Back in 1982, a young Detroit man named Vincent Chin went out to a bar with his friends to celebrate his wedding, which was to take place the next day. Chin, who was born in China, never made it to the wedding, because he was beaten to death with a baseball bat.

All the men involved worked in the auto industry. A draftsman working for an auto supplier, Chin got into an altercation with two white men over an exotic dancer’s tip. Either Ronald Ebens, a foreman for Chrysler, or his stepson, Michael Nitz, a laid-off Chrysler worker, called Chin and his friends “little fuckers,” who were “the reason we’re all laid off.” Outside the bar, Chin called the white men “chickenshit,” and the two chased Chin—who they referred to as “the Chinaman”—with a baseball bat and beat him hard; he died of his injuries a few days later.

You could say that the cause of this tragedy was men drinking and, thus, failing to let a minor conflict blow over. Many such cases! But Vincent Chin’s murder also had its roots in the racist culture of the time. In the 1980s, there was tremendous anxiety in America that Japan was going to economically surpass the United States. Those anxieties were expressed in intensely nationalistic ways, particularly in the auto industry, with many workers concerned about losing their jobs to foreign competition. “Park your import in Tokyo,” read a sign in the parking lot by the United Auto Workers headquarters. An AP photo taken the year before Vincent Chin’s death shows UAW workers destroying imported cars with sledgehammers.

That decade is now known for a “yellow peril” panic: Anti-Japanese racism was common, and in cities like Philadelphia and Boston, Asians were more likely to be the targets of hate crime than any other minority group. Politicians stoked it too. The year Chin was murdered, auto industry champion and Congressman John Dingell of Michigan referred to Japanese automakers as “little yellow people.”

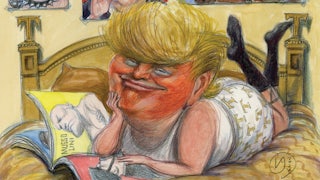

Donald Trump, who first came to prominence in the 1980s, seems to be trying hard to single-handedly bring back that awful decade and the type of panicked, racist frenzy that killed Vincent Chin. His recent remarks about Chinese electric vehicles sound particularly dangerous. Trump has been claiming—falsely—that Biden’s electric vehicle policies will allow a flood of Chinese imports (the administration’s policies support the growing domestic E.V. industry) and put Americans out of work. He promised a “bloodbath” if he lost the election, linking the fantasized violence to these imports, insisting, “They’re not going to sell those cars.” (United Auto Worker president Shawn Fain was unimpressed, saying, “Trump only represents the billionaire class, and he doesn’t give a damn about the plight of working-class people—union or not.”) Experts interviewed by The New York Times noted that Trump’s language about E.V.s is consistently violent: They will “kill” or amount to an “assassination” or a “hit job” on American jobs.

Trump’s rhetoric seems fringe and erratic. But coming from the putative leader of the Republican Party, such talk has a broader impact. In an apparent flashback to that 1981 sledgehammer scene, there have been numerous reported instances recently of vandalism at E.V. charging stations, complicating consumers’ efforts to charge their vehicles. Worse, Trump’s stoking hostility toward an already vulnerable group. Even before this recent vendetta on E.V.s, the Trumpist impulse to blame all Asians for the Covid-19 pandemic had led to a surge in anti-Asian racism, which has continued, with hate crimes widespread and nearly half of Asian Americans saying they have experienced discrimination. Some states have been trying to ban Chinese nationals from buying property; Florida actually passed such a law, though a federal court blocked it in February, and policymakers in Texas, Lousiana, and Alabama are considering similar racist restrictions.

This unhinged response to a trade war has a more mainstream—and Democratic—political analogue, as well. Anti-Chinese rhetoric is bipartisan, and although Trump and Biden have real differences on electric vehicles, their specific policies on China have been remarkably similar. In late February, Biden announced that the Department of Commerce would “conduct an investigation” into whether Chinese-made vehicles could be used for spying and sabotage—part of his promise to “make sure the future of the auto industry will be made here in America with American workers.” It’s good to protect American workers and union jobs, but this administration always manages to frame that worthy goal in the most paranoid way possible. The Biden administration routinely makes statements and gestures that seem alarmingly bellicose, like engaging in military provocation in the South China Sea. And speaking of paranoia and aggression, Democrats’ support for banning TikTok is embarrassing, likely to hurt the party with young voters, and simply a foolish look in a world of global communications from a nation that allegedly values free speech.

Violent rhetoric from politicians against specific minority groups, reinforced by real violence carried out at the grassroots, is a pattern with alarming historical precursors, whether in Nazi Germany or the antebellum American South. It doesn’t really matter whether you call it fascist or not—it’s scary and needs to stop. Vincent Chin died from exactly this sort of climate, fueled by American anxiety about who was making our cars. All Americans should shun Trump’s efforts to stoke a repeat of that nationalist violence. We should reject such poison when it comes from Democrats too.