Recently, I went to a screening for a documentary following four young Black girls attending a dance with their fathers in a local prison. I was struck in particular by a 5-year-old counting the days until her father is freed. I laughed and cried along with the audience as she quipped about her family and bragged about her schooling, playing the well-worn part of an innocent kid caught in a tragedy.

Then the film ended and there she was, sitting for a panel to discuss what we’d just seen. This version was reticent tween with butterfly twists, visibly working through the implications of her childhood broadcast at Sundance. She didn’t really know what was happening around her, she admitted, until she saw the film herself.

As she muttered her way through the discussion, I was surprised by just how surprised I was: I knew she would be there since the screening was organized around the girls’ attendance. But for nearly two hours I had been fed a character; the film had cast her as an avatar for a social issue. To quote Toni Morrison in The Origin of Others, “I immediately sentimentalized and appropriated her.” In reality, she’s just a girl dealing with trauma whose circumstances were caught, packaged, and distributed to the many eyes of strangers before she fully realized what had happened to her family.

American life today is largely digested through screens. If we’re not working through screens, we’re learning with them, socializing through them, entertaining ourselves with them, each new digital platform flattening our faces into images and compressing our interior lives into text. Each of these interactions carries a risk of making the other person on the screen—captured, digitized, packaged and sold—a little less human. Legacy Russell’s new book, Black Meme: A History of the Images That Make Us, interrogates America’s relationship with Black imagery, iconography, and symbolism—quite literally, at points, the Black face. Tracing a pattern from the 1915 propaganda film The Birth of a Nation to the media fallout from Breonna Taylor’s murder in 2020, Russell illustrates how American visual culture relies on Black culture while stripping the people at its center of their humanity.

What is a meme? There’s the colloquial definition: an out-of-context image or video, disseminated as a collective in-joke. These memes contribute to the effect that Russell describes in her book. But Russell is talking more broadly about the “meme,” defined simply as an image spread around with increasing variations, a “self-replicating chunk of information,” as linguist Kirby Conrod has explained.

A “dawning digital culture” has drawn heavily on memes, and accordingly it “has been driven by, shaped by, authored by, Blackness,” Russell argues. The “Black meme”—the sassy reaction GIF, the funny viral video, the body camera footage displaying a real-time murder—functions as “both a trope and a trap,” aiding in the ongoing dehumanization of Black people and co-optation of Black culture in a new social context.

Russell’s story begins, however, long before the first dial-up connection. The first Black meme she examines is the lynching postcard, the early twentieth-century practice of spreading grisly images of white families gathering around grills and picnics as Black bodies hung on trees. These cards didn’t just memorialize the event, she writes, but “became a viral advertisement for violence,” a “memetic transmission of social and corporeal death.”

She sees the same gruesome dynamic in the wake of Emmett Till’s murder in 1955: Black pain, white profit. While most know the story of Emmett Till, fewer are aware of the micro-economy that sprung up after Jet published its infamous casket photo. Till’s murderers, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, received $4,000 from an interview with Look magazine. The family of a white juror in the 1955 trial, which acquitted Till’s murderers, has since come to own the site where Till was accused of whistling at a white woman, aided with funding from the Mississippi state government, and in 2018 the family refused to sell the site for less than $4 million. Even as recently as 2017, white American artist Dana Schutz debuted an abstract painting of Till’s casket photo at the Whitney Biennial, to the chagrin of many Black artists and spectators.

Russell traces a pattern from Bloody Sunday in Selma, Alabama, in 1965 to Trayvon Martin’s murder in 2012. Violence inflicted on protesters marching across the Edmund Pettus Bridge created a national spectacle that “advanced and cultivated empathy across the nation,” Russell writes; yet it also served as a precursor to the “voyeurism and extractive violence of mass media,” as images of state violence waft through our social media feeds and can be shorn of context, made to mean whatever the person posting wants them to mean. This vulnerability is no more apparent than in the murder of Trayvon Martin, which sparked not just national protests against police violence but a sinister viral trend called “Trayvonning.” Viral Blackness objectifies its subject, rendering them an image, an item, a concept, or a joke. “Black life in precarity, a gross commodity for sale, sells cheap but travels fast,” Russell writes.

