President Barack Obama's 2012 re-election shocked many Republicans—most famously, Karl Rove—and prompted a reckoning within in the party. Erick Erickson, the conservative blogger and radio host, wrote, "The Romney campaign to the hispanic community was atrocious and, frankly, the fastest growing demographic in America isn’t going to vote for a party that sounds like that party hates brown people." Sean Hannity and Rupert Murdoch both came out in favor of immigration reform. “Look at the last election,” Senator John McCain said on ABC. “We are losing dramatically the Hispanic vote, which we think should be ours for a variety of reasons, and we’ve got to understand that.”

The Republican National Committee, meanwhile, commissioned a post-election autopsy titled the "Growth & Opportunity Project." "We are not a policy committee,” the report read, “but among the steps Republicans take in the Hispanic community and beyond, must be to embrace and champion comprehensive immigration reform. If we do not, our Party's appeal will continue to shrink to its core constituencies only."

All of that post-election hand-wriging was for naught. In the 25 months since the RNC report, the Republican Party has indeed changed in significant ways—but not in the direction that its leaders and strategists had urged. Instead of passing immigration reform and adopting policies that appeal to a broad swath of constituencies, the party has become more hostile to undocumented immigrants and doubled down on unpopular policies that disproportionately benefit the rich. Rather than moderate its positions, the GOP has moved even further right, resulting in a 2016 presidential field that is far more conservative than three years ago.

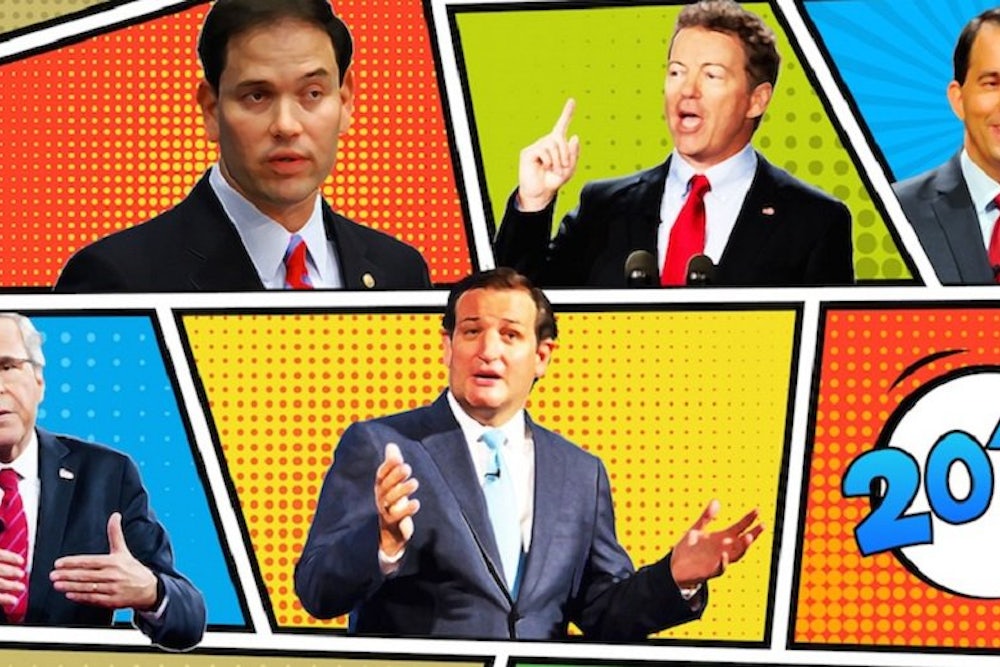

No candidate has embodied the GOP’s attempt to adopt a more appealing immigration policy than Florida Senator Marco Rubio, who announced his presidential bid on April 13. After the 2012 election, Rubio, a young Cuban-American from Miami, was immediately considered a favorite for the 2016 nomination. But his role in crafting the 2013 Senate immigration bill, which included a pathway to citizenship, cost him support among the conservative base. His support in Republican primary polls, which was above 30 percent after Obama’s re-election, fell below 10 percent and hasn’t recovered.

Rubio has since reversed his position on immigration reform. He now supports a piecemeal solution that focuses on border security and allows undocumented immigrants to apply for temporary non-immigrant status after undergoing a background test, learning English, and paying a fee. To be fair, this is better than Mitt Romney’s “self-deportation” position. But it is a step backwards from his support for the original Senate immigration bill.

Even more revealing is his shift on Obama’s 2012 executive action that allowed young undocumented immigrants to live and work in the United States without fear of deportation. In doing so, Obama effectively implemented the DREAM Act—a bill that Rubio himself intended to introduce in 2012. “I cannot imagine a scenario where a future president is going to take away the status they’re going to get,” Rubio said about the executive action in 2013. In February, Rubio tried to do just that by voting for a funding bill that would have defunded Obama’s executive action, opening up thousands of DREAMers to the threat of deportation.

These aren’t mutually exclusive positions. Rubio can support the policy implications of Obama’s executive action but not the action itself. Yet, his rhetoric has become hostile towards DREAMers as well. When immigration advocates interrupted a Rubio speech in 2012, he said, “These young people are very brave to be here today. They raise a very legitimate issue.… I ask that you let them stay. I don’t stand for what they claim I stand for.” But when advocates interrupted a speech last August, he said, “They’re harming their own cause because you don’t have a right to illegally immigrate into the United States.”

Other Republican candidates support policies that are even more unpopular with Hispanics. Senator Ted Cruz, for instance, was one of the conservative leaders who pressured the House to block the Senate immigration bill. Senator Rand Paul, in a 2013 interview with the conservative website WorldNetDaily, said he would have voted against the DREAM Act “because the DREAM Act didn’t fix the border." Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker admitted that he had changed his position on a pathway to citizenship, after saying in 2013 that it “makes sense.” Appearing on “Fox News Sunday,” Walker said, “My view has changed. I’m flat out saying it.”

