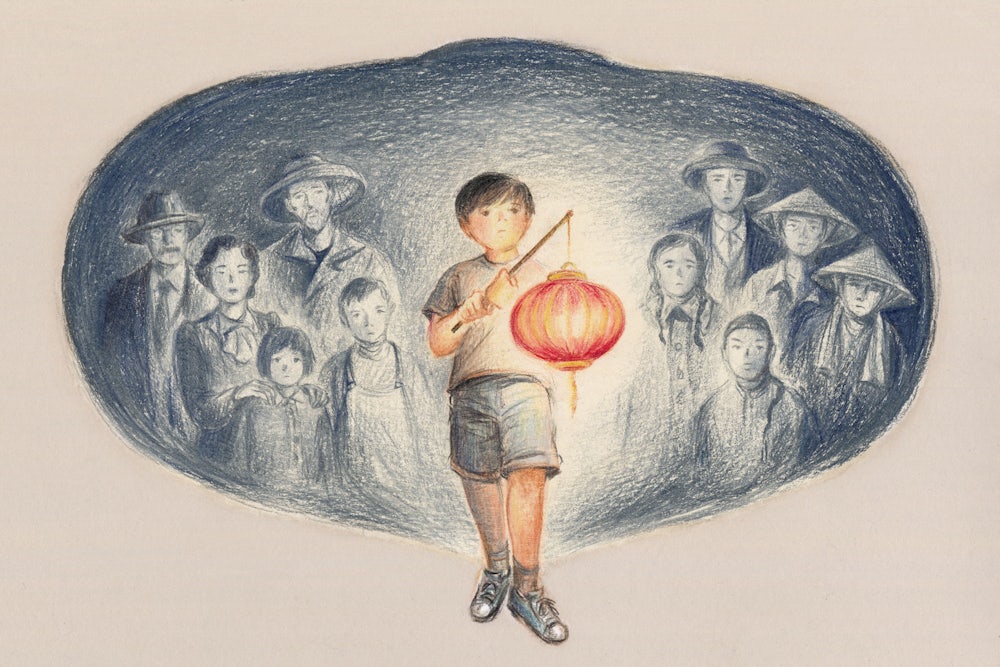

On Chinese New Year a few months ago, my parents showed me President Joe Biden’s Lunar New Year greeting. Against a backdrop of traditional red-and-gold silk cushions, the president and first lady Jill Biden wished blessings upon the Asian American and Pacific Islander communities: “In this season of renewal, may we all find strength and joy in one another.” Even as a heart-hardened politico, I felt a sudden sense of relief. The days of “the China virus” rhetoric from the White House were over.

A month later, a shooting at a massage parlor in Atlanta killed six Asian women. In response, #StopAsianHate marches spread across the nation, including in my Chinatown neighborhood. Perhaps after four years of Trump, marches couched in the reductive language of individual “bias” are enough for some. But long before Trump took office, xenophobia, anti-Asian racism, and Yellow Peril–style propaganda served as useful tools to advance American domestic and foreign policy goals. They may yet again.

In recent decades, the defense industry has perfected this rhetoric to make the case for war on China. Republicans and Democrats—including both President Biden and even our most progressive members of Congress—amplify the warmongering and push for increased defense spending. There is no violence like the mass rape and murder of war, yet in this moment of outcry against anti-Asian violence, lawmakers in D.C. are bringing us to the brink of global conflict. Asian and Pacific Islander peoples around the world—who are, like my grandparents living in China, often loved ones of people here—will suffer that violence. And as in all wars, the enemy abroad becomes the enemy at home, making Asian Americans at home once again the target of state and community brutality.

In the United States, we commonly understand “Yellow Peril” as a xenophobic response to influxes of Chinese laborers. Yellow Peril produced national shames such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which remains the first and only ban on all immigrants from an ethnic group. But the propaganda also supported foreign policy. In the late nineteenth century, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany supposedly dreamed of Buddha seated on a dragon, threatening to invade Europe. He used Yellow Peril (die Gelbe Gefahr) to build alliances with other imperialist nations and justify invading China first lest the East conquer the West. In the Opium Wars of the 1840s, the U.S. and other Western nations killed 30,000 Chinese people so that they could forcibly sell opium to civilians, while notable Americans and elite institutions such as Harvard, Yale, and Princeton built their wealth on opium colonialism. This is the foundational moment of U.S.-China relations.

Today, Yellow Peril propaganda is bipartisan and mainstream. Indo-Pacific commander Admiral Phil Davidson’s warning of China’s “pernicious” and “malign” influence, an Atlantic Council report that lengthily describes how “China presents a serious problem for the whole of the democratic world,” Senator Jim Inhofe’s belief that “we’re in the most dangerous time of our lifetime”—these are only the tamest examples of such rhetoric on China. Dan Grazier, the Jack Shanahan Military Fellow at the Center for Defense Information at the Project on Government Oversight, notes that at the Senate confirmation hearings for Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, China was mentioned at least 70 times.