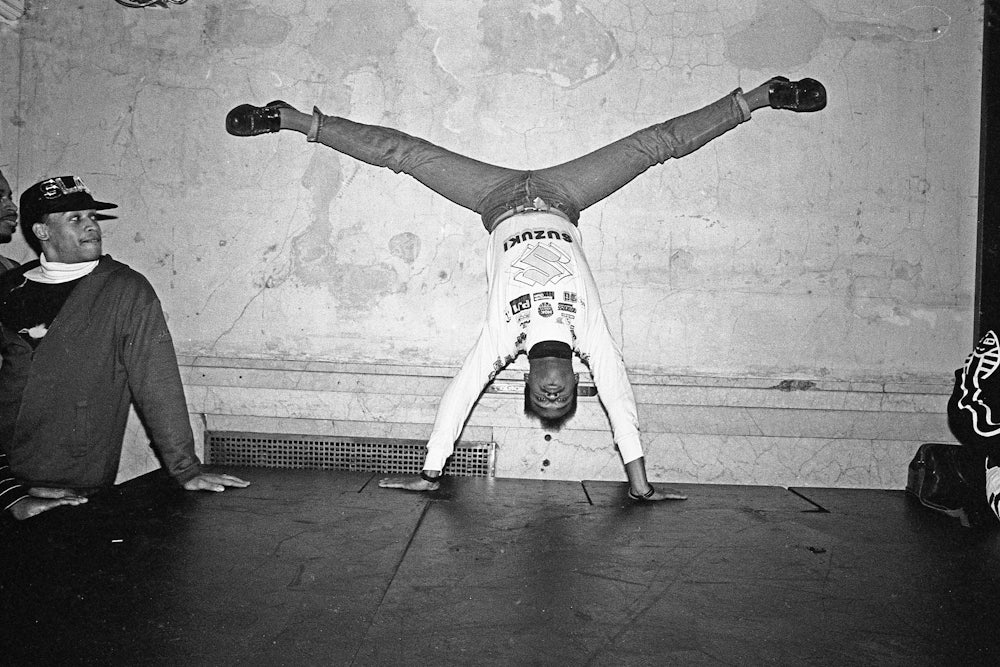

The exploitation of Blackness also plays out in culture. Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning immortalized the “ball culture” of 1980s New York, alongside several of its central characters. Ballroom culture was a social phenomenon propagated by queer communities. The performers walked in runway-style shows that blended fashion and dance, competing to give off “realness”—ballroom parlance for embodying “an impersonation of a racial or class norm,” Judith Butler wrote in their 1993 essay “Gender Is Burning” (which was also cited in Black Meme). These communities were a place for flourishing gender and creative expression; they also served as prototypical safe spaces for gay, lesbian, and trans people to escape domestic violence, economic precarity, and houselessness stemming from the rampant homophobia of the age.

Paris Is Burning brought queer Black and brown subcultures to the mainstream: Even today, middle school kids sporting Nicki Minaj avatars on Instagram trade in the colloquialisms that sprang up from its cultural aura (“reading,” “shade,” “queen” chief among them). But the performers featured in Paris were only paid $55,000, split 13 ways, while the film itself grossed $3.8 million across the country. One of the performers, Paris Dupree—a pioneer of “voguing”—filed an unsuccessful lawsuit for $40 million. The film wouldn’t have been possible without the distinctive performances of the Black artists at its center, yet they did not share substantially in the financial rewards. “The Black person, reduced to a Black body, reduced to a Black object, is distilled into its aura,” she writes, “and it is the aura of Blackness that lends material property its value.”

