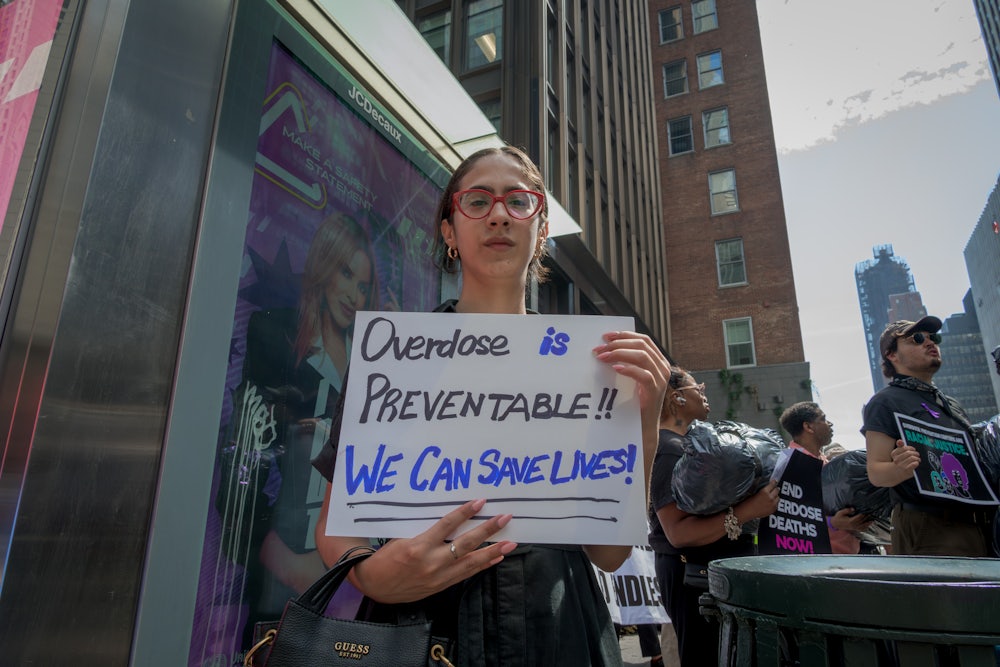

Years after it was declared a public health emergency, the overdose crisis continues to impact the nation in profoundly tragic ways. In 2023, more than 107,000 people in the United States died of a drug-related overdose. For people aged 18–45, the leading cause of death may be fentanyl-related drug overdose; each week, dozens of teens die of an overdose across the country. Overdose death rates have increased for Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Native Americans. Families from rural West Virginia to the streets of the Bronx have something sorrowful in common: They all find themselves grieving a loved one.

But if you’ve been paying attention to this year’s presidential campaign, you wouldn’t really think it’s that big an issue. The Republican Party platform has no section about tackling the overdose crisis, while the Democratic Party offers three small paragraphs that address the Biden administration’s work in expanding treatment—and increasing the use of naloxone—while promising this work will continue under a Harris administration.

And while you may not hear about overdose deaths themselves, both parties have extensively referenced the drug that is causing them—fentanyl. The Republican Party platform makes mention of the drug, and the Democrats reference it 16 times in their own platform. But instead of tying the synthetic opioid to the ongoing public health crisis, politicians have cynically entangled “fentanyl” in an entirely different issue: It’s being used to hype up the ongoing political culture war involving border security and immigration.

In multiple ads touting her border security chops, Kamala Harris promises that as president she will crack down on fentanyl, including by investing in fentanyl detection technology to block it from entering the country. The Republicans, meanwhile, directly implicate migrants, with Donald Trump frequently saying that migrants are responsible for an increase in fentanyl overdoses. All of this has damaging impacts on what people believe about asylum-seekers—a 2022 poll, for instance, found that many Americans, especially Republicans, believe that migrants are smuggling fentanyl across the U.S. border. This, of course, is a flat-out lie: Most fentanyl enters the country through ports of entry and is carried by U.S. citizens.

Predominately talking about overdoses as a border security issue not only falsely ties people seeking asylum to overdose deaths but also overshadows real solutions to this crisis, while inhibiting their potential effectiveness. Fentanyl is a dangerous drug, but it is talked about as if it was a “weapon of mass destruction” and treated like a threat to national security—like anthrax, rather than something that contributes to overdoses and substance use disorders. What this misses is how fentanyl impacts the drug supply and who uses drugs in the United States.

On the one hand, fentanyl is found in pressed pills and can sometimes be mixed into drugs like cocaine (usually inadvertently). For people who have no prior exposure to fentanyl, say a teenager buying pills, such a dose can be deadly. There are also people who regularly use fentanyl (heroin is almost impossible to get in the U.S. nowadays) and are used to the dosages. If they don’t use fentanyl, they can go into withdrawal. At the same time, the drug supply is constantly changing, and new, more potent drugs can emerge—putting regular users at risk of overdosing. This is a complex and multifaceted problem, and it affects different people in a range of ways.

