Five hours into the hearing in Marshall, Texas, moods were devolving fast. “I’ve got rural folks that are sick of seeing solar farms going up on every good piece of ranchland,” growled Texas state Senator Brian Birdwell, hunched over a long wooden dais. Like most of his colleagues, he was gray-haired, drab-suited, ill-humored. Filtering in through a row of tall windows at Birdwell’s back, the December light did little to brighten the atmosphere. “Maybe that’s why we’re gonna be eating insects instead, cause there’s nowhere for the cattle to graze.”

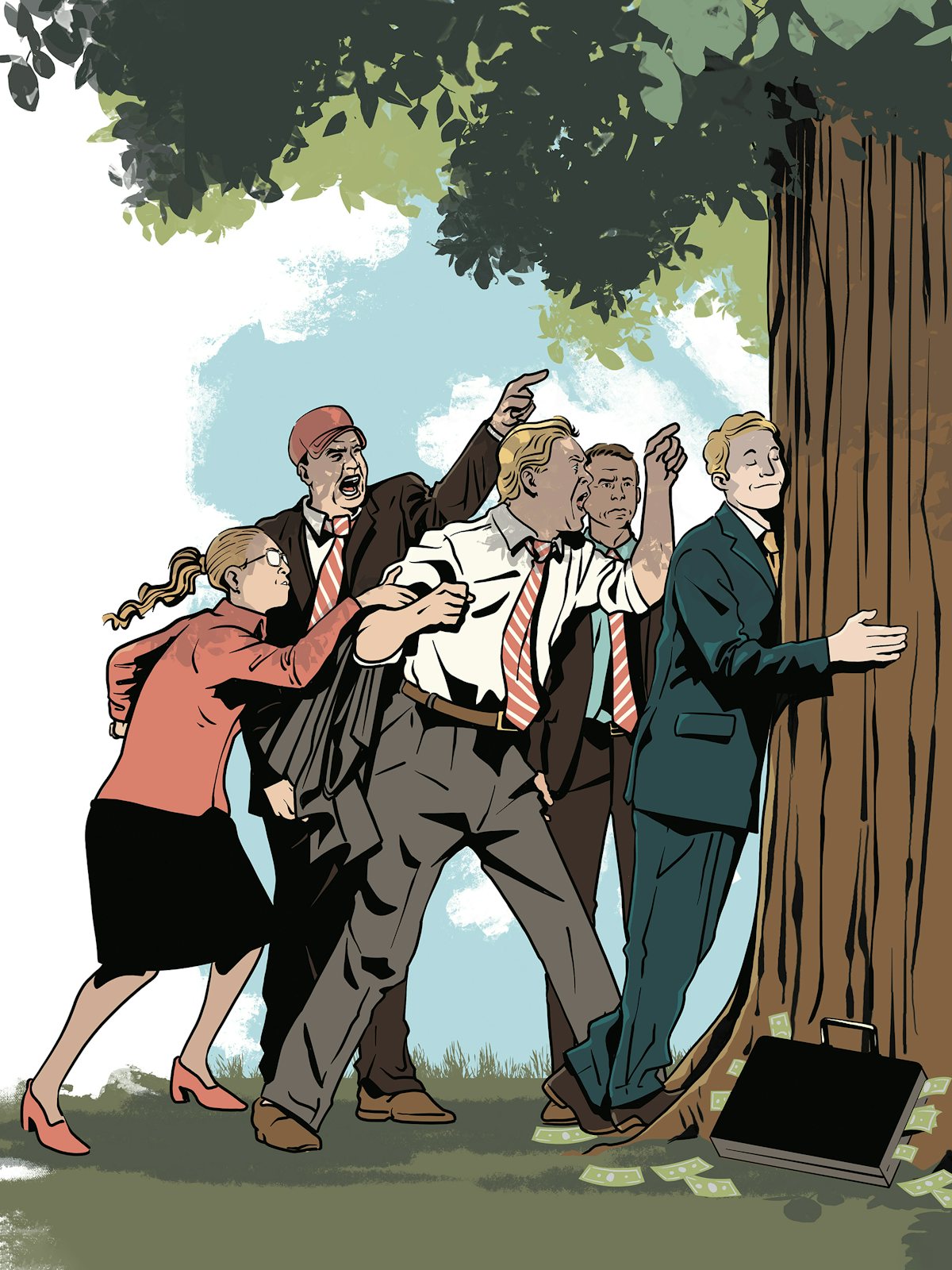

The Texas state Senate State Affairs Committee was considering neither alternative protein sources nor land use. Birdwell and his colleagues were gathered at the Old Harrison County Courthouse to determine whether the asset managers they’d summoned before them—gargantuan companies charged with profitably investing trillions of dollars on behalf of their clients, including the state of Texas—were complying with the demands of a bizarre new law. Passed in 2021, Senate Bill 13 requires Texas to cut off business ties to financial firms deemed to be boycotting energy companies for ideological reasons. The law was just one front in a proxy battle between the Republican Party and three letters newly in its crosshairs: ESG.

The acronym, which stands for “environmental, social, governance,” refers to criteria investors use to determine the impact potential investments may have on the world, as well as calculate how events in the world may affect investments. It can describe financial products crafted to perform well according to those criteria, or strategies corporations adopt to do so. While its meaning is nothing if not fuzzy, the term is often shorthand for climate- and socially conscious investment. Crucially, its emptiness has made it an easy vessel for actors across the political spectrum to fill with meaning. For companies marketing themselves as sustainable, ESG is the means by which the private sector makes the world a better place. For the right, ESG is a new form of wokery, a way of weaponizing other people’s money to coerce corporations to abide by a PC agenda. Not only does so-called woke investing prioritize ideological concerns over returns, conservatives argue, but it threatens to enforce changes far too radical for Congress.

What had set the senators off—rousing them from a post-lunch slump—was a seemingly uncontroversial statement from Dalia Blass, the head of external affairs for BlackRock, which manages a cool $8.5 trillion in assets and has been heavily associated with ESG. Blass had been dispatched to this remote corner of East Texas to endure nearly a full day of grilling, handed the unfortunate task of subbing in for her boss, CEO and right-wing bogeyman Larry Fink. Given his company’s enormous economic and political influence, Fink—a Democrat—has become an easy punching bag for those already prone to arguing that a shadowy cabal of globalist elites is pulling the strings of global governance. Blass was here to absorb a few of the blows. Allegedly, BlackRock wanted to destroy a nearby coal plant. Pressed by committee Chair Bryan Hughes on her employer’s plans, Blass reminded the senators that her company has $170 billion invested in U.S.