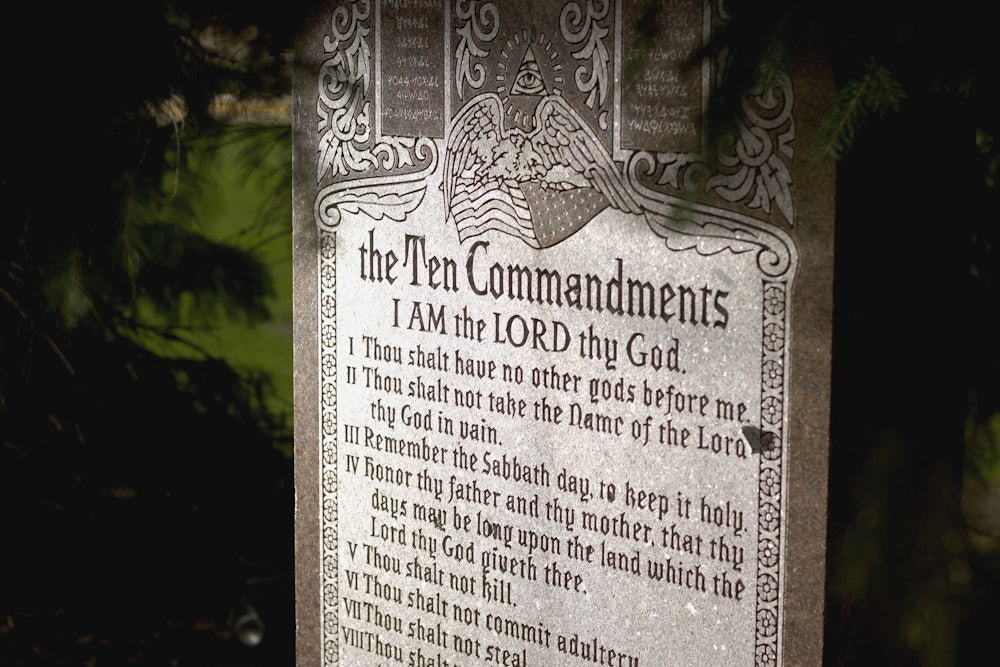

In 1978, Kentucky picked a fight with the U.S. Constitution. The state enacted a law requiring that a “durable, permanent copy of the Ten Commandments shall be displayed on a wall in each public elementary and secondary school classroom.” While the law claimed this was a “secular application” of the Ten Commandments, the U.S. Supreme Court saw otherwise. The justices ruled that the display violated the establishment clause’s separation of church and state, noting that it “had no secular legislative purpose” and was “plainly religious in nature.”

That 1980 ruling, Stone v. Graham, has effectively been the law of land ever since, but conservatives never gave up on the goal of that Kentucky law. This year, there are similar efforts underway in no fewer than nine states—and it’s clear that they expect a different ruling this time around from a staunchly conservative Supreme Court. Backers of these bills claim that American history proves their case, but they don’t seem to know or care about the full story. Their ignorance is terrifying, because the last time America had laws like this, it led to bloody street battles that ripped our cities apart.

Louisiana took the lead last year, passing a law in June—to Donald Trump’s approval—that would have required a Ten Commandments in all public schools come January 1. The ACLU filed suit, and a federal judge blocked the law in November, calling it “unconstitutional on its face”—but the state attorney general in January nonetheless instructed schools to post the Ten Commandments. A three-judge panel of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals took it up later that month, and its decision is pending.

In that hearing, state Solicitor General Jorge Benjamin Aguiñaga argued in court that recent Supreme Court rulings had paved the way for more religion in public schools. In 2022’s Kennedy v. Bremerton, for example, the justices ruled that public school coaches were free to pray at school with their students. That was because, as Justice Neil Gorsuch put it in the majority opinion, “this Court has instructed that the Establishment Clause must be interpreted by ‘reference to historical practices and understandings,’” and he went on to cite a 1963 ruling stating that “the line we must draw between the permissible and the impermissible is one which accords with history and faithfully reflects the understanding of the Founding Fathers.”

Religion in school was acceptable today, Gorsuch suggested, if it looked like the religion in the public schools of yesteryear. Conservatives took the hint. Aguiñaga argued in Louisiana’s appeal that Stone v. Graham was no longer relevant because those old displays were about religion. But today, Louisiana is only trying to teach children about the “historical significance” of the Ten Commandments.

