Annie Baker’s plays present characters who, if not miserable, are not far off, in circumstances to which they would mostly rather not be confined, but are. For another “not,” one might add that her drama is not explicitly dramatic, which is in fact a virtue of the hyperrealistic style that makes her one of the greatest playwrights working in American theater today. Her oeuvre can be read as an answer to the question posed by Nicolas Cage’s defeated screenwriter, Charlie Kaufman, in Spike Jonze’s Adaptation (2002), to Brian Cox’s “story” guru Robert McKee: “What if a writer is attempting to create a story where nothing much happens, where people don’t change, they don’t have any epiphanies, they struggle, and are frustrated, and nothing is resolved, more of a reflection of the real world?”

A dramatist no lesser than Chekhov created many such scenarios, and so has Baker, whose mood likewise spans the tragicomic spectrum. Like Uncle Vanya, which Baker adapted for Soho Rep in 2013, her film debut, Janet Planet, is set in the summer on a country estate; visitors drop in and overstay their welcomes; confessions lead to uncertain futures. Though Amherst, Massachusetts, in 1991 is no Imperial Russia, the globular house where Janet (Julianne Nicholson) practices acupuncture and lives with her 11-year-old daughter, Lacy (Zoe Ziegler), accommodates a metaphor for the characters’ lives: remote, circular, comfortable but lonely. As Lacy braces herself to start another school year, Janet attempts to swear off men. Defying Kaufman, Baker’s characters do have epiphanies, but the ubiquity of therapeutic breakthroughs in everyday life is in this film the stuff of stasis, not change, suggesting that the frustration of our struggle derives from our unwillingness and inability to accept who we are.

This is the theater of Chekhov, Ibsen, and Beckett but also the cinema of Bergman, Ozu, Cassavetes, and Malle, all filmmakers Baker curated for a series at Lincoln Center this month to accompany the release of Janet Planet, and pioneers of what Baker calls, citing Robert Bresson’s Notes on the Cinematographer (1975), the “anti-theatrical argument.” The cinematic art, for Bresson, “is a writing with images in movement and with sounds”: Because film lacks the “material presence of living actors” and the “direct action of the audience on actors,” Bresson wrote, it is necessarily a “bastard theater.” The “truth of cinematography cannot be the truth of theater,” and so the filmmaker’s job is to “film where the images, like the words in a dictionary, have no power and value except through their position and relation.”

The idiosyncrasies of Baker’s playwriting can be credited in part to her counterintuitive application of Bresson’s principles to the theater: Many of her plays address the nature of spectacle, performance, fiction, and theatricality at the same time that they subvert and dispose of dramatic conventions. She stretches the limits of patience by means of pauses and silence in The Aliens (2010), seats the audience behind a movie screen in The Flick (2013), and probes the shared origins of storytelling and religion in The Antipodes (2017), a meta-play in the spirit of Luigi Pirandello about something that feels more significant than a TV writers’ room, but might not be.

Baker rarely strays far from her native New England, and the regional flavor of her language and reference points makes her a sort of Kelly Reichardt of western Mass. This is nowhere more true than in Janet Planet, in which observations on the nuances of rural blue-state New Agery are articulated in the native accent of a speaker gifted with the irony of distance and cursed by the narrative impulse of autobiographical self-reflection. But in the transition to a new medium, Baker evades the trap of “filmed theater” that Bresson’s contemporary André Bazin warned against. Instead, by bringing her own experiments with duration, small talk, banality, and minutiae to the cinema, Baker makes, in Bresson’s words, “a voyage of discovery on an unknown planet,” adopting a camera to test the strength of her writing in a two-dimensional ecosystem of images and sound.

