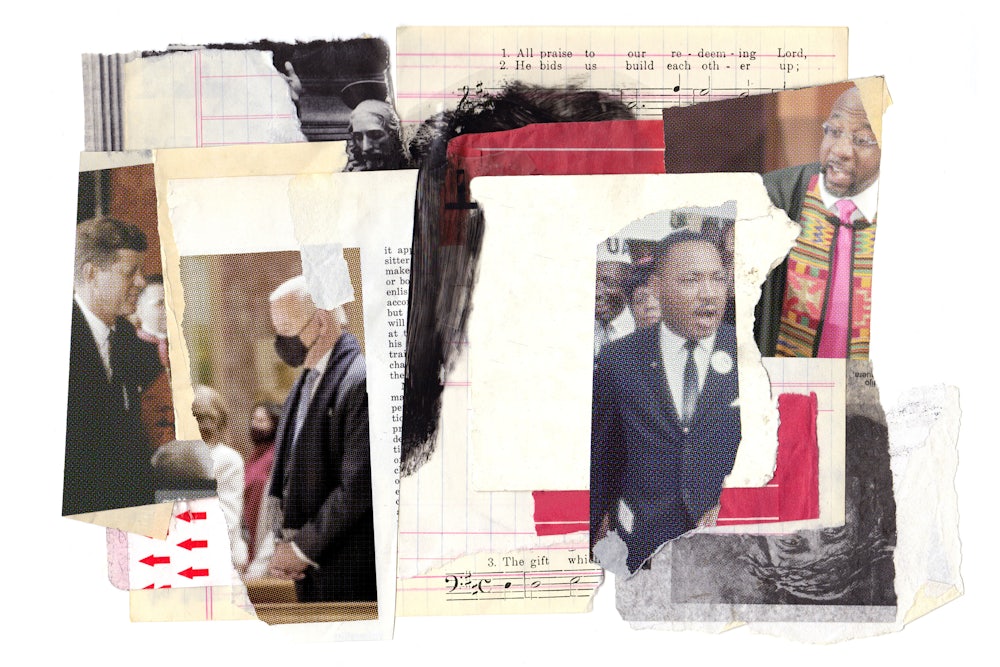

No one who watched the inauguration of Joe Biden could have missed that he was a Roman Catholic. Before the day’s public ceremonies, he attended a private Mass at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle, named for the patron saint of civil servants. Then, at the Capitol, a Jesuit priest and former president of Georgetown University, Father Leo O’Donovan, used an otherwise ecumenical prayer to remind the audience that a Catholic had asked for God’s blessing for George Washington’s inauguration. When Biden took the oath of office, he placed his left hand on a century-old family Bible emblazoned with a Celtic cross, and, after he was sworn in, he gave an address that borrowed from both Scripture and Catholic tradition. “Many centuries ago, St. Augustine, a saint of my church, wrote that a people was a multitude defined by the common objects of their love,” he said. “What are the common objects we love that define us as Americans?”

The answers Biden gave—a somewhat perfunctory list that included “opportunity” and “security”—were less striking than the question he posed, which stood out for its unembarrassed particularity. It was not just an obligatory invocation of a benign Supreme Being, the kind of bromide that has often accompanied our civic rituals.

Biden came of age during an auspicious time, religiously speaking. Reared in the last vestiges of an Irish Catholic immigrant culture, he would have heard the Latin Mass into his twenties, then lived through the reforms of the Second Vatican Council—he entered adulthood as Catholics entered the American mainstream, a period Garry Wills called the reign of “the two Johns” (Pope John XXIII and John F. Kennedy). Villanova University theologian Massimo Faggioli, in his new book, Joe Biden and Catholicism in the United States, suggests that Biden’s faith still bears the mark of these origins. “Biden is the first Catholic president to publicly express a religious soul,” he writes, “not a vaguely Christian, but a distinctly Catholic one, confidently but not bellicosely.”

That was apparent during Biden’s campaign against Donald Trump. Biden, for reasons of both temperament and ideology, was probably always going to run on a message that included “unity” and “healing.” During the Democratic primaries, he would reminisce about the way Washington used to work and tout his record of hammering out legislative deals with Republicans. But as the pandemic unfolded and he won his party’s nomination, Biden’s emphasis shifted, and the significance of his Catholicism to his candidacy deepened. He portrayed himself as an alternative to Trump’s incompetence and cruel disregard for human life—a man of decency and empathy, a claim inextricably tied to a biography marked by profound suffering and grief. Biden had buried a wife and daughter early in his political career, both killed in a car accident, and, more recently, a son cut down by brain cancer. Now he was pursuing the presidency amid mass death.