-based public energy firms and no intention of divesting from them. She reiterated a talking point repeated by her bosses and just about every major fossil-fuel company on Earth (a list that includes donors to most of the politicians glaring at her). “Respectfully, senator, this is about managing carbon emissions, not shutting down plants.”

Senator Bob Hall was incredulous. “You told us earlier that your objective was to maximize investments,” he barked. “Now you’re telling us that your objective is zero carbon emissions. Which is it?” Senator Lois Kolkhorst—who had begun her remarks more genially, cracking a joke about college football in the twang of a fun aunt—framed the issue in apocalyptic terms: “It is my job to let every one of my constituents live the American dream, and I view ESG as doing nothing but marginalizing this country that I have been so blessed to have been born into.”

Over the last two years, deep-pocketed Republicans have encouraged state policymakers to leverage such arguments against everything from banking contracts to new regulations and Democratic appointments. As those fights go national, they might yet eke out a Supreme Court victory that kneecaps the administrative state.

Nevertheless, talk of eating bugs aside, the senators assembled in Marshall had stumbled on to the truth: Getting emissions down to zero will require that companies shut down fossil-fuel infrastructure. The problem is that neither of the main combatants in this culture war is especially interested in doing that.

The fight against ESG extends far beyond Texas. Around the country, numerous states are penalizing banks and asset managers for paying insufficient deference to fossil-fuel companies. So far, five states—starting with Texas—have passed bills to target entities deemed to be boycotting energy companies, and Republicans in more than a dozen legislatures have passed or introduced legislation to otherwise restrict ESG. As the 2023 legislative sessions kick off, additional bills are being introduced by the day. Elected treasurers or comptrollers in Texas, West Virginia, and Kentucky accordingly released blacklists of financial firms they say are engaged in boycotts, calling on them to prove otherwise or lose contracts. Louisiana, Arkansas, South Carolina, Arizona, West Virginia, and Florida have together announced withdrawals of more than $4 billion from BlackRock. Explaining Florida’s decision—which Governor Ron DeSantis signed off on—Jimmy Patronis, the state’s chief financial officer, called it “undemocratic of major asset managers to use their power to influence societal outcomes.”

