In early January, the Center for American Progress (CAP) released a report, co-authored by former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, that outlined policy solutions to the weak economic and wage growth currently in the U.S. Given CAP’s well-known ties to the Clintons—Neera Tanden, the president of CAP, is an adviser for Hillary Clinton’s campaign—the policy recommendations are widely considered to be a preview of Clinton’s domestic agenda.

“There is a need for policy to ensure that growth is broadly shared with employees, not just employers and the owners of firms,” Summers writes, citing income inequality as a key challenge facing the country. The report suggests a number of solutions, including increased infrastructure spending, universal pre-K, raising the minimum wage, and expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). Some of these solutions are targeted at middle class households, while others are designed to improve the lives of low-income Americans.

In a recent essay at National Review, Ramesh Ponnuru and Yuval Levin sum up the report thus:

The bad news for conservatives is that, although the progressive agenda outlined in the report is not well suited to the circumstances and challenges of contemporary American life, it is designed for political appeal and may well have some. The good news is that, by applying their principles to the core problems Americans now face, conservatives could readily outline an agenda that would both do more to strengthen economic growth and opportunity in America and be more attractive to the public.

Their counter-proposal, one that they believe "satisfies both the public’s desire for smaller government and its interest in a higher middle-class standard of living," begins with tax reform—specifically, expanding the tax credit for children. That idea is supported by just one Republican presidential candidate— Senator Marco Rubio—and has been widely criticized by the rest of the party. For their part, the Democrats want to support parents through the tax code; Obama has proposed expanding a tax credit for child care for instance. Ponnuru and Levin also support expanding the EITC and giving workers a share in company earnings, as Democrats do, and want to "take on the higher-education cartel" by promoting new ways for students to finance college and allowing states to experiment with new accreditation systems.

That's Ponnuru and Levin's article in a nutshell: a litany of Reformocon ideas that the GOP "could" adopt, but many of which will be ignored, if not outright opposed, by a party that remains straightjacketed by extreme conservatism. The authors themselves seem to recognize this:

For all the constraints under which the report suggests the Democrats are laboring, this agenda could nonetheless trump a particular kind of conservative platform. The last two Republican presidential campaigns were fairly light on policy ideas, and the overall message they conveyed to voters was that all would be well if the federal government restrained spending, liberated entrepreneurs from regulation, and cut taxes, especially on businesses. (In 2012, repealing Obamacare and replacing it with something or other was added to the list.)

The 2016 Democrat agenda may not have one Big Idea, a silver bullet for the nation's economic and social woes, but their most recent Big Idea—as the above passage explicitly acknowledges—became law: the Affordable Care Act. Meanwhile, three years removed from President Barack Obama's reelection, the Republican Party's one Big Idea remains the same: to repeal the Affordable Care Act. And that alone overshadows all of the ideas on the right—smart or dumb, reformist or conservative, realistic or pie-in-the-sky—for addressing income inequality and helping the middle class. Merely saving Obamacare will do more for those Americans than anything and everything you'll find in the Republican Party platform.

When Democrats lost in a Republican wave in last November's midterms, liberals let off a primal scream about the party’s agenda. “The Democrats’ failure isn’t just the result of Republican negativity,” Harold Myerson wrote at the American Prospect. “It’s also intellectual and ideological. What, besides raising the minimum wage, do the Democrats propose to do about the shift in income from wages to profits, from labor to capital, from the 99 percent to the 1 percent?”

Myerson is right that the Democrats, including liberal heartthrob Elizabeth Warren, don't have all the answers. But the CAP report shows that the left is not bereft of ideas to address rising income inequality, which include raising the minimum wage, guaranteeing paid sick leave and vacation time, and expanding the EITC. The left-leaning Economic Policy Institute projects that raising the minimum wage to $12 per hour by 2020, which Senator Patty Murray and Representative Bobby Scott proposed last week (and Obama supports), would boost the wages of 31 million Americans, more than a quarter of the workforce. President Barack Obama has included many of those policies in his “middle class economics” agenda, even though some are more likely to help the poor. But the CAP report does include distinctly middle-class proposals such as universal pre-k, principal reduction for underwater homeowners, and income-based repayment to make it easier for college graduates to pay back their student loans.

To Ponnuru and Levin, these ideas comprise a stale agenda, one that recycles old ideas for new problems. Clintonian economics are ill-suited for twenty-first-century America, they argue:

[B]y describing Clintonism as the force behind the last great recovery, it stacks the deck in favor of recycling a Clintonian economic policy into a prescription for what ails us now. This is, to put it mildly, an implausible strategy, as today’s economy is hardly similar to the one Bill Clinton inherited in the 1990s. The report acknowledges that differences exist yet still argues for essentially the same ideas, and the assessment of our contemporary predicament that it employs to link the two is unpersuasive.

To some extent, this is true. The CAP report indeed puts forth many ideas that have long been popular in the Democratic Party, and that's because the left hasn’t undergone a substantial ideological shift over the past 25 years. Meanwhile, since 2012, the Republican Party has undergone a shift to the right. On immigration, many Republican candidates want to roll back Obama's executive actions and even oppose the DREAM Act, which would allow undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children to live here legally. The GOP field, particularly Senator Rand Paul, is hostile to antipoverty spending, under the belief that it fosters dependence and weakened the economic recovery. And most candidates are coalescing around a flat tax, an idea promoted by the Heritage Institute’s Stephen Moore.

Ponnuru himself denounced the flat tax as politically unwise. “[Moore] believes that flat taxers should popularize the idea of ending the charitable deduction by calling it a giveaway for the rich,” he wrote at the end of April. “I am less convinced that starting a fight with nearly every charity in the country would make it easier for Republicans to win a presidential race.”

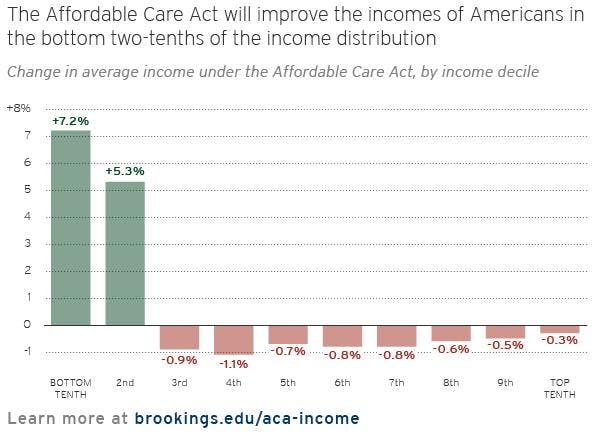

While most GOP candidates are paying lip service to income inequality, there is almost no substance behind their rhetoric. Nowhere is this more notable than the Republican Party’s focus on repealing Obamacare. The Brookings Institute found that the health care law’s benefits accrue entirely to the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution:

Obamacare is still in its early stages; health care experts will be studying its effects for years to come. But so far, none of the GOP's fears about a "death spiral" or skyrocketing premiums have come true. Judged on other metrics, like the cost of subsidies and number of people insured, Obamacare has surpassed the expectations of health care experts.

The right's obsession with ruining Obamacare is worth remembering every time a Republican pays lip service to income inequality. It's a victory, of sorts, for the left that Republicans even raise the problem of inequality—as opposed to denying its importance altogether—but that's substantively meaningless until the Republican presidential candidates deliver policies to reduce it. Democrats may not have all of the solutions that the Prospect's Myerson longed for after the midterms, but they do have a bona fide agenda chock full of economic and social policies that would help millions of Americans if enacted. It's the Republicans, contra Ponnuru and Levin, whose stale ideas are unfit for the challenges of our time.