For as long as there have been police, there have been bestselling police biographies and autobiographies. In nineteenth-century Britain and France, bourgeois readers devoured police “memoirs” that peddled lurid glimpses into high-profile murders and tawdry street crimes alike. In the United States, readers thrilled to dime-novel sheriffs lassoing rustlers on the range and broadside exploits of Allan Pinkerton and his agents, women included, smashing conspiracies of anarchists, communists, and “Molly Maguires.” In the twentieth century, memoirs bylined by everyone from the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover to the LAPD’s Daryl F. Gates sold widely and netted their authors serious money in the process. (Hoover laundered his royalties through a nonprofit and became rich.)

The reading public looked to these stories for an understanding of their changing world. From the saloons of the lawless frontier, to the warrens of industrializing cities, to the vacant lots and housing projects of contemporary urban ghettos, cop memoirs have promised insight into their eras’ spaces of disorder, as well as vignettes—titillating, tragic, and comic—of the unruly persons who populate them. Cop memoirs also promise character studies of the people who patrol such dangerous zones, learn their ways, and presumably gain some portable wisdom about society and human nature in the process. The question “Who Watches the Watchers?” has an obvious answer insofar as everyone, it seems, wants to know what makes cops tick, and to see the world that they see.

Of course, whether in the first person or otherwise, not all or even most of these police narratives were actually written by police themselves. Many were ghostwritten by journalists, whose symbiotic relationship with the police has always been something of an open secret. Journalists can become “so coppish themselves,” H.L. Mencken remarked in 1931, that they function as “police buffs,” “police enthusiasts,” and “police fans,” largely dependent on information from the authorities for their stories. Today, as in Mencken’s time, a great deal of crime “reporting” merely reproduces police press releases—and many long-form cop memoirs reproduce not only the stories about cops that audiences want to read, but the stories cops want to tell about themselves.

Rosa Brooks’s Tangled Up in Blue: Policing the American City promises without question to be the cop memoir for the late 2010s and early 2020s. An accomplished scholar, journalist, and author who has moved in the loftiest legal, nonprofit, and foreign policy circles, Brooks brings a distinctive perspective to the police memoir genre, which boasts few women’s voices to begin with. Her narrative is pitched directly at contemporary anxieties over police violence, and begins with consciousness of a widespread sentiment that American policing is broken, and no one knows if it can be “repaired.”

As an account of what policing can be like for police themselves, Tangled Up in Blue is singularly frank, and its depictions of the civilians who encounter police possess a rare mixture of empathy, self-consciousness, and well-hedged appeals to context. But Brooks’s book is also about more than just policing as an institution, or even her own experiences as a cop: It is a deeply personal family memoir, and a meditation on questions of race, class, gender, and family inheritances. Some readers may find it enthralling; others may find it distasteful. Whatever the case, it is certainly revealing, sometimes painfully so.

“I joined the DC Metropolitan Police Department Reserve Corps because it was there,” writes Brooks. “It was there, and I was curious.”

This is Brooks’s story in a nutshell, at least on the surface, related with characteristic confidence and candor. When the idea of becoming a cop first strikes her in 2011, Brooks is in her forties, with a degree from Harvard, a master’s in social anthropology from Oxford, and a juris doctor degree from Yale. As a scholar with “a long-standing interest in law’s troubled relationship with violence,” Brooks has traveled the globe working with prominent nonprofit human rights groups, has published extensively about security and international law, has tenure at Georgetown, and has worked for the U.S. government, first at the State Department and then as an Obama administration appointee in the Defense Department. It is in her final days at this latter position, during a mandatory H.R. event, that Brooks encounters a woman in her sixties who discloses that, in addition to running implicit bias trainings, she serves as a reserve officer for the Washington Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). “People think I should be knitting,” says the trainer. “But let me tell you, putting them in cuffs dispels their stereotypes really fast.”

Brooks’s curiosity is piqued. As she learns, D.C. is one of the few major American cities where volunteers can receive much the same training as full-time police cadets and then become sworn officers of the law, required to patrol 24 hours per month, armed and empowered to make arrests. The idea of becoming a reserve officer comes to tantalize Brooks, even as she questions her own abilities and her motives. Can she make the time for classes, and could she even handle the training? Is the very idea just a midlife crisis? Her questions multiply, and both her ambivalence and hunger for the experience grow apace as high-profile episodes of police violence and mass unrest dominate headlines. “I doubted I could justify such a mad scheme to my colleagues, friends, and family members.” They mostly consider the U.S. criminal justice system “harsh, unjust, and biased.” (“The police are killing black people,” one of her Black colleagues tells her. “I can’t even talk about it right now.”) But Brooks remains fascinated by the workings of what seems to her an “impossible” job, and in the end curiosity and drive win out. “I was restless, and not quite ready to subside into tenured comfort.” And so in 2015 Brooks applies to the MPD Reserve program, and is accepted.

