Hao-Yuan Cheng is a night owl. So when an alert buzzed his phone in the early morning of December 31, 2019, he saw it almost immediately. Trained as an epidemiologist, Cheng works as a health official in Taiwan’s Centers for Disease Control, inside a special unit called the Epidemic Intelligence Center. Established after the 2003 SARS outbreak, the EIC oversees a 24/7 disease surveillance system designed to identify potential outbreaks. At all times, it is trawling the world’s chatter for what could trigger the next crisis.

At 2:24 a.m., a user on PTT, the popular Taiwanese internet forum, uploaded a batch of screenshots from Chinese social media. The posts warned of a mysterious pneumonia in Wuhan, a city of 11 million in central China. Cheng’s alarm peaked as he read the posts. “There were so many keywords,” he recalled: virus, contagion, infection, pneumonia, and, most unnerving of all, SARS. He compiled everything as quickly as he could, then sent the package up his chain of command.

The source of the messages was a Chinese ophthalmologist named Li Wenliang. At 5:43 p.m. the previous afternoon, Li had shared an anxious tip in a WeChat group with old medical school friends. The Wuhan Central Hospital, where he worked, he said, had just quarantined seven patients from a local seafood market. They had contracted the disease that would become known as SARS-CoV-2.

Li understood that disseminating this information could get him into trouble. He asked his former classmates not to share his post. But inevitably, his messages spread—first within the region, then overseas. Around the same time that Cheng, in Taipei, was forwarding the tip to his colleagues, the Wuhan health commission was ordering Li, in the middle of the night, to come in for questioning.

When Cheng arrived at work that morning, he was called into a task force meeting with the CDC’s deputy director general. False alarms were common, particularly those from China, and their job was to determine if the tip was credible enough to pursue. They decided that it was. By noon, they had sent a query to the World Health Organization, warning of an emerging viral pneumonia in China. It was New Year’s Eve.

The same day in Wuhan, Li was called into disciplinary meetings by his hospital’s “inspection” team, a division in charge of handling political matters. As China was pursuing leaks and issuing reprimands, Taiwan was already implementing safeguards. Starting on December 31, all inbound passengers from Wuhan received mandatory health screenings. Two days later, the Taiwanese CDC established a rapid response team to monitor the outbreak.

On January 3, Li was summoned to a Wuhan police station, where he signed and fingerprinted a letter confessing to “untrue speech.” A state broadcast reported on seven other “rumormongers” in the area.

Soon after, Taiwan dispatched two veteran scientists on a fact-finding trip to Wuhan. A press conference was scheduled for January 16, on the morning after they returned. The two experts shared details from their visit and accepted questions from journalists. “Transparency was our key to building confidence,” Cheng told me recently. “We took actions to let people know we’re not hiding anything.”

Wuhan locked down on January 23. Trains and flights ground to a halt, severing the city from the world. On February 6, Li Wenliang died of complications resulting from the coronavirus. He was 34 years old. As the news circulated online, Chinese social media posts with the hashtag #WeWantFreedomofSpeech were viewed millions of times. All were removed by morning. A few days later, the Chinese novelist Fang Fang, a Wuhan native, published a blog post addressed to the country’s “internet censors.”

“We have witnessed so much tragedy,” she wrote. “If we cannot even be permitted to say a few words in exasperation, express grief, or reflect on what has happened, we will surely all go mad.”

From the beginning, China and Taiwan, separated by a mere 81 miles of water, represented two different approaches to quelling the pandemic. Both models have halted contagion, stemmed infections, and allowed much of normal life to resume—notable feats next to the sluggish, chaotic response of many advanced Western democracies. China’s blunt tactics, in particular, have drawn cautious praise around the world—including from the United States. The New York Times wrote that the country’s strong-arm approach “has positioned China well, economically and diplomatically, to push back against the United States and others worried about its seemingly inexorable rise.” In a segment deriding Americans as “silly people,” talk show host Bill Maher said, “China sees a problem and they fix it.”

