When Kamala Harris and Donald Trump meet tonight to debate at Philadelphia’s National Constitution Center, they probably won’t be asked about a matter that was very much on the minds of the nation’s Founders: the power of banks. The establishment of two consecutive central banks of the United States (the second of these a short walk from the debate venue) was opposed by Presidents Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson because they didn’t want the financial sector to acquire that much clout. When a third central bank, the Federal Reserve, was finally created during the Progressive era, it was in reaction to the excessive power of the financier J.P. Morgan, the only party able to rescue the economy from the Panic of 1907. In March 1913, John Pierpont Morgan went to his reward, and eight months later, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act into law.

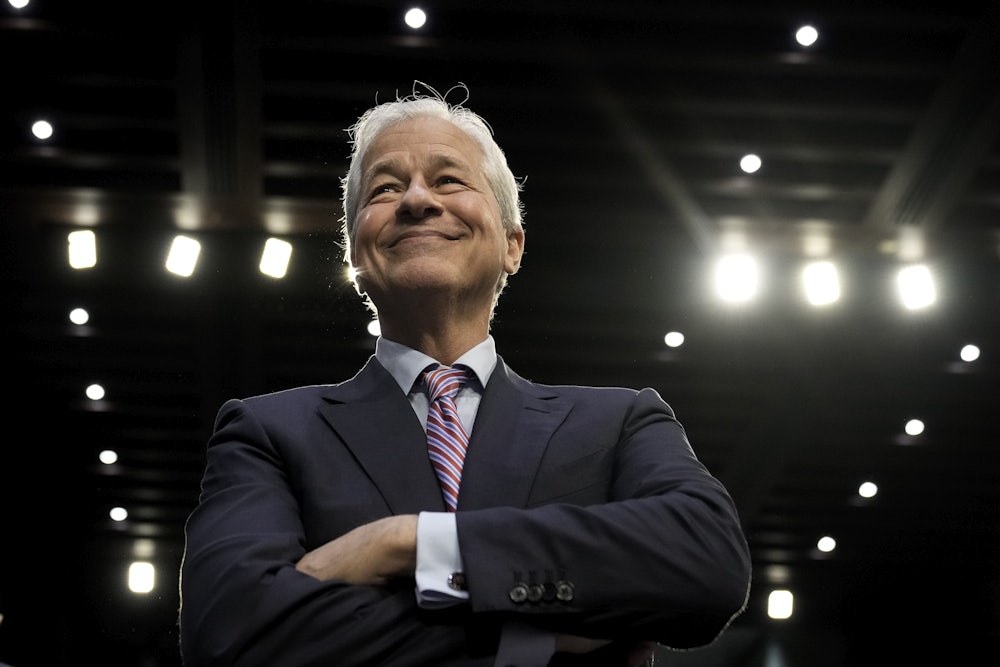

One hundred and eleven years later, it can sometimes be difficult to tell who’s in charge of the economy—the Federal Reserve or J.P. Morgan. No longer among us in corporeal form, the rosacea-scarred titan lives on as J.P. Morgan Chase, the richest bank in the United States and the fifth-largest in the world, with $3.9 trillion in assets. (Places one through four are held by Chinese banks.) J.P. Morgan’s chief executive, Jamie Dimon, enjoys a level of influence approaching that of his bank’s purple-nosed founder. So when the Federal Reserve last year proposed imposing significant new capital requirements on the country’s largest banks to bring the U.S. into compliance with an international agreement called Basel III, which was created in response to the financial crisis of 2007, Dimon said these new rules just wouldn’t do. On Tuesday, the Fed got the message and backed down.

The Fed’s 2023 proposed regulation came after the collapse of three medium-size banks—First Republic Bank, Silicon Valley Bank, and Signature Bank—called into serious question the wisdom of easing capital requirements, which Congress (and President Donald Trump) did in 2018 and the Fed (under a chairman appointed by Trump) did in 2019. Don’t confuse “medium-size” with “inexpensive.” The aforementioned three institutions accounted for, respectively, the second-, third-, and fourth-costliest bank failures in U.S. history.

The prospect of a large bank—such as J.P. Morgan, or Bank of America, or Citibank—failing is so catastrophic that the government simply doesn’t let it happen. (During the financial crisis, all three were bailed out to the tune of a combined $65 billion; they later paid it back.) Taxpayers like you and me have a strong interest against bank consolidation, to keep too-big-to-fail banks from getting even bigger and therefore even more expensive when we have to bail them out. But bank crises always lead to more consolidation. J.P. Morgan, for example—at the urging of bank regulators—purchased First Republic after the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation seized it.

All right then, you say. Let’s have fewer bank crises! That was the idea behind the recent Fed rule, which proposed increasing by 20 percent the reserves that large banks (i.e., those with more than $250 billion in assets) were required to hold against potential losses. After a campaign led by Dimon, the Fed scaled that back to a 9 percent increase in capital reserves. For good measure, the Fed also scaled back assorted requirements for midsize banks.

How did Dimon do it? According to The Wall Street Journal, he met in Washington with chief executives from the other too-big-to-fail banks and advised them to bypass Michael Barr, the Fed’s vice chair for banking supervision, and go straight to Fed Chair Jerome Powell. By last May they’d met with Powell more than a dozen times, with Dimon talking to Powell four times in person or by phone. In a pitiful attempt to shore up Barr’s wounded dignity, the Fed released calendars demonstrating that Barr too met with chief executives from the big banks—15 times!—and, er, twice with Dimon. Announcing the scaled-back rule today, Barr said, “Life gives you ample opportunity to learn and relearn the lesson of humility.” Ouch.

Dimon’s tactic was to argue that inflation—Powell’s foremost worry during the past three years—would get worse if the rule took effect, because banks would have to raise the cost of borrowing to pay for the increase in capital reserves. Mortgages and small-business loans would be smaller. Pensions and college funds would produce lower returns. The price of a soda would increase. But as the nonprofit Americans for Financial Reform noted in a comment on the rule, “Banks could very easily raise their current capital levels by simply retaining more earnings, which are plentiful right now, instead of buying back shares or paying dividends.”

That will never happen, because all of corporate America is hooked on stock buybacks (which the Securities and Exchange Commission, before the Reagan administration, judged an illegal form of stock manipulation) as a sort of burnt offering to Wall Street. The financial deregulation that began four decades ago left pretty much the whole economy dancing to the bankers’ tune, at the expense of workers and customers. It’s true even of the banks themselves. There seems, at the moment, no way to rein in the outrageous degree of power that Dimon and his ilk have accumulated. It’s worse under Republicans, but it’s pretty bad under Democrats too. That explains why neither Trump nor Harris will be in any hurry to comment on this latest outrage—and why they probably won’t even be asked to.