Brooks insists from the outset that her initial plan did not involve writing a book, or even doing “research” per se. To be sure, she invokes the idea of anthropologists doing “participant observation,” and has a unique familiarity with the practice of “immersion journalism” (more on this in a bit). But first and foremost, Brooks stresses, the purpose of her foray into policing was to see what policing was really all about firsthand. Indeed, she says she is halfway through her training before she decides to write anything. Even then, she also insists that her book is not to be read as a scholarly intervention, nor as offering policy prescriptions. Her goal, instead, is simply to “offer some stories” from her “own messy, complicated experiences.” Tangled Up in Blue, in other words, is at once constrained yet layered in its focus: It is a story about policing made up of stories of policing, collected by someone who came to policing as part of her own personal story.

As far as the promise of stories goes, Tangled Up in Blue delivers aplenty. Brooks is an excellent narrator with a keen eye for detail, and she embraces with gusto the access her new gig gives her. “Mostly, I’m just nosy,” she admits. “Sometimes I think that’s the whole truth of it. I liked having license to poke around in other people’s lives.” Whether it’s being “nosy” or unflinching, Brooks does not look away. Throughout, she is unsparing in her descriptions of how cops are trained, how they relate to one another, and what the job entails.

At the academy, Brooks tries to keep a low profile and “act like a model recruit”: “respectful, obedient, and dull.” Her reserve officer classmates are a group with a heavy representation of former military, law enforcement, and private contractors. They are overwhelmingly white; Brooks is one of only two women. She finds some of the officers solicitous and kind, others, not so much. She dubs one instructor “Lawsuit” for his nonstop, off-color patter and casual insensitivity. During firearms training, Brooks also witnesses an apparently unhinged cop manhandle and berate another student to the point of tears. When the student, a middle-aged Black woman, moves his arm off her body, he explodes: “You fucking touch me and I am going to fucking kill you!” Brooks privately expresses support to the woman, who promptly files a criminal complaint against the officer; during the investigation that follows, Brooks’s union rep unsubtly pressures her to downplay the incident (she refuses).

Brooks’s reflections on police training are astute. As she sees it, there is no real attention paid to making recruits consider what “good policing” might look like in the abstract, nor to formulating what its outcomes might be empirically in terms of crime rates, policing strategies, and the like. Nor still is there much consideration of history or the social forces that shape policing. All such big-picture concerns are sidelined in favor of a single-minded focus on tactics. “We had eight units on vehicular offenses and one unit on use-of-force policies—but nothing at all on race and policing,” observes Brooks. Above all, “the chief lesson learned at the academy was this: anyone can kill you at any time.”

Initiation into this worldview underwrites everything, making granular lessons taught to would-be cops into so many iterations of a basic imperative: Maximize control while minimizing risk. Police are thus primed for wary and antagonistic encounters with a public whom they are simultaneously told to dread as existential threats yet enjoined to treat with civility and “respect.” Police also quickly learn that their actions on the beat can lead to their being penalized, fired, or even prosecuted, and that, when push comes to shove, “the department would be only too happy to throw us under the bus.” Navigating the baked-in contradictions between “tactical officer safety dicta,” enforcing the letter of the law, keeping their jobs, and “serving the community” becomes not just a matter of officer discretion, but officer peril.

