This past weekend, California’s financial regulator seized the midsize First Republic Bank (assets: $229.1 billion) and turned it over to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. The FDIC, in turn, conducted a hasty auction and sold the bank to J.P. Morgan Chase (assets: $3.7 trillion). As Liam Neeson observes in Star Wars Episode One: The Phantom Menace, “There’s always a bigger fish.” Between 2000 and 2020, the number of banks operating in the United States dwindled from 6,326 to 3,985 as the bigger fish swallowed littler ones.

The bigger-fish analogy applies also to bank failures. Just one month ago, the midsize Silicon Valley Bank (assets: $209 billion) was the second-largest bank failure in U.S. history. Now First Republic is the second-largest, after Washington Mutual in 2008 (assets: $307 billion).

Or perhaps we should think in terms of boats. A bank that fails resembles, in many ways, an oceangoing vessel that sinks to the bottom of the sea. Depositors at First Republic will suffer no harm, just as depositors suffered no harm in March when the FDIC seized Silicon Valley Bank and the midsize Signature Bank (assets: $118 billion). (The latter, at the time the third-biggest bank failure in U.S. history, is now the fourth-biggest.) Still, shareholders in First Republic were wiped out completely, just as they were by the two earlier bank failures. Over the past four months, First Republic lost 97 percent of its market value, or $21 billion, as it tottered toward bankruptcy. The remaining $650 million now resides in Davy Jones’s locker.

The captain and his top crew are supposed to go down with a sinking ship. When, as in Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim, they do not, the result is ostracism, disgrace, and loss of livelihood. “Hang it, we must preserve professional decency,” says one character of the Patna, on which Jim was first mate.

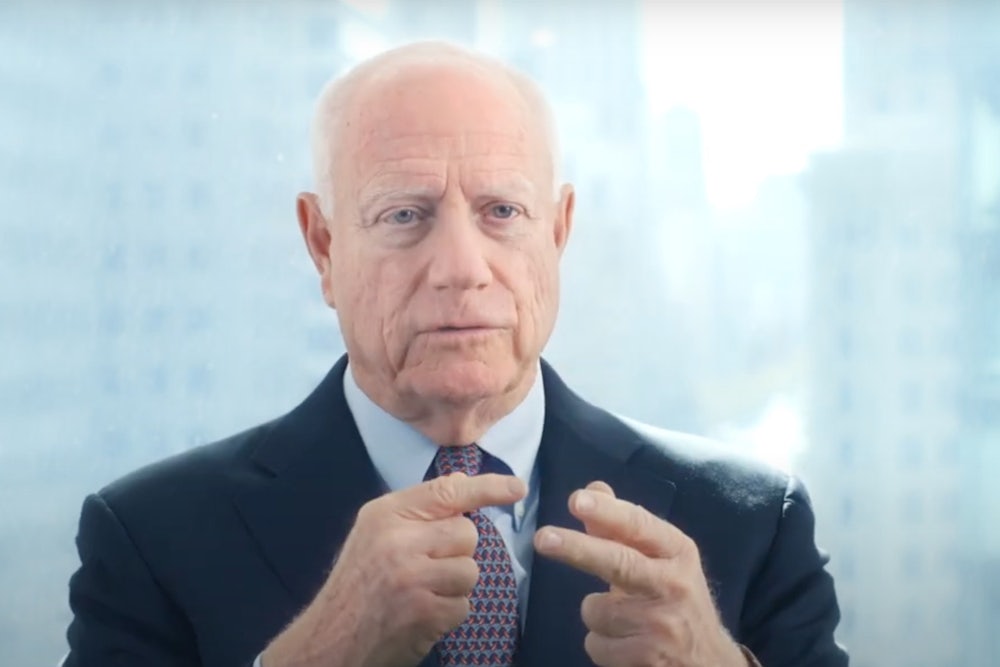

Nobody at First Republic appears to have read Lord Jim (or seen the 1965 movie with Peter O’Toole). I deduce this because in mid-March, The Wall Street Journal reported that James Herbert, First Republic’s founder and executive chairman, had sold $4.5 million worth of shares since the start of the year. Chief executive Michael J. Roffler, private wealth management president Robert L. Thornton, and chief credit officer David B. Lichtman sold a combined $7 million worth of shares during the same period. In November and December, Lichtman and his spouse sold an additional $2.5 million, and in November Roffler sold an additional $1.3 million. Thornton’s sell-off, on January 18, represented 73 percent of his outstanding shares.

