About a year after I completed my Ph.D. in modern literature, during which time I’d had no luck landing employment, I approached a well-known literary scholar for his counsel. “Greg,” he said conspiratorially, “have you ever thought about working for the company?” “Dr. ___, I don’t really want to go into private industry.” “No, Greg; I mean the company. I can get you in.” Gobsmacked, I thought to myself, This guy doesn’t know his audience. Neither our politics nor my skills. Hard pass.

My assumption that humanist academics were all on the left was foolish, of course. But so was my defeatist certainty that grad school hadn’t trained me for anything useful. In fact, as Elyse Graham shows in her snappy and entertaining Book and Dagger: How Scholars and Librarians Became the Unlikely Spies of World War II, humanists and their comma-hunting, cross-referencing, collecting, and cataloging ways made pivotal contributions to America’s war effort in Europe, and may well have ensured its success.

With few exceptions, these scholar-spies did their work not in the uniformed branches but in the Office of Strategic Services, or OSS, the precursor to the CIA and the country’s first dedicated intelligence agency. Officially created about six months before Pearl Harbor and led by the World War I hero General “Wild Bill” Donovan, the OSS was initially an information-gathering and analysis agency, but by mid-1942 had expanded into “operations”: spy work. The book’s central figures are Joseph Curtiss, a “mild-mannered English professor from Yale”; Adele Kibre, a University of Chicago classicist; and the blustering and profane, not-at-all-mild-mannered Yale history professor Sherman Kent, who later held a high national security position in the Eisenhower administration, though Graham also recounts the stories of dozens of others librarians, archivists, mathematicians, and anthropologists who lent their brains to the OSS.

Although we likely picture ingenious feats of deception and infiltration when we think of the OSS, in this book Graham persuasively argues that the spy agency’s most consequential achievements were in fact its innovative and resourceful methods of collecting, organizing, and weaponizing information, much of which was already publicly available. “There was no way,” she claims, that the OSS could have caught up to its much more experienced rivals and adversaries when it came to spy work, so instead “they reinvented intelligence” by finding information that others dismissed or ignored and letting the tweed brigade work their wonders on it. These scholar-spies “expanded—dramatically—what counted as intelligence and what kind of person would make a good spy.” In so doing, the OSS reshaped espionage in ways that would later influence the design of the CIA and other intelligence-gathering agencies during the Cold War, and did so in “the American way: welcoming strangers, seizing the practical gains of diversity, finding common cause between aristocrats and thieves.” It was the humanists, in other words, who won the war.

Adele Kibre was, Graham claims, “the Allies’ greatest agent.” In 1942, the OSS sent Kibre to the American legation in neutral but German-leaning Sweden, ostensibly on a book-collecting mission for the Library of Congress unrelated to the war. That wasn’t far from the truth, as her actual job was to hoover up literally everything printed she could find, everything the Swedes and Germans were putting into circulation, internally and within the occupied territories.

“Microfilm copies of entire newspapers … scientific journals that Allied scientists could no longer acquire, underground newspapers from Norway, secret photographs of sabotage in Occupied Europe” all found their way to Kibre’s pouches. With experience as a Hollywood actress and a cover as a tunnel-visioned librarian, Kibre could charm just about anything out of her targets. (As the recent film Oppenheimer dramatizes, one of those scientific journals revealed to the Manhattan Project scientists how the atom had been split.) But she wasn’t just collecting obviously strategic material; the OSS wanted even the most mundane and banal publications, such as atlases, telephone directories, business registries, banking regulations, metallurgical and chemical journals. Why? “Because,” Graham points out, “the right piece of paper, in the right hands, might hold the secret to winning the whole war.” And the United States really didn’t have much of the information it would need to fight an overseas war. In 1941, for example, “the whole of the U.S. contained only two portfolios of maps showing all of Japan.”

