Even amid economic and social change, eras in pro sports are typically defined by excellence on the field or in the arena. This is generally a good thing for leagues trying to sell fans on the mythology of athletes and their feats. Over the past few generations, the National Football League has excelled at keeping its fans focused on the field, and to great reward. The league’s revenue has grown 31 percent since 2009, and the average NFL team is worth more than $1 billion. (For years I helped feed those myths, as a producer at NFL Films.)

But of late, the league and Commissioner Roger Goodell have failed to keep fans from noticing the harms of the game.

Players committing domestic violence, sexual assault, and child abuse have sullied the league’s image. And even these crimes have yet to supplant the league’s central controversy: The violence of the game—largely its reason for being—leaves its players with head trauma, mental afflictions, and shortened lives. Given the effect brain injuries have on those around players, too, the calculus for NFL risk has changed forever. We need look no further for evidence than the 2013 murder of Kasandra Perkins by her boyfriend, Jovan Belcher, a Kansas City Chiefs linebacker who after his suicide was found to have suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

The information we have about CTE in the brains of deceased players has increased exponentially. Dozens of recent retirees, including Tony Dorsett, Bernie Kosar, and Brett Favre, have been diagnosed with CTE or are showing signs of the disease. And a massive 2013 court settlement, awarded to 5,000 players and their estates after they alleged that the league hid the dangers of concussions, may still grow.

So if you want to argue that NFL players “knew what they were getting into,” that settlement is evidence that, in a previous era, they had no idea. That’s changing. The dangers are now so openly acknowledged that “Would you let your kid play football?” has become a real question in a nation that regards the NFL as civic religion.

Something happened Monday, however, that should signal to the NFL that it must do more than reduce risk to protect its players. It must help to redefine the toxic masculinity that still pervades the heads it seeks to protect.

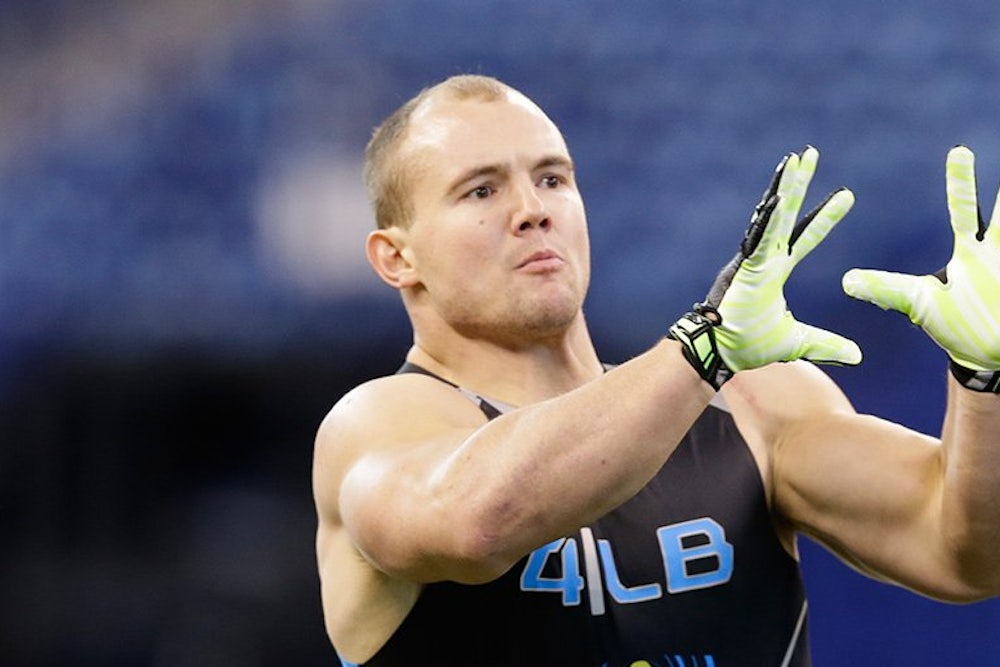

Chris Borland, a 24-year-old linebacker who starred as a rookie for the San Francisco 49ers last season, told ESPN’s Outside the Lines that he is retiring after only one season. The shocking thing isn’t the retirement of a terrific young player who would’ve inherited a starting job from potential Hall of Famer Patrick Willis, who retired this month because of a lingering toe injury. It’s the fact that said player retired because of all he’s learned about degenerative brain diseases—and did so without any significant concussion history. Borland shows what can happen when players assess the new facts and prioritize their health above the game.

