On a Friday in early June 1941, Richard

Wright addressed the opening session of the Congress in Defense of Culture in New

York City. “Some of you may wonder why a writer, at a congress of writers,

should make the theme of war the main burden of a public talk,” he began. He explained

that it was for the simple reason that few things mattered “one-half as much.” Then

he laid out his case against American involvement in World War II, claiming that

the country’s intervention was not likely to change the outcome, that peace was

the most radical course of action, and that Black Americans had no reason to fight

on behalf of a country that denied their humanity. “Our primary problem,” he

said, is “a problem concerned with the processes of democracy at home.”

World War II has since been historicized as a clash between God and the devil, but as Wright was speaking—after the London Blitz but before the bombing of Pearl Harbor—America’s potential involvement was much debated. A majority of the country supported it by the time of Wright’s speech, but the isolationist right and the ideological left remained opposed.

Wright’s message, in that case, was welcome at the Congress—an event organized by the League of American Writers, a group with close ties to the Communist Party. His speech was so well received, in fact, that the party-aligned New Masses published his remarks in full in its June 17 issue that year. When the magazine went on sale, newspapers across the country quoted from Wright’s speech, making him, suddenly, a prominent opponent of the war. And then, just as suddenly, that became a very treacherous thing for him to be.

About a week after Wright’s speech circulated, Germany invaded the Soviet Union, ending their nonaggression pact and the Communist Party’s rationale for neutrality. When Wright heard the news, he called the executive secretary of the League of American Writers and asked: “What do we do now?” The answer was soon clear. In short time, Communists the world over stopped opposing the “imperial war” and began supporting the “people’s war.”

Before Wright’s next speech, Communist Party functionaries pressured him to change his position on the war. He declined but stopped short of insubordination. (When he spoke, he discussed his obligations as a writer and said nothing about the war.) It wasn’t the first time he had felt betrayed by the party, but it was the cut that reached closest to the bone. According to Wright biographer Hazel Rowley, “An irreversible gulf had opened between [them].”

Wright’s connection to the Communist Party had been at the center of his intellectual, artistic, and social life for years. He believed in its message of class unity. Some of his earliest serious writing was published in magazines the party supported, and he wrote for The Daily Worker while completing his first book, Uncle Tom’s Children. Much of his social circle had been assembled from the party’s ranks, and he and his wife, Ellen Wright, were both active members. Breaking with the party would mean losing friends and allies and part of his identity, while gaining a great many enemies. But Wright was prepared to do it. The military draft was a looming threat for him. And he would never support the war or encourage Black men to fight on America’s behalf in a segregated Army.

There was no way for Wright to know how the war would proceed, what the party would ask of him, and whether he would be forced to defy it. Amid all that uncertainty, he turned his attention to the composition of a new novel.

