Why Climate Journalists Hate Earth Day

The annual event began with good intentions. Now it’s a source of dread.

The time draws near. Those working in climate and environmental coverage can feel it approaching like the rumble of an oncoming train: Earth Day.

The celebration on April 22 started with the best of intentions in 1970—part of a radical, nationwide movement that also helped establish the Environmental Protection Agency and extend the Clean Air Act. In recent decades, though, Earth Day has felt a bit more nebulous—and susceptible to cliché, pablum, window dressing, and corporate greenwashing. Reliably, at least one oil major each year uses the day to release some bonkers ad copy suggesting they’re environmentalists.

TNR has published several pieces about this long-running trend, from Bradford Plumer’s short post in 2008 comparing the corporate co-opting of Earth Day to Christmas to Emily Atkin’s 2017 classic about Earth Day having become a “corny celebration of green living” mostly for white and privileged people, while low-income and minority populations face toxic air and water every day. Going forward, she wrote, “the onus is on the more privileged classes to change Earth Day from a feel-good exercise for well-off liberals to a day of mass activism to help the underprivileged, who have more immediate concerns than environmental injustice (let alone global warming).”

Liza Featherstone struck a similar note in her plea last year to resurrect the radicalism of the original Earth Day. But on the optimistic side of things, she argued, we can point to the original as powerful proof of concept:

If not for the climate crisis—which scientists and environmentalists warned about on that first Earth Day and the world has struggled and largely failed to address ever since—we’d probably view ’70s environmentalism as one of the most transformative social movements in history. That first Earth Day kicked off many of the important changes. As National Earth Day organizer Denis Hayes said in a 2020 interview, before that first Earth Day the Cuyahoga River was routinely on fire, breathing the air in major American cities like Pittsburgh and Los Angeles was like smoking two packs of cigarettes a day, and the bald eagle—America’s national bird—was in danger of going extinct. None of that is true today. Our waterways are also much cleaner, and fewer children suffer from lead paint poisoning in their homes (in fact, childhood lead poisoning has declined by 90 percent). The massive mobilization of Earth Day helped focus the general public’s attention on the environment, and in turn, that of politicians. Looking at this history tells us something that we need to know right now: We have solved pervasive and deadly environmental problems in the past, and we can do it again.

As part of a series next week on the origin of various environmental culture wars, we’ll have more coverage of how, exactly, this moment of consensus fractured and climate policy got stuck in partisan deadlock. But in the meantime, as we gear up for a week that will doubtless feature its usual share of corporate shenanigans, it’s worth sparing a thought for what meaningful celebration might look like.

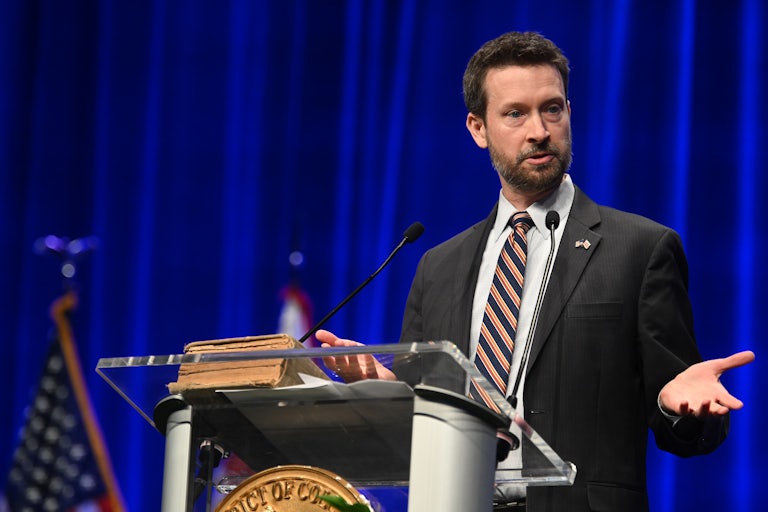

Denis Hayes, the original organizer of Earth Day in 1970, offered five suggestions to Outside magazine’s Heather Hansman last year: Focus on the biggest, and ideally the most discrete, issue (that would be emissions); name a “clear enemy”; pinpoint specific political changes (as when Earth Day activists identified the “dirty dozen” congressmen in flippable districts who were blocking environmental policy); take the imperfect, passable policy over no policy at all; and give people a goal that doesn’t feel “hopeless.”

Notably, none of these sound much like the program you’ll see if you visit EarthDay.org’s rundown for 2023. The official theme is “Invest in Our Planet”—a word choice evoking start-up culture, business-led solutionism, and so-called sustainable investment, none of which have performed all that well in recent years when it comes to reducing emissions. (In any event, the right is now engaged in all-out war on the entire idea that investment should be sustainable.) Under the heading “How to Do Earth Day 2023,” visitors are offered six ideas: “Climate Literacy,” “End Plastics,” “Plant Trees,” “Vote Earth,” “Global Cleanup,” and “Sustainable Fashion.”

If Hayes is right, then for Earth Day to be effective again, it might need to choose one issue. It might need to be more explicitly political and less universally inoffensive. A useful Earth Day might not look like a product you can buy but a fight you can sign up for—and an affirmative vision of what winning the battle might look like.

![]()

Good News

We don’t need the toxic and long-lasting chemicals known as PFAS to make things stain-resistant, a new peer-reviewed study finds. Furniture fabric that hadn’t been treated with PFAS held up just as well as untreated fabric. “PFAS on treated fabric can break off and end up in indoor air, attach to dust, or be dermally absorbed, and the pollution is especially a problem for homes with small children,” The Guardian’s report on the study notes. “The product is commonly applied to stain-resistant apparel and products for babies and children.” Find more information on what we know about the health effects of PFAS here and here.

![]()

Bad News

Sea levels are rising more quickly than predicted along the southeastern and Gulf coasts, which might exacerbate the effects of hurricanes that make landfall there.

Stat of the Week

$14 billion

That’s how much the “collective market value of the biggest US [oil and gas] companies” fell in just three days when Ireland’s parliament voted to divest from fossil fuels, even though the value of the divestment itself (i.e., the value of the stocks in the sovereign wealth fund) was only about $78 million. That seems to indicate, according to a new study reported by the Financial Times, that divestment pledges and “viral divestment tweets” serve as important market signals.

Elsewhere in the Ecosystem

The forest of aspen trees known as Pando, in Utah, is actually a single organism, “perhaps the world’s largest living creature. It might also be the oldest living thing on the planet, having survived for over 10,000 years,” writes Faye Flam at Bloomberg. Each tree is a clone stem of the same plant, all connected by an underground network of roots. But now the organism is under threat:

In the last 100 years, human activity has made growing new stems much tougher for Pando. The main threats, said Rogers, are deer and elk, as well as a few domestic cattle and sheep. Aspen grow fast, which makes their young stems tender and tasty to these herbivores, and so most are getting eaten before they have a chance of becoming a new tree. Areas that used to hold 200 adult stems now have just 50. “It hasn’t shrunk from the outside,” said [Utah State University biologist Paul] Rogers. “It’s thinning and collapsing from the inside.” The fact that it’s getting eaten isn’t the fault of the herbivores. Their populations exploded when, in the early 20th century, people decided to exterminate their main predators—wolves, bears and cougars.

The impact of climate change is harder to predict, said Rogers. “We have these two opposing forces.” On the one hand, warming temperatures could shrink aspen habitat, pushing them to cooler, higher elevations. On the other hand, aspen thrive in fire.

Read Faye Flam’s article at Bloomberg.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)