In the meantime, bills and potential legislation are brewing in Montana, Texas, North and South Dakota, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania—and the backers of these efforts are making similar cases. They argue that their religious displays pass constitutional muster because they are simply restoring America’s public schools to their historical norms. The original bill in Louisiana, for example, insisted that public schools could display the Ten Commandments because that had been the tradition in American public schools for centuries, all the way back to the Puritans using the New England Primer in 1688.

In Pennsylvania, the bill’s sponsor, State Senator Doug Mastriano, says that the Ten Commandments are necessary in schools because “historical literacy is under attack.” Injecting religion into Pennsylvania’s public schools, Mastriano claims, will help “restore a sense of history.” Not to be outdone, one Texas legislator explained, “If you don’t know the Ten Commandments, you don’t really know the basis for much of American history and law.”

Clearly, the advocates of these bills are hoping to seize a moment of constitutional vulnerability. They want to send the question to today’s religion-friendly Supreme Court. Like Louisiana, they are betting that the Supreme Court will continue its destruction of the separation of church and state—and will be receptive to their claims about historical practices.

In one limited sense, they are not wrong. In the past, America’s public schools had lots of mandatory religion. In the Founding era and long after, public schools really were full of Bibles and Christianity. But it didn’t end well.

There has never been a way to include religion in public schools without also importing religion’s vicious and sometimes violent sectarian disputes. Some editions of the New England Primer—the book so beloved by Louisiana’s legislators—describe the Catholic pope as the “Man of Sins.” Not surprisingly, Catholic families didn’t appreciate the accusation.

In the 1800s, Philadelphia saw the worst of it. The city had a proud tradition of public education, rooted in the educational activism of its favorite son, Benjamin Franklin. The first state constitution in 1776 promised free public schools, and a law in 1802 led to the state’s first public school district in Philadelphia.

Those schools required students to pray in class and read from the Bible. But in theory, no student would be asked to do anything that went against their religious beliefs. It was assumed that the Bible itself, as well as common Christian prayers such as the Lord’s Prayer, were universal, above any single sect or denomination.

In theory, then, the city’s public schools were safe from any controversial religious teaching. But by the 1840s, Catholic leaders such as Bishop Francis Kenrick complained that the schools were full of “direct invective against Catholics.” Kenrick didn’t mind that schoolchildren were required to read from the Bible, but he did object to schools’ being forced to use the King James version.

Things quickly got out of hand. One Catholic teacher was fired for refusing to read from King James. Catholic students accepted classroom whippings rather than read from it. Fights broke out between Catholic and Protestant students, each calling the other heretics and bigots. Eventually, school district leaders agreed to a shaky compromise: If students and teachers could not in good conscience use the King James Bible, they could be excused.

Soon, however, anti-Catholic newspapers were warning that Catholics hated the Bible itself, and were out to destroy the public schools. Nativists like Philadelphia’s Walter Colton warned that Kenrick and the Catholic children were robbing Philadelphia’s Protestant children of a meaningful education, one that included mandatory readings from the King James Bible. Without those Bible readings, Colton wrote, public schools could only descend into “infidelity and crime.”

That was all it took.

Protestant militias mustered in the streets on May 6, 1844, to defend their vision of public schooling. Unlike in New York, where a more aggressive Catholic Bishop John Hughes had posted armed guards in Catholic neighborhoods and churches, Philadelphia’s Bishop Kenrick urged Catholic restraint.

Unfortunately, there was no restraint to be found. The militias attacked Catholic churches and houses, rampaging until the mayor declared martial law and U.S. Marines patrolled the streets. The violence continued for months, with the Marines even forced to wheel a ship’s cannon onto the streets to contain the anti-Catholic militias.

When the smoke finally cleared, at least four people were dead. Thirty houses had been destroyed, and two Catholic churches.

And why? Because some boosters insisted that their religion should be a mandatory part of public schooling. Like today’s proponents of the Ten Commandments in schools, Walter Colton insisted that there was nothing controversial about reading from the Bible. And without it, Colton wrote, a schoolboy would be missing the “most essential parts of his education.”

America learned this lesson the hard way. No, the display of the Ten Commandments in schools across the country probably won’t lead to riots in the streets. But our nation’s history proves that there’s no way to force religion into public education without turning schools into arenas for conflict.