It is hard to get nine random Americans to agree with each other on abortion. It is even more difficult if those nine Americans happen to serve on the Supreme Court. But right-wing legal groups and lower court judges have now done the impossible: They got a unanimous ruling from the high court on Americans’ access to mifepristone, the most widely used abortion drug in the country.

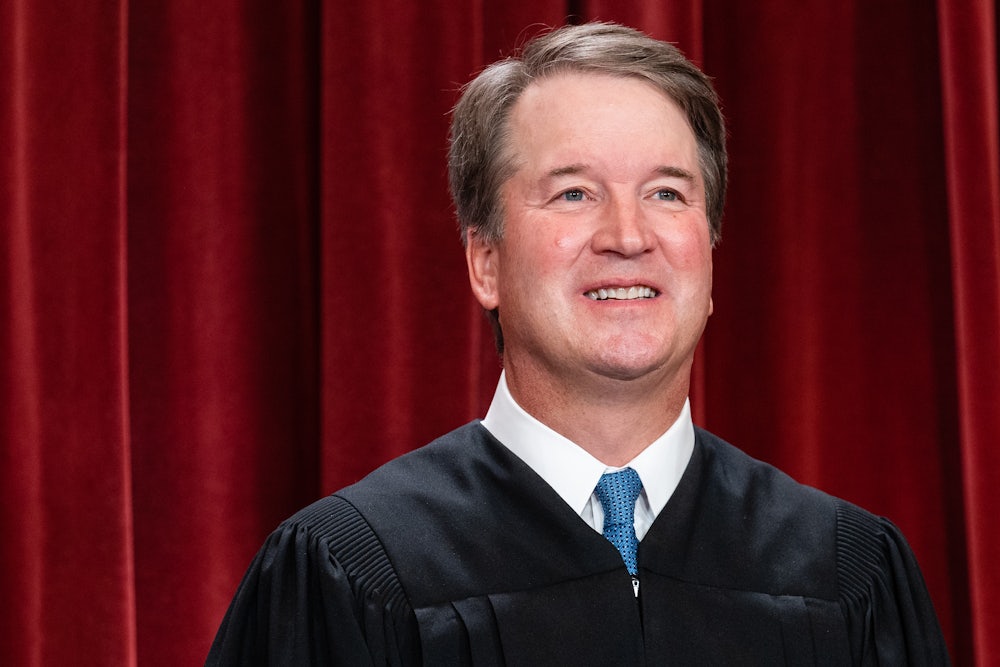

The only problem for them is that they lost. The Supreme Court rejected a two-year push to get the federal courts to overturn or limit the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of the most commonly used abortion drug in the country on Thursday. The 9–0 ruling preserves the status quo for most Americans. Justice Brett Kavanaugh, writing for the court in FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, said that the anti-abortion doctors who filed the lawsuit had no grounds to do so.

“The plaintiffs do not prescribe or use mifepristone,” he wrote. “And FDA is not requiring them to do or refrain from doing anything. Rather, the plaintiffs want FDA to make mifepristone more difficult for other doctors to prescribe and for pregnant women to obtain. Under Article III of the Constitution, a plaintiff’s desire to make a drug less available for others does not establish standing to sue.”

The ruling is a major defeat for the right-wing legal groups that organized the case. It is also another rebuke of the lower court judges who allowed it to proceed at all. The Supreme Court is increasingly unwilling to let the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals—and the district court judges in its jurisdiction—commandeer national policy on legally indefensible grounds.

This particular case began in the courtroom of Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, who happens to be the only federal judge assigned to the Amarillo division of the federal court in the Western District of Texas. That administrative quirk means that a plaintiff can effectively guarantee that their case will be heard by him if they file a lawsuit in Amarillo. This option is particularly attractive for conservative Christian legal groups since Kacsmaryk, who was appointed by Trump in 2019, formerly served as general counsel for one of them.

In 2022, the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, a pop-up coalition of anti-abortion doctors, sued the FDA to overturn the agency’s original approval of mifepristone 20 years earlier. They were represented by Alliance Defending Freedom, one of the country’s most prominent right-wing legal groups. The doctors argued that the FDA’s original approval of mifepristone in 2002 violated the Administrative Procedures Act, as did subsequent rule changes in 2016 and 2021 that made the drug easier to obtain.

Before addressing the merits of a lawsuit, courts must always decide whether the plaintiff or plaintiffs could bring it in the first place. The Constitution requires that courts hear only “cases and controversies,” meaning that they can’t hand down mere advisory opinions. In general terms, a plaintiff has to show that they suffered some sort of injury and that the court can actually remedy it.

“As Justice Scalia memorably said, Article III requires a plaintiff to first answer a basic question: ‘What’s it to you?’” Kavanaugh wrote. “For a plaintiff to get in the federal courthouse door and obtain a judicial determination of what the governing law is, the plaintiff cannot be a mere bystander, but instead must have a ‘personal stake’ in the dispute.”

The anti-abortion doctors argued that mifepristone had a risk of complications and adverse side effects. (This is true for any drug.) They do not prescribe it for conscience reasons. Nor did they claim to take it themselves as patients. Instead, they argued that they suffered legal injuries because other people took it and that their usage of it might have downstream effects on their own conscience rights if they treat those people as patients.