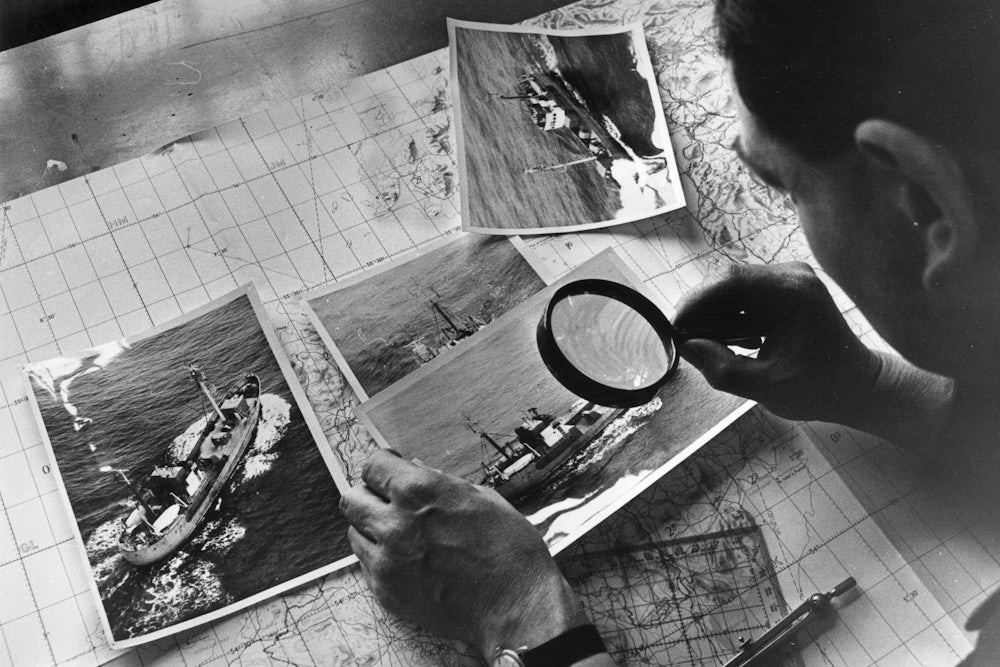

But how to turn this mass of data into useful information? That was the job of the so-called “chairborne division,” the heart of the early OSS. Initially housed in one E Street complex near today’s Kennedy Center, and later in buildings and Quonset huts across Washington, OSS’s Research and Analysis Division, or R&A, was an entirely new innovation in intelligence: an enormous team of researchers and eggheads “pulled … from humanities departments in universities” and told to do their thing. Officials dumped all of the material gathered by Kibre, Curtiss, and others on these professors and told them to find out, for instance, which Swedish plants were manufacturing—and selling to the Nazis—ball bearings, where those plants were, and who their employees were, so Kibre or someone like her could trick a middle manager to share an annual report. They asked them to figure out whether the Allied estimate of German tire production was correct. (No, it was overstated by a factor of five, and 70 percent of that was from just five vulnerable factories.) Or they just let these intellectuals act naturally and sift through all of these papers, maps, and magazines to try to find patterns, rhymes, significance.

R&A insisted “that you can get vital combat intelligence from all kinds of unpromising sources” and so pulled “usable intelligence on every aspect of the war from the snips and scraps that crossed their desks.” A society column in a local newspaper might offer clues to the location of a hidden German unit, or changes in a freight-rail timetable might indicate which munitions factories were ramping up production. This was scholarship, just on different primary texts. “The central conceit of intelligence analysis,” Graham explains, “is that intelligence work should follow the university model … with analysts working separately from policymakers and striving for the highest degree of objectivity.” And the OSS was, she claims, the first intelligence agency anywhere to reach out to the people who did this kind of research for a living. Graham does, though, dismiss Donovan’s patronizing postwar praise of his “amateurs in intelligence.” Scholars like Curtiss, Kent, and Kibre “weren’t amateurs,” she insists. “They were experts in intelligence. It’s just that the intelligence world didn’t know it yet.”

I’d add to Graham’s roll call another Yale scholar-spy, Norman Holmes Pearson. (Alec Baldwin plays a character partly inspired by Pearson in the 2006 Matt Damon film The Good Shepherd.) Pearson, whose biography I have just published, appears nowhere in Graham’s book but was as important a member of this crowd as Kent, or Kibre, or Curtiss. In fact, when the OSS needed a tweedy academic to do Kibre-style work in Switzerland, Pearson—who studied the works of Nathaniel Hawthorne—was their first option; Curtiss ultimately got the post because his German was better. In the spring of 1943, Donovan plucked the preternaturally shrewd and ingratiating Pearson from his R&A desk and flew him to Ayot St Lawrence, near the British intelligence hub at Bletchley Park, where he and three other men designed “X-2,” the OSS’s counterintelligence branch.