Critical to this contemporary promotion of Yellow Peril is the image of China as the military aggressor. But right now, the U.S. has 800 overseas military bases, half of them encircling China. China has one (in Djibouti). The U.S. spends more on defense than the next 10 nations combined, including China. The U.S. has extensively planned for a naval blockade of China, cutting off its oil supply. The U.S. has 20 times the nuclear warheads of China and yet is still spending an additional $100 billion to build up a new nuclear arms arsenal. The U.S. Indo-Pacific Command has stationed 130,000 troops in the region, conducting nearly daily military exercises with drones, missile drills, helicopters, island hopping and more, according to Madison Tang, campaign coordinator at CODEPINK. “These military exercises create accidents. These exercises can be provocations in and of themselves. There’s a lot of military brinkmanship happening where American forward posturing [is being] framed as defensive,” says Tang.

The brinkmanship began in 2011 with former President Barack Obama’s “pivot to Asia,” which transferred 60 percent of American air-naval forces to the Asia-Pacific. Many of these forces are based on the Pacific Islands, including Guam, Okinawa, Palau, and the Chagos Islands, where the U.S. military has deported Indigenous peoples, excavated sacred lands, committed mass sexual violence against women and children, and poisoned drinking water with chemical and biological weapons. We rarely question such contemporary colonialism, but Pacific Islander Indigenous sovereignty is only table stakes in the American “pivot to Asia.”

Indeed, the same people and organizations calling China a grave threat nakedly reveal the real reason for American brinkmanship. The Council on Foreign Relations reports in 2015 that “preserving U.S. primacy in the global system ought to remain the central objective ... in the twenty-first century.” President Biden himself wrote in 2020, “The Biden foreign policy agenda will place the U.S. back at the head of the table.… The world does not organize itself.”

China is not a threat because it’s attacking U.S. soil. China is a threat because it threatens American global hegemony. Here the underlying logic of Yellow Peril becomes clear. Proliferating the false idea that China will take over the West rationalizes starting conflict in the Asia-Pacific; this nearly perfectly parallels the geopolitical theater of a century ago. The Yellow Peril, the faceless horde, the ever-growing yellow population, an existential threat to the West, to liberal human rights, to the market economy, to the “rules-based” order, to American primacy.

In 2021, an elderly woman was knocked to the ground and kicked in the stomach in midtown Manhattan. Before walking away, the alleged attacker said, “Fuck you, you don’t belong here.”

In 1989, two white men ambushed and pistol-whipped Chinese American Jim Loo, killing him. They blamed Loo for American soldier deaths in the Vietnam War. “Our brothers went over to Vietnam, and they never came back.”

In 1982, two white autoworkers beat Vincent Chin to death with a baseball bat. They blamed Chin, a Chinese American, for the rising competitiveness of the Japanese auto industry and decimation of the Detroit Big Three. “It’s because of you little motherfuckers that we’re out of work.”

In 1954, courts convicted Eugene Moy, the editor of the leftist China Daily News, for running advertisements for Chinese banks. He died shortly after his release from prison. A white mob had just rampaged in a Chinatown restaurant in San Francisco to “avenge American deaths” in the Korean War.

Who we define as our international enemy, or perhaps just competitor, also becomes our enemy at home. These incidents are not accidents—they are collateral damage—because Yellow Peril and its relatives xenophobia, sinophobia, anti-Asian racism, and McCarthyism have always been tremendously useful in building consensus in the American public.

Grazier describes a military-industrial-congressional complex first warned of by President Eisenhower in 1961. Defense industry money drives increased military budgets in three ways: defense contracts, operating like pork barrel, that impact the districts and constituents of members of congress; political contributions to congressional campaigns and at least $100 million in annual defense lobbying; and the funding of a national security elite, including $1 billion for think tanks such as the Center for New American Security, the Atlantic Council, and the Council on Foreign Relations, which launder industry interests through mainstream media.

“There’s a lot of talk about flat budget levels. That’s distressing for Pentagon people who want to fund their pet weapons projects,” says Grazier, explaining that defense spending has typically increased during conflicts but can also grow during peace times if officials “talk up an existential military threat” to justify the budget. That new foe is China.

In 2020, a bipartisan group of senators and Admiral Davidson established a new fund for militarism in the Asia-Pacific, the Pacific Deterrence Initiative, or PDI. In March of this year, Davidson asked for $27 billion for PDI to pay for new airfields, long-range missiles, space-based surveillance radars, joint exercises, and more. President Biden’s initial budget, released last month, signals “most, if not all” of these PDI requests will be funded; identifies China as the top “threat”; increases defense spending by 1.6 percent; and allocates half of our nation’s discretionary budget toward defense.

Richard Falk, professor emeritus of international law at Princeton University, notes, “Biden is very much a creature of Cold War bipartisanship. His comfort zone was established by this western alliance against the Soviet Union and communism. Therefore I was worried during the campaign that [Biden] was going to try to reconstitute bipartisanship in foreign policy while pursuing a more partisan agenda domestically. That’s precisely what has happened.”