This is not how standing works, to put it mildly. The plaintiffs essentially argued that the FDA’s approval of mifepristone means that the doctors might encounter patients who took it, and that those patients might suffer some sort of complications from the drug, and that the doctors might have to violate their consciences by treating them. These are hypotheticals upon hypotheticals upon hypotheticals, creating a chain of causation that was too tenuous for the Supreme Court’s standards.

Kavanaugh noted that virtually every drug approved by the FDA had some risk of side effects and complications. Adopting the plaintiffs’ theory of standing would lead to chaos. “The plaintiffs’ loose approach to causation would also essentially allow any doctor or healthcare provider to challenge any FDA decision approving a new drug,” he wrote. “But doctors have never had standing to challenge FDA’s drug approvals simply on the theory that use of the drugs by others may cause more visits to doctors.”

He also noted that this approach would extend to other professions as well, with far-reaching consequences. “Firefighters could sue to object to relaxed building codes that increase fire risks,” he wrote. “Police officers could sue to challenge a government decision to legalize certain activities that are associated with increased crime. Teachers in border states could sue to challenge allegedly lax immigration policies that lead to overcrowded classrooms.” Kavanaugh concluded that this path “would seemingly not end until virtually every citizen had standing to challenge virtually every government action that they do not like.”

This is familiar ground for Kavanaugh. Twelve years ago, he heard a case brought by a vaccine-skeptic group while serving on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. The Alliance for Mercury-Free Vaccines had sued the FDA to stop the use of a mercury-based preservative that is found in most (but not all) vaccines. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other public health agencies say that the preservative poses no health risks to humans.

Writing for a three-judge panel, Kavanaugh rejected their argument on standing grounds because the group’s members were not actually affected by its presence in some vaccines. The group’s members had access to vaccines without the preservative, he wrote, and therefore would only be suing to deprive others of it. “Plaintiffs may, of course, advocate that the legislative and executive branches ban all thimerosal-preserved vaccines,” he wrote. “But because plaintiffs are suffering no cognizable injury as a result of FDA’s decision to allow thimerosal-preserved vaccines, their lawsuit is not a proper subject for the judiciary.”

What was obvious to Kavanaugh as a D.C. Circuit judge 12 years ago was more elusive for federal judges in Texas in this case. Kacsmaryk accepted the dubious standing arguments and struck down mifepristone’s original approval in 2002, threatening to take the drug off the market throughout the entire country. The Supreme Court stayed his order shortly thereafter while litigation continued.

On review, the Fifth Circuit allowed the drug’s original approval in 2002 to survive because the statutory time limits to challenge it had expired. But it adopted the plaintiffs’ standing theories to reverse more recent rule changes that made mifepristone more easily obtainable for most Americans. The three-judge panel held that the doctors’ hypothetical conscience injuries sufficed to provide standing. To reach that conclusion, the panel claimed that the Justice Department was “inconsistent” on whether federal conscience protections applied to the doctors.

Kavanaugh dispelled that illusion by relying upon Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar’s assurances during oral arguments. “As the Solicitor General succinctly and correctly stated, EMTALA does not ‘override an individual doctor’s conscience objections,’” he said, referring to the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act, the federal law governing emergency-room cases. “We agree with the Solicitor General’s representation that federal conscience protections provide ‘broad coverage’ and will ‘shield a doctor who doesn’t want to provide care in violation of those protections.’” This conclusion may have implications in another pending case on whether EMTALA supersedes Idaho’s near-total abortion ban.

When the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade two years ago, Kavanaugh emphasized in a concurring opinion that he meant to remove the federal courts from the abortion sphere as much as possible. “After today’s decision, the nine members of this court will no longer decide the basic legality of pre-viability abortion for all 330 million Americans,” he wrote. “That issue will be resolved by the people and their representatives in the democratic process in the states or Congress.” He cast the court’s ruling as a matter of representative democracy, with Roe representing its antithesis.

In this particular case, Kavanaugh stayed true to his word. As a parting blow, he rejected suggestions from some parties that surely someone must have standing to challenge mifepristone. “Even if no one would have standing,” he wrote, “this court has long rejected that kind of ‘if not us, who?’ argument as a basis for standing.” He concluded that “some issues may be left to the political and democratic processes.” This is a useful reminder for many Americans—and an essential one for the Fifth Circuit. The Supreme Court has had to devote a significant amount of its time and energy in recent years to fixing that court’s breezy approach to standing, which gets in the way of its desire to act as a junior-varsity SCOTUS.

Last year, the justices overturned a Fifth Circuit ruling against President Joe Biden’s student-loan debt-relief order because the two plaintiffs who received relief were obviously not injured by it. Two years ago, they saved the Indian Child Welfare Act from the Fifth Circuit’s mangling of it by holding that the challengers had effectively sought an unenforceable advisory ruling to demolish the law. The court quashed an attempt by Texas and Louisiana to commandeer federal immigration policy after a federal judge in Texas sided with the states and the Fifth Circuit declined to stop it. And those are just the standing-related cases: There are also recent reversals on the shadow docket and on the merits.

“The Framers of the Constitution did not ‘set up something in the nature of an Athenian democracy or a New England town meeting to oversee the conduct of the national government by means of lawsuits in federal courts,’” Kavanaugh wrote, quoting from prior Supreme Court rulings. When the justices send a copy of their ruling back to the Fifth Circuit, they should bump up the font size on this part a few levels and put it in bold. Maybe this time it will finally stick.