for it.

Alex: What you would give to someone who had had an overdose.

Dan: Yes. It’s able to instantly reverse an opiate overdose. And they cut to footage of him in the ambulance taking him to the hospital.

[News clip] You OK? Talk to me. No, no—don’t be sorry. There’s nothing to be sorry about. I got you, OK? I’m not going to let you die.

Alex: The narrative of the video, then, is these sheriff’s deputies were exposed to fentanyl in the course of their job. And this is the dramatic, produced video about how the deputy overdosed from that exposure and had to be rushed to the hospital. And it is meant to highlight the dangers that these police officers face every day in their fight in the war on drugs. Is that a fair way to describe the thrust of it?

Dan: That is the crux of the video. It’s a bit of propaganda-slash-PSA—the video was titled “The Dangers of Fentanyl.”

Laura: So this video came from the San Diego Sheriff’s Department, and it did a very successful job of getting their narrative out there, which is that fentanyl overdoses just from exposure are dangerous to police. Is this a narrative that’s coming out of the San Diego Sheriff’s Department alone, or is there a broader narrative from other police departments about this phenomenon?

Dan: This has been a story for, I would say, about five years now. The sort of Patient Zero for this thing came in 2016, when the [Drug Enforcement Administration] released an alert to law enforcement.

[News clip] I’m Jack Riley, and I’m the deputy director of the DEA. I want to take a minute today to talk to you about something very important. As a matter of fact, it could kill you. And that’s fentanyl.

Dan: It was similar to the San Diego thing—not as slickly produced, but it talked with some law enforcement officers in Atlantic County, New Jersey, and they talked about how they had come into contact with fentanyl and said that they had suffered an overdose.

[News clip] That’s what my body felt like. If I could imagine or describe a situation where your body is completely shutting down and preparing to stop living, that’s the feeling I felt.

Dan: This communication from the DEA not only made the press, but it made its way into law enforcement circles. People shared this information. And so then there would be news stories about an officer, usually a narcotics cop, who was processing drugs or processing an arrest and touched fentanyl or came into contact with fentanyl in some way, and had overdosed and had to be either revived with Narcan or taken to the hospital.

Alex: You have held fentanyl, you have been near fentanyl, you have been exposed to it with skin contact, I believe. Did you have to be hospitalized?

Dan: No, I did not. I have touched plenty of different drugs, but it simply doesn’t work this way. I mean, it makes sense: If it were skin-soluble, why would people take the time to shoot up? If it were that strong, you wouldn’t need to put the drug into a vein of your body in order to get a euphoric high. People seem to treat it as if it’s a poison in a movie or something.

Alex: Radioactive or—

Dan: Something that you could just touch and it would kill you. But the truth is that it has to be consumed in some other way in order to achieve its desired effect of getting you high. So that’s why you would need to smoke it or inject it, which is probably the most common form.

Laura: One thing I want to clarify is that there is such a thing as a fentanyl patch. So there is a version of fentanyl that you can apply to the skin and it can deliver the drug. So some people who hear about police overdosing from touching it might think, “Oh, well, maybe it can work that way.” What’s the difference?

Dan: So there’s two things to talk about here. There is medical fentanyl. There is fentanyl that is used in surgeries or in patches, mainly for pain relief. But this fentanyl is not what is getting out in the drug supply. The drug supply is almost all illicitly manufactured fentanyl.

Laura: What form is that usually available in?

Dan: A powder, or it can be pressed into a pill, or it can be a liquid.

Laura: So it would never look like a patch.

Dan: People do use fentanyl patches recreationally, but they may just put them on, or people sometimes lick them. But the way a fentanyl patch works is that it releases the drug slowly into your bloodstream. So you don’t get an instant high from a fentanyl patch unless you do something else to it. It is skin-soluble, but there’s a specially designed polymer in the patch that sends it into your bloodstream. It’s not something you would find in the recreational drug supply.

Alex: We should explain how you have come to hold it and have come to know how people use it, and that’s from your volunteer work.

Dan: For over a year, I’ve been a volunteer at Prevention Point Philadelphia, which is a needle exchange and social services provider in the Kensington section of the city. I want to make clear that I’m not a first responder—I’m not a medic.