Building on these legislative successes, Republicans have vowed to use their newfound control of the House to force ESG-friendly asset managers to answer for their alleged crimes, not least with hearings like the one in Marshall. Their other plans are grander, and may result in dramatic changes to the administrative state. In July, Patrick Morrisey, the West Virginia attorney general, rallied his counterparts in more than 20 other states—all members of the anti-ESG broad front—to argue that a proposed climate disclosure rule from the Securities and Exchange Commission violates major questions doctrine, which holds that federal agencies have a limited ability to interpret and act on congressional statutes. That case, likely to make its way to the Supreme Court, could indefinitely hamstring the government’s ability to function.

Undergirding the anti-ESG movement is a familiar network of right-wing think tanks receiving hearty backing from some of the same donors that supported an earlier generation of self-described climate skeptics. One leading player is the Texas Public Policy Foundation, which was instrumental in passing that state’s anti-boycott bill. In 2021, former Texas state Representative Jason Isaac, who leads the organization’s anti-ESG work, unsuccessfully pushed the American Legislative Exchange Council (the ostensibly nonpartisan group of state legislators known for blanketing state Capitols with near-identical bills to advance right-wing priorities) to adopt a copy of Texas’s law as official model legislation, the “Energy Discrimination Elimination Act.”

Isaac tried again last year, this time with a revamped measure drafted by “a coalition of folks” that included an ALEC staffer; Trump’s failed nominee for labor secretary, Andy Puzder; and Derek Kreifels, the CEO of the State Financial Officers Foundation, whose nonprofit network of state treasurers and comptrollers has served as a central coordinating hub for anti-ESG efforts. The resulting “Eliminate Economic Boycotts Act” bars companies with more than 10 full-time employees that want to do business with a given state from taking “social, political, or ideological interests” into account when investing.

To coordinate messaging among treasurers and comptrollers, SFOF has contracted with CRC Advisors, a for-profit PR shop part-owned by right-wing legal crusader and Federalist Society guru Leonard Leo. Legal entrepreneurs and ESG opponents have found common cause elsewhere, too. The Center for Media and Democracy—a watchdog group that has tracked state-level anti-ESG efforts since their inception—confirmed in January that the Republican Attorneys General Association’s Rule of Law Defense Fund, which was active in rallying Trump supporters to the Capitol on January 6, 2021, now has an “ESG Working Group.”

The money for the fight against ESG is coming from familiar sources. One of the largest sponsors of the State Financial Officers Foundation is Consumers’ Research, a 501(c)3 that between 2013 and 2019 received $4 million from DonorsTrust and Donors Capital Fund, dark-money groups that have funneled money from anonymous donors on to outfits pushing—among other conservative fixations—climate denial. DonorsTrust’s 2021 tax returns show a number of other generous gifts to groups attacking ESG: $191,600 to ALEC; $493,000 to the Texas Public Policy Foundation; $934,500 to the Heartland Institute; and $360,000 for the Heritage Foundation.

Like the older-school climate denial it’s replaced—advanced by a dwindling network of old men who insist simultaneously that the earth is not warming and that climate change is good, actually—the jumble of anti-ESG talking points spreading through state capitals, right-wing think tanks, and congressional offices is an incoherent mess. The supposedly too-woke BlackRock has $107 billion invested in Texas-based energy companies alone, up from $91 billion in February 2022. At the hearing in Marshall, when Senate State Affairs Committee Chair Bryan Hughes was reminded of BlackRock’s sizable fossil-fuel investments, he countered confoundingly that the problem is that BlackRock has not divested. After BlackRock’s Dalia Blass noted her company’s $27 billion investment in ExxonMobil, Hughes responded gravely. “That’s our concern, we wish you weren’t there,” he said, then clarified: “We wish BlackRock didn’t have such a big stake in Exxon to push them around, bully them, and vote against oil and gas exploration.”

Hughes argues that asset managers’ undue influence is exercised through proxy votes, the decisions shareholders make about corporate strategy and management at companies’ annual general meetings. Yet Hegar, the Texas comptroller, did not even consider proxy voting behavior when drafting up his list of the 10 banks and asset managers banned from state contracts for boycotting energy companies.

