In February 2013, President Barack Obama proposed raising the minimum wage from $7.25 per hour to $9 per hour. Former Senator Tom Harkin and former Representative George Miller deemed that insufficient and counter-proposed a raise to $10.10 per hour. By November that year, the president agreed with them.

Now, congressional Democrats are trying to push the minimum wage even higher: On Thursday, Senator Patty Murray and Representative Bobby Scott introduced the “Raise the Wage” Act, which would raise the minimum wage to $12 per hour by 2020.1 Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, and Labor Secretary Thomas Perez joined Murray and Scott at a press conference Thursday afternoon. (Perez announced that Obama "enthusiastically supports" the bill.) It’s an indication that the plan has wide support in the Democratic Party.

But is it a good idea? Probably, even though it carries some economic risks. Here’s why.

Raising the minimum wage to $12 per hour—a 39.6 percent increase—may seem large, but it’s not unprecedented. Congress last raised the minimum wage in 2007, hiking it from $5.15 to $7.25—a 41 percent increase that took effect over four years.

If Murray-Scott passes, the $12 per hour minimum wage wouldn’t kick in until 2020, five years from now. In fact, according to a new study from the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, the annual percentage increase in the minimum wage would peak at 12.5 percent in the second year. (When the minimum wage rose from 2007 to 2008, it increased by 13.6 percent.) So while Murray-Scott’s $4.75 increase is larger than any previous minimum wage hike in nominal terms, it’s nothing unprecedented in relative terms.

Conservatives will likely argue that those previous minimum wage hikes cost the country jobs, so policymakers should expect the same from Murray-Scott. But as Jared Bernstein—the former chief economist to Vice President Joe Biden—explains at the Washington Post, the academic evidence on minimum wage hikes shows at most very modest negative effects on employment.

The biggest concern with Murray-Scott, though, is that it uses a one-size-fits-all policy to adjust the minimum wage each year. Unlike most minimum wage proposals, Murray and Scott don't propose adjusting wages each year to keep up with inflation. Instead, they would increase it each year to keep up with median wages, the midpoint of the wage distribution. If median wages rose 1 percent, then the minimum wage would rise 1 percent. As economist Arindrajit Dube has explained, this is a good idea—but it should be done at the state level, not nationally.

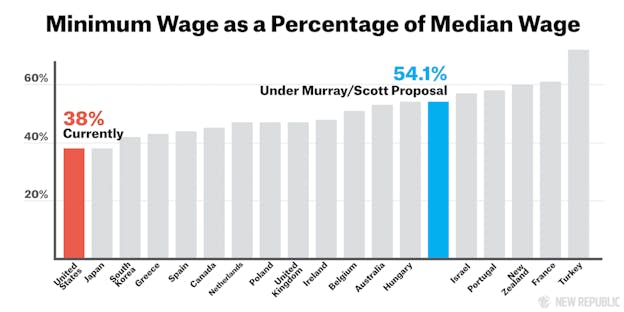

Workers don’t actually care that much about their wage level. They care about what they can buy at that wage level—and the median income of an area is a good proxy for its cost-of-living. The U.S. minimum wage, relative to its median income, is currently one of the lowest in the developed world. The majority of countries cluster around the minimum wage being equal to 50 percent of the median wage. According to EPI’s new study, Murray-Scott would raise the minimum wage so that it equals 54.1 percent of the U.S. median wage in 2020. That would put America slightly above most nations but below Turkey, France, and a few other countries.

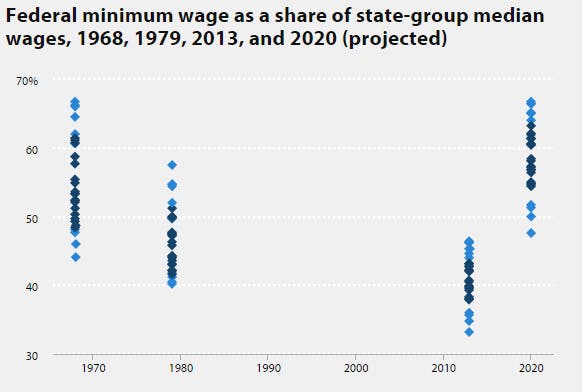

While Murray and Scott are correct to focus on increasing the minimum wage relative to the median, they fail to account for regional price differences. In states with lower median wages like Mississippi, Arkansas and West Virginia, a $12 per hour minimum wage will lead to a minimum wage to median wage ratio of around 60-70 percent. That’s above almost any other advanced economy.2

EPI’s economists argue that this isn’t that concerning because the minimum wage to median wage ratio was near 70 percent in low-wage states in 1968. “We think there’s every reason to believe, since there didn’t seem to be any significant negative effects back in the ’60s, we wouldn’t anticipate them now,” David Cooper, an economic analyst at EPI and one of the authors of the study, said in an interview.

That’s fair. But I still am concerned about the timing of Murray-Scott. In low-wage Southern states, the minimum wage would become a much higher percentage of the median wage in a relatively short timespan. Consider Alabama, where the median wage was $14.83 in 2014. The minimum wage to median wage ratio was 48.9 percent last year. According to EPI, Alabama’s ratio under Murray-Scott would rise to around 65.1 percent in 2020. There’s no academic evidence of such a rapid increase in the minimum wage to median wage ratio. Low-wage employers in those states could have a significant trouble adjusting to the law.

“I don’t think we know exactly what would happen because this is a bolder proposal than we’ve seen in recent times,” Cooper said. “But from what we do know, we don’t think it would be too onerous even in lower-wage states.”

Over a longer timeframe, Murray-Scott also could hurt minimum wage workers in low-wage states. For instance, imagine if the median wage grows at half the pace in Alabama as it does nationally (1 percent vs. 2 percent, for example). Alabama’s minimum wage will increase by 2 percent, not 1 percent, since the minimum wage rises based on national median wage growth. While the national minimum wage to median wage ratio will stay constant, Alabama’s ratio will rise. Remember, Alabama and other low-wage states already have high minimum wage to median wage ratio. If this happens over a long enough period, the negative employment effects could become significant.

To be clear, there’s evidence that the opposite will probably happen. Wages in low-wage states have been growing faster than those in high-wage states. Under those circumstances, the minimum wage to median wage ratio in low wage states will fall, reducing any potential negative employment effects as a result of the minimum wage hike.

"In the longer run, I think we would do well to consider having multiple federal standards that vary by region: that would mean to reach 50% of median, some places would have minimums higher than 12; others would have minimums that are lower," Dube, who supports tying the minimum wage to either the Consumer Price Index or the median wage, wrote in an email. "Meanwhile, it is reassuring that there has been some regional convergence in the median wages, which reduces the differential bites of a federal standard."

The problem with setting one minimum wage policy on the national level is that policymakers can't account for the variation in state wages. If current wages trends don't change, Murray-Scott would be great for low-income workers. But if it changes—especially if wage growth declines in low wage states—then Murray-Scott would exacerbate the biggest flaws in current minimum wage policy. Democrats must be aware of that risk.

Each successive minimum wage proposal is larger than the previous ones even after accounting for inflation.

To be fair, that’s not an apples-to-apples comparison. Within Turkey and France, certain areas surely have a higher minimum wage to median wage ratios. But it does show that low-wage U.S. states will have worryingly high ratios.