I studied to be a painter in college and had what I now know is a pretty common experience. My fellow students and I produced dumpster loads of bad art, debated theory that was nearly 20 years out of date, and never really spoke about how we planned to make a living once this idyll of calm had passed and the bills started coming due. When I moved to New York City almost a decade ago, I found a job cooking, as I figured I would. I had only ever held service jobs, going on the assumption that waged labor was completely separate from the individualistic and lonely practice of painting. But soon I happened into work installing art at a museum. I quickly found this was much better than a job at a restaurant. For one thing, I actually had something in common with my coworkers, because they were almost all working artists: sculptors, writers, musicians, painters, and designers. All day we installed art, worked with artists, trucked crates around the city, and did light construction. We were mostly freelance or temporary employees, but there was plenty of work.

To my surprise, working in the art world seemed, at least in small part, to facilitate the work of artists. The schedules accommodated workers who were frequently jetting off to monthlong residencies, going to school, or taking time to work in their studios. The job also functioned like a second art education and a social scene, and one that paid. Many days, we would look at and talk about art, often for lengthy and intimate periods. Colleagues got together to launch small galleries and project spaces. It turns out that even fine art, one of the most solitary areas of creative production, wasn’t isolated; it was a community effort. The network of jobs at galleries, auction houses, and trucking companies employing thousands of people was an unseen circulatory system of the art world that not only pumped vital income to artists but also transmitted the more immaterial and intangible hormones of culture. It is impossible to draw a line between the art world’s institutions, the workers who keep them running, and individual pieces of artwork. It’s an inextricable relation: Without the high-end art world of New York, centered around a few superstars and mega-galleries, I doubt there would be many other artists living in New York, and vice versa.

While this system produces culture, no one is paid enough, and the rent climbs ever upward. I once worked an art fair with a kindly but grizzled art handler who told me that he’d been making the same rate per hour for the last 15 years. The art world runs on freelance workers, and few have employer-provided health care. On most days, the system, overpowered on oligarchic-level wealth, feels as if it is on the brink of spinning apart. This is not exceptional: Art workers are but a slice of the art world, which itself is a portion of the wider culture industry that is verging on collapse. Many creative people today are swimming barely above the poverty line. The walls are caving in everywhere: Book publishing is contracting and consolidating; the music industry is taking huge blows in the transition to streaming; and journalism, as The Observer reported recently, shed 260,000 jobs between 2000 and 2018 (far outstripping the losses in coal mining, it adds).

Contemporary critics often attribute this downward spiral to the rise of exploitative tech platforms: Musicians can release an album on Bandcamp, but they’re still broke; documentarians can distribute their film online, but people can easily watch for free; journalists can blog until their fingers fall off, and never see a cent. Other critics fault the creative people themselves for embracing an “Andy Warhol cynicism” that emptied art of meaning. The proposed solutions, it follows, lie narrowly in tweaking the way we buy and sell art: Maybe copyright reform would restore a bit of the revenue from royalties, or maybe artists should act more like entrepreneurs, hustling until they find their way into a profitable niche. Some of these measures might help individual writers or performers. Less clear is how they would reinvigorate the larger ecosystem that encompasses the editors and staff writers at newspapers and magazines, the scenic painters on television sets, the assistants in an artist’s studio.