The British had demanded the creation of an independent X-2 as a precondition for sharing the “ULTRA intercepts,” information gleaned from breaking the German Enigma code machine, because the upper-class toffs who dominated British military intelligence didn’t trust bumbling American spies not to tip their hands. In his two postgraduate years at Oxford, Pearson had learned how to mix the perfectly blended cocktail of imitation and deference that English aristocrats responded to, and so as head of X-2 became the primary channel through which this invaluable intelligence made it to the American brass (even as his airs got under Kim Philby’s skin).

Like his friend Curtiss, who ultimately would report to him, Pearson applied his lit-scholar skills in the service of his country—after all, analyzing ink and paper stock to determine whether an intercepted letter is real or a plant isn’t all that different from assessing which of several drafts of a Hawthorne story was the author’s final one. And like his colleague Kent, Pearson also helped meld elite academia and the national security state in the early Cold War. For many years he was the primary recruiter of Yale men (English and American Studies majors, mostly) for the CIA, ensuring that humanists and their methods would continue to guide American intelligence gathering and analysis. (And for years the CIA used the training program he designed while in OSS to prepare its new counterintelligence agents.)

Kibre, Kent, Curtiss, Pearson, and the rest didn’t just find intelligence gold where nobody else was looking. The OSS and its grab-bag, try-anything, humanist approach proved far more agile and able to process and react to contradictory information than the conformist, closed system the Nazis built. “Authoritarianism is a catastrophic intellectual handicap,” in the scholar Robert Hutchings’s words, for ultimately it is only the Leader, or the ideology, that determines what is true and what is not, what is of use and what is useless. Any seeming “facts” that contradicted Nazi ideology—about the inadvisability of invading the USSR, for instance—were seen as lies or plots to undermine the Führer.

Hitler also reviled what he called Tintenritter, or “ink knights”: academics, writers, librarians. What could they offer to the mighty Wehrmacht? As it turns out, the seemingly pointless and definitely un-martial labor of OSS’s scholar-spies and the Chairborne Division gave the U.S. essential intelligence about German infrastructure—the kind of intelligence that Graham writes the Nazis never bothered to develop about Britain, and that would have made its bombing raids even more devastating.

Hitler and the Nazis, of course, predicated not just their rule but their epistemology on excluding the ideas and work produced by those of “inferior” races and ethnicities. The Nazi purge of Jewish scientists and “Jewish science” ensured that the U.S. would win the race for the atomic bomb. But at least in Graham’s telling, the OSS gladly welcomed anyone who could help. Dozens of naturalized Americans and refugees from Hitler’s empire (like the Romanian statistician Abraham Wald, whose equations showed the Army Air Corps how to better armor its planes) enter Graham’s story, making crucial contributions to intelligence gathering and analysis. As opposed to the uniformity and intellectual homogeneity of the German intelligence services, such as the Sichhertsdienst, the OSS was built to capitalize on America’s diversity and openness to immigrants. In Donovan’s own words, “The vast pool of linguistic skills and special racial and regional knowledge became one of our prime assets.”

There is something undeniably Hollywood about Graham’s conclusions about what made the U.S. approach to intelligence so successful. The OSS’s successes came from the ingrained American traits of pragmatism, cleverness, making-do, “reckless optimism and confidence,” and diversity. Quite a few ragtag bands of misfits who succeed against all odds populate Book and Dagger, and why not? It’s always been the movies’ story about America’s World War II success in Europe, from Oppenheimer through Inglourious Basterds, Saving Private Ryan, Kelly’s Heroes, all the way back to 1945’s A Walk in the Sun. But perhaps it’s time for Hollywood to tell the story of the scholars and archivists who made victory possible, set in a reading room or in front of a wall of card-catalog shelves, for as Graham concludes, “the war may have been fought on battlefields, but it was won in libraries.”