As the Covid crisis heats up a global contest of ideologies, the Chinese Communist Party has claimed vindication—showcasing its authoritarian competence against the omnishambles of Western-style democracy. Yet the story in Taiwan shows this binary to be a false one. Sixteen months after confirming its first case, the island nation of 23 million people has recorded roughly 4,300 total cases and only 23 deaths, more than half of which were tallied in the past week. For 253 consecutive days last year, between April and December, there was not a single reported case of domestic transmission. Until earlier this month, there had been no lockdowns, no community spread. For a year and more, the country was living in a post-Covid future.*

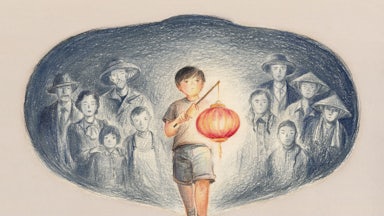

Taiwan is proud of its model. As it rallies now to rein back a fresh local outbreak, the Taiwanese government and people are drawing upon their many successes—in previously containing the virus, in upholding democratic values, and in coming together in common cause—to light a path that may help America and others not only better manage the next pandemic, but become better democracies, too.

In the summer of 2003, Jason Wang visited Taipei in the wake of the SARS outbreak. At its height a few months earlier, the city’s government had responded by abruptly sealing a local hospital. Panic spiked. Doctors and nurses hung white bedsheets from the windows, begging to be let out. In the end, that one hospital accounted for more than a third of Taiwan’s 346 cases. Across the country, there were 84 deaths—the third-highest count in the world, after Hong Kong and mainland China. Medical and government leaders committed to do better.

A shadow hung over the city. Its people were shaken. Wang, a Harvard Medical School graduate who was born in Taiwan, has a photograph from that time showing his two-year-old daughter in a face mask.

Today, Wang is the director of the Center for Policy, Outcomes and Prevention at Stanford University. He has followed Taiwan’s epidemic response measures closely. Beginning in 2003, changes to the Communicable Disease Control Act have strengthened the government’s regulatory powers during health crises. In 2005, the National Health Command Center was established to coordinate the state’s various ministries and agencies.

Since the SARS outbreak, legislators have passed clear rules on a range of epidemic-related issues, including preserving safety equipment stockpiles, recruiting and deploying health personnel, and implementing mandatory quarantines. All this despite a fierce rivalry between the country’s two main political parties, which have long been divided on Taiwan’s relationship with mainland China after their split in the 1949 Communist Revolution. “Taiwan’s legislature is not exactly an easy place,” Wang told me. Yet public health proposals have consistently received bipartisan support. The most recent amendments, addressing epidemic-related misinformation, were approved in June 2019.

Wang was back in Taipei at the start of 2020, as reports of the novel coronavirus were first surfacing. He kept a daily journal where he cross-checked Chinese and American news accounts with every new policy announcement by Taiwan’s health ministry. Heightened border procedures soon led to the early detection of a 55-year-old woman experiencing fever, cough, and shortness of breath. After flying from Wuhan on January 20, she was transported from an airport health screening directly to the hospital, bypassing community contact. The next day, tests confirmed she was positive for Covid-19.

Passengers and crew on the infected patient’s flight were required to conduct 14 days of self-monitoring. Infectious disease staff called daily to check in. The United States confirmed its first case on the same day—a 35-year-old man admitted to a Washington state hospital after he had been out in public for several days. By then, hundreds of cases may have been spreading through the country. The “virus might already be here,” said a U.S. Health and Human Services official on January 23. “We just don’t have the tests to know.”

As David Wallace-Wells recently showed in New York magazine, urgent and decisive action was critical to successful campaigns in Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and elsewhere. In Taiwan, the government got an early jump on Covid because of its experience with SARS. Devastated 17 years earlier, it was ready.

Another important factor was the presence of an efficient and inclusive health care system. Established in 1995, Taiwan’s National Health Insurance is a centrally managed, single-payer system, covering around 99 percent of Taiwanese citizens. “We have the most egalitarian health system in the industrialized world,” touted Ching-chuan Yeh, a former health minister. On January 27, NHI integrated its centralized patient database with the immigration and customs database, enabling health providers to quickly identify and manage high-risk cases. Authorities were also able to seek out patients with severe respiratory symptoms and retest them for Covid-19. “That was really a new application of big data,” Wang said.