Alex: But you’ve seen someone experiencing a fentanyl overdose.

Dan: I can’t even tell you how many times I’ve seen it.

Alex: Does it look like what happened to that deputy in that video?

Dan: Not really. If I’m using the National Harm Reduction Coalition’s signs of an overdose, some of it fits—loss of consciousness, breath slow and shallow and erratic. But the one thing that I would say is the most noticeable feature of an overdose is that the skin turns bluish-purple, if you’re white, and if you are a darker-skinned person, it turns ashen, and that did not appear to be present in the video of the San Diego officer overdosing. But I didn’t really need to see the video to know that it was not an overdose. Police officers are worried about touching fentanyl and overdosing, and they’re having panic attacks as a result. Some people who don’t believe this video think it’s intentional—

Alex: Like an intentional fake.

Dan: Yeah, and I don’t think it is. If a police officer is using opiates on the job, they’re likely to get arrested for it, and it’ll make the news that these officers are using on the job. But these officers were legitimately having panic attacks because they think they can overdose by touching fentanyl.

Alex: You referred to the euphoric high you get from it. And none of these police officers are experiencing the reason people do the drug in first place.

Dan: A man who I talked to for my article, Douglas Hexel, is a firefighter in New York who runs a company called Rescue Med NY that runs seminars for first responders and teaches them the actual dangers of being around drugs, but basically what it seems like he does is try to stop first responders from having panic attacks on the job because of this misinformation. He is the one who told me that no one he’d ever talked to has said that they’ve had a euphoric high before experiencing it.

Alex: Right. If it were an actual overdose, you’d get high first.

Laura: So it seems that in the video, there is something happening that, in your opinion, is likely a panic attack. I’m trying to figure out what is at stake in the video presenting the panic attack as a fentanyl overdose. What are the real world consequences for that being the narrative that’s out there, this idea that cops can overdose just from touching or being near fentanyl?

Dan: I would say the main danger from that is to drug users. They know that that isn’t how it works. But if someone overdoses, a nearby stranger, maybe even a first responder, may be like, “Oh, well, I don’t want to get too close or else I might suffer this contact high as well.” And so I would say, people may be less likely to help out if they are worried about themselves suddenly suffering an overdose.

Laura: Do you know of any cases in which drug users have been prosecuted for exposing police to fentanyl?

Dan: In 2018, a man in Ohio pleaded guilty to assault on a police officer after fentanyl powder fell onto, I believe, the police officer’s shirt. And then the officer had what was most likely a panic attack. He pleaded guilty to assault and drug charges and spent six years in prison. That officer, Chris Green, was fired last June for, I’m reading here, more than two dozen violations of the policy manual, including dishonesty, discourteous treatment of the public, and gross misconduct. I like the phrase “discourteous treatment of the public.”

Alex: I didn’t realize a cop could be fired for that.

Dan: He of course denies the allegations.

Laura: Wow—the consequences of this really can be incredibly steep for people who are using drugs, facing inflated penalties. I mean, in this case, this is someone going to prison for assault for an action that most people would not recognize as assault.

Dan: I mean, he probably was guilty of the drug charges, if they found him in possession of fentanyl, but otherwise it does not seem to make any sense.

Laura: Thanks so much, Dan.

Dan: Thank you.

Alex: I think we’ve established that while something is going on with these police officers, it’s almost definitely not a fentanyl overdose.

Laura: Misidentifying what’s going on with these offices has some real costs.

Alex: But fentanyl overdoses are a huge problem. After a short break, we’ll talk with Timothy McMahan King, who wrote a book about the opioid crisis. He says the way we’re trying to fight that crisis is just making it worse.

Alex: Before the break, we were talking about these reported overdoses. But why fentanyl? Why aren’t we hearing about police overdoses from exposure to other drugs?

Laura: We’re joined now by Timothy McMahan King, who’s written about the opioid crisis. Tim, why do you think we keep hearing about reported fentanyl overdoses? Police come into contact with a whole range of drugs. What’s different about fentanyl?

