For years, America’s most prominent consulting firms have been competing against one another to service the most heinous regimes on the planet, offering their efforts and advice for tyrants and kleptocrats looking to expand their reach and their repression. Even as investigators and officials have targeted other, similarly nefarious elements of America’s foreign lobbying industry, these major consultancy organizations have largely avoided scrutiny.

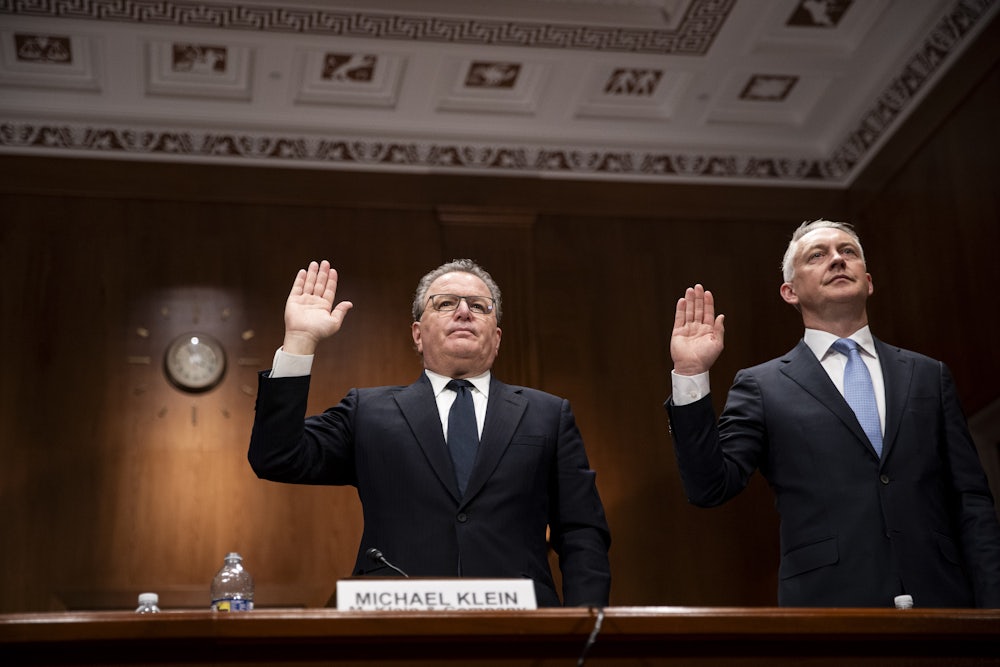

That all changed last week, when congressional officials held a hearing examining these consulting groups specifically, which offered fresh revelations about how dictatorships suddenly have a new tool to keep American officials, and the rest of us, in the dark about what these consulting groups are actually doing.

The hearing, hosted by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, focused on how groups like McKinsey, Boston Consulting Group, and Teneo were working for Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, better known as the Public Investment Fund, or PIF. Worth nearly $800 billion, the PIF has overseen Saudi Arabia’s recent spending splurge on everything from sports to tech to telecoms. Much of it has been predicated not only on the Saudi regime diversifying its oil-rich economy but also on laundering the dictatorship’s image, battered as it is by things like the assassination of journalists and the jailing of women’s rights protesters. And much of that effort has, by all appearances, come with the help of American consulting groups, which have helped to steer Saudi efforts to whitewash the country’s reputation.

There’s only one problem. As senators discovered while grilling the witnesses, these consultants claimed they couldn’t reveal what, precisely, they’re actually doing on behalf of the Saudi regime, or even how much money they’re making in the process. Mind you, they all claimed to want to reveal what they were doing and that they wanted to comply with senators’ subpoenas for information—but they couldn’t do so because of a particular occupational hazard: threats from the Saudi regime itself.

Led by Democratic senator and PSI chair Senator Richard Blumenthal, the hearing centered on the consulting groups’ lack of compliance with the committee’s previous requests for documents about their work in Saudi Arabia. Over and again, the consultants claimed that, unfortunately, their Saudi work had to be kept secret, even from American legislators, because revealing it would contravene Saudi law.

According to Rich Lesser, head of the Boston Consulting Group, his organization is “caught between two sovereigns,” with Saudi officials being “explicit” that complying with subpoena requests is “a violation of Saudi law.” McKinsey partner Bob Sternfels said much the same, claiming that complying with congressional subpoenas “could result in civil or criminal penalties” in Saudi Arabia. Teneo CEO Paul Keary—who claimed that Teneo is a “proud American company”—also pointed to Saudi threats as the reason his organization couldn’t fully reveal its work for the Saudi regime.

It was the first time that legislators had actually held consultants’ feet to the fire for their work on behalf of the world’s dictators. But the entire hearing itself was, in some ways, a dull affair, with senators rephrasing their demands for documents and the consultants sputtering over and again that they couldn’t comply. Still, for those who sat through the hearing itself, the implications were clear: Not only had American consulting groups injected themselves directly into some of the world’s reprehensible regimes but, as Saudi Arabia illustrated, dictatorships could now prevent those American consulting companies from revealing what exactly they’re doing, even after congressional demands. “You say you are [caught] between a rock and a hard place, but you have chosen sides,” Blumenthal at one point said. “You have chosen the Saudi side, not the American side.”

Pulling back, the implications of the companies’ claims were shocking. For the first time, American organizations claimed they couldn’t reveal the scope of their pro-dictatorial efforts because of threats from those same dictatorships. It was an unprecedented defense for stymying efforts at foreign lobbying transparency—and one that could set a debilitating precedent moving forward.

This wasn’t lost on legislators. As Blumenthal said, if the consultants’ defense stands, it “would create a dangerous and unsupportable precedent—that American companies can shield commercial interactions with foreign governments that are directed towards the United States from oversight simply by choosing to have their contracts governed by foreign law.”

It’s unclear what, exactly, comes next. Blumenthal hinted at further moves to strengthen the Foreign Agents Registration Act, or FARA, which forces foreign lobbyists—including consulting groups—to disclose their efforts on behalf of foreign regimes. Whatever the next step may be, it’s obvious that these consulting groups have hit upon a new method for dodging transparency requirements—one that other foreign lobbyists, and other authoritarian regimes, will likely be eager to follow moving forward.

Then again, maybe this was inevitable. Even as legislators in recent years have focused on other prongs of America’s foreign lobbying nexus—not least the roles that U.S. public relations and law firms play in propping up dictatorships around the planet and acting as their mouthpieces in Washington—American consulting groups have largely escaped notice. This lack of focus on consultancies has given those regimes time to craft their own domestic legislation that will force consultancies to keep their work for those regimes secret.

Despite their sputtering defenses, there’s little evidence these consulting groups ever thought twice about such arrangements. Groups like McKinsey, for instance, have been working in Saudi Arabia for years, not only opening doors for Saudi officials in Washington but even going so far as to identify critics of the Saudi regime—all of whom the regime then targeted, arresting either the critics or their family members. Even while they claimed they were “horrified” by the Saudis’ crackdown, that did little to dissuade McKinsey from partnering with the dictatorship’s sovereign wealth fund, expanding Saudi influence that much further in the process.

The details of that work, however, are still unknown. And it is only darkly ironic that it is now McKinsey that is facing a potential crackdown from the Saudi regime—and presenting a lesson in the perils, and the threats, of foreign lobbying for the rest of us.