Grantland’s Bill Barnwell wrote Tuesday that he couldn’t find another case of an NFL player making this kind of proactive departure. Despite Borland being an island, this feels like a tipping point in a way no other younger player retirements have. Undoubtedly players will arrive to fill Borland’s shoes, but I agree with what former NFL wide receiver Donté Stallworth told me Tuesday. “I don’t think there’s going to be this mass exodus of guys leaving the NFL—that’s just not going to happen,” said Stallworth, who is now a National Security Fellow at the Huffington Post. “But what I do believe is going to happen is that you will see more of the older guys not taking the extra two or three years they may have thought they wanted to play early in their careers.”

Less a sign of where the NFL is heading, Borland signals where it has already been going: players, knowing the risks, trading shorter careers for longer lives. A former NFL veteran who played for more than a decade, speaking on condition of anonymity, told me Tuesday that Borland is both the fruit of past labor and an indicator that NFL players themselves are changing. “It’s a different type of kid that’s playing now,” he told me. “We all fought for today’s player to understand his value in society, to be more than a piece of meat.”

He did, however, echo concerns about Borland’s desire. “I question whether or not this guy wanted to be a football player to begin with,” said the former player. “This isn’t the pre-2011 practice rules. This is a risk that we’re all aware of.” Former player and current 49ers radio analyst Tim Ryan put the matter more bluntly on Tuesday, saying that while Willis retired, Borland “quit.”

This is the macho culture that needs to die for the NFL to continue to thrive in an information age. When machismo turns to masochism, it destroys young men.

Look no further than Stallworth’s friend Sidney Rice, who ended his career before last season at the age of 27 because of repeated brain injury. Speaking to CBS News, the former Seahawks and Vikings star expressed concern about his own health and about the culture surrounding concussions. “My story is unique because I’m willing to talk about it,” Rice said. “A lot of the guys don’t talk about it, they don’t speak about it. They go, they play, [they’re] done and that’s that. If we continue along that path then what kind of example are we setting for the youth that’s coming along?”

The NFL is trying to steer youth the right way on the field, at least. Many concussions result from poor-form tackling, so the league launched its Heads Up Football movement in 2013 to teach proper technique to coaches and young players, along with better concussion response and heat and hydration preparedness. According to the 2014 Health and Player Safety Report, about 5,500 youth football organizations were signed up for the initiative at the start of last season.

Technique matters, but so do demographics. Does Borland, who has a history degree from the University of Wisconsin, point toward a day when the NFL’s labor pool will come exclusively from players who, unlike him, cannot afford to forfeit millions? Green Bay Packers president/CEO Mark Murphy said that’s already happening. “There is an argument that you’ve probably heard, that eventually all football players are going to come from poorer backgrounds,” Murphy told ESPN’s Kevin Seifert. “It’s that way a little bit now, for whatever reason.”

That reason, I’d argue, is that financially stable players have more options after college. Or the risks may have prevented them from pursuing football in the first place. In protecting his health, Borland did what wealthy and protective parents have been doing now for a while. Other kids, who feel the NFL is their only path out of poverty, will continue to play and to expose themselves to danger.

I say that not to discourage them; plenty of players emerge from their careers with good cognitive health, and many in the largely black labor force are able to build new wealth. But even with all the information available, Borland still has to hear people like Ryan calling him out for prioritizing his brain. Others don’t consider it manly to share stories, as Rice is doing.

We need to stop making manhood about tearing ourselves apart. Forget about more players retiring early, fixing tackling form, or the labor pool shrinking. If the NFL doesn’t cut out this macho crap, it’ll still be the same game—profitable, yes, but forever grinding up men like pieces of meat.