Timothy McMahan King: Well, for a lot of folks, this feels like it came out of nowhere. Twenty years ago, it was incredibly rare to hear about a fentanyl-related overdose. In fact, it was probably around 1,000 people a year. In 2020, we hit 57,000 overdoses related to fentanyl. And so this will sound scary to folks, especially in the midst of a viral pandemic. People have heard for years now about the opioid epidemic—it sounds like this drug is evolving in a way that it is getting deadlier and spreading. But there are some important distinctions, because fentanyl isn’t a virus, it doesn’t evolve. And in fact, the reason we are seeing an uptick in fentanyl across the country—there’s a pretty simple explanation, even if it’s counterintuitive, and that is federal drug policy. It is often referred to as the iron law of prohibition. People who had been using prescription opioids when the federal government cracked down on that, it didn’t stop the problem, it moved people to street heroin. And when smugglers were bringing in street heroin, what did they do? They were motivated to use a more potent synthetic opioid, fentanyl. And so now that’s why we see it across the country: It’s a natural result of these market forces that we’ve seen before and we’re seeing play out now with deadly consequences.

Laura: So just to make sure I’ve got that right: When we’re talking about prescription opioids, you’re talking about something like Oxycontin, which is the drug produced by Purdue Pharma, the Sackler family, which has faced very high-profile litigation, for all the harm that has done to people who ended up getting addicted to it and overdosing on it. And I think most people seeing that prosecution would think, this is a really good thing—this company that was pushing this drug onto people is facing consequences. And it sounds like what you’re talking about is an unintended consequence of Oxycontin and drugs like Oxycontin being pulled back: It has meant that the other drug to go to is now fentanyl, which is even more dangerous.

Timothy: Absolutely. And I have no love for Big Pharma, and I have no love for the Sacklers: I’m fine with them being punished. But the problem is, it’s taken us away from the true culprit. I used to think of the war on drugs as like showing up to a big fire with a squirt gun—it just wasn’t a very effective approach. And now I see the war on drugs as showing up to a grease fire with a fire hose and actively making the problem worse. That’s what these policies have done. We are seeing people die as a result of federal policy. So I’m an expecting parent, and we just went through a class learning about what to expect, and the hospital had to dedicate an entire section on fentanyl because people are freaking out about the drug,

Alex: It’s so common in hospitals, right?

Timothy: Exactly. And in fact it is now one of the most common opioids used for pain relief during labor, because it has been shown to have the least amount of side effects. So what we use intentionally in a hospital setting because it is so unlikely to have problems, when it’s on the street and people don’t know the dosage, they aren’t educated on how to use it and how it might interact with other drugs, like alcohol. And it could be potentially contaminated because there’s a big difference between pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl and fentanyl that you’re getting on the streets. They are two different beasts. One is safe when used properly, and the other is what’s driving these deaths across the country.

Alex: That makes me want to ask the most basic question of all: What is fentanyl? It’s an opiate, and it’s common in hospitals. How is it common in hospitals and also the most dangerous street drug? How is it both of those things?

Timothy: Fentanyl was synthesized first in the 1960s. Most of our opioids come from an opium poppy base. And so we first had opium usage, then that was refined into morphine. Morphine was further refined into diacetyl morphine, which is now commonly known as heroin, and we have a whole bunch of these different drugs that are derived from the natural opium poppy. Now of course, that’s fairly expensive, because you have to rely on raising a crop and then processing that crop and then turning it into the chemical you’re looking for. And so, of course, scientists were looking for a way of synthesizing this with other base chemicals that don’t require the opium poppy, and that was successful in the creation of fentanyl. If you’ve ever had full general anesthesia, chances are you were under the influence of fentanyl for a short period of time, because it is such a potent but relatively short-acting opioid. Most people who are using drugs didn’t have any interest in fentanyl because it’s harder to know how much you’re taking. And then people know that’s more dangerous. Heroin was the drug that people were looking for. Slowly, the supply became heroin laced with fentanyl and then fentanyl replaced it entirely. And so as that shift has happened, we see these deaths skyrocket, and it is a predictable outcome of prohibition.

Alex: I remember reading some Village Voice story, probably 20 years ago, about how heroin would not be causing so many deaths if it wasn’t laced with so many things. And that made it seem to me that from a harm reduction sense, as you say, everything we’re doing to fix the problem of overdoses is not helping, because nothing that we are doing policy-wise is making it more likely that your heroin is pure. Maybe that sounds like a perverse thing to want, but if we want people to stay alive, we don’t want them taking an unknown amount of fentanyl.