The concept of “dehumanization” has been in conversation with Blackness in America since the introduction of chattel slavery, but it appears in how we uplift Black people as well. In a chapter focused jointly on Anita Hill and Magic Johnson, Russell illustrates how hypervisibility threatened to treat them both, amid harrowing life circumstances, as abstractions for a larger cause. Hill’s testimony alleging that then–Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas sexually harassed her has frozen her in time: hair coiffed, dressed in a turquoise suit, standing with a hand raised to swear the oath. While Thomas still went on to sit on the high court, Hill became mythologized as an early archetype of the #MeToo movement, even reappearing at its peak with a depiction of her case starring Kerry Washington.

Just a month after Hill’s testimony, Magic Johnson announced his retirement from professional basketball due to an HIV diagnosis. “I think we only sometimes think only gay people can get it; it’s not going to happen to me,” Johnson said at a November 1991 press conference. “I am saying that it can happen to anybody, even me, Magic Johnson.” Johnson made a decision to speak up, but he was “quickly co-opted by the national theater of American politics, turning him from sports icon to mouthpiece and political symbol,” Russell writes. Soon enough, he was enlisted for the federal government’s National Commission on AIDS. But in September 1992, he quit, writing to President George H.W. Bush that he couldn’t sit idle while his administration ignored the plethora of noncelebrity Americans dying from the virus every day.

Black icons are “critical to the Black meme, a necessary elevation of the ordinary to the extraordinary,” Russell writes. “It is a quasi-spiritualism that transforms figures, flawed in their everyday humanity, into simultaneous saints and martyrs.”

The internet supercharged the dynamics of exploitation. One of the earliest online memes—the collective inside joke that travels across the web—was the “Dancing Baby” craze of 1996. The dancing baby was a 3D animated white baby, doing an Afro-Latin dance to the tune of “Hooked on a Feeling”—more specifically, the “Oogachaka” part originally written by reggae group the Twinkle Brothers. It was funny because it was unexpected; it was unexpected because it was Black.

People emailed the file to each other, used it as a screensaver, posted it in forums, and used it in web ads. The Dancing Baby made cameos on late-night TV, in music videos, and famously Ally McBeal, as the titular character’s hallucination. The web was still so new at the time that barely any other meme had proved so contagious. 3D animator Michael Girard, who created the Dancing Baby, has speculated that “it spread because the file was a GIF you could easily attach to emails, and the baby seemed carefree and optimistic,” he said. “But mostly, and kind of disturbingly, people enjoyed ridiculing it.”

Just pages later, Russell quotes artist and critic Aria Dean, who asked in her 2016 essay “Poor Meme, Rich Meme,” “Does a white meme admin have any business posting an image of a Black person?” Dean questions whether the myriad “meme” pages that have sprung up on Instagram are “laughing with us or at us.” Are they even “capable of laughing with us?” The cultural critic Lauren Michele Jackson coined the term “digital blackface” to convey how the use of viral Black imagery by white people as reaction GIFs or sources of comedy serve as a new kind of “minstrel performance.” When a white person “claps back” at another Twitter user with a GIF of Nene Leakes being sassy, or they emote through Rihanna’s smirks and smizes, they are playing up “enduring perceptions and stereotypes about black expression,” and reinforcing the association of “black people with excessive behaviors, regardless of the behavior at hand.”

Perhaps most startling is Russell’s examination of how Breonna Taylor’s image proliferated after her murder helped inspire calls for racial justice in 2020. Well-meaning magazine covers, yard signs, and infographics had the effect of diluting the memory of Taylor as a specific person, loved by people who’re still haunted by her absence today. “Is Taylor’s afterlife one that lives on as an ornamentalized totem?” Russell asks. “Is Blackness itself just a decorative art?”

It doesn’t have to be. Toni Morrison considered ways to fight back against dehumanization in her lectures, collected as The Origin of Others. Images and language, she notes, have the power to “help us pursue the human project—which is to remain human and to block the dehumanization and estrangement of others.” This recentering is what Russell proposes as a remedy: In order to address digital exploitation, she argues, we need to de- and reconstruct the conditions of digital culture, building “one predicated on new definitions of authorship.” She closes the book by offering a chant: “Reparations now! Free the Black meme!”