It was a crisis to which Biden brought unique capacities. Perhaps no American politician has had to mourn as often and as publicly as him, a fate that’s meant his Catholicism could never be merely private. (As it happens, his closest rival for this sad designation is another Catholic, Ted Kennedy.) Biden’s intimacy with loss made him a prominent and painfully sincere eulogist over the years—our nation’s “designated mourner.” The journalists Paul Moses and Michael Connor have emphasized that, traditionally, this was an important part of an Irish Catholic politician’s job, and that Biden draws deeply from that culture in his fulfillment of it. “His eulogies are built on themes of redemption and forgiveness,” Moses and Connor write, “as well as amazement at the dignity of each human being.” When Biden spoke about families who now had an empty chair at the kitchen table, he did so with credibility. He spoke out of his own sorrow—sorrow that he’s movingly testified his Catholic faith helped him endure. When his son Beau died in 2015, a grieving Biden called upon O’Donovan to preside over the funeral Mass.

Every so often, the “religious left” breaks through as a topic of fervent interest, a story that draws attention from beyond the reporters dedicated to the religion beat. Usually this has something to do with the fortunes of the Democratic Party, most of all the performance of its presidential candidates. In celebration, the deft use of religion receives a fair share of the credit—proof that talking convincingly about God can help overcome the party’s reputation as a bastion of out-of-touch coastal elites. In defeat, some blame inevitably falls on a supposed lack of faith-based appeals in campaign messaging, or a failure to make religious outreach a higher strategic priority—devoting resources to sway Midwestern Catholics, suburban evangelicals, or “moderates” for whom churchgoing is a comforting signifier.

Such a tendency shouldn’t be surprising. Going back to the religious boom of the 1950s, American political leaders have consistently reached for religion as a sort of all-purpose social fixative: a bedrock, shared faith in, well, the idea of faith. Civic religion supposedly helped underline America’s core difference with its Cold War rival, the Soviet Union—our embrace of religious freedom, in this telling traced all the way back to the Puritans, stood in stark contrast to the oppression of atheistic global communism. President Dwight D. Eisenhower summed up this vague consensus in 1952, with his pronouncement that “our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.” For decades, that anodyne, patriotic piety has lingered as part of the language of presidential leadership, including Barack Obama’s rhetoric—the kind of sentiment expressed by invoking the “awesome God” of blue states rather than channeling Jeremiah Wright’s righteous wrath.

But after Donald Trump narrowly defeated Hillary Clinton in 2016, a different kind of debate about the religious left emerged, one that had less to do with merely winning the next election or the unifying force of civic faith. That older consensus had long been buckling under the stress of historical trends, anyway: the decline of the mainline Protestant denominations; the rise of conservative evangelicals; the culture wars over abortion, gender, and LGBTQ rights; secularization and political polarization. For years, surveys have shown that a growing segment of Americans didn’t identify with any formal religious tradition at all—the so-called (and much discussed) nones, who skewed young and leftward. Meanwhile, whether voiced as revulsion toward Obama or adulation of Trump, the religious right became more extreme in its politics and more unyielding in its ardor for cultural fights.

The grand reverie of trans-faith communion was no more, and religion now seemed to bring the sword more than peace. Left-leaning people of faith played an essential role in the resistance to Trump; that alone led to an increase in the attention they received (even if they had been doing such work for years). The religious left, whatever else might be said about it, has often found purpose in protest, and Trump’s odiousness particularly antagonized believers on the left—from winking at antisemitic conspiracy theories on the right to his ban on Muslims entering the United States. At 2017’s deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, clergy were there, linked arm in arm, protesting against the city’s invasion by white supremacists.

Other possibilities followed from a surge of interest in democratic socialism: What the left in “religious left” denoted suddenly took on new meaning. Bernie Sanders’s challenge to Clinton in the Democratic primaries had opened up a more radical political horizon, a cause that found unexpected allies—not least Pope Francis, who had excoriated trickle-down economics and dedicated an encyclical to the moral necessity of combating climate change. For the first time in a long time, genuine ideological alternatives to neoliberal austerity seemed to be gaining, and they were backed by the most prominent leader of the world’s largest religion. When Sanders, a few days before the 2016 New York primary, spoke about labor rights at a Vatican conference convened for the twenty-fifth anniversary of John Paul II’s social encyclical, Centesimus Annus, it provided a glimpse of the way religion could be an ally in the fight against an economic order that killed.