Former Florida Governor Jeb Bush is the only top-tier candidate whose position on immigration is more Hispanic-friendly than “self-deportation.” Bush opposes Obama’s executive actions, but supports the DREAM Act and has suggested that he’d support a pathway to citizenship—a position that, tellingly, is considered one of his biggest liabilities in the GOP primary.

In 2012, Mitt Romney wanted to extend the Bush tax cuts, cut taxes across the board by an additional 20 percent, and offset the lost revenue by closing unspecified tax breaks. The plan was just about mathematically impossible. Herman Cain, another 2012 Republican presidential candidate, proposed a 9-9-9 tax plan—a 9 percent income tax, 9 percent national sales tax and 9 percent corporate tax. “The plan has been designed to be revenue neutral initially, and then revenues would grow in line with the economy,” Cain wrote in a Wall Street Journal op-ed.

Not every candidate determined that their tax plan had to be deficit neutral. The Center for a Responsible Federal Budget estimated that Newt Gingrich and Rick Santorum’s tax plans would reduce federal revenues over a decade by $7.1 trillion and $6 trillion, respectively. But Santorum, Gingrich, and the rest of the 2012 field weren’t considering how their tax plans would play in the general election. They instead were focused solely on winning the primary. Romney, on the other hand, had to craft a tax plan that was both amenable to the primary electorate and to general election voters—and that meant saying his tax plan was deficit neutral. After Republicans spent the first term fear mongering over the deficit, Romney couldn’t propose a massive tax cut without appearing hypocritical.

While the GOP has continued to fear monger over the deficit, the Republican candidates for the 2016 election do not share Romney’s hesitancy to propose a tax cut. Rubio, for instance, has proposed a tax plan that would cut taxes by $4 trillion over the next decade. Paul promised the “largest tax cut in American history. Cruz will likely try to top them both. Rubio, Cruz, and Paul are not Hail Mary candidates like Santorum, Gingrich, and Cain were in 2012. They’re legitimate contenders.

Instead of updating their policy platform after 2012, the Republican Party has opted to adjust its rhetoric. Gone are comments about the “47 percent” and “takers versus makers,” replaced with critiques about rising income inequality. But if you look beneath the surface of these remarks, nothing has really changed. The GOP’s 2016 field has the same apathy for the poor that the 2012 field demonstrated—the new group is just better at hiding it.

Take Scott Walker, who shot up in GOP polls after a widely praised speech in Iowa in January. “In all the years I was in school, doesn’t matter whether it was in Plainfield or Delavan, here in Iowa or Wisconsin, there was never a time when I heard one of my classmates say to me, ‘Hey Scott, hey Scott, some day when I grow up I want to become dependent on the government,’ right?” he said. That sounds innocuous, but this is the same Republican critique of government programs: They become a “hammock” for the poor.

More than almost any other Republican candidate, Rand Paul has argued that government programs cause dependency. “Americans are unwilling to work for $8 an hour and pick crops because they can sit at home and watch soap operas for government pay for 10 bucks an hour,” he told WorldNetDaily in 2013. “The problem is, we have a very generous safety net, maybe overly generous. What I say is if they look like you or look like me and they hop out of their truck, they shouldn’t be on disability.” Paul was one of the loudest opponents against extending federal unemployment benefits, which he argued do a “disservice” to the poor. And the budgets he released in 2012, 2013, and 2014 all necessitated massive cuts to programs for low-income Americans.

Rubio may have the most credible antipoverty position of any candidate. His plan would increase benefits for childless, working adults. But his proposal doesn't have a funding source. He says benefits for childless working adults will increase, benefits for everyone else will stay the same and the plan is somehow magically deficit-neutral. That math doesn't work.

These plans don't represent a shift to the right on issues of income inequality and antipoverty spending. Instead, they are similar to what Romney and other GOP candidates offered in 2012 (namely, big spending cuts). The only difference is that the top candidates for 2016 have disguised these policies with less divisive rhetoric.

The 2016 campaign is only a few weeks old, and most candidates haven’t even outlined their policy platforms. But it’s already clear that the Republican candidates are positioning themselves to the right of Mitt Romney. Eventually, Cruz and other hardline conservatives start attacking Bush and Rubio, as relatively centrist Republicans, for being too nice to undocumented immigrants and the poor. If the field is already this conservative, imagine where they’ll be a year from now.

This isn't necessarily a huge advantage for former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. I endorse Jonathan Chait’s theory that the electorate has largely transformed into two partisan blocs that vote for the same party in each election. As the Democratic bloc increases, that will give Clinton and future Democrats a built-in advantage in presidential elections.

But the Republican Party’s move to the right still could have a meaningful impact on 2016. First, the lack of a Democratic challenger means Clinton does not have to move significantly to the left to win the primary. That puts her in a better position to promote center-left policies that appeal to the few remaining swing voters. Second, the Republican Party’s position on immigration only hardens Hispanic beliefs that the GOP doesn’t care about them. Third, it’s hard to imagine that the Republican field can beat up on each other and on Clinton for the next 19 months without insulting key voters. Whether those insults come from Ted Cruz about Hispanics or Rand Paul about the poor, I don’t know.

If the GOP is truly determined to shed its image as hostile to undocumented immigrants and the poor, its candidates must go beyond voicing concern about those groups. They must propose realistic policies to make these people's lives better. The 2012 election should have been a wake up call in this respect. But based on what we've heard from the party's new presidential crop, it clearly wasn't.