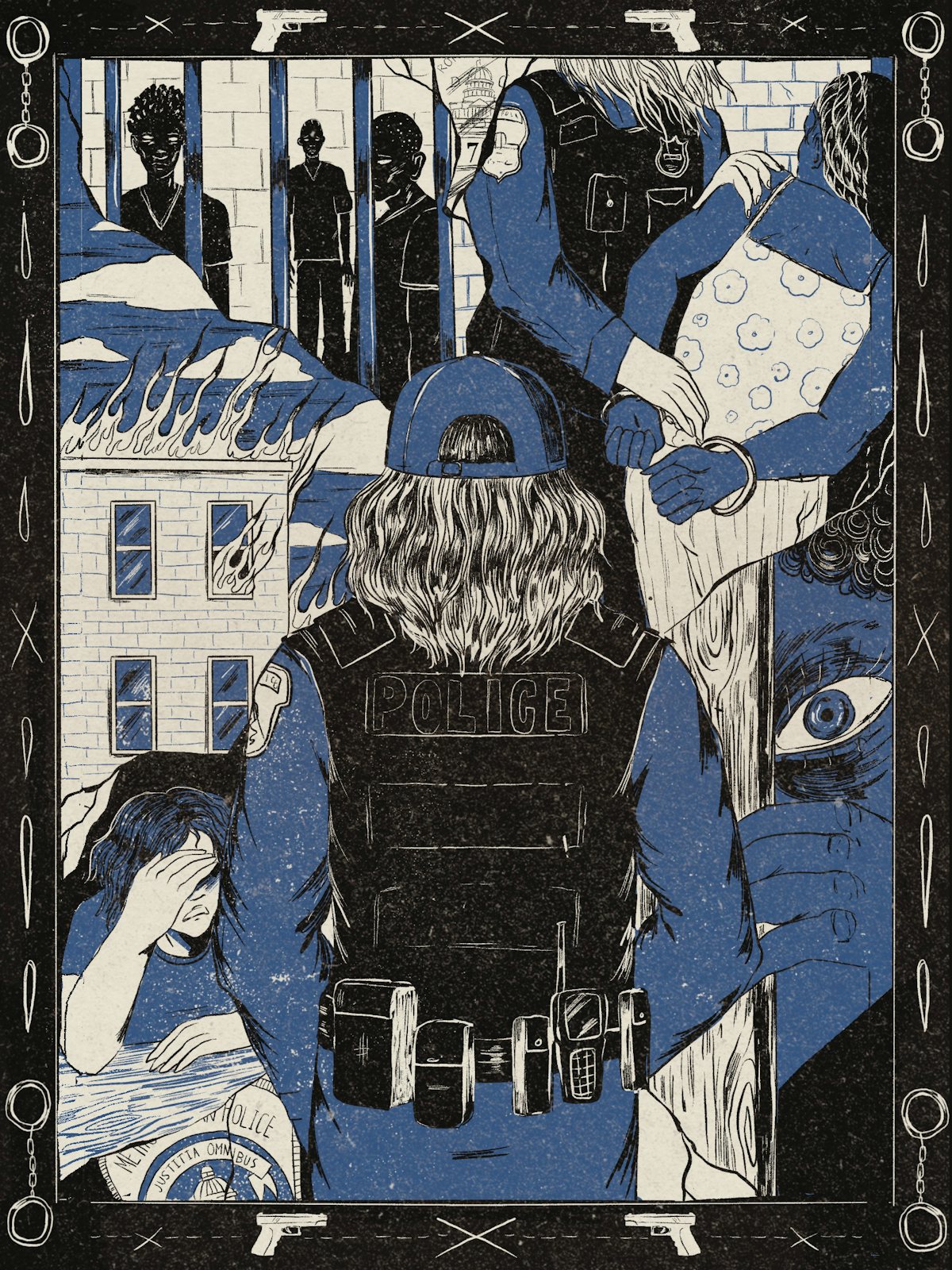

But as everyone knows, and Brooks takes pains to stipulate, the double binds officers face are only part of the equation: It is the people in the communities they police who truly live out (and sometimes die under) those contradictions. Even as Brooks gets into the technical details of police minutiae (“handcuffs are not as simple as they look on TV”), strikes wry notes (“Try searching a three-hundred-pound woman who bellows, ‘You’re tickling me!’ every time you come within six inches of her”), and relates comic scenes (getting trapped in a police station toilet while struggling with her gear), she is blunt: “policing in the United States is a breathtakingly violent enterprise,” and “if you are a police officer, sooner or later you will put another human being into a cage.” As Brooks nears graduation, and contemplates what comes next, she is compelled to acknowledge, “I was going to be putting someone in handcuffs at some point, and statistically, that ‘someone’ was likely to be poor and black. Statistically, I knew I was unlikely ever to fire my gun at another human being. I wasn’t even likely to use my baton or pepper spray. But it was now a genuine possibility.”

It is a possibility she accepts. Brooks graduates and chooses to work on patrol in MPD District 7D, Washington’s poorest.