The right’s success in dragging ESG into the culture wars is owed in large part to the confusion about what those letters actually mean. Even the corporate staffers and Wall Street types most likely to know what ESG stands for (again: environmental, social, governance) don’t share a common definition; three-quarters of institutional investors admit to being unclear. It does not, after all, make intuitive sense to refer to a jumble of adjectives as a noun—let alone a tidily nefarious approach to investing.

As legal scholar Elizabeth Pollman notes in her genealogy of ESG, the concept emerged out of the defeat of left-leaning plans in developing countries to rein in transnational corporations. Through the era of decolonization, nations freeing themselves from colonialism looked to build economic independence by constraining corporations that had long functioned as official or unofficial outgrowths of the old colonial powers; a key aim was to assert sovereignty over natural resources within their borders that had made fortunes for executives abroad. That push came to a head in the 1970s, only to be snuffed out by the early 1980s. Gradually, the United Nations adopted a more corporate-friendly orientation, pursuing public-private partnerships in line with the neoliberal zeitgeist. In 2000, it launched the Global Compact, a collaboration with the financial sector wherein companies signed on to an initial set of nine nonbinding principles on human rights, labor, environment, and anti-corruption.

In an influential 2004 report dubbed “Who Cares Wins,” the Global Compact coined the phrase ESG as a strategic rebranding of those priorities, calling for “better inclusion of environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) factors in investment decisions.” The explicit goal, it must be emphasized, was to maximize profits. Companies that scored well on ESG metrics, the report stated, could “increase shareholder value by better managing risks related to emerging ESG issues, by anticipating regulatory changes or consumer trends, and by accessing new markets or reducing costs.”

ESG, of course, still lacks a formal definition or comprehensive regulatory oversight. It might mean taking a hard-nosed look at whether a company is poised to take advantage of or suffer from emerging trends like electrification, offering a niche product, or making a wan declaration of do-goodery. On a short-lived podcast put out by the State Financial Officers Foundation, Gallantly Streaming, foundation CEO Derek Kreifels offered his own creative interpretation: “BlackRock is the Death Star. The progressive ESG movement is the Evil Empire. President Biden could arguably be Darth Vader, and the emperor is Larry Fink.”

What can perhaps be agreed on is that a firm’s embrace of ESG indicates a certain willingness to adjust to shifting cultural mores, regulations, and even physical environments in ways that clients and investors might find attractive. It is arguably good for Disney’s bottom line to diversify its corporate leadership and, consequently, content offerings—an action that would fall under governance, or “G.” For Ikea, fashioning pillowcases out of toxic materials in sweatshops is a bad look, even if it happens to be cheaper. As such, the company widely broadcasts its commitment against those practices, a strategy that might fall under the social (“S”) umbrella.

Hedge funds have a similar incentive to determine whether luxury beachfront properties they might want to snap up will stay above sea level for more than a decade. Generally understood to include assessments of climate risk, investments in decarbonization and resilience, and the sustainable investment products banks and asset managers offer to retail and institutional customers, environmental, or “E,” is the broadest and most controversial adjective of the trio. ESG critics on the left—by far the loudest historically—fear such methods can lull policymakers and the public into a false sense of security that the private sector is independently taking care of the problems it causes and doesn’t need stricter state oversight.

That fear has been largely vindicated.

Republicans’ claims notwithstanding, the banks and asset managers coming under fire from red states continue to invest prolifically in the fossil-fuel industry. In 2021, sixty banks worldwide poured $185.5 billion into the 100 most expansionary fossil-fuel companies. JPMorgan Chase—targeted by both Kentucky and West Virginia for boycotting energy companies—provides more funding to fossil fuels than any other bank on Earth. Between 2016 and 2021, it furnished no less than $382.4 billion to coal, oil, and gas companies. According to a 2023 report from watchdog groups, the “Big Three” asset managers (BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street) together hold $460 billion in fossil-fuel holdings. Just one of the asset managers the report analyzed has a policy restricting financing for new oil and gas development. Among signatories to the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero—an effort to corral financial institutions to act on climate—BlackRock is the largest investor in fossil-fuel expansion, with $23 billion in stock and bond holdings in coal developers. (BlackRock declined to be interviewed on the record for this story.)