These developments didn’t come out of nowhere. Well before the advent of Trumpism, there were hopeful signs of a renewed spiritually minded sensibility on the left, particularly within Black churches. The Reverend William J. Barber II of Goldsboro, North Carolina, the former head of the state’s NAACP chapter, launched his “Moral Mondays” protests at the state’s General Assembly building in 2013. And the Reverend Raphael Warnock, now best known as one of the two senators elected in January’s Georgia runoff election to tip majority control of the chamber to the Democrats, had for over a decade held Martin Luther King Jr.’s former pulpit at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church. Like Barber, Warnock has preached an urgent social-gospel message—combining calls for Medicaid expansion and police reform with grassroots voter registration drives, including those captained by his state’s former Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams. (It’s not for nothing that the voter suppression legislation recently approved by the state legislature in Georgia targets Sunday early voting for elimination—Sunday voting is one of the most powerful engines of Black turnout.)

There would also appear to be new opportunities, as the fallout from Trump’s presidency continues, for a religious left to welcome evangelical believers migrating away from their home denominations. Just this March, for example, Beth Moore, the bestselling Southern Baptist inspirational author and Bible teacher, announced she was leaving the denomination. Moore had broken with some of her fellow evangelicals over their embrace of Donald Trump in 2016; once the notorious Access Hollywood tape documented the presidential hopeful boasting of past sexual predations, Moore declared that it smacked not just of immorality but outright “sexual assault.” As she came gradually to speak of her own past sexual trauma, Moore said she felt the Southern Baptist faith no longer represented a safe place for such conversations, even though she believed the denomination had “saved her life.” The Southern Baptists are also facing high-profile defections among Black clergy, ever since the denomination followed the lead of the Trump administration and announced a purge of “critical race theory” within its ranks.

Even these stirrings, however, reveal something other than unambiguous gains for the religious left. Jack Jenkins, author of the recent book American Prophets: The Religious Roots of Progressive Politics and the Ongoing Fight for the Soul of the Country, consistently emphasizes that the religious left shouldn’t be understood as a mirror image of the religious right. While the latter certainly has had to work to forge alliances between conservative Catholics and conservative Protestants, it remains mostly Christian and mostly concerned with a distinct set of social issues. But the religious left, as Jenkins puts it, is a “coalition of coalitions”—both more diverse and more diffuse than the religious right.

Jenkins’s exhaustive reporting in American Prophets bears out his claim that the religious left is “amorphous” and “ever-changing,” without anything like a single agenda or set of priorities to unite it. American Prophets begins with a deeply sourced account of the Obama administration’s fight to pass the Affordable Care Act, and the decisive role played by the Catholic Health Association’s Sister Carol Keehan in making it happen—a story of power and persuasion at the highest levels of government. From there, Jenkins ranges widely in providing a tour of the religious left today: anti-pipeline protests at Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, which drew mightily from a non-Western brand of religious witness; the chaplains of the Occupy movement; sanctuary churches shielding undocumented immigrants from deportation; and pastors who played a role in Black Lives Matter, religious socialists, LGBTQ believers, and eco-friendly Buddhists.

This points to one of the persistent challenges for the religious left: navigating such a motley assortment of faiths while recognizing that spiritual sustenance and political perseverance often come from plumbing the depths of a tradition. The poet Christian Wiman argues that “the only way to deepen your knowledge and experience of ultimate divinity is to deepen your knowledge and experience of the all-too-temporal symbols and language of a particular religion.” This is not a problem for the religious right, really—no one doubts that at its center are white Christians, whatever other differences exist in its ranks. Not so for the religious left.

Take Warnock’s recent election. If it supplies one inchoate model for the religious left—a mustering of traditional liberal party activists alongside a newly mobilized religious Black electorate—it also has clear limits. Warnock’s spiritual appeal is rooted in a particularistic faith that can’t necessarily scale up into a force capable of wielding the influence of the sunny (and socially indifferent) Eisenhower consensus. When he invoked the mandate to believe more-or-less anything, Eisenhower was able to exploit a freestanding ecumenical movement led by the Protestant mainline—even as Will Herberg’s 1955 study Protestant Catholic Jew posited these three major Western faith traditions would (for good and ill) remain in tension with the broad civic inculcation of a single, generic brand of religiosity in postwar America.