Timothy: This is the big question: Is our goal [keeping] people alive and healthy, or is it fighting a particular substance? I was hospitalized for several months. I was in the [intensive care unit]. My parents were called in to come and say goodbye because the doctors thought they were going to lose me. And over time I was put on heavy doses of opioids, including both fentanyl and Dilaudid. When I was sent home, what happened next was not inevitable but not uncommon: I developed a substance use disorder and I had free access to heavy doses of fentanyl and Dilaudid—Dilaudid is another opioid that’s typically considered about 10 times more potent than heroin—and so even when I was using way off-script, my chances of overdose were next to nothing because I knew how much I was taking and it was pure, and I knew not to mix it with any other drugs. But what happened next is not what happens for most people. My doctor saw what was happening with my prescriptions, that they were running out faster and faster, and he sat me down, and he said, Tim, I want you to know you’re addicted to your pain medicine. My immediate reaction was to fight with him and to say, no, I’m actually still in pain, which I was, but then he completely disarmed me by saying, “But you didn’t do anything wrong. And I’m not going to take your pain medicine away from you when you need it, if you’ll be willing to take less over time.” And we made that deal with each other that day, and over time, and with some cognitive behavioral therapy, I was able to step down from the opioids, deal with my substance use disorder, and go back to work and go on living my life—while I had access to a safe supply of the drug that I was addicted to. That is so counterintuitive for most people who think that this drug is inherently evil, or who think that you need to go abstinent all at once. That is the path for some people, but that’s not the case for a lot of folks, and that wasn’t the case for me, and what shocks me, and what I didn’t know at the time and learned years later is that what my doctor did was likely illegal. He could have been criminally held accountable if it had been found out that he recognized that I had a substance use disorder and continued to prescribe me that medication. And yet it is actually one of the most effective ways to help keep someone like me alive and healthy until they find that path to some sort of stability in their life.

Alex: We treat very few people who are using illicit drugs that way, but it does seem like it would be more effective. Why can’t the war on drugs as a policy, as a government policy or a state action, why can’t they get themselves to something closer to that approach?

Timothy: I think one of the key things that we’re facing is misunderstanding about what drugs are and stigma around the people who use them. There is a belief that there are certain substances that are inherently evil and degrade your moral character, and that if you use them even once, they are then the direct cause of addiction. Each one of those statements is false. As long as we believe that drugs are inherently evil, then people will continue to support a war. But we’ve seen other countries take a different route. We saw Portugal completely decriminalize all drugs and start spending more money on treatment and support for people who use drugs than they did for enforcement. And we’ve seen Switzerland now for over 20 years have an effective heroin-assisted treatment. That means that if you have a substance use disorder and you’ve tried other kinds of recovery and it hasn’t worked for you, you can show up and get free heroin twice a day at a government-run clinic. And the success rates have been so much better than what we were seeing in the United States. If there was ever a serious push in the United States to move from our current illicit market to actually having a regulated market where people had access to a drug that they were addicted to in a safe way, I think the biggest opposition we’d see globally are the heads of cartels, because it would put them out of business. And that’s what happened in Switzerland—the illicit drug market by and large dried up. Other countries have done it. We need the political will to do it too.

Alex: Apart from ending the drug war, what do you, as someone who is on the other side of addiction, think we should actually be doing to prevent people from dying of fentanyl overdose?

Timothy: I think everyone should have access to what I had access to, and that is a safer supply in a regulated way that is able to keep them alive. And we also need to decriminalize possession. There is one important piece of legislation that’s before Congress right now, the Stop Fentanyl Act. That is a piece of legislation that could take immediate steps forward. And I think there would be the political will to pass something like it. Unfortunately, the Biden administration have said that they were against the war on drugs, and have now come in and said, “Long live the war on drugs, but now this is the new fall 2020 edition.” It’s a different version of the same mistaken mentality. The White House just recommended to Congress to extend what they call the fentanyl analog classification, to make sure that fentanyl and fentanyl-like substances are Schedule I, which increases criminal penalties for anyone caught with them or distributing them. It had been temporary scheduling before, and 70 percent of the people who’d been sentenced under that are people of color. So once again, we are seeing racism inside of the system targeting people who are Black and brown, when we aren’t doing anything to solve the problem.