Despite its obvious commitment to fossil fuels, BlackRock in particular has heavily marketed itself as a climate champion. In 2018, Larry Fink began writing annual letters to CEOs and clients to extol the virtues of stakeholder capitalism and of looking beyond short-term returns. Hotly anticipated every year by the business press, the letters lay out Fink’s investment approach and perspective as the head of a company whose now trillions of dollars’ worth of shares—spanning the whole economy—offer a purportedly more enlightened view than that of the provincial corporate manager. “To prosper over time,” Fink wrote in his inaugural 2018 letter, “every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society.” His 2020 letter called climate change “a defining factor in companies’ long-term prospects” and pledged to hold them accountable. BlackRock, he added, “will be increasingly disposed to vote against management and board directors when companies are not making sufficient progress on sustainability-related disclosures.”

Tariq Fancy joined the company to help it in that high-minded mission, coming on as BlackRock’s chief investment officer of sustainable investing in 2018. Affable and photogenic, with more than a few choice catchphrases at the ready, Fancy had previously left a private equity job doing “vulture investing” in emerging markets to found an educational technology nonprofit. A little less than two years after his arrival at BlackRock, Fancy, who is now 44, left to attend to family matters. Since that time, he’s emerged as a high-profile critic of ESG, making the rounds as a speaker and commentator on sustainable investment while splitting time between New York and his hometown of Toronto.

In a widely circulated Medium essay about working at the asset manager, Fancy—who speaks with a slight Canadian accent—describes flying back from a conference on a private jet with two colleagues working on iShares, BlackRock’s massively profitable line of low-fee exchange-traded funds, or ETFs. When discussing how precisely the team’s recently launched low-carbon ETFs would contribute to fighting climate change, one colleague was exasperated. “All they need to know is that it has a lower carbon footprint!” Fancy recalls her saying.

After leaving BlackRock, Fancy thought of its sustainable investment business as irrelevant to fighting climate change but pretty harmless. Mostly, he told me, “I didn’t want to be a salesperson for ETFs.” However, seeing how quickly the public and private sectors sprang into action around the pandemic, he started to see it as something worse. The speed with which industry leaders followed the advice of epidemiologists pointed up how slow they had been to listen to climate scientists. “Green investing is actively harmful because it’s influencing public opinion and lowering the likelihood of regulation,” he argued. “It’s like giving wheatgrass juice to a cancer patient. It’s being so hyped and over-marketed. There’s clear evidence the patient is delaying chemo.”

According to Fancy, BlackRock does take the risk posed by climate change seriously insofar as it impacts the company’s bottom line. But no one seemed to notice that assessing climate risk “isn’t the same as fighting climate change,” he said. “We’re trying to get our money out before it hits. There’s no social impact created out of selling something to rich people to protect their portfolio.”

Given his former employer’s shortcomings, he’s been baffled to watch the rise of the movement skewering BlackRock for its supposedly radical environmentalism. The right argues that asset managers are placing their values above customer returns; Fancy dismisses the idea out of hand. “They’re not violating fiduciary duty because they can’t,” he told me. “This is green paint on what they’re already doing. And suddenly these guys appear from the right pretending this green paint is actually real.”

What’s more, specifically ESG-themed funds like those Fancy sold remain a small sliver of what the largest asset managers offer. The biggest moneymakers—most of what state and municipal government clients buy—are algorithmically managed passive index funds such as ETFs, pegged to established listings like the NASDAQ. Thanks to their low management fees and investors’ hunt for yields amid record-low interest rates, such funds have exploded in popularity in the years since the Great Recession. In 2009, BlackRock controlled $3.3 trillion.

When Republicans rail against firms for enforcing ESG, they generally refer to companywide policies about analyzing and managing risks that climate change and an energy transition could pose to portfolios. They take aim, as well, at asset managers’ membership in investor alliances like Climate Action 100+ and the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero. To opponents, the Big Three asset managers’ massive control of corporate shares—BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard together own 20 percent of the average S&P 500–listed firm—awards them outsize power to enforce the whims of supposedly nefarious global alliances.

In contrast to the industry’s more soaring messaging, any agenda invoked by asset managers in the boardroom is purely in service of profits. “For the asset managers, these are just products,” said Benjamin Braun, a political scientist at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne, Germany. Their core business model is retail, not returns: They aim to bring in ever-more fee-paying customers. The performance of any individual company or industry matters only if it poses a barrier to retaining and attracting clients. “Asset managers first and foremost are for-profit businesses that try to manage as much money as possible for as little cost as possible,” Braun said. “Anything they have to do in terms of engagement or corporate governance is a cost because you need to hire people that do that.”