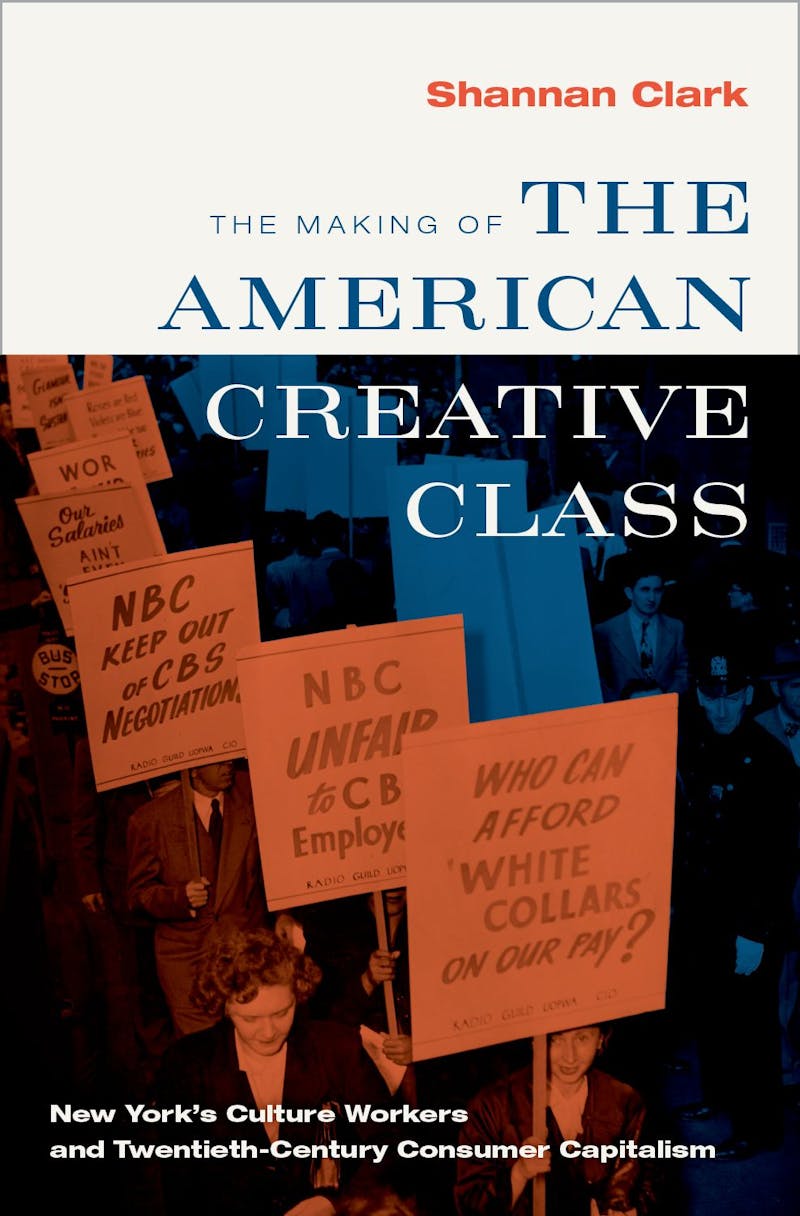

Shannan Clark’s new book, The Making of the American Creative Class: New York’s Culture Workers and Twentieth-Century Consumer Capitalism, offers a much more ambitious vision of a thriving creative sphere—one that existed in fact for several decades in the middle of the twentieth century. The story of workers in broadcasting, publishing, advertising, and industrial design (including clerical and supporting staff), it shows how the creative class was built, not by entrepreneurial individuals but by myriad groups attempting to weather the lumbering forces of history. These groups identified their problems not as problems of art-making but as the problems of workers. Uniting around explicitly political aims, they recognized not only how extensively they relied upon one another, but also how closely their fates were linked with the fortunes of America’s broader middle class.

The creative class as we know it emerged as a by-product of industrialization and the introduction of a consumer economy. The Making of the American Creative Class begins just before the mass industrialization of America in the 1880s. At that moment, much of the middle class was composed of store owners and professionals like doctors and lawyers. Industrialization created the need for not only salaried managers, but a smattering of office workers, from clerks to accountants, designers, engineers, in-house lawyers, typists, and secretaries. White-collar work exploded into existence between 1880 and 1949, far surpassing the growth in blue-collar work. Professional jobs grew by 481 percent, the number of managers by 568 percent, and clerical employment increased by 1,767 percent.

In the growing mass consumer economy, manufacturers had to find a way to make their goods desirable to the public. With the birth of advertising, white-collar work became creative. Not only did advertising require designers and marketers, but it also funded a rapid growth of news media, which became the primary conduit for manufacturers to reach their intended audience. From 1880 to 1929, advertising expenditures grew from 44 percent of revenue to almost 75 percent, bringing about “a revolution in newspaper and magazine publishing.” Newspapers, the major recipient of the advertising dollars, used the money to expand their coverage and ambitions to new levels. Long-form and investigative journalism blossomed. New printing technologies enabled mass media and thus mass employment for an entire group of writers, photographers, printers, designers, editors, and artists. New York City became a beacon for creative people, Clark writes, not only because of its “flourishing bohemia” but also because of “its opportunities for remunerative employment.” This in turn caused more outlets to set up shop in New York. It was a dense, interconnected web of relations all underwritten by a booming consumer economy. Culture begat more culture.

But it didn’t last. The financial crash of 1929 and the onset of the Depression caused producers to scrap their advertising budgets, sweeping away the foundations of this arrangement. White-collar professionals and creative workers across the country were sacked by the thousands. Workers across industries woke up to the fact that they couldn’t rely on the benevolence and largesse of owners of private capital to ensure their existence. If they wanted a future, they would need to join together.