What impressed him more was the government’s ability to marshal the private sector. Expecting demand for face masks to surge, Taiwan banned their export the day after Wuhan was sealed. As the outbreak spread globally, other countries began reporting mask shortages. Authorized by a special Covid-19 law, the Taiwanese government quickly recruited 73 new factories and created more than 90 supply lines to produce and deliver surgical-grade masks. A temporary rationing system ensured that masks were available to everyone at a low price—initially five New Taiwan dollars each, or roughly 17 American cents. By April, domestic mask production had increased eightfold—from fewer than two million a month to just under 16 million.

Taiwan’s mass production and distribution of masks kicked into gear as top U.S. health officials were still debating the merits of using them. Taiwan benefited from past practice: Mask-wearing has been common in East Asian countries since before the pandemic. But the mask drive also exemplified the government’s resolute decision-making before a global medical consensus had coalesced.

Wang watched with regret as the situation back home grew worse. “In the U.S., we have a very complicated federal system,” he said. “Plus, the states have a lot of power for health matters.” The patchwork of approaches, particularly in a polarized political environment, led to chaos. People crossing state borders encountered different rules for mask-wearing, social distancing, and quarantining. Governors bid against governors—and against the federal government—for scarce supplies. There was no real federal response to speak of, and the virus spread.

In Taiwan, Wang saw how a strong, functional state could act to relieve a concerned population. “The responsibilities were well-delineated,” he said. “There were good laws already in place from the last 17 years for what the central government ought to do.” He realized the policies he had been tracking offered a template for how an effective public health system should operate. A colleague told him, “Jason, why don’t you write this up?”

In early March 2020, Wang published his findings in The Journal of the American Medical Association. His article documented all the measures taken by Taiwan’s government in the initial five weeks after recording its first case. Wang counted 124 actions in total, from penalizing PPE profiteers to issuing monthly subsidies for furloughed workers. “Taiwan is an example of how a society can respond quickly to a crisis and protect the interests of its citizens,” he and his co-authors wrote.

Articles in scientific journals don’t typically go viral. Since its publication, Wang’s JAMA article has been viewed over 1.1 million times. “I’ve gotten inquiries from almost all the continents,” Wang said. “Countries are trying to create their own checklists.”

Yet decisive state actions only captured half the picture. What allowed the Taiwanese government to act decisively in the first place was a high degree of social trust markedly absent in the United States. This trust did not spring naturally from Taiwanese society, nor from “Confucian” elements within East Asian culture. Audrey Tang, the country’s digital minister, credits the country’s strong cohesion to a series of calibrated “micro-steps that each earns trustworthiness.” Taiwan’s sense of unity, in other words, is not innate. It was attained—both historically and in real time.

Taiwan’s CDC is in a white, 10-story building in western Taipei. On January 20 last year, the Taiwanese government activated the Central Epidemic Command Center to spearhead counter-pandemic efforts. Perched on the seventh floor, the command center is the brain of the government’s Covid-19 response. Public health officials dart between offices, compiling data, arranging logistics, coordinating with local governments, and hosting video conferences.

On a recent afternoon, I took the stairs to the basement and joined Taiwanese media for the CECC’s routine press conference. Five senior health officials sat on a low stage separated by Plexiglas dividers; in the middle was Chen Shih-chung, Taiwan’s health minister and the CECC’s commander. For an anxious public, Minister Chen’s regularly scheduled press conferences, which began on January 3 last year, have served as a lighthouse through the rapidly evolving pandemic. According to Hao-Yuan Cheng, the Epidemic Intelligence Center official, some experts had initially considered limiting what the government shared, so as not to overwhelm the public with too many technical or bureaucratic details. What they found instead was “if you decide to take a very open attitude for this kind of communication, people will voluntarily try to understand,” Cheng told me.