That ambivalence about engaging with corporate governance is part of what makes the GOP’s campaign against ESG such a headache for major asset managers. In response, BlackRock has expanded its Voter Choice program. Index fund investors representing $1.8 billion can now opt to cast the votes their BlackRock–managed shares entitle them to in corporate boardrooms rather than having the company vote on their behalf; State Street has launched a similar program. So long as there are interested customers, asset managers see little contradiction between making returns on fossil fuels and making returns on the still vaguely defined transition away from them. The company is perfectly happy to bring in clients interested in both ends.

After all, as the United States and Europe compete over how many billions of dollars in annual subsidies they can offer to renewable energy developers and electric vehicle manufacturers, there is a tremendous amount of money to be made by emphasizing environmental concerns. By 2025, ESG assets are projected to become a $50 trillion market and account for a third of all assets under management worldwide, boosted by government support for green energy and technologies. Asset managers can take advantage of that green wave demand by offering novel ESG investment products. And through its growing real assets and private equity arms, BlackRock can also invest directly in energy and infrastructure projects now eligible for a suite of new incentives. The public sector will shoulder the risk of new green asset classes as the private sector reaps the reward; whether emissions decline as a result is, for asset managers, irrelevant.

An irony of the Texas senators and other “anti-ESG” stalwarts claiming their fight is one in defense of the fossil-fuel industry is how enthusiastic fossil-fuel companies themselves are about ESG, often through watery, far-off “net-zero” commitments that rely on unproven technologies to swallow up excess carbon from a rebranded business as usual. Chevron—a donor to Texas state Senators Kolkhorst and Hall—proudly touts its ESG commitments, from biodiversity to human rights and cybersecurity. After the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, oil and gas executives, like Fink, raved about the opportunities new tax breaks presented for technologies such as carbon capture and storage and hydrogen.

As states demonize banks and asset managers over their climate rhetoric, they could also be starving energy companies of investment partners. In a letter to Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar, Matt Vining, CEO of the oil field services company Navigator Energy Services, urged him not to include BlackRock on the state’s list of blacklisted companies. “Contrary to recent headlines, BlackRock does not boycott the oil and gas industry,” Vining wrote. He praised the company as “an essential partner,” noting its partnership on a carbon-capture pipeline system that could feasibly benefit from IRA tax breaks.

The rhetorical strategy of the anti-ESG movement relies on taking years of green marketing at face value. As the right throws their own talking points back at them, BlackRock and its peers are being made to straddle between the customers who want them to pursue ESG goals and those broadcasting to millions of viewers that such goals are, as Elon Musk once tweeted, the “Devil Incarnate.”

Few have pushed the line that ESG is the devil more loudly than Vivek Ramaswamy, who runs the asset management firm Strive, backed by the likes of Peter Thiel and the hedge fund Narya Capital. Rarely photographed without a well-tailored blazer and crisp, precisely unbuttoned white shirt, the former wunderkind biotech executive is the author of Woke, Inc.: Inside Corporate America’s Social Justice Scam. Ramaswamy has also written prolifically on ESG and topics popular on the conservative-speaker and talk-show circuit, from big tech censorship to victimhood. He made sure to inform me of that fact a few minutes after we hopped on the phone. “Read basically every op-ed I’ve written in The Wall Street Journal this year,” he advised. “I think it will bring you up to speed on this entire subject pretty quickly.”

Ramaswamy defines ESG as the “use of nonpecuniary factors to guide investment decisions, investment oversight practices, and investment manager selection”—in other words, the practice of making decisions about investments for purposes other than generating the best returns, which he views as a dangerously anti-democratic distraction from corporations’ true purpose of maximizing shareholder value. Sure, liberal fund managers are free to do what they want with their money—“that’s part of what it means to live in a free country and a free economy,” he said. “The problem is when large financial institutions are using other people’s money to advance considerations that they did not consent to.” Ramaswamy’s solution is to encourage “transparency, disclosure, and consent” from capital owners (e.g., pensioners whose funds asset managers invest). He also suggests using all available tools to hold financial institutions to the sole interest rule, the fiduciary law establishing that trustees must consider only the interests of their clients.

“Ask any everyday American who has money invested in the market: Do you want your money to be used to vote in favor of a racial equity audit?… I think most Americans,” he contended, “will give you a clear answer: Hell no!” (Sixty-three percent of Americans, however—and 70 percent of Republicans—think the government should not set limits on corporate ESG investments.)

