A few weeks ago, the egg shelves at my local Whole Foods in New Orleans were nearly empty. A note, citing an egg shortage, limited customers to no more than two cartons apiece.

Oh no, I thought. It’s back.

Last summer, on a reporting trip for this magazine, I visited a rural Nebraska county where several chicken farms had been hit by avian influenza. Local farmers were forced to slaughter nearly a million birds—just one small sliver of a national massacre. Some 58 million birds were culled throughout 2022.

The disease is carried by migrating waterfowl and was waning during my visit, since the birds had already passed north in the spring. But the outbreak’s impact was already clear in supermarket aisles, where the average cost of a carton increased from $2.05 in March to $3.12 in August. And as the birds winged south again last fall, the flu returned. Once more, millions of birds were euthanized. In December, prices hit a record high: $4.25 per dozen, more than double what consumers were paying a year earlier.

The number of avian flu infections has waned as ducks and geese moved further south, and by mid-January wholesale prices had dropped by a dollar, which augured coming price drops for shoppers too. Farmers are slowly restocking their flocks. Nonetheless, the media has been in an egg frenzy, with stories detailing everything from cross-border egg smuggling to a boom in backyard chickens. One farmer in Idaho has apparently found a profitable niche by freeze-drying and pulverizing his eggs; the powder, which costs about $20 per dozen eggs, lasts more than two decades. The news cycle hit its nadir last week, when Fox News’s chief conspiracist, Tucker Carlson, suggested that the Biden administration and mainstream media were covering up the real causes of the egg shortage: chicken farms burning down and commercial feed that causes impotence.

Mostly, though, the coverage has pondered one question: Why are eggs so pricey? The answer is relatively straightforward. Yet the egg panic should be raising bigger questions: Might this virus jump to humans, and can anything be done to stop it? These answers are more complicated and may depend on whether we’re willing to give up cheap eggs.

Modern egg farms are less agricultural than sci-fi dystopian. The birds are stuffed into cages that offer less than a single page of printer paper’s worth of space; the cages are stacked, row after row, with some facilities housing more than a million birds. The feed is carefully formulated, the light deliberately manipulated so that the hens are tricked into churning out as many eggs as possible.

For an influenza virus, such barns are paradise. Since the chickens have been engineered to maximize egg production, they’re genetically identical—a buffet of bodies where disease spreads rapidly. The only option for industrial farmers after a bird tests positive, then, is to slaughter every single one in the facility. But the problem goes beyond the size of these cullings. “These birds are immunologically naïve and act as an enormous amplifier of the virus,” virologist Michelle Wille told me last summer. “This obviously means that we have enormous reservoirs for avian influenza ... and increases risk for viral transmission. It is with this enormous amplification that we see zoonotic spillover events.”

Mammals generally cannot contract bird flu. Every once in a while, though, evolution allows for a trans-kingdom leap. The pandemic of 1918—the worst in modern history, with a mortality rate 30 times higher than Covid’s—originated from a bird flu virus that jumped into human populations, possibly on a Midwestern farm.* Another scary wave of bird flu hit Hong Kong in 1997, when 18 people were infected and six died, a staggering mortality rate. As I noted in my investigation for The New Republic last year, this outbreak was likely prompted by the recent arrival of intensive chicken production in China.

In the years since, the disease has slowly spread across the globe, hitchhiking in the bodies of wild birds, which often show no symptoms. Leaps into domestic poultry were rare; the last U.S. outbreak occurred in 2014. But once the virus hit our farms, it grew more contagious, according to officials from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. This strengthened virus spread from farm to farm until, after a then-record 50 million birds were euthanized, the epidemic was contained.

The current strain of influenza—which has now reached five continents—first hit the United States last February. It’s morphed again, it seems, and now is transmitted much more easily from wild birds into domestic poultry. Rather than farm-to-farm spread, the majority of 2022 cases seem to have been separate infections from migrating birds.

It seems quite possible, then, that every migratory season our industrial chicken farms will become oversize petri dishes for a potential superflu. What makes that particularly scary is that the current strain is already too super. Far more mammals were infected last year than in 2015, and while federal authorities suggest that the current virus poses low risk for humans, several people have tested positive, including one in the U.S. Last month, there was a dire new milestone: On a Spanish mink farm, the virus proved capable of spreading from mammal to mammal—a “warning bell,” according to one veterinary researcher. If the virus learns to spread from human to human, we have another pandemic on our hands.

The position of the Agriculture Department, as relayed to me by a spokesperson, is that the “current outbreak has impacted all types of farms, regardless of size or production style.” The department’s data tells a different story, though: More than half the deaths occurred at just 20 egg farms, each home to more than a million laying hens.