A campaign like Warnock’s, by contrast, took place in the midst of religious fragmentation and disaffiliation—the rise of the nones, the spiritual but not religious. This is another difficulty for the religious left. As a report at FiveThirtyEight explained, “The Democratic coalition isn’t dominated by a single religious group. And Democrats don’t prioritize religion the way Republicans do—in fact, the Democratic Party has been growing steadily less religious over the past 20 years.” Put differently, the religious left not only has to contend with its own remarkable diversity, but has to operate in tandem with a broad liberal left that is rapidly secularizing, or at least becoming more spiritual than religious.

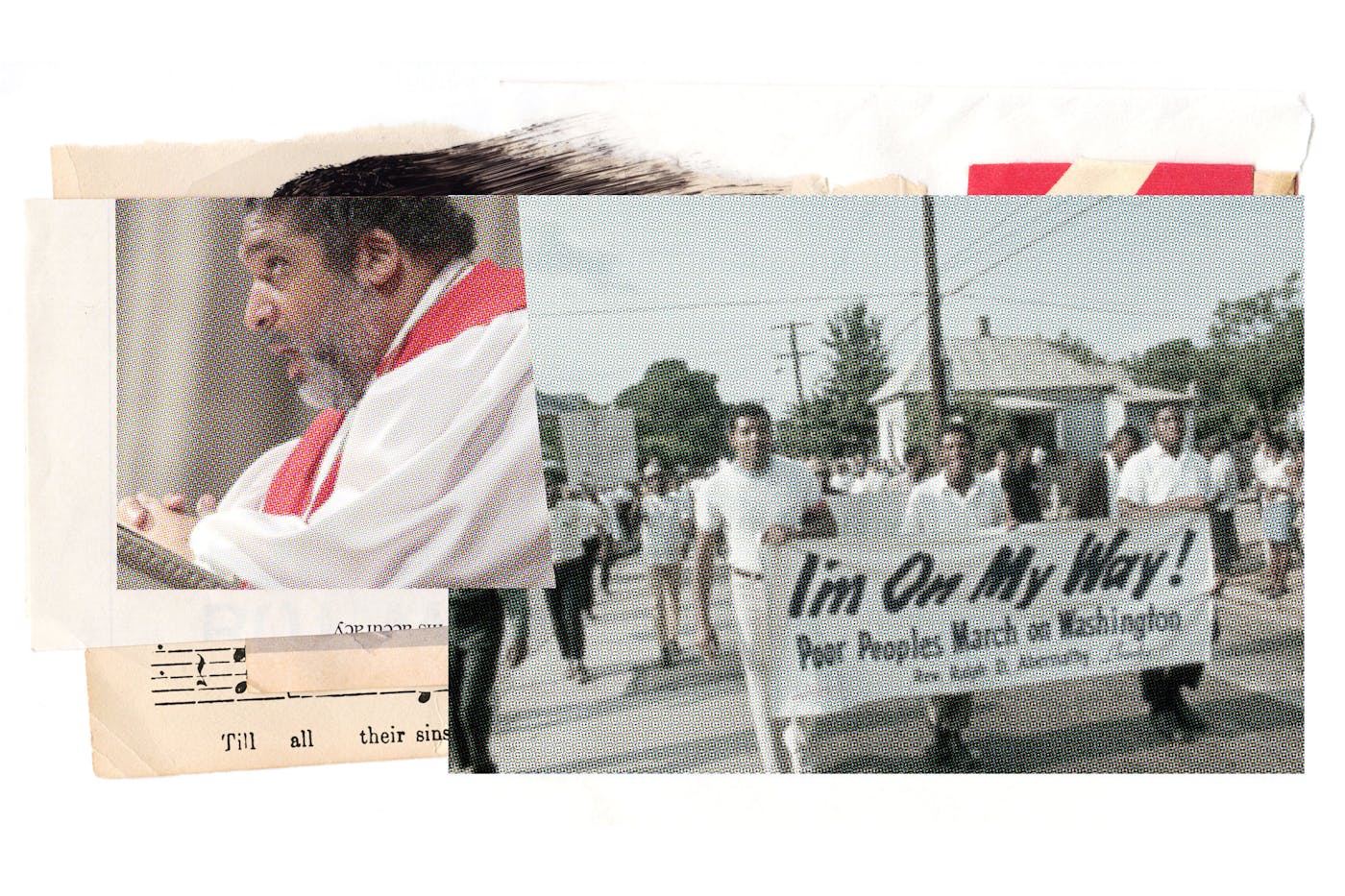

It may be useful to recall that the rise of the modern civil rights movement also took shape amid gnawing uncertainties. Long before the Montgomery bus boycott catapulted Martin Luther King Jr. into national prominence, the Black church in the South had been waging unheralded demonstrations and legal challenges against the tyranny of Jim Crow. By any conventional political calculation of rational self-interest, such efforts were doomed to failure: Not just the courts, but the entire national legislature was then under the unchallenged direction of the white supremacist South, and had been since the nation’s founding, except during the all too brief and unfulfilled interregnum of Reconstruction. But because such efforts were driven by a religious understanding of social power and the promise of communal redemption, wrested from a divine scheme of justice steeped in the Mosaic saga of liberation, these early Black church initiatives blossomed into the civil rights revolution.

No one would have banked on any such outcome when King launched his prophetic career in the mid-1950s. And importantly, none of the mainstream apostles of Cold War religious consensus, from Will Herberg to Dwight D. Eisenhower, took serious note of the Black church revival or the longer-term impact of the early civil rights protests—they were too bewitched by the idea of the grand homogenizing celestial harmonies overhead.

It bears stressing just how drastically King’s vision differed from that Cold War consensus. Just as King has been shorn of his political radicalism—his democratic socialism, his anti-imperialism—his religious particularism is too often ignored. Theologian Vincent Lloyd has noticed that, on the “inscription wall” of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. monument in Washington, the quotes chosen are rather tame. “Frequently the words justice, equality, peace, and love appear in them,” he writes. “Entirely absent is the robust religious vocabulary that King deployed: God, Christ, law, and sin. This is not only King’s religious vocabulary; it is also his critical vocabulary, the language he used to circumvent the obfuscations of segregationists and liberal reformists alike.”