Ramaswamy, who has keynoted confabs for the Heritage Foundation and the State Financial Officers Foundation, pushed back on the notion that there was any anti-ESG movement at all. While ESG was “one of the most powerful movements in capital markets over the last decade,” he described the recent pushback against it as a “smattering of arguments” “heavily influenced” by his book. Emails obtained through diligent public information requests by the watchdog group Documented show a small, well-funded network of conservative actors—including Ramaswamy—coordinating to enlist state fiduciaries and pension funds against ESG. He and Strive employees have spoken with elected fiduciaries and pension board decision-makers in Missouri, Alaska, South Carolina, West Virginia, North Dakota, and Utah, and attended strategy meetings with organizations working to advance anti-ESG measures.

In some cases, they talked about investment opportunities; Ramaswamy appeared to be trying to drum up business for Strive from politicians advised to divest from BlackRock and its peers. When we spoke on the phone, Ramaswamy said Strive was actively seeking out new pension fund clients, trying to compete with BlackRock and “go after the same distribution channels.” (Strive was once code-named “WhiteStone.”) In a follow-up email, he noted that none of the states whose officials he had spoken with had invested assets into Strive products. “Strive’s clients have come mainly through retail channels,” he said.

State officials have raised concerns about the ethics of taking advice from someone with a financial interest in their decision-making. In discussing whether to invite Ramaswamy to speak to an educational meeting for its board in June, staff at the Missouri State Employees’ Retirement System appeared to caution against the idea, given that Ramaswamy had disclosed he was setting up Strive. “My thought is we want to keep this meeting to education and not include someone who is actively recruiting investors for a fund,” Ronda Stegmann, former executive director of the Missouri State Employees’ Retirement System, wrote in an email. However, Ramaswamy did end up presenting. The day after, the board agreed to instruct BlackRock not to vote on its behalf, knowing the change would raise administrative costs. Less than a week after recruiting Ramaswamy to speak to the South Carolina Retirement System Investment Commission and the state’s Republican legislative caucus, Curtis Loftis Jr., the treasurer of South Carolina, announced a $200 million divestment from BlackRock.

States investing assets with Strive aren’t the only potential revenue stream Ramaswamy could extract from the anti-ESG movement. He has also spoken with a number of state officials on proxy voting and shareholder engagement through Strive’s recently announced advisory arm. That venture is pitched as an explicit alternative to allegedly woke proxy advisers like Institutional Shareholder Services, which was also called to the hearing in Marshall. Emails show that Strive was on the verge of inking its first contract with a state pension system—the name of which was not mentioned—last fall. Ramaswamy pitched a similar arrangement to North Dakota.

Advisory materials circulated and written by Strive consultants suggest that pension boards exercise a preference for asset managers that sound a lot like Strive. On August 2, Ramaswamy sent Lucinda Mahoney, the former Alaska revenue commissioner and a member of SFOF, a list of best practices for state pension boards, drafted “by a legal academic, in conjunction with our team, who also works as a consultant for Strive.” The document recommends terminating pension board contracts with “pro-ESG” asset managers that cannot prove their practices “lead to financially superior returns,” and further counsels pension funds to exercise a preference for asset managers “found not to have pro-ESG voting and corporate engagement policies.” Just over a week later, Strive launched its inaugural fund, DRLL. (They now offer seven other ETFs.) Mahoney emailed Ramaswamy her good wishes: “Congratulations!!!! Well done!”

According to a promotional video starring Ramaswamy, DRLL’s big idea is to use investors’ power as shareholders to fight back against the Big Three asset managers allegedly telling U.S. energy companies “to produce less oil and to frack for less natural gas.” DRLL will instead mandate them “to drill more, to frack more, to do whatever allows them to be more profitable over the long run without worrying about these toxic political agendas in the boardroom.” Strive’s sales pitch for the fund lists boosting energy exploration and production as a top goal. By buying DRLL, Ramaswamy said, you can “join the movement.”

Fancy doesn’t see much daylight between what BlackRock and Strive are doing: In essence, both are signaling different virtues to different customer bases. “Strive Capital in particular is realizing that ESG products are a price-segmentation strategy for progressives,” he told me. “They could agree with me and say it’s all marketing and none of it needs to exist and there are other ways to solve that problem. But that’s the last thing they want. So they just start pretending the ESG thing is real.” He likened Strive to Black Rifle Coffee, founded to serve “people who love America.” The roaster’s trollish presence online and at gun clubs has endeared it to armed white supremacists. Yet if Black Rifle is presented as an alternative to the liberal scolds at Starbucks, Strive, given its modest $500 million in assets under management and relatively niche offerings, makes for an odd replacement for either ISS or a Big Three asset manager—at least for the state pensions and fiduciaries Ramaswamy is talking to.