There was nothing extraordinary about this behavior; executives at Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank did the same as their respective Patnas took on water. Greg Becker, financial chief executive of Silicon Valley Bank, sold $2.3 million in shares the week before the government seized his bank, and Daniel Beck, Silicon Valley’s chief financial officer, sold $575,000, or about one-third of his shares. Insiders at Signature Bank sold off more than $100 million in shares after the bank went long on crypto, a bet that of course went sour.

Last Saturday, the economist Dean Baker wrote on Twitter that First Republic’s Herbert got paid $9.2 million last year and Silicon Valley Bank’s Becker was paid $9.9 million. “Is that the market price for someone to send your bank into bankruptcy?” Baker quipped. “I’m pretty confident that I can send a bank into bankruptcy, and I would be willing to do it for half the pay.”

Baker got his numbers wrong—but the corrected numbers strengthen his point. We don’t know what Herbert got paid in 2022, because those figures aren’t yet public. But in 2021, Herbert’s last year as chief executive, he got paid not $9.2 million but $17.8 million. Becker got paid $13.7 million in 2021 and just a bit less, $13.5 million, in 2022. To complete Baker’s survey of what you get paid to run a bank into the ground, Signature bank chief executive Joseph DePaolo received $8.7 million last year.

Now that these three banks have gone belly-up, do the executives have to give any of their incentive-based pay back? They do not. In March, First Republic said in an FDIC filing on March 22 that all executive bonuses “would be reduced to zero for the full year 2023,” that the banks would also forgo company vesting “of all performance-based incentives” for 2023, and that Herbert would waive his salary for the year (though only that portion covering March 12 and after). This act of penitence rings a bit hollow now that we know those same top executives spent the previous five months selling off stock worth in excess of $15 million.

There’s a provision in the Dodd-Frank financial reform law that’s supposed to deal with such grotesqueries. Section 956 directed bank regulators to look at whether “an executive officer, employee, director, or principal shareholder” of a bank is rewarded by a compensation structure that “encourages inappropriate risks.” If so, that bank is in violation of the law. Section 956 is of course especially relevant when a bank fails.

The regulation enforcing Section 956 was supposed to be in place by May 2011. A dozen years later, there’s still no rule in sight. It isn’t even on the semi-annual regulatory agenda, which lists all rules that various federal agencies will be working on in the coming months. The Obama administration took a couple of stabs at a proposed rule in 2011 and 2016, but it was still fiddling with the details when Donald Trump assumed office, and the rule was put on the back burner. Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Gary Gensler promised to revive it, but so far he hasn’t.

That vexes Senator Chris Van Hollen, a Maryland Democrat, and Representative Nydia Velazquez, a New York Democrat, given that Becker especially seems to have been rewarded financially for putting his bank at financial risk. So last week they wrote Gensler and other financial regulators and proposed a rule enforcing Section 956 that would require all incentive-based compensation for bank executives to be deferred “for a period longer than a financial institution’s typical credit cycle,” which is to say several years. If the bank thrives, they get their incentive pay. If it doesn’t, the bank claws the money back.

The FDIC released a report Monday calling on Congress to increase its deposit guarantee from $250,000 to $500,000 to $1 million and perhaps more. Something like that seems likely to pass. But Congress’s price for increasing federal insurance extended to large depositors ought to be that the SEC moves on Section 956. The clawback proposed by Van Hollen and Velazquez is an excellent place for discussion to begin.