Instead of flattening this knotty issue into the discourse about immigration, politicians—especially Vice President Harris—could pick a more fruitful path by engaging with the current, cutting-edge solutions that are on offer.

For instance, there are still barriers to access to medications for opioid use disorder, such as methadone and buprenorphine. While the pandemic did precipitate some changes—buprenorphine and methadone can be prescribed through telehealth, and people using methadone can now get a 30-day take-home supply—medication remains inaccessible to many of the people who need it most. One such issue that evades our one-size-fits-all approach to the crisis is that federal regulations still require people to get methadone from an opioid treatment facility, which can force people to travel long distances to get their dosages.

Currently, there is a bipartisan bill—the Modernizing Opioid Treatment Access Act—sponsored by Senators Rand Paul and Ed Markey, which aims to allow people to get their dosage from a pharmacy. This is how other countries, such as France, dole out doses of lifesaving opioid medication. Another issue presented by the changing drug supply is that more potent forms of fentanyl mean that current treatment regimens may not be sufficient to prevent withdrawal. These dosages are regulated and controlled by the federal government, and there may be a need to increase these limits to better assist people in treatment.

Naturally, not everyone is ready and willing to stop using drugs—but these people don’t deserve to die. Overdose prevention centers are a solution being explored in places like New York, Vermont, Minnesota, and Rhode Island. These are facilities where people can bring pre-obtained substances to use under the supervision of trained staff who can intervene in the event of an overdose. These sites are not just effective at preventing overdoses, they offer a slew of other health and community benefits.

Instead of engaging with these measures, both Republicans and Democrats are instead choosing a failed law-and-order approach that aims to control the supply of drugs rather than addressing the root causes behind the demand. To an outside observer, it might seem sensible to take this approach—just stop the fentanyl from coming in, and people will stop overdosing, right?

The problem is that this approach, in practice, is a failure: It hasn’t proven to be effective and, as it stands, may make matters considerably worse. For instance, when Donald Trump secured an agreement with the Chinese government in 2019 to ban fentanyl, it did result in a drop in fentanyl shipments from China. Sadly, this did not solve the problem—fentanyl continued to enter the country, produced via precursors; since then, the animal tranquilizer xylazine and other drugs have been emerging in the drug supply.

It is, in other words, a game of Whac-a-Mole—hit the supply in one place, and a more deadly variant may emerge somewhere else.

This can even be seen at a local level with drug seizures. One study that looked at counties nationally found that counties with a high amount of fentanyl seizures had higher overdose mortality than counties that didn’t have as many seizures. Another study found a similar result in Indianapolis, where there was an increase in overdoses and related deaths days and weeks after a seizure of drugs. This is an underappreciated consequence of seizures: When someone’s usual supply of drugs is interrupted, they will go to dealers and supplies they are unfamiliar with, which means potentially encountering doses of greater lethality.

In line with this law-and-order push that focuses on tackling the supply, harsh penalties for fentanyl possession are being pushed across the country and people are being charged with homicide for dealing fentanyl when it results in an overdose. Never mind the fact that those who deal drugs are often those who use drugs and that one of the biggest risks for overdose is recent incarceration. These policies further push people in the shadows at a time when they may need help.

This is happening simultaneously with a massive push from cities and states, like California, to use the Supreme Court’s recent ruling in the Grants Pass case to evict homeless people from encampments. Public drug use is an oft-cited rationale for clearing people from the streets, but people who are without housing are often at high risk of overdosing and encampment sweeps only increase this risk by cutting people off from communities and services that they depend on.

It need not be this way. Instead of scapegoating migrants and continuing to burn money on a supply-side, law enforcement strategy, politicians can choose to engage with the overdose crisis as the public health issue it is. They can support evidence-based, people-centered policies that focus on treatment and harm reduction—and which don’t inadvertently kill the people they are ostensibly trying to save. They can address a key risk factor for overdosing—being unhoused—by expanding housing, which evidence suggests can reduce overdose risk. They can expand social welfare programs like unemployment insurance, which can reduce the impact that job loss has on overdose risk. Such policies should be viewed as preventative, as much as, if not more than, drug-related education.

These policies can all be framed as a muscular effort to put drug cartels out of business by denying them a market in the U.S. by addressing the root causes of the crisis they are exploiting. While the overdose crisis is not going to be solved overnight and America’s relationship with substances will require decades of work—inseparable from other struggles for economic and social justice—politicians can choose to start to stem the bleeding now by ending their own dependence on policies that may sound tough but have failed on every level to end this crisis.