On June 6, Saudi Arabia bought the game of golf. That is an exaggeration—rest assured, America’s country clubs are still controlled by a cabal of madras-clad local oligarchs—but only slightly. Technically, the upstart, Saudi-backed LIV Golf announced that it was merging with the Professional Golfers’ Association, ending a bitter feud that had divided the sport for over a year. In reality, though, it was more takeover than merger. While details of the new entity are subject to change, two things are clear: It will be funded to the tune of over a billion dollars by the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF), and the fund’s governor, Yasir al-Rumayyan, will serve as its chairman. In one shocking power grab—most of the PGA’s board was kept in the dark—Saudi Arabia assumed control of an entire professional sport.

That Saudi Arabia’s arid climate is not particularly well-suited to golf—its July highs typically hover in the mid-110s—only underscores that this is not really a sports story at all. The kingdom’s takeover of professional golf is a part of a larger strategy aimed at maintaining geopolitical economic relevance in a world rapidly transitioning away from fossil fuels, while burnishing its global image. This is sports washing on a scale never seen before, a gargantuan effort to extend and protect Saudi global power.

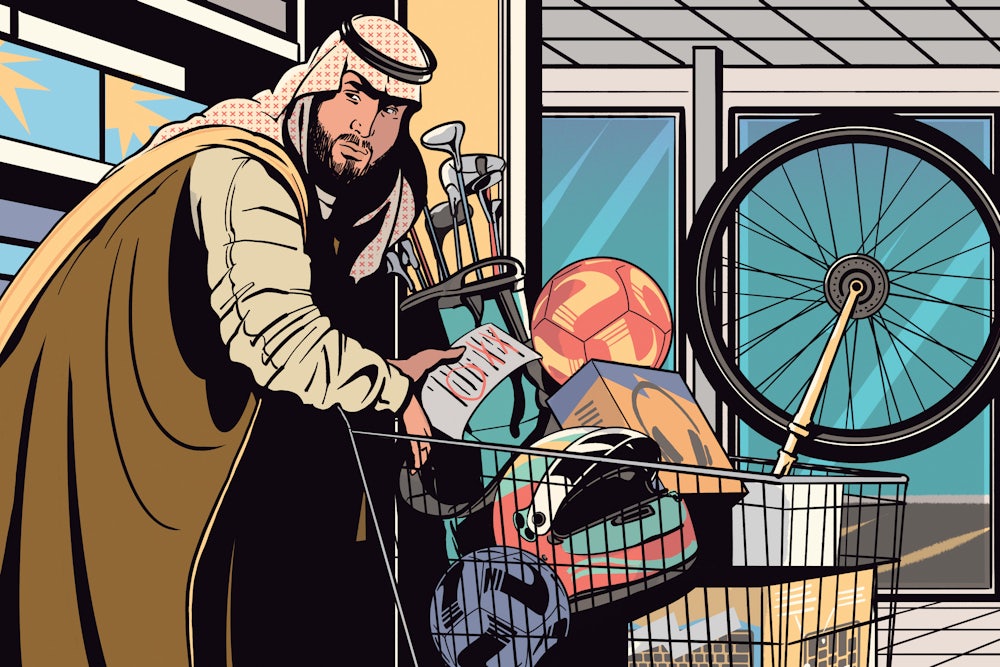

The spending spree isn’t limited to golf. In recent months, the Saudis increased their investments in Formula 1 racing, boxing, and cycling. PIF is also expected to close a multiyear deal with the Association of Tennis Professionals to bring the sport’s Next Gen finals to Jeddah. And in the wake of the 2022 World Cup (hosted by longtime rival Qatar), the Saudis have lured stars like Cristiano Ronaldo, Karim Benzema, and N’Golo Kanté to its Saudi Pro League with eye-popping salaries: Ronaldo reportedly makes more than $200 million per season; the oft-injured Kanté makes just half that much.

It’s not only sport. “Saudi Arabia is investing huge amounts of money in 14 or 15 different sectors,” including “alternative energy sources, tourism infrastructure, even in their movie industry,” said Simon Chadwick, professor of sport and geopolitical economy at Skema Business School in Paris. “Fundamentally for me, it’s all about security.” That security, according to Chadwick, has two elements. First is the country’s sizable youth population—70 percent of Saudis are under 35—and worries about religious radicalism, but, in Chadwick’s term, the “bigger concern” is “another Arab Spring.” The second element is economic. Saudi Arabia is currently highly dependent on oil, and “the long-term security of that economy is weak, especially in a world kicking back against fossil fuel production. In essence, Saudi Arabia has 20 years to diversify its economy: This is about creating a more secure, resilient post-oil-and-gas economy in addition to protecting the country’s royal family.”

Of course, improving the country’s reputation of oppression wouldn’t hurt either. Saudi assassins, at the orders of their crown prince, bone-sawed dissident Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi in a Saudi Consulate in Istanbul in 2018. The military oversaw a devastating, yearslong blockade in Yemen that resulted in mass starvation and death. Within the kingdom, homosexuality is often punished, women’s rights are still severely curtailed, and executions are frequent. Buying into sports is a rebranding effort. It’s also aimed at luring skeptics and tourists to a country that has settled on a post-oil identity: that of a destination vacation site, a lavish Las Vegas-by-the-Gulf.

These moves also underscore the general sense of impunity with which the Saudis have operated for decades. Buying golf is perhaps best understood as a power game: It shows that the Saudi government can murder an American resident and then, in just a few years’ time, buy an American sport. And it has also created a wedge between the PGA and the U.S. government, which has raised antitrust and human rights concerns about the Saudi partnership. (The Department of Justice is currently investigating the PGA’s audacious and impudent plan to maintain its tax-exempt status in the wake of its Saudi takeover; the merger may be blocked on antitrust grounds.) Similarly, many European soccer teams are cash-strapped and still haven’t recovered from the pandemic, making them increasingly dependent on money from the kingdom. It seems likely that Saudi teams will play in the UEFA Champions League in the near future, and that the country will host both European Cup finals and the World Cup. Even reviving the much-maligned Super League is hardly out of the question.

This will change global sports. It will change global culture. But Saudi Arabia doesn’t really care about that. This is about power and money, and little else.