Last week, the House Agriculture Committee approved a version of the farm bill, the sprawling piece of recurring legislation governing federal agriculture, conservation, and nutrition policy. Written by House Republicans, the bill was approved largely along party lines, with four Democrats joining all GOP committee members in voting to advance the measure.

This will likely not be the final form of the farm bill, which is approved roughly every five years in Congress. Most Democrats have bristled at the Republicans’ proposal, arguing that it is overly partisan; they are particularly concerned about how food stamp benefits would be calculated and rescissions to the Inflation Reduction Act, Democrats’ seminal climate policy bill, which passed in 2022.

The GOP farm bill would divert unspent IRA conservation funds to other priorities, out of a belief that climate-related policy should be determined by the states, rather than the federal government mandating farming practices that reduce emissions.

“Every state is different, because every state has different soil types, commodities, climate, weather patterns,” Representative Glenn “GT” Thompson, the Republican chair of the House Agriculture Committee, told me on Thursday. “We’ve always known that the most successful conservation investments are those that are locally led, incentive-based, and voluntary.”

But another element of the Republican bill would overturn a California state law that requires some meat products sold in the state to be produced under certain welfare standards. The potential ramifications of this California law, known as Prop 12, extend beyond agriculture. Opponents say that it would inhibit other states’ ability to implement their own regulatory policy.

“States would no longer be able to set consistent standards for meat and dairy products sold or consumed within their borders, potentially disadvantaging in-state producers, creating deregulatory pressure, and increasing food safety and quality risks,” said Kelley McGill, a legislative policy fellow at the Harvard Animal Law and Policy Clinic, in an email.

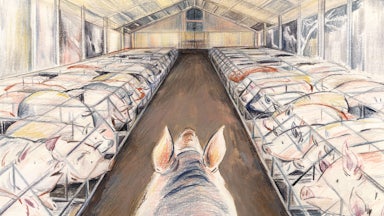

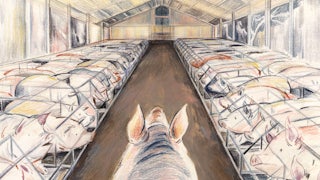

In 2018, California voters overwhelmingly passed Proposition 12, a ballot initiative that established housing standards for certain livestock. Prop 12 requires that farmers provide a minimum amount of space for laying hens, breeding pigs, and calves raised for veal, as well as specifically banning gestation crates, cages that are too small for pregnant pigs to even turn around in. This mandate applies to all covered products sold in California, and so affects producers outside of the state. Last year, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Prop 12, after out-of-state pork producers attempted to block it through litigation.

“Companies that choose to sell products in various states must normally comply with the laws of those various states,” Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in the majority opinion. “While the Constitution addresses many weighty issues, the type of pork chops California merchants may sell is not on that list.”

Shortly thereafter, Republican members of Congress introduced the Ending Agriculture Trade Suppression, or EATS, Act, legislation that would prohibit one state from regulating farming practices for food produced in another. Similar language was incorporated in the text of the House farm bill, which declares that “no state or subdivision thereof may enact or enforce, directly or indirectly, a condition or standard on the production of covered livestock other than for covered livestock physically raised in such state or subdivision.”

Rather than infringing on a state’s ability to determine its own regulatory standards, Thompson argued that this provision was in keeping with the redirecting of conservation funds, as a victory for states’ rights. “We respect [that] a state can mandate, intrastate, their own agricultural practices, but they can’t dictate to other states,” Thompson said.

Opposition to Prop 12 does not fall neatly along party lines. In February, Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack told the House Agriculture Committee that there would be “chaos” in the market if other states followed California’s lead. Vilsack later argued before the Senate Agriculture Committee that the California market is so large, out-of-state producers functionally have no choice to opt out of the state’s requirements.

“When you’re dealing with 12 percent of the pork market in one state, there is not a choice between doing business with California and not in California,” Vilsack said. “At some point in time, somebody’s got to provide some degree of consistency and clarity. Otherwise, you are just inviting 50 different states to do 50 different iterations of this.

But California’s law is not wholly unique. While Prop 12 has been the leading example of influential state policy, 14 other states have also passed laws banning certain types of confinement for livestock or instituting regulations for animal enclosures; like California, Massachusetts also approved similar policy by ballot measure.

“The long-standing status quo under our federalist system,” McGill said, “is for states to be able to regulate products that enter their borders—so long as such regulations do not impermissibly discriminate—and states have long exercised that right across many aspects of agricultural production and points all along the food supply chain. Prop 12 will lead to no more chaos than will those existing state provisions.”

Experts further warn that overturning Prop 12 might not mitigate the regulatory chaos. In a November open letter sent to congressional leaders, 30 law professors warned the EATS Act would “initiate years of lengthy court battles to resolve the act’s constitutionality and derive the act’s scope, as well as an endless flood of concurrent challenges to innumerable state and local laws.” Overturning Prop 12 via legislation “would create a staggeringly uncertain legal and regulatory landscape,” the letter said. “The result would surely be an unprecedented chilling of state and local legislation on matters historically regulated at the state and local level.”

Producers are also divided on on Prop 12. The National Pork Producers Council vehemently opposes the policy, as do other large agricultural coalitions; but some individual producers are in favor of Prop 12, in part because they believe it’s better for smaller farms that have been pushed out by the large-scale pork production industry. Other producers have already invested significant funds in preparing their farms to meet Prop 12’s requirements.

Thompson believes that heeding these standards results in higher costs, which then leads to poor and middle-income Americans being unable to purchase pork products. “When people can’t afford their bacon, they’re going to rise up, and there will be a future proposition that repeals it,” Thompson predicted about the future of Prop 12 in California.

A September survey by Purdue University’s Center for Food Demand Analysis and Sustainability found that 32 percent of consumers would decrease their purchases of pork products due to a general price increase. However, when respondents were asked about price increases due to Prop 12, fewer consumers said they would decrease spending on pork if they knew the cost hikes were related to animal welfare. A 2022 poll by Data for Progress, a liberal think tank, further found that 80 percent of likely voters believe farm animal welfare is a moral concern.

The farm bill provision that would overturn Prop 12 also has potential ramifications for health outcomes: In a 2022 amicus brief to the Supreme Court, several public health organizations and experts wrote that Prop 12’s requirements “protect the health and safety of Californians.” Intensive confinement of pigs results in weaker immune systems and increased growth of pathogens, and the close quarters of gestation cages “facilitates the transmission and mutation of pathogens into more virulent forms that can be transmitted to and sicken, or even kill, humans.”

Although the provision in the farm bill is slightly narrower than the language of the EATS Act, McGill warned that its passage could make it more difficult for states to regulate “the sale of meat and dairy products produced from animals exposed to disease, with the use of certain harmful animal drugs, or through novel biotechnologies like cloning, as well as adjacent production standards involving labor, environmental, or cleanliness conditions.” Those who think Prop 12 shouldn’t be overturned thus worry about the ramifications not only for animals but for the humans consuming meat products.

It’s unclear whether this provision will end up in the final version of the farm bill—it has significant opposition from hundreds of Democrats in Congress, as well as some Republicans, which could ultimately result in it being excised from the final bill. But Senator John Boozman, the Republican ranking member of the Agriculture Committee, noted that Congress has the authority to legislate on an issue after the Supreme Court has made a decision; if it’s removed from the final text of the farm bill, there’s still an opportunity for supporters to append it. “We’ll either have it in the base bill, or it will come up as an amendment,” Boozman said.