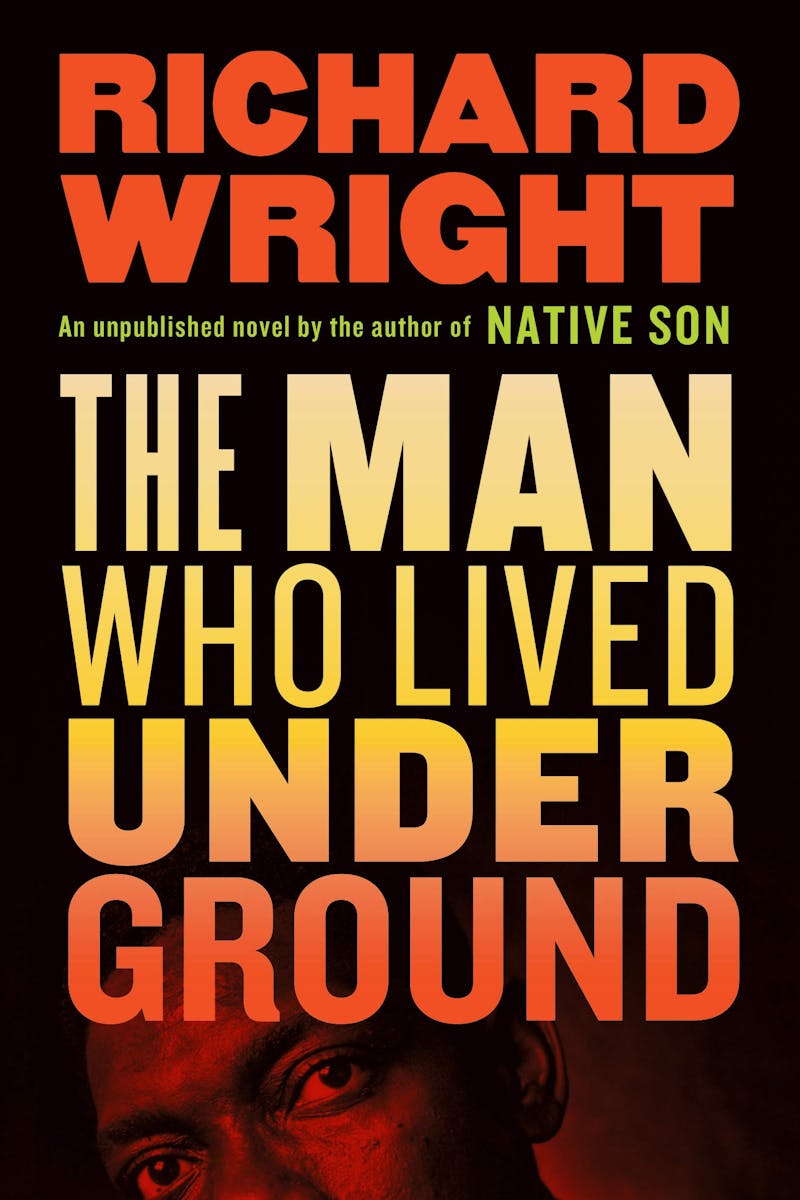

When Wright gave his speech, he had been working on a book titled Black Hope for about two years. It was an ambitious, naturalistic novel that readers were likely to accept as the anticipated follow-up to Native Son. But the following month, he set it aside and began writing a new book, a meditation on isolation, survival, and the ability of faith to make sense of the world’s chaos and predations. He called it The Man Who Lived Underground, and it is being published in full for the first time this month by the Library of America.

Wright worked on his manuscript primarily in his Brooklyn apartment at 11 Revere Place. He used an Ediphone—a recording device that etched a simulacrum of his voice onto a spinning wax cylinder when he spoke into its handset—to narrate his story, then edited his work by playing it back and revising as he listened. And the effect of that process can be heard in the text, which strides forward with the hurried rhythm of someone speaking to themselves aloud.

The Man Who Lived Underground is constructed of the precise, often terse, sentences that are a hallmark of Wright’s work, and its prose, thrumming with energy, has many pleasures to offer. Its story, in contrast, contains none. Simply put, it’s a work of horror.

The book’s protagonist is Fred Daniels, a Black man employed by a white family named Wooten. He is short, trim, and unremarkable—a person of faith, an expectant father, and, in every sense of the word, an innocent. When he feels threatened, he invokes the symbols of his rectitude and trusts they will save him: White Rock Baptist Church, Wooten, Reverend Davis, Sunday School, Glee Club, pregnant wife.…

But the trouble that finds Daniels is a base, elemental sort of evil that cares nothing for the quality of his soul. It appears in the form of three police officers—Lawson, Johnson, and Murphy—and to them, Daniels is just a “boy.”

The officers pick Daniels up on a Saturday afternoon and accuse him of murder. Their evidence: He is Black, and he was near the crime scene. This is enough to convince them of his guilt, so when he pleads innocence, they berate and torture him. Eventually, inevitably, Daniels signs a confession that he played no role in composing and is too shaken to read.

These events pass quickly—within the first 30 of the novel’s 150 pages—and it’s afterward, when Daniels slips away from his captors, that Wright’s story properly begins.

Daniels flees into the city’s sewers, where darkness engulfs him. By matchlight, he navigates fetid tunnels, rushing waters, and horrors swept from the streets of the world above—a gauntlet that cleanly divides his life. Within hours, he begins thinking retrospectively about “the life he had once lived aboveground.” And when the sound of religious song reaches him in the underworld, he pities the singers for their “defenseless nakedness” and disowns them and their faith. He rarely thinks about his family.

Daniels discovers a cavelike redoubt deep in the earth and claims it for his own. Then, when he’s safely hidden and unburdened by the cloistering gaze of white society, the scales fall from his eyes. The irrationality of the violent world he fled becomes clear, and the symbols of wealth that dictate the rhythms of life above ground seem laughable.

Liberated, Daniels embraces his new freedom and indulges his curiosity. He slithers through tunnels and bores through walls to access spaces (a storefront, a theater, a jewelry shop, and others) he would not have been permitted to enter—and while occupying them, he takes freely. He steals a typewriter, lugs it back to his cave, and taps out the lengthy conjunction: itwasalonghotday. He has never touched a typewriter before, and when he intuits how it operates, he retypes the same sentence in accordance with the rules of grammar.

Satisfied, he speaks to the void surrounding him: “Yes, I’ll have the contracts ready tomorrow.” And then he laughs. “That’s just how they talk,” he says, turning the performance of respectability into a derisive joke.