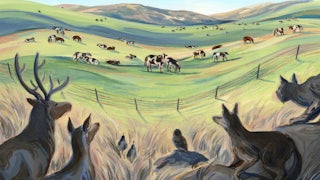

It’s not that small farms are immune to this disease. Dozens of tiny flocks have been hit: backyard collections, mostly, raised by hobbyists who perhaps aren’t always as cautious as professional farmers, so the birds—or the hobbyists themselves—wind up walking through infected piles of goose poo. You might think of a typical “small commercial farm” as having somewhere between 15,000 and 25,000 hens. Several companies, like Vital Farms and Pete and Gerry’s, buy pasture-raised eggs from such farms to distribute to national retailers. The USDA data shows that only three farms on this scale have contracted the virus.

Last summer, during my initial reporting on bird flu, I spoke to several farmers who raise chickens at this scale. One suggested he existed in a kind of Goldilocks zone: He’s more cautious than backyard growers, but, unlike the big farms, he does not have low-wage employees coming and going from his facility. “We have less exposure to wild bird populations, and we have less exposure to human traffic,” he said. Tom Flocco, the CEO of Pete and Gerry’s, noted that since the farmers he works with don’t use antibiotics, they already have strict biosecurity in place. “They walk through their barns and pastures every day, monitoring the health and well-being of their flocks,” he said. “They aren’t simply employees at an egg factory; their farms are their livelihood, and they are deeply invested in the health of their hens.” A food system with many smaller flocks is also inherently more resilient: Even if Pete and Gerry’s suffered an outbreak at one farm, the losses would be a tiny fraction of their overall supply. (So far, none of the company’s farms have been infected, Flocco said.)

Flocco noted that the retail prices for premium eggs are up 20 percent year over year, mostly because the cost of feed doubled due to the war in Ukraine. Conventional eggs, he said, are up 130 percent. That’s helped upend the economics of the egg industry: Cal-Maine, the country’s largest egg producer, has been selling its “specialty eggs”—a broad category that includes organic, pasture-raised, and cage-free eggs, among other labels—to retailers for 50 cents less per dozen than its conventional product.

But to focus only on grocery-store prices is to miss the full costs of eggs. The 2014–2015 crisis cost the federal government $879 million, including indemnities paid to chicken companies. According to one estimate, the ripple effects across the U.S. economy reached $3.3 billion.

This year, with a higher death toll, the government will likely spend more. The big chicken companies, meanwhile, are doing just fine. Cal-Maine recently announced record-setting quarterly profits, which has prompted accusations of price gouging. It does seem fishy that a relatively small drop in egg supply can drive such huge jumps in price, but the real cause is more likely to be the unique economics of eggs. This is a staple product with few good substitutes, which means demand is inelastic; even a small drop in supply forces a big jump in price before buyer behavior will change. Collusion or not, the outcome is the same: The spread of bird flu means you spend more in the checkout aisle and more on tax-funded cleanup, while the big companies reap more profit. What incentive do they have to quash this disease?

It’s not clear how quashable the virus is anyway. Mike Stepion, a USDA spokesperson, told me that the best form of protection is keeping wild birds separate from poultry. Wille, the virologist, agreed—noting that, for obvious reasons, this is hard to do with pasture-raised birds. The “pasture-raised” label does allow farmers to move their birds into barns for their safety, and Flocco said Pete and Gerry’s has asked farmers to do so whenever there is a nearby outbreak. That will inevitably happen more in the coming years.

If less dense flocks can help prevent spillover, it strikes me as a practice worth pursuing. Since my trip to Nebraska, I’ve been buying eggs I know come from smaller flocks. They typically cost me around $7 per dozen—a steal, by my math, if it means preventing a pandemic on the scale of Covid-19, which cost the U.S. an estimated $16 trillion.

Rapid change is possible, as recent history shows. In 2015, just 6 percent of egg-laying hens in the U.S. lived cage-free; within five years, thanks to a wave of legal bans, nearly a third of the national laying flock was raised outside a cage. To stop a pandemic, we’ll have to go further, but it shouldn’t mean everyone pays $7 per carton. Andrew deCoriolis, the executive director of the nonprofit Farm Forward, pointed out that the current prices are due to markup. With conventional eggs providing a cheap alternative, grocery stores can artificially raise the prices of ethically raised eggs—often charging more than twice what they pay to the egg companies, he said, according to the figures he’s seen.

“Yes, giving animals access to pasture or raising breeds of chickens with more robust immune systems costs more, but it doesn’t cost 3x more [than conventional practices],” deCoriolis wrote to me. “Reducing pandemic risk in the poultry industry will increase the price of products, but we don’t really know by how much because so few companies raise animals in these conditions, and those that do … haven’t reached meaningful economies of scale.”

We may not be able know the true price of such eggs, then, until we make such conditions mandatory. But it’s a safe bet that they’ll be far cheaper than one more global catastrophe.

* This article has been updated to clarify the origins of the 1918 flu virus.