Alex: Tim, thank you so much for joining us today.

Laura: Thank you.

Timothy: Thank you all for having me.

Laura: So it makes sense that fentanyl is at the center of these police overdoses, because it’s been portrayed as so uniquely dangerous, and because there’s more of it around now than there has been before. But the other piece of this story is the police, and the way that the officers in these reports specifically react to being around fentanyl.

Alex: After a short break, we’re talking to Patrick Blanchfield, who’s written about police psychology and police culture. We’re going to ask him how police are trained to approach fentanyl and what the supposed overdoses tell us about the legitimacy of American policing.

Alex: Patrick Blanchfield is a writer who has studied psychoanalytic theory and clinical practice. He writes frequently about the police. Last year he wrote a feature on “coptalk” for The New Republic. Hey, Patrick. Thanks for joining us again.

Patrick: Thanks so much. It’s a pleasure to see you all.

Alex: So I think we have established that we are not witnessing a fentanyl overdose in these videos. What do you think is causing cops to act like this?

Patrick: OK, so caveat, up front: I’m not a medical doctor. I’m not that kind of doctor. But when I see something like that, it looks like he’s having a panic attack of some kind—you can’t breathe, you seize up—but it’s a little more florid. And at that point, I think we could start using what medical and mental health professionals or the DSM call a conversion disorder, or a somatoform conversion disorder, which is the contemporary name for what was sometimes called hysteria or a hysterical fit. I think that’s the lens to look at this, both as an individual phenomenon and as exposing some stuff about policing—this is a symptomatic crisis within that.

Laura: In our episode on Havana syndrome we talked a little bit, actually, about conversion disorder. How would you define it?

Patrick: The contemporary definition of a conversion would be neurological symptoms with no clear neurological cause. People are probably familiar with what in the nineteenth century or early twentieth century was called hysteria. And in the case of classical hysteria, a lot of those symptoms would present as temporary paralysis. People’s limbs would lock up. They would start screaming, wailing, no apparent reason. And just to stipulate, hysteria in this sense never went away.

Alex: From a modern perspective, it sounds quaint. But it didn’t go away.

Patrick: It’s estimated that 10 to 15 percent of people who will show up in a modern neurologist’s office will be having some type of conversion disorder. They’ll have strange lethargy or fits of paralysis, etc., for which there isn’t a clear organic cause, even when we throw MRIs and so on at it. What is interesting is to think about the individual symptoms of a conversion disorder—they’re not just symptoms of the individual, they express symptoms of the society and specifically symptoms that have a lot to do with collective fantasies, fears, anxieties but above all, with certain types of social contradictions that will put people in positions of, well, breaking down and expressing those symptoms symbolically. The symptom reflects something.

Laura: You’re saying basically that conversion disorder is a simple example of, if someone is feeling intense stress, it manifests with physical symptoms. And so if we’re looking at police, what is the focus of that stress?

Patrick: If you’ll forgive me, I want to make one more caveat here: None of what I’m saying, and I think anyone who studies this will say the same thing, when we talk about a conversion disorder, it’s not the same thing as saying people are pretending. That suffering is real. When it comes to police, I think the police embody and enforce a whole series of contradictions involving power, involving vulnerability, involving social-ideological things, above all the good guy/bad guy dichotomy and maintaining the boundary that is the blue line. And when your whole job is maintaining boundaries, but also those boundaries are unstable and full of contradictions, it’s probably not surprising that people develop conversion disorders and contagion fears specifically, that they seize up or act out.

Alex: Maybe it’s an obvious contradiction, but police are both encouraged to act as superhuman warriors and constantly encouraged to feel under siege and feel vulnerable—that’s just part of the training. And it’s part of the entire atmosphere of policing—both strength and this constant existential threat.