The 1930s saw a major uptick in organizing in the creative industries, with efforts spurred by a Popular Front coalition of progressives, social democrats, and communists. In this period, the American Newspaper Guild; the Federation of Architects, Engineers, Chemists, and Technicians; the United American Artists; the Book and Magazine Guild; the American Advertising Guild; and numerous radio broadcasting unions saw their numbers swell, as did the enormous United Office and Professional Workers of America (UOPWA). Some of these groups, like the Ad Guild, failed to gain traction. But some found major success, as did the Newspaper Guild, which by 1941 had a nationwide membership of 19,000 and had won recognition at almost all the major newspapers in New York City, as well as at the magazines Time and Newsweek.

Some unions ran their own radio stations and publications, and explored business models that weren’t directly dependent on industrialists. Other journalists, similarly aware of the fickle nature of private capital, experimented with cooperative ownership and with subscriber- and labor-funded publications like PM, Friday, and In Fact. Unionized cultural workers could expect a middle-class salary that, for a while, kept up with the storied, rising wages of industrial workers. An average Newspaper Guild member in 1944 made nearly $50 a week, at a time when rent in New York City was around $50 a month, making it possible to support a family on a single income. Higher pay and shorter hours even meant that some jobs served, accidentally, as fellowships for the early years of an artist’s career. (Think of the many mid-century artists who worked doing commercial design, like Andy Warhol and Willem de Kooning.)

The culture workers in Clark’s book also looked to improve conditions beyond their own workplaces, throwing their support behind unemployment benefits, overtime pay, and Social Security. They wanted to use their collective power to bring about a more resilient economy, based on some amount of public ownership of industry, and to further the social-democratic, egalitarian promise of the New Deal. During the war, the Newspaper Guild, in its weekly radio show, not only espoused what Clark calls the “prevalent Popular Front discourse of antiracism and social consumerism” but connected listeners to block-level CIO Community Councils. These local groups fought against wartime inflation and backed, among other things, a system of free childcare centers for working mothers in New York City.

The same programs that hauled the United States out of the Great Depression and launched it into the prosperity of the postwar boom supported cultural workers. When the Works Progress Administration confronted mass unemployment with a huge program of job creation, jobs in the cultural industries were included. The Federal Art Project ran programs like the incredible Index of American Design, in which hundreds of artists were paid to produce watercolor illustrations for an archival catalog of thousands of uniquely American objects. The FAP also funded pathbreaking schools like the Design Laboratory, which helped define American Modernism, and financed revered institutions like the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. The Farm Security Administration, another New Deal program, hired a host of now-famous photographers, including Russell Lee, Dorothea Lange, and Walker Evans, to roam the country and document rural life and poverty in America, creating an unmatched body of work that would not have existed without public funding.

Reasserting the radical history of this country’s culture industries, The Making of the American Creative Class shows the far-reaching influence of labor law and politics on culture: Artists in the middle of the twentieth century flourished not because the economy was inherently favorable to them, but as a result of powerful economic winds and the groups that joined in an attempt to harness them. Together, creative class groups wielded the crowbar of politics in an attempt to pry some autonomy out of consumer capitalism.

If these standards of living were sharply eroded over the last 50 years, it is partly because the institutions that once upheld them had also fallen away. The McCarthyist anti-communist fervor of the early Cold War decimated creative class unions themselves, which tended to be much further left than the rest of the labor movement. The UOPWA was cast out of the American Federation of Labor, and the purge of pro-communist members neutered the revolutionary potential of groups like the Newspaper Guild. The labor movement, which at the top level was thoroughly white, male, industrial, and conservative, was happy to watch the creative left flank die, leaving its power unchallenged.

In the late 1960s, the country began to deindustrialize, which slowly eroded the bargaining power of the labor movement as a whole. It also caused an economic crisis for creative professions, as declining advertising revenue once again led their finances to crater. In the 1970s, many stalwart newspapers and magazines, like Life, closed their doors, and journalists faced mass layoffs. At that same moment, wages stagnated for all workers (a trend that continues today). Without the funds or vision to invest in organizing, white-collar unionism dimmed until it was barely perceptible. As the radicalism of the mid-century faded with the Reagan and Clinton eras, public support for social welfare programs declined, income inequality skyrocketed, and asset prices (not to mention rent and the cost of education) exploded to feed the needs of the insurgent financial sector. In an age of intense individualism, creative workers were largely left to fend for themselves.

Today, as in the 1930s and ’70s, we have to reckon with the precariousness of creative work in industries too dependent on private patronage and increasingly consolidated ownership. When culture depends on the exhaust of the consumer economy—that is, advertising—what happens when it peters out or is monopolized by tech corporations? The speed with which private equity can suck the life out of a newspaper, and the way that Facebook can unilaterally cause a pivot to video, are just two recent examples of how brittle and monopolized the production of culture has become.