This summer, the Senate will likely pass a broad, bipartisan package to counter China, including the Strategic Competition Act, which contains a number of hardline stances, some inserted by Senator Marco Rubio. The act expands unilateral sanctions on China, requires referring to Taiwan as a government, and strikes references to “One China” policy. According to Tang, the act also appropriates $100 million annually for 2022 through 2026 for the U.S. Agency for Global Media—including government propaganda programs, such as Voice of America and CIA-backed Radio Free Asia—to spread information on “the negative impact of activities related to [China’s] Belt and Road Initiative.”

Tang speculates the Belt and Road Initiative is targeted because it isolates U.S. trade power and therefore reduces U.S. sanction power. The appropriation is part of a larger $1.5 billion Countering Chinese Influence Fund to combat the “malign influence of the Chinese Communist Party globally.” The act also requires that the Committee of Foreign Investment review any higher institution donation above $1 million for fear of espionage. Senator Mitt Romney recently said he’s “very, very reluctant to bring in students from China ... here to steal technology.”

The Strategic Competition Act—and the rhetoric around it—echoes sinophobia during Cold War McCarthyism, when the FBI banned Chinese Americans from transferring money to their relatives in China who depended on them for survival, tapped phone lines, interrogated an officer of the leftist Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance until he committed suicide, demanded 40 major Chinese American associations produce full records and photographs of their membership within 24 hours, and imprisoned and deported Chinese American intellectuals. When the U.S. is in conflict with another nation, that nation’s diaspora becomes the target of state suspicion and violence here.

The bipartisan Strategic Competition Act is part of Biden’s larger infrastructure proposal, which he pitched in his first address to Congress, arguing we’ll lose to China without it. Progressives celebrated his speech, taking the seemingly not-so-bad (anti-China rhetoric) with the good (massive investments in jobs and infrastructure).

There is “in the Democratic party a desire to [use] a new cold war with China as a tool to organize politics in the U.S. Traditionally, much liberalism after World War Two is Cold War liberalism. Keynesian stimulus is tied to military spending, and you see the Department of Defense as a tool for economic development,” says Chase Madar, legal scholar, adjunct professor at NYU, and author of The Passion of Chelsea Manning. “Good jobs shouldn’t have to depend on a foreign threat, but according to the political logic of many in Washington, that’s what you need to do to make it palatable and salable to people.”

This trade is not only short-sighted, it is immoral. Protracted war, including nuclear, is a “very real possibility,” especially because the U.S. rejects committing to a no-first-use policy for nuclear weapons. Military and military-adjacent spending is some of the least efficient stimulus the government can engage in when compared to investments in education and health care. As warmongering escalates, the powerful military-industrial-congressional complex will likely swallow a larger share of the federal discretionary budget than Democratic consultants had originally planned. Moreover, anti-China rhetoric is easily transformed into anti-socialist rhetoric, the growth of which would make other progressive priorities, such as universal health care, politically toxic.

Washington elites have largely been successful in moving the public toward confrontation with China. The percentage of Americans who view China as our greatest enemy doubled from 22 percent to 45 percent in just 2020 alone. Public opinion on war historically doesn’t matter for Washington, but there is some “sense that you’ll be accountable if you vote for war as Clinton did in 2008,” Center for Defense Information Director Mandy Smithberger points out. Conservatives are thoroughly persuaded by messaging that China is the aggressor. Liberals, who may be a little more wary of another forever war, generally respond better to messaging around China’s numerous human rights violations.

As the granddaughter of a teacher tortured in the Cultural Revolution and as someone who has organized her whole life to abolish police, detention, and incarceration, I refuse to defend China’s human rights record. I will also point out the obvious: Wars rarely fix human rights issues. What may begin as a so-called “humanitarian war” (if that even exists) naturally devolves into a general war. What follows is family separation, torture, rape, famine, destabilized communities, and economic precarity. And the U.S. has a long history of violent imperialism, justified by Cold War ideology, in the Asia-Pacific: Korea in 1950, Vietnam in 1955, Laos in 1959, Indonesia in 1965, and Cambodia in 1968, comprising at least 10 million in casualties.

This country has a quarter of the world’s incarcerated population, most of them Black, and thousands of detainees in camps subject to sexual violence and coerced sterilizations; this country selectively enforces enemy nations’ but not allied nations’ human rights violations; this country’s military has killed, raped, and tortured abroad—these hypocrisies seem lost on voters, even liberal Democrats. Today, 70 percent of Americans want the U.S. to confront China over its human rights policy.

During World War Two, Chinese Americans experienced a strange Yellow Peril flip. Two weeks after Pearl Harbor, Time magazine published the article “How to Tell Your Friends From the Japs.” Suddenly, Chinese Americans were “loyal, decent allies” and the Japanese were “evil spies and saboteurs.” It turns out Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have always been pawns to be leveraged in American foreign policy.

Today, as Washington cynically promotes Yellow Peril as a strategy to pass major legislation at home and retain America supremacy abroad, we Asian American and Pacific Islanders can expect an increase in surveillance, harassment, and attacks. President Biden condemning hate crimes doesn’t change that. So while the federal government continues to sell its war on China, I fear the coming violence against our communities in this country and in the rest of the world. This AAPI Heritage Month, I fear for my family members’ lives.