Patrick: I don’t know if anyone has seen the Netflix documentary Flint Town. It’s a project where a bunch of filmmakers follow people in the Flint police department. It’s a lot of shadowing cops as they walk around. But there’s one particular scene that I think gets at all this. This is right after there were those Dallas sniper attacks, and a bunch of police officers in Flint get a briefing, and their police chief or whoever was in charge tells them, “You gotta go out there with a full day’s worth of ammunition and food, because you could be held down in a gunfight with a sniper for 24 hours.” One of these cops is driving around, a cop who incidentally, you later learn, has at least one use-of-force with a fatality on his record. He’s talking, directly looking into the camera, about the stresses of the job, about how it’s all politicized, about how when there’s a new mayor, you could get fired, about how a new chief could decide that you don’t need to work their shift anymore, about how you could lose your insurance, etc., etc. And then it seamlessly blends into his talking about how anyone on the street corner could possibly kill them or how you can get murdered anytime you pull someone over. In other words, there’s this whole slippage or fluidity between what’s perceived to be employment precarity and threats from violent others in the streets. And they bleed into one another while this cop who, again, mind you, has killed someone and gotten away with it, is scanning the street corners in this mode of hypervigilance.

Laura: So what you’re describing there is this individual enumerating fears and then acting on them, and that’s a personal response that lots of people have, but is there also training the cops are being given, about, for instance, the warrior cop mentality? Can you tell us what that is and what it teaches?

Patrick: There is a whole bunch of training on this. It’s not just a culture of them feeling precarious. If you go to a police academy, and lots of people have written about this, you’re going to watch a lot of videos of cops getting killed.

Alex: Ambushed.

Patrick: You’re going to hear everyone tell you, well, within that moment where you’re walking up to serve someone a ticket, they can shoot you through their door with a high-powered rifle that you never saw. Any given encounter could be lethal. Again, talk about contradictions that are kind of impossible: You’re supposed to treat the community with dignity, courtesy, and respect, but also they’re going to constantly kill you. It’s this odd contradiction of, “Be hypervigilant, and assert control at all times,” but also, “Treat people with human dignity and respect.” I’m honestly surprised that more cops don’t have panic attacks on the shifts.

Alex: I think that really interesting dichotomy that you described so well of, “This community wants you dead, and your job is to serve it”—I see that dichotomy if you follow the official police precinct Twitter, and then you follow the police union Twitter. The official police precinct Twitter will be like, “We’re playing basketball with the teams today.” And then the police union Twitter will be like, “This monster was let out on bail after stepping on an officer, we have to get this guy off the streets.” That’s sort of it, right?

Patrick: It’s untenable. Look, holding two contradictory thoughts in your head is a sign of being an intelligent person, or a normal one. But holding two fundamentally opposed moral imperatives while walking around with a gun in a job that one way or another steadily degrades your humanity—that’s going to have a different cash-out. The output there is not just mild hypocrisy or contradiction, it’s dead people. This is why I think the hysteria example is really helpful. Because one thing hysteria is all about, historically speaking, is expressing in the symptoms certain dynamics of power. You have these police literally seizing up, and they’re doing it as an expression, on the one hand, of their fear of the people that they’re supposed to be protecting. But it’s also a message to the public in general, not necessarily consciously, of, “Look at all I’m doing for you, look how much I suffer. I face things that can kill me that you couldn’t possibly believe. I could literally sniff some fentanyl from like a block away and die. How dare you question anything I do?” The police officer, who is feeling embattled for political reasons, somehow gains more power by face-planting on the sidewalk because of a fentanyl overdose. A certain performance of vulnerability becomes a way of asserting a new type of power or doubling down on a new type of power.

Alex: The audience for that stuff—it’s not the people being most policed.

Patrick: I don’t think it’s coincidence, or it feels like a haunting uncanny repetition, that the symptom that all these cops describe when it comes to their fentanyl, quote-unquote, overdoses is that they can’t breathe. The people, the agents of the state, the violence workers who have been in the figurative but not literal cross hairs with the public because they choked the life out of a man on camera as he screamed he can’t breathe—now they can’t breathe too. It really inverts the power dynamic in a bid for public sympathy. And the deference that that generates is enormous. But again, what this actually generates is an actual body count of people who are not being treated for actual opiate-use disorders. How many cops go into encounters with desperate people who they already find physically repellant, and now have yet another reason to think that simply, quote-unquote, doing their job can kill them? And that’s a fantasy. It’s not even that there’s a bad guy out there. It’s that simply being near this horrible contagious stuff can kill you.