With its explicitly political framing, Clark’s history makes clear that we can’t separate the fates of the creative class from others. When you really look hard, it is impossible to clearly delineate where the creative class ends and any other class begins. Think about the accountant at a museum. Do they qualify? Without them, the museum wouldn’t function. But what about the museum’s banker? The reality is that art institutions, just like record labels and publishing houses, require a sprawling mass of people to run. Not to mention that the creative classes need an audience: people with enough income to buy a range of books and paintings, and enough free time to go to concerts and museums.

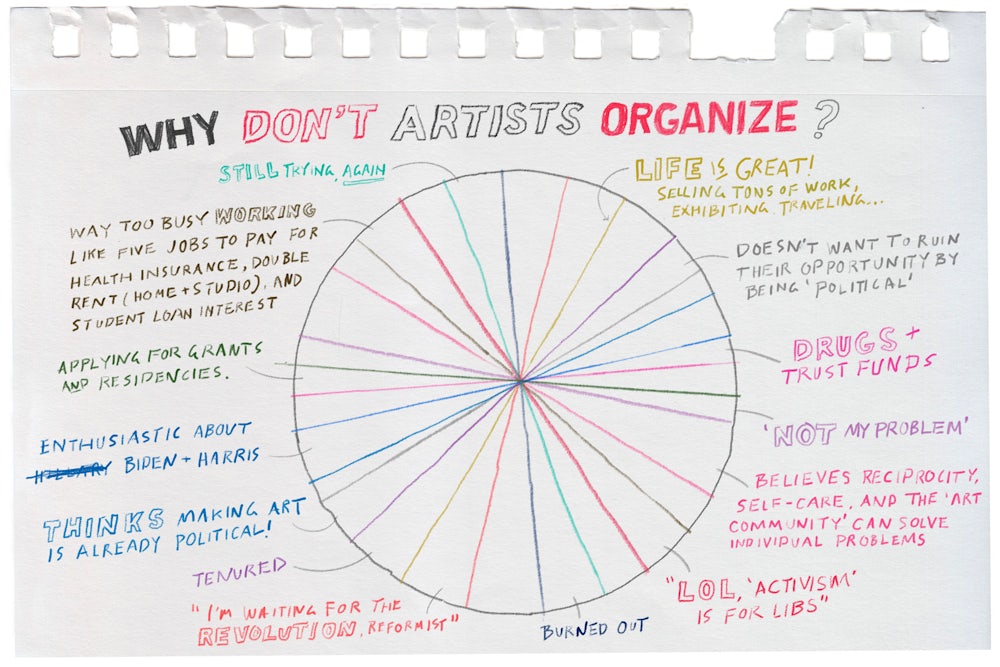

The problems that affect creative workers and restrict their autonomy are more or less universal across society. Consider someone who desires to be an elementary school teacher, but finds the pay is so low they must either take additional jobs or go into another field entirely. Or a geologist who’d prefer to continue their work studying global warming’s effect on permafrost but can only find jobs at fossil fuel companies. Or someone who wakes up at 2:15 a.m. to commute three hours because they can’t afford to live in a neighborhood closer to their office. Our current economic system leaves the majority of people, including creative workers, vulnerable and powerless. As many authors writing about the creative class mention, something as simple as cheap rent facilitates culture. Ask any art worker what invisible hand drags them out of their studio and pushes them into another job: It’s rent, health care, and student loan payments.

A straightforward initiative to save our creative class and the middle class might be to reinvigorate the mid-century project: Empower workers while ensuring they have the lowest cost, best-quality health care, childcare, education, food, and housing. To some small extent, the creative class has recently begun to reenact this history. In many newsrooms, including at the once staunchly anti-union Los Angeles Times, journalists have organized in order to gain a degree of control over their lives. As have many art workers across the nation, including those at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the New Museum, the Frye Art Museum, and—as part of a group of workers at my first job in the art world—me. But unionism is not nearly enough. The creative class en masse will need to get behind political movements that aim to provide low-cost housing, curtail the financial sector, and reinvest in public schools and municipal infrastructure.

In school, we never talked about who works in the museums, who paints the walls after an exhibition, who sells the art, or who owns the gallery and why. We saw culture through the keyhole of individualism, which made it almost impossible to connect the conditions for working people in general with our bleak economic prospects as painters. No wonder the solutions we came up with were always unsatisfying and self-helpy: Wake up early! Apply for those grants! Sell yourself! For me, these tactics dissolved after probably the tenth time installing a show by a living artist, and the artist didn’t even show up to hang. It became impossible to think of an art show, or even an artist’s career for that matter, as solely attributable to the artist. But rather than being some kind of saddening encounter with dismal Oz behind the curtain, it clarified the art world: a tenuous group project I was a part of, embedded in the political problems of the day, swaying with the larger forces of history.