“We got a lot of calls involving conflicts between mothers and daughters,” writes Brooks, well into her 18 months on patrol in 7D. “Or maybe it just seemed that way to me.” Throughout the book, Brooks reflects on these relationships, both as the mother of two daughters, and as a daughter herself. Brooks’s mother is none other than Barbara Ehrenreich, the socialist activist, feminist intellectual, and outsize luminary in the American leftist firmament. Among her dozen-plus books, Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America is a classic of immersion journalism, and saw Ehrenreich, a muckraker with a Ph.D. in biology, go undercover for three months struggling to get by on minimum wage in a variety of menial jobs. Both in form and in explicit content, Brooks’s book is, if not a rejoinder to her mother’s work, then a reckoning with her influence as a writer, intellectual, and parent. With its title borrowed from a Bob Dylan classic, Tangled Up in Blue is a deeply ambivalent, multigenerational family story.

Unsurprisingly, Ehrenreich is not pleased with her daughter’s new sideline. “The police are the enemy... they are not on our side,” she chides Brooks. Ehrenreich named her daughter after Rosa Parks and Rosa Luxemburg and is quick to remind her daughter that she was tear-gassed by cops at a protest while pregnant with her. “How do you rebel against a rebel?” wonders Brooks—and her stories of growing up in a household where “getting arrested by the Man was a privilege reserved for the grown-ups” make the question of what transgression and repression might look like in that context overdetermined indeed. Dragged to protest after protest, young Rosa grows increasingly resentful and exasperated. When her mother insists she boycott Nestlé chocolates, Brooks seethes, chafes, and finally capitalizes on a moment of distraction in a Scott’s Five and Dime to grab a Nestlé $100,000 Bar from the counter, run to a nearby alley, and scarf it down behind a dumpster. She leaves behind a quarter to pay for it first.

“So maybe it was all to do with my childhood,” wonders Brooks, “and the muddled, conflicted messages about authority, gender, and class I absorbed from the adults around me, my mother most of all.” The lessons are muddled indeed. “Sexism was bad and patriarchy was bad, I deduced, but so were femininity and passivity. Wars were unquestionably bad, at least when they took place in Southeast Asia, but toughness and aggression were clearly admired.” Barbara divorces her first husband, the noted psychiatrist John Ehrenreich, and marries a union organizer who is considerably less conflict-averse. Brooks enters a “tomboy stage,” and he recruits her to help him glue shop doors shut to spite management. She envies her younger brother, Ben (now a conflict journalist), for the attention Barbara gives him. By her teens, Brooks is deeply depressed, and is habitually skipping school. “No one asked me if something was wrong,” she recalls, and for all the family’s lively discussions of politics and philosophy, they “didn’t know how to talk to one another.”

These fraught relationships haunt Brooks’s experiences as a cop on the beat, as she is constantly drawn into the family dramas of the people who live in 7D, and in so doing turns inevitably to thinking of her own. On her first day on patrol, Brooks and another officer are dispatched to a call about a child being beaten in an apartment, only to engage in a frustrating conversation with a mother who will not let them in. “You can tell from right out there that my son is alive and well,” the woman says. “I know exactly what happens to black people when the police come barging into their houses!” Shortly thereafter, they respond to a call from another apartment, this time to be let in by a beleaguered woman, surrounded by piles of dog shit and an indeterminate number of toddlers. The woman tries to hand her eight-year-old boy off to them. “Listen, he’s going after his brother with a butcher knife and I need you to take him away.”

In yet another episode, which ranks among the book’s most disturbing, Brooks and a cop named Reid—a self-described “Second Amendment nut”—respond to a call involving a fight between a mother and her daughter. The girl is a 17-year-old whom Brooks gives the pseudonym Imani, and the proximate cause of the disturbance appears to be Imani’s asking her mother’s boyfriend for money. “I want her to go to jail,” the mother tells Brooks while Reid questions Imani in another room. When Imani tries to reach for her phone to show Reid that she had been the one to call 911 in the first place, Reid slides into Tactical Condition Red and grabs her. It gets worse. As Brooks tries to talk with Imani, Reid calls in to their sergeant and, together with him, decides “that Imani was the primary aggressor in what had now been redefined as a domestic violence assault situation, triggering a mandatory arrest.” Brooks narrates what follows:

It fell to me, as the only female officer present, to cuff Imani and pat her down. She didn’t complain or struggle. In her short life, I suppose, she’d already gotten used to things turning out badly. But it was one of my worst moments as a police officer. This girl was a victim, not a criminal. I thought of my own children, and imagined how my daughter would feel if both I and her grandmother seemed to be rejecting her. Would she want to lash out at me or hit me? If she did, I wouldn’t blame her. Adults are supposed to take care of children. Instead, I was attaching heavy metal handcuffs to Imani’s thin wrists. I felt a little sick.