Laura: When Alex and I were talking about this episode, he mentioned a couple of similar stories about police believing that they had been the subject of very subtle attacks from members of the public. Alex, why don’t I let you describe them.

Alex: We were remembering the New York police who imagined that their Shake Shack milkshakes had been poisoned, who went to the hospital over this imaginary poisoning and then defamed the manager of the Shake Shack. That was fake. The police officer who imagined that someone at the Starbucks had put a tampon in their coffee, which turned out to be a napkin that had accidentally fallen in the coffee. Then there was the police officer who completely fell apart in a front-facing video in their car because her Egg McMuffin was running late. Most of this was last year, and it feels like there was an obvious reason for that. To my mind, it’s that already existing fear of the public that we’ve been talking about, and also a feeling of a loss of public legitimacy that they found really stressing. What do you think?

Patrick: I think that’s exactly it. And social media virality has really upped the field of possibilities—to the point at which two cops, after a week of eating takeout, they’re finally feeling sick together, ergo they must be being poisoned.

Alex: That’s my favorite part of it. “We felt sick because for lunch, we had milkshakes and Shake Shack and then we felt gross.” Like, something must be not on the level here.

Patrick: It’s absurd. But I do think that there is something going on. It’s hard to imagine an institution that’s more insulated from public accountability than the police in American society. And I think on some level, the police are—not consciously, but on the level of vibes—aware of these contradictions. The gap between their protection and lack of accountability and their illegitimacy and the obviousness of how beyond the pale a lot of their actions are, I think that’s a contradiction, again, that’s very hard to live day to day. And so of course there is strange acting out. In the past year, it almost seems like a lot of their behavior in public has been about almost daring people to call them on this. Think about the amount of people who were beaten on camera at protests against police brutality—it’s this kind of brinkmanship, where it’s like, “You can’t get rid of us. Who else will do the public beatings?”

Alex: As you say, they’re immune from democratic accountability. Look at what’s happening in Minneapolis right now—it has proven nearly impossible to democratically decide to replace an urban police department. The entire political machine is lining up to prevent voters from having the ability to choose to do that. And I think that goes to exactly what you say. The police are beyond democratic accountability, but the thing that makes them mad on a personal level is just that a lot of people don’t like them anymore. That’s why I like the Egg McMuffin anecdote in particular, or the Shake Shack one. They’re used to not only having a pension and incredible job security, they’re also used to double-parking their car and getting their burger for free. And now they’re worried that when they do that, someone’s going to put something in the burger. That’s the fear they’re operating with.

Patrick: And in terms of where this is going in general—I mean, I don’t know what the next step is. Are we going to have police, like, reacting to Havana devices that are being deployed against them? Like they were assaulted by a Soviet vibe canon? Again, it points to these basic contradictions, and a lot of people don’t want to have to deal with it, because they are properly terrifying. If everyone were to think through the fact that every police officer you see could probably get away with summarily killing you, I think a lot of civilians would be planking and having hysterical fits in the streets. But there’s something about the fact that, well, we don’t get to do that—because they’re doing it for us. They’re already out there ahead of us. We can’t have a sustained conversation about qualified immunity or, say, disarming the police, because we need to be dealing with the fact that they’re being insulted by low-wage workers. As opposed to questioning their honor and privileges and impunity, we have to deal with their demands to be loved. And that, again, points to how this is about a broader social pathology. This class of workers should not exist in its current incarnation. Yet we apparently need them, and we apparently are tethered to continually imagining their existence—either people are held hostage by it or we’re more scared of the alternative.

Alex: Well, thank you so much, Patrick.

Patrick: It was so good to talk with you.

Laura: Patrick Blanchfield is the author of Gunpowder: The Structure of American Violence.

Alex: Timothy McMahan King is the author of Addiction Nation: What the Overdose Crisis Reveals About Us.

Laura: Dan McQuade is the video and multimedia editor for Defector, an employee-owned sports and culture website.

Alex: The Politics of Everything is co-produced by Talkhouse.

Laura: Emily Cooke is our executive producer.

Alex: Melissa Kaplan is our audio editor.

Laura: If you enjoy The Politics of Everything and want to help support the show, please go to wherever you get your podcasts and rate or review us. Every review helps.

Alex: As always, thanks for listening.