The daily broadcasts became a national ritual—a scientific and political photo negative of President Trump’s grandstanding press conferences that overtook U.S. airwaves last spring and summer. CECC officers disclosed everything from the latest medical discoveries, to their rationale behind new policies, to the particulars of new cases (keeping personal identities anonymous). “At two o’clock in the afternoon, everybody is watching the same channel,” said Wang, the Stanford health policy director. “People were figuring out their own risks.” Viewers learned, for example, that case No. 380 was an asymptomatic male in his twenties, who lived in the same dormitory as case No. 322. They learned about transmission risks and contagion patterns, and the importance of social distancing. The program “pretty much trained everybody to become epidemiologists,” Wang said.

The press conferences also stood out for how they involved regular citizens. In February, a Taiwanese professor found that rice cookers could be used to sterilize surgical masks for reuse. After the government tested his claims, the CECC invited the professor to a live demonstration. Aides helped Minister Chen set up a rice cooker on stage, then properly fit his mask inside. When it was done, Chen gave his treated mask a sniff, smiled, then swiftly hooked it back over his face.

Not long after, a young boy called the agency’s hotline with an urgent concern. His parents had brought home pink face masks, and he was worried the other kids at school would make fun of him. The following day, Chen and his aides walked on stage all wearing pink-colored face masks. The gesture rallied the country. Celebrities, professional athletes, and even the president followed his lead, embracing pink face masks in a wave of solidarity.

In June, after two months without recording any locally transmitted cases, the CECC pared back its press conferences to once a week. By then, a self-reinforcing cycle had taken hold. Trust fostered success, which then bred more trust. Even as other countries succumbed to second and third waves, Taiwan’s case count has remained remarkably low.

The day after the press conference, I spoke with Tsung-ling Lee, a legal scholar at Taipei Medical University. Special regulations had consolidated executive power to fight the virus, but she noted instances in which the state reached for a different tool: restraint. In February last year, organizers were preparing for the Dajia Matsu Pilgrimage, Taiwan’s largest annual religious event, with tens of thousands in attendance. Health officials had called for the event to be postponed, yet temple leaders insisted on proceeding. In Taipei, Chen demurred. Speaking at a news conference, he explained the virus was “very disadvantageous” for such large crowds and bade followers not to upset Matsu, the Chinese sea goddess. But he stopped short of issuing a mandate. “Legally they could have used the law to prohibit the event, but they didn’t choose that route,” Lee told me.

Within a day, there was an outpouring from medical experts and everyday citizens reproaching the temple’s decision. In one online poll, 94 percent of respondents supported canceling or rescheduling the procession. In the end, the pilgrimage organizers bowed to the public response and announced they would postpone the event until the pandemic had stabilized. Lee told me that, under its expanded powers, the government could prohibit any event with more than 500 people. “But they tried to include the people in the decision-making,” she said. “The government reached out to the religious leaders and tried to include them in the conversation.”

In Taiwan, authority and prudence expanded in tandem, with a vigilant eye against the specter of state overreach. For quarantines, the government’s mobile tracking technique employs location data relative to nearby cell towers, creating a “digital fence” considered less intrusive than GPS. After 28 days, the data is deleted. The government’s special powers, granted early in the pandemic, are set to expire this June.

The level of trust between Taiwan’s government and its citizenry is all the more extraordinary when you consider that Taiwan is still a very young democracy. “I was born within the martial law era and remember that era,” Tang, the digital minister, told me. That period of subjugation formally ended in 1996, when Taiwan held its first free presidential election—a society that remade itself, mid-flight, following decades of clipped wings under the Kuomintang’s one-party rule.

The promise of democratic governance has been replenished by a vigilant civil society. Born after martial law, a new generation of Taiwanese came of age with privileges and freedoms foreign to their parents. Many of them never knew the censures of a one-party state, yet they learned not to take that for granted. In the fall of 2008, En-En Hsu was a sophomore in high school when hundreds of students convened outside a government building in Taipei. They were protesting a controversial visit by a high-ranking Chinese official, who had come to embody the Kuomintang-led government’s deepening ties with the mainland. The following day, students in Kaohsiung, the southern port city where Hsu lived, organized a similar sit-in. Within a week, demonstrations had spread to a half-dozen cities.