Whether Janet Planet is a nostalgic film is difficult to determine. Baker ekes amusement out of the outmoded set pieces and costuming of her youth in a way that invites comparison to fellow millennial (and sister-in-law) Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird (2017), set in post-9/11 Sacramento. But whereas Gerwig tracks a mother-daughter relationship through the end of adolescence, Baker constrains herself to a much uglier period of development: middle school. Janet Planet is not a period piece, insofar as the quasi-Buddhist pop psychology and fetishistic pursuit of “alternative” lifestyles that have plagued white liberals since the Johnson administration, at least, have never been more ubiquitous than they are now. Janet is a flower child beginning to wilt, a fact that Lacy, who sees the bad in everything, can’t help but notice.

Or almost everything. Lacy likes people who aren’t trying to sleep with her mom, practicing piano, and girls her age who deign to show her a modicum of kindness. The film opens at summer camp, where Lacy sneaks out of her cabin in the middle of the night. From a pay phone, she calls her mother collect: “Hi,” she says, “I’m gonna kill myself.” Janet arrives the next morning, but as Lacy prepares to depart, spinning a wishful yarn about her stepfather’s motorcycle accident for cover, another camper gifts her a troll doll, prompting Lacy to tell Janet, “I thought nobody liked me, but I was wrong.” “This is a bad pattern,” Mom responds. Wayne (Will Patton) looks to be the stepfather in question, but he and Janet are not married, and there he is, leaning against a car parked in a field. “I’m not going to kick him out just because you wanted to come home from camp,” is Janet’s answer to her daughter’s complaint, and as the car drives off to a cassette of Merle Haggard’s “Here Comes the Freedom Train,” the first act begins.

Anti-theatrical or not, Janet Planet draws attention to its formal structure, announcing each act with a title card named after a different interloper in Lacy’s summer at home. “Wayne” comes to an end after a migraine that he believes Janet “transferred” to him leads to his slamming a door in Lacy’s face and, at the girl’s recommendation, a break-up—but not before an idyllic day at the mall (an expertly scouted, period-specific fossil) with Wayne’s daughter, Sequoia (Edie Moon Kearns), who does not live with her father, as Lacy, naïvely or not, reminds him incessantly, obnoxiously prying for the reason why. “I’d like to be friends with her,” Lacy tells the couple over a mostly silent dinner on the deck, “I usually have a hard time making friends.” Later, once it is clear that her connection with Sequoia will remain short-lived, Lacy says, “You know what’s funny? Every moment of my life is like hell.” Janet replies, “I don’t like it when you say things like that,” but with the caveat, “I’m actually pretty unhappy too.”