Imani’s rejection by her mother is one of many episodes that make Brooks think of her own mother, “whose disapproval still rankled.” She compares her own childhood home to a prison, “each of us trapped in separate, solitary cells,” but recognizes her relative luck: “The prison bars I chafed against as a teenager were constructed from my own emotions, not from cold, hard metal.”

Whether you find such prose plangent or contrived may come down to taste. But set alongside one another, such passages cry out for evaluation in registers beyond the aesthetic. Brooks rightly demands we all dispense with euphemism and call putting people in “cages” what it is. But when it comes to examining her participation in that enterprise, she inevitably must turn to metaphor and projection. Washington’s mandatory domestic violence arrest laws left Brooks with hands that were figuratively tied, but only one person in that situation wound up in actual cuffs.

What is at stake here is more than Brooks’s word choices as a memoirist or her life choices as a person or her decisions as a cop. When Brooks first tells her mother about her plans to become a cop, Ehrenreich invokes Nietzsche’s line about how those who gaze long enough into the abyss will find the abyss gazing back into them. But what will Americans see when they gaze into this book? Is this a book that will give readers a new perspective on the violence of policing—or is this just the story of how cops, and by extension her readers, can make peace with it?

At several points, during quiet moments in the squad car, Brooks explains Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow to her partners. More than being unimpressed, they find it “offensive.” Their individual decisions to arrest people, they insist, have nothing to do with race. One, a black man, compares what cops do to the operations of ShotSpotter, a system of surveillance sensors that detects the sound of gunfire, triangulates locations, and dispatches police accordingly. “ShotSpotter can’t tell the color of the person firing the gun,” he says. “And what does she want us to do, ignore the 911 calls from black neighborhoods because if we go, we might have to arrest black people? The people calling 911 are black too. Don’t black people have a right to have us come when they call?”

It is in fact on the question of rights that Brooks is the most persuasive. “What if instead of telling officers they have a right to go home safe, police training focused on reminding officers that members of the public have a right to go home safe?” she asks. “What if we reminded officers that they are voluntarily taking a risky job, and that if someone dies because of a mistake, it’s better that it be a police officer who is trained and paid to take risks than a member of the public?” Simply posing these questions may well scandalize her other officers and may well be anathema in the era of Blue Lives Matter (a movement Brooks does not mention). But it is to Brooks’s credit that she asks them in first place.

It is also to Brooks’s credit that she provides the reader with context about how decades of segregation have concentrated poverty in various neighborhoods, and draws on the work of the legal scholar James Forman Jr., who has compellingly documented how class divisions within Black communities have often generated calls for more rather than less policing. By the same token, she lucidly describes how the erosion of social services and the criminalization of trivial disorder have put police in the position of all-purpose problem-solvers whom “we expect … to be warriors, disciplinarians, protectors, mediators, social workers, educators, medics, and mentors all at once,” and whom “we blame … for enforcing laws they didn’t make in a social context they have little power to alter.” Time and again, the reader is reminded how various structural factors attenuate certain disparities, what this or that policy means for the most vulnerable, and so on. All the requisite gestures, in other words, are there, and the all-too-familiar opposition between what “activists say” and what police and their backers insist is kept to a minimum. The balancing act is deft, even exquisite; beside Matthew Horace’s The Black and the Blue (written with Ron Harris), no other recent police memoir comes close.

But the slickness and equipoise of Tangled Up in Blue betray themselves. When Brooks addresses the broader discourse around policing, her efforts to consider “both sides” can feel flattening, patronizing, and even canned. “The existence of violent crime is not a right-wing myth dreamed up to justify the incarceration of minorities and the poor,” Brooks states. “Crime is real—and the misery, pain, and fear engendered by violent crime are visited most often on the very same demographic groups who are disproportionately likely to end up incarcerated.” Likewise, Brooks observes that while “critics of policing are justified in viewing both the stunningly high number of police killings and the racial inequities marring our criminal justice system as tragic and inexcusable,” it is also the case that “policing is not a malevolent conspiracy,” since “most police officers take seriously their role as public servants.”