Participants called themselves the Wild Strawberry Movement—both a nod to their forebears in the Wild Lily Movement, the 1990 youth-led demonstrations that helped usher in Taiwan’s democracy, and an attempt to subvert a common pejorative. Coined by older Taiwanese, the “strawberry generation” had become a popular nickname for the cohort born after 1980, whose upbringing through conditions of comparative ease was said to have eroded their tolerance for hardship. They were said to bruise easily, like strawberries.

After moving to Taipei for college in 2011, Hsu quickly became active in social justice groups. Because her university was far from the city center, she rarely left campus except to attend protests. By the end of her first year, she knew little of Taipei’s night markets or shopping malls, but was intimate with the layout around government offices. In the spring of 2014, she began participating in rallies to oppose a divisive trade bill with China.

Negotiated in private between Kuomintang and Chinese officials, the Cross-Strait Agreement on Trade in Services was meant to further integrate the Chinese and Taiwanese economies. Opponents of the bill feared that such interdependence would jeopardize Taiwan’s autonomy, but many took greater offense at the government’s opaque dealmaking. A Kuomintang legislator had concluded a promised item-by-item review after less than a minute. In what became known as “the 30-second incident,” he introduced the bill for committee review, then in the same breath declared the bill was ready and adjourned.

On the evening of March 18, Hsu joined a few hundred others gathered in front of the Legislative Yuan, or parliament. It was like all the other demonstrations, until it wasn’t. One minute the protesters were outside giving speeches, then the next they were rushing up the steps, pushing against the glass doors. Suddenly they were through, fanning out inside the chamber. The occupation had begun.

Chants of “defend democracy” filled the legislature. Under the portrait of Sun Yat-sen, the first leader of the Kuomintang, posters and banners proclaimed HEAR THE VOICE OF FREEDOM, LIGHT THE LANTERN OF DEMOCRACY, and THE YOUTH ARE RECLAIMING CONGRESS. NGOs arrived to give aid; scholars, activists, and lawyers provided counsel; small groups linked arms, breaking intermittently into song. Sunflowers delivered by a local florist became a symbol for the occupiers, seen to be shedding light into the government’s “black box.”

The Sunflower Occupation drew from all walks of life. Sheau-Thng Peng was a journalism student, assigned to cover the Legislative Yuan for class, when she was swept inside by the tide of demonstrators. After broadcasting all night from within the legislature, she stepped out in the early morning to get some air. What she saw startled her. “Every street was full,” she told me. “There were all kinds of people.” Peng and her classmates subsequently interviewed as many of them as they could. “There were elderly grandmas who said they wanted to support the youth,” she recalled. “There were parents who brought their young children. It was much more than just students and young people.”

Over 24 successive days, the occupation’s ranks grew. Surveys later found that the majority of Taiwanese supported greater scrutiny of the trade bill. The movement had drawn more than 350,000 participants, filling the streets with speeches and song. Surrounding the Legislative Yuan, an expanding tent city featured subdivisions for performance areas, art exhibitions, student encampments, and vendor markets. A “Democracy Café” served free coffee; a noodle stand supplied hot bowls of “Liberty noodles.” Occupiers participated in yoga workshops and therapy sessions and massage circles. When tensions turned physical, doctors arrived in white hospital gowns. When arrests broke out, lawyers leaped to the front in dark robes. “It was incredible,” Peng told me. “You had no idea where all the help was coming from. After that, I truly believed—this is Taiwan’s civil society.”

Sunflower leaders adopted a big-tent approach: At its peak, the movement housed as many as 54 civic groups with varying intents and ideologies. Such diversity led to clashing viewpoints, but the sheer volume of coordination also led to results. In early April, the legislative speaker promised to shelve the Cross-Strait Agreement until further review. Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao, a veteran sociologist at the Academia Sinica in Taipei, told me that Taiwan must be understood as a “movement society.” Recurring cycles of protest and resolution link to form a “progressive pattern of evolution,” he said.

