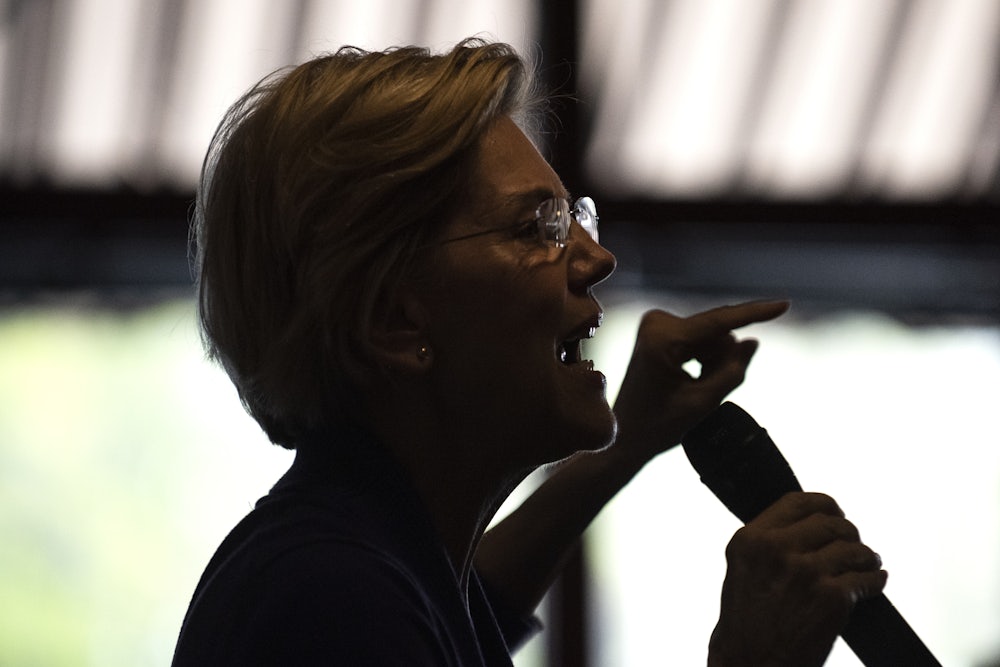

Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren is causing a stir in Trump country. In a rural West Virginia town with a population of 400, Warren spoke to a crowd of 150—many decked out in MAGA paraphernalia—about the opioid crisis. “Anyone here know someone who’s been caught in the grips of addiction?” Warren asked. Nearly every hand shot up.

“I have a plan for that” has become an unofficial motto for Warren’s idea-heavy candidacy. The policy pacesetter of the Democratic primary, Warren has already released detailed plans to break-up Big Tech, cancel student loan debt, and provide universal childcare via a tax on multimillionaires. Warren’s latest proposal, her thirteenth, would devote $100 billion over ten years to fighting the opioid crisis.

On Friday and Saturday last week, Warren traveled through rural areas (the small towns of Kermit, West Virginia and Chillicothe, Ohio) and big cities (Columbus and Cincinnati, Ohio) that have been hit hard by opioid and narcotic abuse. There she discussed her plan, which is based in part on the government’s response to HIV/AIDS in 1990, and would put funding toward improving addiction treatment and other efforts aimed at reducing overdose deaths. “There’s a tremendous amount to like here,” Bradley Stein, director of RAND’s Opioid Policy Center, told Yahoo. “The magnitude of the investment really matches the needs of the crisis,” he said, noting that previous expenditures were “a drop in the bucket.”

Warren’s plan has won plaudits from rural voters, who many in the party believe Democrats have to win back to defeat Donald Trump. But her opioid policy is a relative rarity in the Democratic field. The majority of the now two-dozen candidates in the race may have embraced some version of Medicare for All, but only Warren and Amy Klobuchar (who has a less specific $100 billion plan to fight drug and alcohol dependence) have made addiction a focal point of their campaigns. This is a mistake. Prescription drug addiction—and the illicit narcotic abuse to which it can often lead—is a serious issue for voters across the country.