He continues his explorations and thefts, and before he has finished, he has papered his walls with stolen cash, strewn diamonds on the ground, and hung golden rings and pocket watches from the walls. His new home becomes a monument to his rejection of the mores he once embraced. “[B]etween him and the world that had rejected him,” Wright wrote, “would stand this mocking symbol.”

Daniels would have considered these actions sinful in his previous life, and, briefly, doubt grips him. But he indulges it for only a moment. “[I]f the world as men had made it was right, then anything else was right, too,” he thinks. “Any action a man took to satisfy himself—theft or murder or torture—was right.”

That bold existential assertion sets Daniels apart from Wright’s earlier protagonists. In a lengthy essay meant to accompany The Man Who Lived Underground, Wright explains the character’s genesis and his purpose in creating him. The novel, he says, was written as an exploration of his grandmother’s religious convictions. This woman, Margaret Bolden Wilson, was a Seventh-day Adventist who would have been considered abstemious even by the most devout. She abided no written word but the Bible, cared nothing for social niceties or organized society, and burned library books when she found them in Wright’s room. She was, he says, “ceaselessly, militantly at war with every particle of reality she saw.”

Wright thought of Bolden as maddening and inscrutable. But in The Man Who Lived Underground, though he remains sober about the limits of faith, he finds meaning in her desire to set herself apart from society. In his telling, Daniels is hapless but content before his arrest, then freer when he descends into the sewers and forsakes his faith but also adrift and lonesome. Neither life offers a full measure of humanity, but he survives both and doesn’t face his greatest peril until he develops a desire to confess his new crimes and emerges from the sewers.

Wright’s essay, “Memories of my Grandmother,” is a searching and earnest piece of prose that explains much about what he was trying to accomplish with his novel. But it says little about why he wrote the book when he did, at a time when his publisher believed he was writing a different one, and only weeks after proclaiming that few issues were more important than the war. And I like to think that he was drawn to the riddle of his grandmother’s religiosity as his faith in the Communist Party was faltering.

Wright’s relationship to the party continued to deteriorate as he worked, and soon after he completed his novel, he withdrew from his formal responsibilities. As he broke with the Communists, he must have been alert to the benefits and the shortcomings of that association and to the parallels between the role his beliefs had played in his life and the role his grandmother’s had played in her own. The party, like the church, offered Wright a means of making sense of the world, as well as a feeling of belonging—but it, like the church, was an imperfect shield. It does not seem coincidental that, when Fred Daniels emerges from the sewers at the end of The Man Who Lived Underground, he must face both violent police and the terror of air raid sirens and war planes dropping bombs on American soil.

The Man Who Lived Underground is a much different book from Native Son. The latter is the work of an architect raising a monument skyward on a foundation of physical and psychological observation, while the former reads like a fable: digressive, improbable, and enthralling. Making that shift involved the risk that readers would abandon Wright, but he could accept that. He called the book a work of “inspiration” and saw it as a chance to break new ground. This is “the first time,” he told his agent, that “I’ve really tried to step beyond the straight Black-white stuff.”

Wright submitted his manuscript at the end of 1941, about six months after he began writing. Soon afterward, his editor, Edward Aswell, rejected it.

So far as the extant record shows, Aswell’s reasons were obscure. But readers’ notes penned to a surviving copy of the manuscript suggest two explanations.

The first is that the novel is uneven, a clash of naturalistic writing and allegory. There’s some justification for this complaint. The book’s dialog is sometimes flat, Daniels’ psychological shifts stretch credulity, and time expands and contracts oddly throughout. But those shortcomings are not justification enough for a rejection. The author of Native Son could be forgiven for the novel’s minor sins a hundred times over.

The more likely cause is the book’s premise. One reader noted that its depiction of police brutality was “unbearable,” and Aswell would have had to consider whether white readers were likely to purchase a book featuring a realistic depiction of officers abusing an innocent Black man. He would have been justified in having doubts, cynical though they were. As recent history has shown, even when the police are captured on tape committing murder and the plain evidence of their crimes is available to all, scores will choose to doubt their own senses.

You could say that the book’s release now is timely, given that it contains an account of police torture. Last week, 20-year-old Daunte Wright was killed by a police officer at a traffic stop in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota, just 10 miles away from where Derek Chauvin is being tried for the murder of George Floyd.

But that feels false because Wright’s story would have been just as relevant if it had been released 10 years ago or 30, 50, or 80—when he composed it. The brutality of American racism and police violence, and the deep need people feel to embrace faith or ideology as a means of gathering the strength to resist those predations, have been integral parts of American life since before Wright committed his story to the page.

Maybe, then, it’s more accurate to think of The Man Who Lived Underground as timeless rather than timely.