During the 2016 presidential election, shifting demographics and a more assertive post-Sunflower electorate helped lift Tsai Ing-wen, leader of the opposition Democratic Progressive Party, into office with nearly twice the votes of her Kuomintang opponent. Last May, buoyed by her administration’s striking success against Covid-19, Tsai took the oath for her second term, with more than 70 percent approval—the highest level on record.

In the wake of the Sunflower Occupation, many in Taiwan’s civil society came to see government as an effective space to cultivate change. The DPP, which has historically advocated greater sovereignty from China, was eager to embrace them. Young Sunflower participants campaigned for President Tsai’s 2016 campaign, worked as aides to DPP lawmakers, and later took positions in various government agencies. Others launched their own political parties and announced their candidacies in local races.

Ming-sho Ho, a sociologist at National Taiwan University, told me that such moves reflect the “permeability” of Taiwan’s democracy, where a porous border exists between the government and its subjects. Among the activists who passed through was the “civic hacker” Audrey Tang. Before her 2016 appointment as Taiwan’s digital minister, Tang had worked for years as a pillar of g0v (pronounced gov-zero), a collective of Taiwanese programmers dedicated to creating public tools from open government data. During the Sunflower Occupation, g0v was instrumental in supporting the legislature with internet and live-streaming. Tang had documented the first wave to secure the assembly floor.

It was not her first experience in politics. As a teenager in 1996, Tang volunteered in Taiwan’s first free presidential election, helping build campaign websites. She watched as the blossoming of her country’s democratic future commingled with the mass adoption of online tools able to enhance it. “That was the beginning of Taiwan’s democracy,” she said. “From the very beginning, it was powered by the web.”

Key to Taiwan’s effective Covid-19 response, Tang told me, was an active and engaged social sector from the beginning. Many of the 124 actions identified by Wang’s JAMA article married digital technologies with efforts from outside government. Nonprofit initiatives like the Taiwan FactCheck Center, a collaboration between journalists and communication scholars, launched a campaign to counter disinformation. Even as cases in Hong Kong and South Korea spiked into the thousands, socially coordinated behaviors such as crowdsourced fact-gathering and good-faith reporting helped Taiwan keep transmissions low.

When I met Tang recently in Taipei’s Executive Yuan, her office was neat and spare, with a virtual reality headset resting over a sheaf of documents on her desk. Critical to her department’s success has been a lively civic hacking community, which contributed a real-time mask availability map that became one of the country’s biggest hits. The map was launched by a 35-year-old programmer who had noticed his friends and family stressing over mask shortages. After thousands of users flooded the app, Tang seized on the initiative and amplified it. She secured government resources, opened up national health data, and mobilized her g0v colleagues, at one point dropping live requests directly into the group’s 8,000-member Slack channel. Developers from around the country volunteered their own time to clean up bugs and add new features, which were all released for free.

During the map’s first week in operation, almost one million people in Taiwan used it. Tang believed it might be the first instance in history that “civic tech became, essentially, public infrastructure.” She paused to consider: More people were probably using it than even the country’s busiest highways. She pursued the logic: If the map was indeed public infrastructure, then the civic hackers who built it were effectively civil engineers. This was her job—blurring the line between the state and its people. “I’m more like a spokesbot—a spokesperson of this collective intelligence,” she said. “A lot of the real work is done in the social sector. I’m a bridge that amplifies their work, but it is their work.”

This past January, China encountered its largest cluster of domestic Covid-19 transmissions in months. In the first two weeks of the year, more than 600 cases were reported in Hebei, the northern province surrounding Beijing. The state dashed into action.

