We hear it everywhere in Democratic circles: an acceptance of defeat. “We’ve all resigned ourselves to a second Trump presidency,” a senior House Democrat told Axios a few days ago.

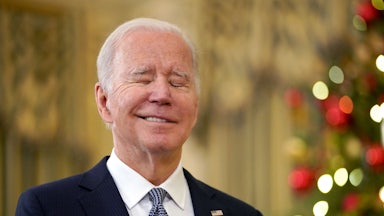

It would be shocking if it weren’t already obvious that they have given up. Even President Joe Biden himself suggested he’d be happy with the election results knowing that he “did his best,” perhaps a commendable sentiment for a Little League player but one that fails spectacularly to meet the current political moment. It seems the attempt on Trump’s life last weekend gave Democrats the excuse they needed both to stop lobbying Biden to drop out—a move that could help electoral fortunes up and down the ticket—and to stop campaigning altogether.

But four years is too long for Democrats to cede power. Some of these Democratic leaders no doubt assume that if the Trump-Vance ticket wins, the ensuing years will be so disastrous that the Democrats will win easily in 2028. But even if that were true, the logic ignores the fact that the climate crisis has a timeline. (And it’s not the only crisis that can’t be put on hold: Americans who need affordable housing, trans rights, and reproductive health care can’t wait four years, either.) It’s appallingly irresponsible to sell out the planet—and the human civilizations that call it home—for a game of electoral three-dimensional chess. We must treat Democratic defeatism as a kind of climate denial.

Scientists all over the world agree that we are running out of time to reverse or prevent the most serious consequences of climate change. Biden—despite inexcusably continuing to approve fossil fuel projects—made some progress on climate, investing in renewable energy and mitigation, and regulating pollution of all kinds. Any other Democrat, despite likely having the same kind of relationship with industry that hampered Biden, would continue to do the same. Every bit of policy action on climate, even when it’s not enough, saves lives and species and potentially makes our world more livable.

Trump, by contrast, has called climate change a “hoax” and dismissed the threat of rising sea levels. If anything, his second term might be worse than his first, given how the right has grown more radically opposed to climate action. He constantly spreads misinformation on the topic, saying that wind turbines cause cancer, are “driving whales crazy,” and spew “tremendous fumes,” none of which has even a grain of truth. And he already intends to roll back regulations and allow even more oil and gas drilling, he assured fossil fuel executives and lobbyists at an April gathering at Mar-a-Lago, urging them to give his campaign a billion dollars.

The broader conservative agenda is even more loopy than Trump’s fantasies about wind cancer. Project 2025, a Heritage Foundation–led document outlining a policy platform for day one of the next Trump presidency, calls for the elimination of offices within the Energy Department that oversee climate, renewable energy, and climate technology; opening up even more of the Arctic for drilling; reducing protections for endangered species; putting key Environmental Protection Agency functions in the hands of political appointees rather than career civil servants; eliminating the civil and criminal law enforcement functions at the Office of Water; and generally ravaging an invaluable regulatory infrastructure to which most people pay no attention but that they would sorely miss if it were gone.

Sure, the polls don’t look good for Biden, and Trump is having a moment—enhanced, according to the macabre rules of American politics, by surviving a startling assassination attempt. But what Democratic defeatists overlook, besides their moral obligation to fight, is that, again: Biden doesn’t have to be the candidate.

There is still time to step down and let Kamala Harris be the candidate, or embrace the excitement and uncertainty of an open convention, both approaches with different merits. Even if Biden remains the nominee (God help us) there is more to a campaign than polling. A campaign typically involves, well, campaigning, yet the Democrats have paused all that out of a bizarre sensitivity to Trump’s shooting. There is absolutely no evidence so far that the shooter was motivated by leftist ideology—despite the right’s baseless speculation. So what are Democrats thinking?

Climate voters know that Trump is bad news. If those people show up to vote, they could help save the election. Research from the Environmental Voter Project suggests that identifying infrequent voters for whom climate is a salient issue and turning them out to vote could be a powerful strategy to help Democrats win elections. Voters who prioritize the environment often belong to groups that don’t vote reliably, including the young and the poor. Spending energy and resources on turnout, then, could be more productive than simply taking gloomy prognostications at face value.

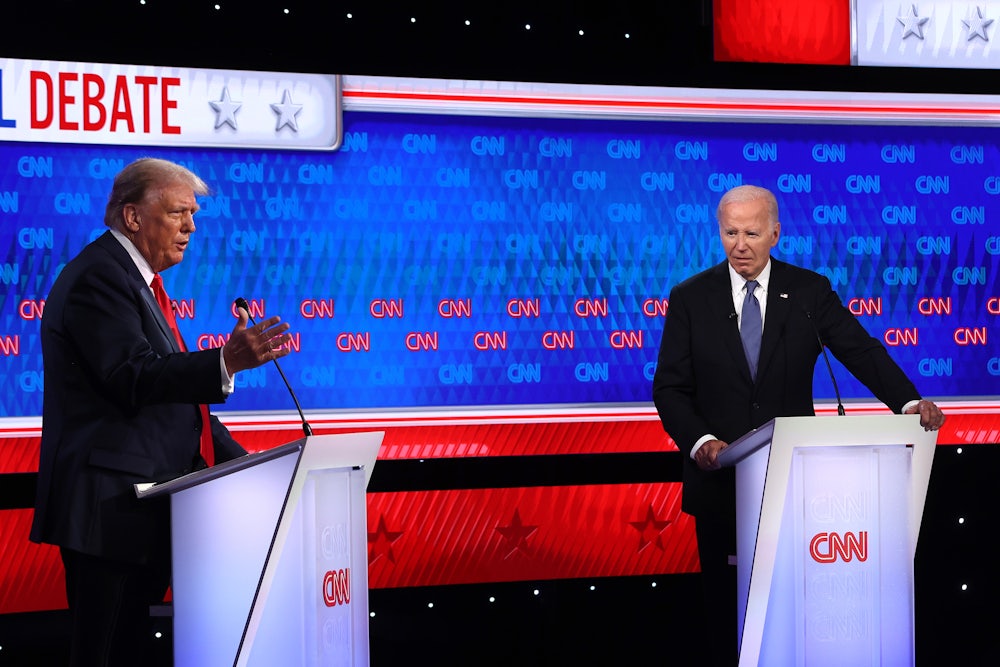

If Trump were losing in the polls—and we still might see that come to pass—he wouldn’t be giving up. Trump was campaigning the second after his assault, posing with his fist up. This week, Democrats are not even running TV ads or offering a counter-message to the Republican National Convention, an unprecedented abdication of political duty.

In a campaign, people can be persuaded. You can knock on doors, call them, send postcards, and remind them to get out and vote. Sure, Trump is polling well, but it is only July. The pervasive sense that the election is practically over is unwarranted; we have time to turn this around. But all the science agrees on how much time we should permit ourselves before seriously addressing the climate crisis: zero.