Who, precisely, are these neatly worded, well-qualified reality checks actually meant for? Of course violent crime is “real.” Indeed, if there’s any one thing the must-read lists and book clubs that will spotlight Tangled Up in Blue have an appetite for, it’s True Crime. And what work is done by proclaiming that “policing is not a malevolent conspiracy” in an era when people can watch a biopic about the assassination of Fred Hampton, or Google newspaper coverage of the role of Rahm Emanuel in the Chicago Police Department’s cover-up of the killing of Laquan McDonald, or read Baynard Woods and Brandon Soderberg’s excellent I Got a Monster, which details a years-long robbery and drug-dealing enterprise within the Baltimore Police Department, a criminal enterprise for which some 15 officers have now been charged or convicted, many on literal conspiracy charges?

Brooks’s admonitions here seem geared toward self-consciously reasonable and presumably liberal-centrist readers who think “nuance” simply means well-balanced clauses and appeals to their own ability to tolerate complexity in lieu of actually thinking. They are fodder for the kind of people already inclined to congratulate themselves on their ability to listen to tough, real, and serious lessons from someone who is tough, real, and serious enough to put a teenager in handcuffs and then bravely bare their soul about how doing that made them feel. These are tics, ideological reassurances for people who would prefer not to think too long or too hard about how “policing” might not be a “conspiracy”—but only in the sense that it is precisely not any more or less a conspiracy than, say, high finance or municipal zoning.

Policing, in other words, is not a conspiracy insofar as “conspiracies” generally involve secrecy. The purpose and practice of policing play out transparently and in the open. ShotSpotter towers do not blanket wealthy white suburbs, and the reason is not that gun homicide is hyper-concentrated among the Black and poor, but that there are no equivalent systems for swiftly dispatching armed police in response to wage theft by retail managers, rape in frat houses, or cocaine use in yacht clubs. If the imperative driving individual police officers is to impose control and minimize risk, so too is this the basic principle that defines “policing” as a social institution more broadly. Capital and those closest to it must be secured in the sense of being kept safe—including from police officers themselves. Other people must be secured in the sense of being locked down.

“The real hell of life,” Jean Renoir once observed, “is that everyone has their reasons.” Whether knowing what these reasons are and being honest to one another about them makes any difference is probably a question for theologians, philosophers, and psychoanalysts. Brooks, to her credit, seems far more honest about her reasons than most, and her book is revealing. It would be reductive to say that Brooks simply uses the streets of Washington’s poorest neighborhood and the traumas of its denizens as stages and props for satisfying her own curiosity and proving something to herself, and working through personal family psychodramas. It would be simplistic also to see this book as just a giant plug for the new “Innovative Policing Program” at Georgetown that Brooks founded, or as a bid for some presumptive police reform czar appointment in a Biden (or Harris) administration. But it would also be naïve to see Tangled Up in Blue as not these things.

When Brooks gives her cop colleagues a crash course in The New Jim Crow, they respond in personal terms to being interrogated about their participation in mass incarceration. They are reassured by thinking of themselves as just normal individuals, operating on the ground floor of policing on a case-by-case basis, and making the same impersonal, disinterested, and fundamentally fair judgments as a fine-tuned machine. The Big Questions are above their pay grade. For her part, Brooks makes abundant and thoughtful gestures toward asking The Big and Difficult Questions, yet she does so while thoroughly personalizing everything. Presumably, many in her intended audience will be reassured to think that our system of policing could be administered at the highest levels by such an exceptional and formidable individual, operating with an eye on the big picture, and making decisions that fuse lived experience with empathy and impeccable credentials.

In the book’s final scene, Brooks, in full academic regalia, delivers a lecture at Georgetown on the occasion of an alumnus’s $10.5 million gift to the school, a donation that includes an endowed professorship for herself. Her police colleagues are there, as are her students, fellow professors, deans, and her instructors from the academy. So too is her family, including Barbara, who has finally come around and expressed motherly pride to her (“I shouldn’t have doubted you”). “Everyone was beaming up at me,” writes Brooks, “and I felt a sudden surge of joyous vertigo: all my worlds, finally converging.” Her life is fully integrated. Exciting partnership initiatives are in the offing, difficult conversations are being launched, and, finally, so many years after those tense exchanges in the Ehrenreich family home, people now have the ability to Talk to One Another. In the appendix, Brooks notes what happened to Imani. The prosecutors declined to press charges, but her relationship with her mother “remained contentious.” The police have been called to more disturbances at their home, and both her mother and her mother’s boyfriend have been arrested. In one episode, he set the house on fire.