Over 22 million residents in three Hebei cities, including the provincial capital, Shijiazhuang, were sealed off. Flights and trains were canceled; highways were closed; stay-at-home mandates were issued and enforced. The State Council set new rules for testing, giving big cities two days to process up to five million people. In Gaocheng, Shijiazhuang’s hardest-hit district, more than 20,000 people were evacuated into a centralized quarantine site. “I don’t understand; I feel like a refugee,” recorded one villager in an online video, after packing two fertilizer sacks with clothes for herself and her children. “I guess we obey the nation’s arrangements. If they want us to move, we move.”

But the nation wanted most Chinese to stay put. A Shijiazhuang high school student told the Los Angeles Times. “Even if your family member dies you can’t move.”

Seizing on dysfunction in America and the West, China has spun its mobilization against the virus into a narrative of fortitude and triumph—one that obscures key failings to control the outbreak’s initial spread. The government in Beijing banned criticism of the lockdown on its one-year anniversary, has disappeared and convicted citizen journalists, and silenced grieving relatives. Crucial missteps—such as the early undercounting of infections, a bureaucracy incentivizing doctors and local officials to keep silent, and the late admission of human-to-human contagion—have been expunged, wasting valuable opportunities for reassessment and improvement.

Implicit in the party’s official telling is the premise that tolerant, democratic governance will result in American-style chaos. In Washington, partisans traded barbs over face masks, social distancing, lockdowns, quarantines, school reopenings, state subsidies, supply rations, medical treatments, and relief checks—a parade of embarrassments that showed, again and again, their own political interest was more important than science or facts. In Beijing, party leaders decided their own political interest was in not letting people die—at whatever cost was necessary. Five weeks after the authorities sealed Wuhan, total cases in China began to plateau at around 80,000. At its peak this past winter, the United States recorded more than 200,000 new cases and 3,100 deaths in a single day.

In a recent Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law article, the political scientists Matthew Kavanagh and Renu Singh suggested a country’s “state capacity” to handle crises must be considered alongside its “political capacity.” They cited the 2019 Global Health Security Index, in which the United States ranked first out of 195 countries in nearly every category of preparedness—from threat detection to prevention and response. In Kavanagh’s view, the 2020 pandemic has exposed America’s advantages—including “strong infrastructure” and “stability”—to be woefully insufficient. Given that “the state, in all its capacity, must be mobilized through political processes,” they argue that a true accounting of public health preparedness must also consider such factors as federalism, polarization, party ideology, and even the competence of individual leaders.

The day after his inauguration in January, President Joe Biden released his national strategy for defeating Covid-19. In the first of seven goals, he pledged to “restore trust with the American people.” To that end, his administration has vowed to track and release more data, enhance communication with the public, and “put science first.” Yet the plan stops short of confronting necessary overhauls, not least in an underfunded public health system that leaves nearly half of American adults inadequately covered. Despite efforts to better coordinate among agencies, there has been no reassessment of government’s fundamental role in protecting the country against public health and other emergencies. In March, lawmakers began talks on a bipartisan proposal to combat the next pandemic. But without a broader alignment between the two parties, there is little guarantee that even the best-laid plans on paper will not flounder again in execution.

Audrey Tang sees a world in which the pandemic is likely to accelerate current trajectories. Authoritarian regimes will amplify fear and repression, while liberal societies will either strengthen existing links between citizens and state or allow them to further deteriorate. The true legacy of Taiwan’s Sunflower Occupation, she told me, was that it helped the country relearn “how to live together in a real democracy.” Expectations of accountability were rewired; norms were reset. People reclaimed their responsibility to keep the government—and themselves—honest. Despite America’s stumbles, she still believes it has a leading role to play. “At the end of the day, a democratic system is self-healing, is resilient,” she said.

Resilience is what fosters change—for individuals and countries alike. It is what allows a people to defeat a virus, and to engender a healthier society. In her past activism, Tang helped translate the work of Manuel Castells, a Spanish scholar of global social movements. In Castells’s recent book, Rupture: The Crisis of Liberal Democracy, he looks upon the future. “The old order is dying and the new one is yet to be born,” he writes. “What is this new order that must … replace what is dying?”

He adds, “What possible forms could this new politics take?”

* This article has been updated to include the latest Covid figures.