It’s also, as Warren’s plan makes clear, a corruption issue: Several pharmaceutical companies have gotten rich off of this problem. If Democrats are actually serious about taking on both corruption and health care reform—arguably the two most dominant issues in the upcoming election—Warren’s message is a good place to start.

Tackling the opioid crisis was important, if cynical, part of Donald Trump’s 2016 political playbook, particularly in the hard-hit state of New Hampshire. Through Trump’s jaundiced eyes, opioid abuse is, as most things are, an outgrowth of illegal immigration. “Not only will a wall keep out the dangerous drug dealers, it will also keep out ... the heroin poisoning our youth,” Trump told New Hampshire voters in October of 2016. “We’re going to set up programs,” he promised. “We’re going to try everything we can to get them unaddicted.”

Trump ultimately won the areas most affected by opioids in 2016 and, according to a study from Penn State’s Shannon Monnat, “outperformed the previous Republican candidate Mitt Romney the most in counties with the highest drug, alcohol, and suicide mortality rates.” But in office, Trump has done little to fight prescription drug abuse.

“We will never stop until our job is done, and then maybe we’ll have to find something new,” the president told a gathering of drug addiction professionals in late-April. “And I hope that’s going to be soon.” But his administration has done little of substance. A public health emergency was declared in 2017, but no plan was offered for fighting the opioid crisis and no additional money was allocated to federal agencies. A commission was created in 2018 to study the epidemic and make recommendations for how best to fight it, but very little information from that effort has been made public, prompting Warren and Washington Senator Patty Murray to demand an investigation.

In March of last year, the administration released a skeletal plan that focused almost entirely on harsher sentences for dealers, including a controversial plan to recommend the death penalty with greater frequency for drug traffickers. “These are terrible people, and we have to get tough on those people, because we can have all the blue ribbon committees we want, but if we don’t get tough on the drug dealers, we’re wasting our time,” Trump said, seemingly discounting his own opioid commission.

The Trump administration’s lack of action is an opportunity for Democrats, something Warren, in particular, recognizes. Health care was, by many counts, the most important issue in the 2018 midterm elections, and it is likely to play a pivotal role in 2020. Warren’s plan to combat the opioid crisis is a microcosm of her larger health care reform agenda. It would give $4 billion to states, territories, and tribal governments, with $2.7 billion reserved for the areas most severely affected by opioid addiction. Nearly $2 billion more is reserved for training and research. Finally, $1.1 billion would be directed to groups—both public and private nonprofit—that are focused on ending the crisis, with another $500 million given to expanding access to the overdose antidote naloxone. It’s the kind of detailed plan for fighting the opioid crisis that Trump has promised for years but never delivered.

But the health crisis is only one part of the problem. “We got a second problem in this country and it’s greed,” Warren told voters in West Virginia last week. “People didn’t get addicted all on their own, they got a lot of corporate help. They got a lot of help from corporations that made big money off getting people addicted and keeping them addicted.” This is where Warren’s message becomes even more resonant and where it dovetails with the rest of her extensive agenda for repairing a broken country.

Should a Democrat win in 2020, health care reform will require much more than campaign promises and focus-group-tested buzzwords. It will require identifying and confronting those corporations and groups with a vested interest in propping up a corrupt system. And, politically speaking, addressing the opioid crisis might be one of the easiest avenues for Democrats to do this. (Observe the recent turn against the Sackler family, whose Perdue Pharma aggressively pushed oxycontin—perhaps a sign of a general distaste for the pharmaceutical companies that created, exacerbated, and profited from the opioid problem.)

Having spent much of the past two years casting about for a message that will resonate in what, for lack of a better label, has been designated “Trump country,” most of the presidential field has surprisingly avoided speaking to the opioid crisis—or to Trump’s failure to do anything of substance about it. Warren’s proposal demonstrates that she recognizes the significance of this issue. After her reception in West Virginia and Ohio, maybe other Democrats will, too.