That language drew, in turn, from the thought of perhaps the most influential postwar American theologian, Reinhold Niebuhr. Unlike the apostles of the generic brand of civil religion that sought to make established faiths more or less interchangeable in their social message, Niebuhr insisted on reclaiming the historically conditioned, and deeply prophetic, nature of Christian belief predicated on the quest for worldly justice and social reform. Niebuhr’s thought was a key tributary in the so-called neoorthodox turn in Protestant theology—a designation that highlighted its debt to more traditional forms of particularist worship in the West.

For King, Niebuhr’s analysis of the politics of nonviolent resistance was especially compelling. Parsing the spiritual logic of satyagraha—the successful anti-colonialist activism pioneered by Mohandas K. Gandhi in India—Niebuhr argued that such organized resistance represented a crucial form of “spiritual discipline against resentment.” Gandhi’s campaign of direct action against Britain’s imperial state powerfully demonstrated the rank injustice and discrimination at the heart of the colonial occupation of India. What’s more, Niebuhr contended, the tactical genius of satyagraha was to expose the moral hypocrisy of an oppressor’s agenda to the selfsame oppressor—and thereby stave off the descent of spiritual and political life alike into a de facto war of all against all, a prospect that was all too likely in 1932, when Niebuhr published his landmark critique of global power relations, Moral Man and Immoral Society. King’s creative adoption of Niebuhr’s analysis to the challenge of facing down white supremacy in the American South formed the moral heart of the civil rights revival.

None of this is to say, of course, that Barber or Warnock are the second coming of Martin Luther King Jr., or that today’s volatile political scene could produce a revived civil rights revolution—though of course the materials for such a mass uprising are in anything but short supply, as last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests made abundantly clear. History doesn’t work that way, in either an American or a biblical sense. But the still-recent precedent of the civil rights awakening reminds us that the resources of spiritually minded reform are broader and deeper than the gatekeepers of political consensus are apt to realize.

Unlike the bland conformity of civic religion, the prophetic calls of particularistic faiths rarely line up with the needs of political parties. This cuts both ways: The religious left, in all its diversity, will never be a reliable ally of the Democratic Party, nor will the Democratic Party always be a comfortable home for the religious left. However their fortunes are linked, the religious left, as Kaya Oakes has argued, “does not belong to one faith or one political party.” One of the chief complaints from more radical elements of the religious left is that journalists are too ready to treat any Democrat who utters God’s name as evidence that progressive believers stand ready to be a potent force in the party—a tendency that domesticates the transformative power of faith. That means the religious left faces similar dilemmas as the socialist left: discerning how far and how fast to push, how to relate high ideals to the realities of mainstream parties.