The argument from Ramaswamy and his fellow travelers is that liberal states are pressuring asset managers to advance a climate-oriented agenda, when asset management, in their view, should be agenda-free. New York City and California, both of which have demanded firms set stronger climate targets, have “pressured the BlackRocks of the world into using everyone else’s money to also advance that same objective,” Ramaswamy said. Of course, the anti-ESG cohort is advancing its own agenda with similar means: using states’ market power to enforce companywide policy among monopolistic asset management firms. What is the difference? Do people whose states might invest their pensions with Strive have any way of learning about that or weighing in on its proxy voting and shareholder engagement practices? When I put these questions to him, Ramaswamy expressed some ambivalence about the anti-boycott bills he has publicly supported. “We believe the right solution is more competition and disclosure in the market,” he insisted. And with regard to Strive, he emphasized the need for transparency “when there’s a nonpecuniary investment,” though he didn’t clarify who would make the call on what counts as nonpecuniary.

A throughline of anti-ESG activism is its single-minded commitment to fossil-fuel production that in some cases reaches well beyond what companies actually seem to want, even as the American Petroleum Institute provides backing. At the North American Gas Forum in Washington, D.C., this fall, an oil executive—speaking on the condition of anonymity—was weary of the push. “Those are still fundamentally decisions that need to be driven by the businesses,” he said.

If parts of the fossil-fuel industry seem uneasy or ambivalent about the anti-ESG crusade, parts of the financial sector are livid. Emails obtained by Documented show a tense back and forth between West Virginia Treasurer Riley Moore’s office and the West Virginia Bankers Association in the drafting process for SB 262, an anti-boycott bill modeled on the one passed in Texas. (Moore’s office did not respond to multiple requests to comment on this story.)

Provided a draft of the bill to mark up, the West Virginia Bankers Association general counsel and director of government relations, Loren Allen, objected to the bill’s intrusion on free-market principles. It was unacceptable to the banking industry, he wrote in a comment, that WVBA members could be punished for any perceived slight against a company: “Banks are being put in the onerous position of having to justify every decision they make in this regard” to the West Virginia State Treasurer’s Office. Allen noted, as well, that the draft contained no provision that grants a listed financial institution the right to know what evidence exists for a boycott, “leaving the adversely affected bank defending against unknown, unsubstantiated information provided by unknown sources.”

While it agreed not to publicly oppose the bill, the West Virginia Bankers Association sent a strongly worded letter to Moore expressing its frustration: “One key point upon which all banks agree is that the logic of this type of legislation is inherently and deeply flawed. Our banks must not be used as pawns to impose political strictures upon the free market regardless of the ideology behind it.”

If the right’s crusade against ESG reflects a flexible relationship to free-market principles, it has a downright hostile attitude toward democracy. Increasingly, the right’s more authoritarian tendencies are unmoored from arms of capital traditionally friendly to right-wing causes. Where ideological libertarians look to build momentum for a Supreme Court challenge to the administrative state, corporate managers want to fight back against the asset managers calling ever-more shots. Fossil-fuel companies, meanwhile—especially smaller firms finding it harder to cash in on either decarbonization or surging gas prices—are struggling to maintain a twentieth-century business model. All that desperation and anger is fertile ground for wealthy and ideologically hard-line donors and activists with millions to spare on enlisting new recruits in old fights.

BlackRock is an easy punching bag, of course. And a handful of asset managers’ outsize power to shape corporate policy is troubling for reasons that have nothing to do with some imagined woke agenda. As politicians increasingly lean on the private sector to deliver climate solutions, Wall Street’s one and only priority is still to turn a profit. Absent robust public investment of the sort that now seems unlikely in the United States, ceding planning decisions for an energy transition to banks and asset managers means that projects that aren’t profitable simply won’t get funded. Still, the world envisioned by Texas-style anti-boycott bills is nightmarishly authoritarian: where offending a fossil-fuel company triggers government sanctions. If the center stage battle over climate policy in the United States becomes one fought between ALEC and asset managers, then democracy has already lost.