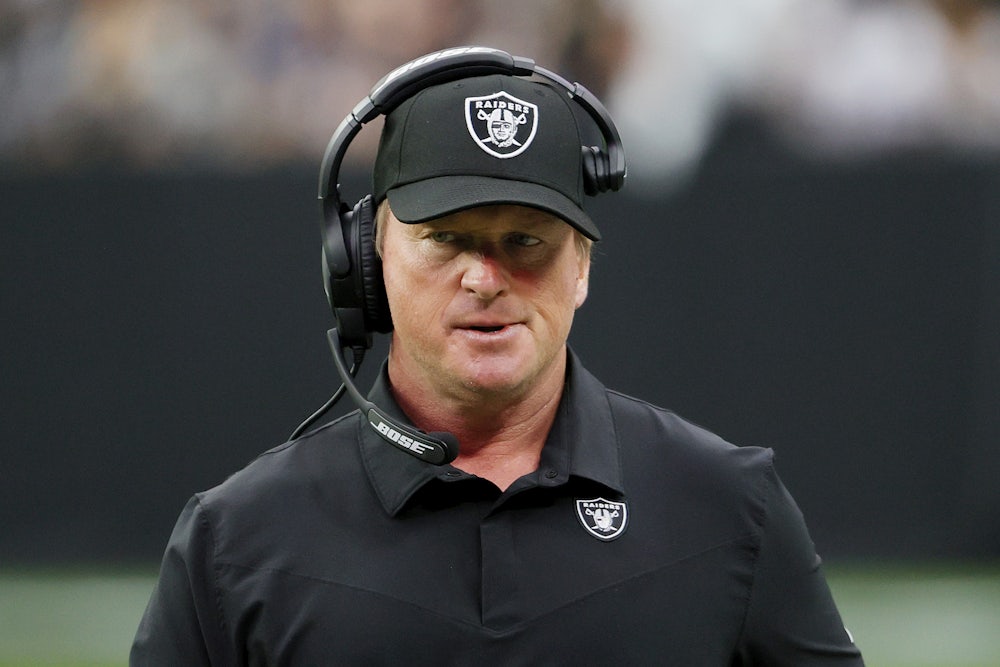

Speaking to reporters on Sunday evening, two days after 10-year-old emails in which he used a racial trope when referring to DeMaurice Smith, the head of the NFL Players Association, Las Vegas Raiders coach Jon Gruden insisted there was nothing left to talk about. “I’m not gonna answer all these questions today,” he said shortly after the Raiders lost to the Chicago Bears. “I think I’ve addressed it already. I can’t remember a lot of the things that transpired 10 or 12 years ago, but I stand here in front of everybody, apologizing. I know I don’t have an ounce of racism in me. I’m a guy who takes pride in leading people together, and I’ll continue to do that for the rest of my life. And again, I apologize to De Smith, and anybody that I have offended.”

Gruden was ready to move on—and so, it seemed, was the NFL. The Raiders coach was arguably past his prime; he won his last Super Bowl in 2003 and spent much of the 2010s in the broadcast booth. But he was safely ensconced in year three of a record-breaking 10-year, $100 million coaching contract and the beneficiary of deep connections from decades of experience in the league. With his contract and his connections safely in hand, it looked for all the world that Gruden was going to see this through.

His career trajectory underwent a rapid reversal on Monday evening, after The New York Times published several other emails Gruden had exchanged as part of a thread with Bruce Allen, who was then the general manager of what is now the Washington Football Team, as well as several business figures, including the CEO of Hooters. In these missives, Gruden referred to Roger Goodell, the NFL commissioner, with an anti-gay slur and as a “clueless football pussy,” and accused the league of forcing the St. Louis Rams to draft a gay player for P.R. purposes. In other emails, Gruden mocked female referees and suggested that NFL players should be terminated for kneeling during the National Anthem. The emails also included photos of scantily clad Washington cheerleaders. (Gruden’s younger brother, Jay, served as Washington’s coach from 2014 to 2019; the organization has been accused of maintaining a toxic workplace amid a myriad of sexual harassment scandals that preceded his tenure as coach.) Not long after the Times investigation was published, Gruden resigned.