There’s no pat solution to any of this, no formula that will resolve these tensions. Which brings us back to America’s second Catholic president. No one would have mistaken Biden for a hero of the religious left, even if, so far, he’s governed in a more ambitiously progressive way than many expected—a fact for which his faith might be partly responsible. (After its passage, the National Catholic Reporter editorialized that “Biden’s American Rescue Plan is Catholic social doctrine in action.”)

Biden’s Catholicism has proved politically complicated in telling ways. His position on abortion, the issue that the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) upholds as “preeminent,” has evolved along with the Democratic Party’s to become firmly pro-choice, including no longer supporting the Hyde Amendment—a breach so alarming to the USCCB’s leadership that a special working group was formed after the election to deal with the high-profile dissent. (It was disbanded in February.) At the same time, Catholic activists working with migrants and refugees at the Mexican-American border are pushing Biden to heed Pope Francis’s call to truly welcome the stranger. That pressure will only grow if his policies continue to fail to live up to his campaign promises.

Beyond these disputes, Biden has drawn criticism from secular advocates for his public displays of religiosity. In February, Annie Laurie Gaylor, co-founder and co-president of the Freedom From Religion Foundation, told a Religion News Service reporter that her inbox was “flooded with complaints” about Biden’s inclusion of Cardinal Wilton Gregory, the Catholic archbishop of Washington, in a memorial service for those who have died from Covid-19 the day before his inauguration. Especially galling was the rendition of “Amazing Grace” during the ceremony. “For our membership, for non-religious and non-Christian individuals, it was utterly spoiled,” Gaylor said.

But the new president might offer at least one reminder to people of faith fighting for a more decent and just politics. Biden relates to the present religious moment in striking ways. The confidence he has that his Catholicism can play a role in liberal politics is of a piece with the era in which he entered adulthood—a time when Catholics engaged the modern world in fresh ways. The modern reign of the two Johns, however, didn’t last long. John F. Kennedy was killed, a prelude to other upheavals in American politics, while the Second Vatican Council, called by Pope John XXIII, quickly gave way to fierce disputes over how to interpret and implement its reforms—controversies that still afflict a church in a state of de facto schism, with charges of heresy flying and the current pope, Francis, often described in lurid terms as a deceiver undermining the Catholic Church.

When Biden was inaugurated, he brought this history with him. He stood at the center of a city under military guard, and before a nation that had just witnessed a violent insurrection. (As it happens, some of the same clerics most hostile to Francis also lent their imprimatur to Trump’s “Stop the Steal” campaign.) Perhaps that should give pause to those on the religious left inclined to dismiss Biden’s calls for healing—or at least prompt them to discern the deeper truth such calls point toward. The radical Dominican priest Herbert McCabe, in his essay “Christ and Politics,” argued that the Gospel, unlike socialism, “is not a programme for political action: not because it is too vague and general or too private, but because it is also a critique of action itself, a reminder that we must think on the end.” He then elaborated:

The Christian socialist, as I see her, is more complex, more ironic, than her non-Christian colleagues, because her eye is also on the ultimate future, on the future that is attained by weakness, through and beyond the struggle to win in this immediate fight. But even short of the eschaton, the Christian is also more vividly aware not only of the need to avoid injustice in the fight for justice (as any rational non-Christian socialist would, of course, be) but also of the need always to crown victory not with triumphalism but with forgiveness and mercy, for only in this way can the victory won in this fight remain related to the kingdom of God.

Without that opening on to a future (and, as yet, mysterious) destiny, what begins as a local victory for justice becomes, in its turn, yet another form of domination, another occasion for challenge and struggle….

It seems fair to assume that when Biden invokes unity or dialogue, it is more a plea to return to normalcy than a posture toward the eschaton. These appeals, amid Republican intransigence, can feel forced or, worse, terribly naïve. At times, Biden appears to actually believe that he can overcome the divisions afflicting the country through force of will, and perhaps a little backslapping charm. But that doesn’t mean he can’t imperfectly remind us of a deeper reality: Politics always takes place in the shadow of death, among people who even during righteous campaigns fail to honor the dignity of their neighbors. The task of the religious left can’t be found in demographics or the polls, or in the divine sanction it can offer for this or that policy. Instead, it is found in offering witness to the possibility of a beloved community, one that sees eternity looming beyond the next election.