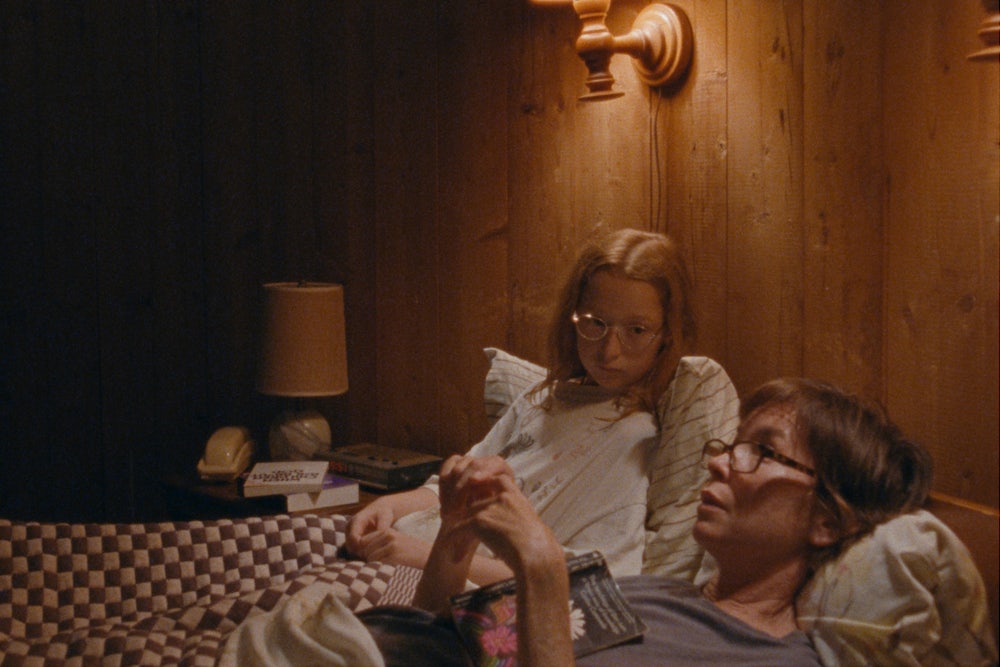

Like mother like daughter, though Lacy does not share Janet’s “terrible taste in men.” “Would you be disappointed if one day I dated a girl?” Lacy asks in the bed they share (another pet peeve of Wayne’s). “No, I wouldn’t be disappointed at all. I’d be very happy for you. I always wondered one day if you might turn out to be a lesbian. You have a forthrightness and a kind of aggressive quality … I wondered if it might be easier for you to be with a woman.”

This scene, the film’s most moving, comes toward the end of “Regina,” the second act, in which an estranged friend of Janet’s (Sophie Okonedo) seeks refuge from the commune where she has been living with a lover, Avi (Elias Koteas), the director of a local theatrical troupe and also, perhaps, a cult leader. The premature intimacy Lacy feels around Regina—a Black British actress, which must strike a young girl raised in such lily-white environs as exotic—serves to precipitate her coming out, just as a misguided attempt at psychedelic therapy wedges a rift between the two women, awakening Janet to the source of her distress. “My own liberation depends on my ability to put truth before my desire to be liked,” Janet repeats to herself on a walk through the woods, and as Lacy listens on, the mantra transforms: “self-image” replaces “liberation, “ability” becomes “willingness,” “liked” turns into “loved.” Meanwhile, Janet brokers a reconciliation between Regina, who has failed to pay rent, and Avi, the subject of the penultimate act, who courts Lacy’s mother with a bottle of red. A young man from the commune arrives to hurriedly gather Regina’s things, tearing a New Yorker cover from the alcove she used as a room, leaving a fragment taped to the wall as a memento of her abrupt entrance and exit from their lives.

As the summer comes to an end, Lacy feigns illness to avoid returning to school, and Janet feigns interest in Avi’s hillside recitation of Rilke’s “Fourth Elegy”: “Angel and puppet! Now at last there is a play!” Back at home, Lacy, stuffed with milk, antibiotics, and microwaved blintzes, stages a puppet show of her own, her dollhouse figurines decorated with hats repurposed from chocolate truffle wrappers and a stray earring pilfered from the kitchen floor. Suddenly, Avi disappears into thin air; Janet packs up her picnic basket, descends the hill, and eats a chicken wing from the privacy of the driver’s seat. This deus ex machina, a likely if implausible effect of Lacy’s bedroom ritual, shatters the film’s realist facade; the magic of theater alters the protagonists’ lives for good—but this is no metaphor, and Lacy is finally able to muster the courage to climb aboard the school bus, presumably not for the last time.

Was Avi a puppet? An angel? And who, then, are we? As Rilke wrote, “to contain death, / the whole of death, even before life has begun, / to hold it all so gently within oneself, / and not be angry: that is indescribable.” Alone at last, Janet discerns in her serial monogamy an irrational fear of the inevitable; for Lacy, who teases a smile in the final shot, sitting out a square dance lesson her mother does not bother convincing her to join, the possibility of morbidity without anger appears to bring peace, and Baker’s film concludes with resolution, if not exactly hope. With staid cinematography, Janet Planet embraces its status as a minor film, but its themes are major as could be, the ordinariness of plot and plainness of style undermined by the eccentricity of characters and universality of emotion. Whether Baker will make another film matters less than that she continues to write: Language is her medium, and if cinema is the mechanism that will allow her audience to grow, so be it. Few filmmakers understand “the terrible habit of theater,” as Bresson put it, well enough to call it into question.