There have been half-hearted attempts on the right to deride this all as yet another example of cancel culture and wokeness run amok—a “But his emails” situation of sorts. But as Will Leitch noted in New York magazine, Gruden would have almost certainly been run out of the game a decade ago when he was a far more prominent figure if these emails had come to light. Instead, they reveal the deep cultural rot at the center of the NFL and just how far the league still has to go to fix it.

Gruden’s own prominence is central to this scandal. Although his three years in Las Vegas have been mediocre at best, he is nevertheless one of the best-known figures in professional football. In the early 2000s, he was arguably the poster child for the NFL’s new breed of innovative young coaches and one of its instantly recognizable faces. Impish, he bore a distinct resemblance to Chucky of the Child’s Play series, a nickname that has stuck with him for decades. He won his first Super Bowl at age 39; when his career stalled out, he spent eight years as one of ESPN’s most important figures, co-hosting its flagship program, Monday Night Football.

Gruden’s role within the ESPN Extended Universe was that of the network’s on-call coach: He hosted, for instance, Gruden’s QB Camp, where he worked with young quarterbacks. Above all, he was the audience’s stand-in for the coaches on the field who were making the calls on which he was commenting. It was during his tenure at ESPN that Gruden sent the emails that ultimately cost him his second act as an NFL head coach. (Gruden still has deep connections at the network. Not long after Gruden spoke to the press on Sunday, ESPN’s Mike Tirico and Tony Dungy, himself a former coach, leapt to his defense, using their perches on the network to insist he wasn’t racist—or at least that he had never been racist around them.)

Gruden’s swashbuckling, imperious manner has taken a hit in Las Vegas, but it’s on full display in the leaked emails: Here is someone showing you again and again who they are, with no fear of consequence. He is speaking as arguably one of the NFL’s most important voices to one of its general managers and showing exactly what he thinks about women, Black people, and members of the LGBTQ community. These emails were zinging around even as the league ramped up its effort to appeal to a broader audience and take its macho image down a notch. In them, Gruden demonstrates an unalloyed contempt for this mission. Or to put it another way, Gruden’s retrograde opinions, and their wide acceptance among those with whom he shared them, illuminate the extent to which those efforts are a sham, a weak and half-baked attempt at reforming an institution that has no sincere interest in the changes its marketing campaign pretends to take seriously.

There is an element of P.R. in Gruden’s firing, as well. His gargantuan contract may have seemed like job security, but the Raiders are a relative nonentity on the NFL’s power rankings. The league has made deep investment in its attempt to keep up appearances as an open and inclusive league; in recent years, the NFL has decorated its stadiums with “End Racism” banners and embedded similar messaging within its broadcasts. Even though the league was well aware of Gruden’s emails before they leaked, it now, as Slate’s Alex Kirshner wrote, won’t have to “publicly square” his continued employment with its various social justice campaigns.

Gruden may currently be the coach of a not very good football team, but his influence is everywhere: He has been an NFL head coach in three different decades, has worked for the league’s most important broadcast partner. Even after his emails came to light, the NFL looked the other way. After they were leaked, ESPN underplayed its coverage and allowed its top talent to defend Gruden. Given the weak response from both entities in this broadcast partnership, it’s hard not to conclude that Gruden was right to feel like he was bulletproof, free to say whatever he wanted with impunity—at least until it all became too much to ignore.

There is more to come here, though this story’s next phase may not involve Gruden. These emails were uncovered as part of an investigation into the Washington Football Team’s well-documented misogynistic and toxic culture—yet another of Gruden’s many connections to the wide world of football. That investigation, should the NFL dare to release it, could be damning, not just about the conduct of senior employees and the owner of that franchise but of how the league treats reports of harassment and abuse. The league has weathered all sorts of storms that might capsize other, less guarded and plutocratic institutions—from its mishandling of multiple instances of domestic violence among players to the boundless evidence that the sport’s dangers are destroying the lives of its participants. Gruden’s emails suggest that there may be more damning uncovered secrets about a wayward and broken culture yet to come.