Not so long ago, socialism was on the up. Back in 2019—after Bernie Sanders’s first electrifying primary run, after tens of thousands flocked to the Democratic Socialists of America, after a diverse group of young, left-wing insurgents won elections to Congress and were anointed “The Squad,” after socialists started actually winning elected office at the state and local level—a glossy spread in New York magazine asserted, “Pinkos Have More Fun.” Once tarred as a redoubt for argumentative academics and crusty Soviet holdouts, socialism was suddenly popular. Indeed, for a brief, shining moment in February 2020, it looked like Sanders was on track to capture the Democratic nomination; multiple legacy publications were calling him “unstoppable.”

But then, of course, Joe Biden won the South Carolina primary, then the nomination, then the 2020 election. DSA started losing members, high-profile left candidates in Philadelphia and Buffalo lost mayoral elections, and critical comments increased in volume. This July, for instance, the iconoclastic leftist writer Fredrik deBoer decried the most recognizable figure in the Squad, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, as “Just a Regular Old Democrat Now.” Pointing to her vote to enforce a contract on overworked railroad workers (and thus prevent them from striking)—a vote she cast along with fellow Squad members Cori Bush and Jamaal Bowman—deBoer lamented “AOC’s increasingly half-hearted attempts to cover up her genuine predilections with the most superficial of symbolic acts.” The next month, in August, the journalist Ross Barkan asked in the pages of this magazine, “Has the Socialist Moment Already Come and Gone?”

That summer, the answer was complicated. While Biden is hardly a man of the left, activists had succeeded in pushing him to sign landmark climate legislation and even attempt to cancel billions in student debt. While conservative Democrats continued to dominate Congress, democratic socialist politicians held office across the country. And while some of the highest-profile had “occasionally fallen short,” the journalist Branko Marcetic noted in a response to deBoer, members of the Squad had accomplished some truly impressive things (e.g., forcing the end of the USA Patriot Act’s warrantless collection of phone metadata, clearing the way for new public housing construction, assisting in major unionization efforts and state-level environmental initiatives).

In recent months, left politics have been even further scrambled by Israel’s bombardment of Gaza, which experts have labeled a genocide. As the largest antiwar demonstrations in 20 years erupted across the country, almost every Democratic politician—including Sanders and Elizabeth Warren—refused to call even for a cease-fire. Such reluctance led the journalist Hamilton Nolan to conclude that the “Bernie Era of the American Left is over.” The few members of Congress willing to demand an end to the Israeli military’s ruinous campaign—a number that includes Ocasio-Cortez, Bush, Ilhan Omar, and Rashida Tlaib (the only Palestinian American in Congress)—were, he wrote, the “new political leaders of the Left.” Yet their era may well be brief. The American Israel Public Affairs Committee, or AIPAC, is reportedly planning to spend $100 million to defeat the Squad, a staggering sum that could quite possibly result in the expulsion of these new leaders from political office.

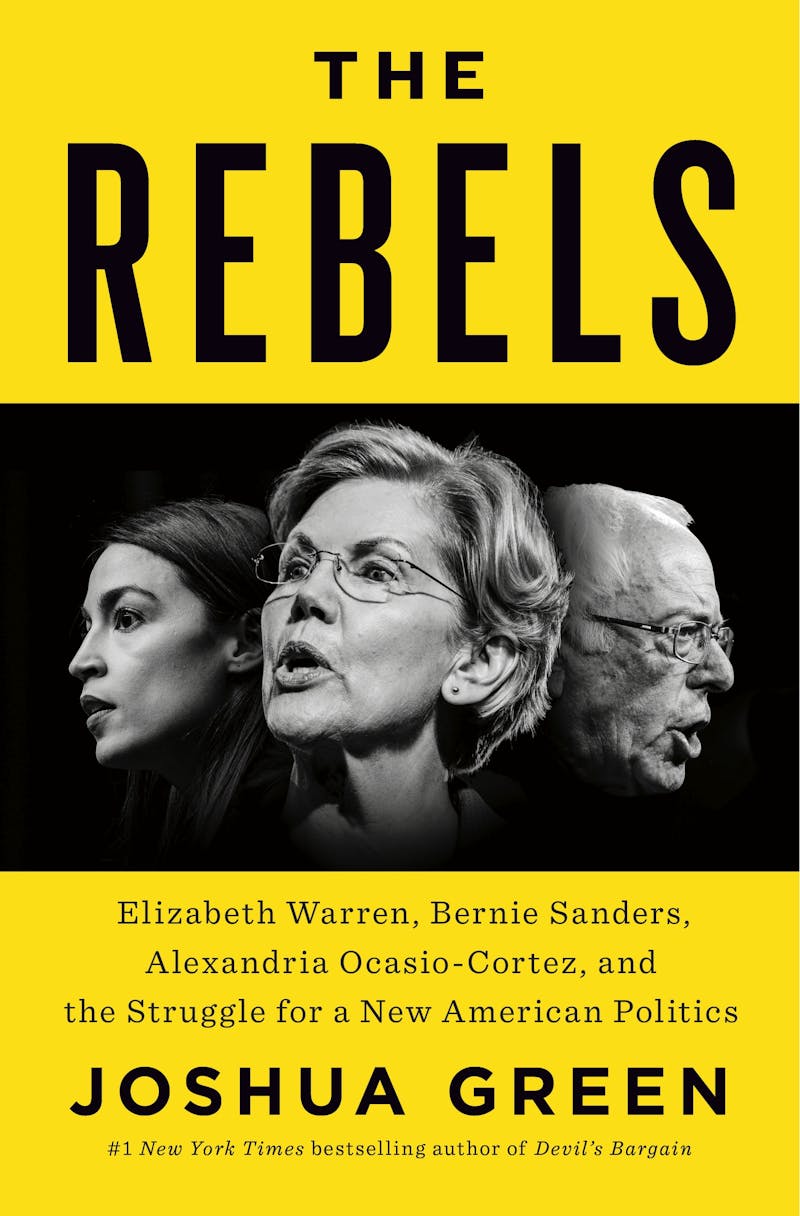

In such a moment—of uncertainty, of jeopardy, of possibility—it’s no surprise that a number of books are appearing that seek to explain the state of the political left. Who are its leaders? What are their goals? The Rebels: Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and the Struggle for a New American Politics, by Bloomberg journalist Joshua Green, takes on the ambitious task of providing a comprehensive answer. The result, which situates its subjects within a broader history of party power struggles, provides a clear and satisfying narrative of the last 15 years of Democratic politics. Yet the book’s near-singular focus on only the highest-profile elected leaders unfortunately ignores a great many of the forces that have fought to shape the future of the broader political left—and are fighting still. By looking more closely at reformers than at rebels, The Rebels narrates a “struggle for a new American politics,” but not the struggle.

Green’s story largely begins in 2008, with an economic collapse. Huge financial institutions buckled, then broke; the stock market plummeted. “Millions of Americans lost their jobs, their homes, their retirement accounts, or all three, and fell out of the middle class,” Green writes. “Millions more were gripped with the gnawing anxiety that they could be next.” Out of this cataclysm emerged the presidency of Barack Obama, benefiting from voters’ anger at the governing Republican Party and desire for a fresh, new approach.

Yet, despite his campaign’s constant promise of “change,” Obama’s approach to the recession “was the area where he might have differed the least from his predecessor.” As a candidate, he had received almost twice as much money from Wall Street as John McCain; as president, Obama surrounded himself with conservative financiers like Larry Summers and Timothy Geithner. These elite administrators swiftly oversaw the transfer of hundreds of billions of dollars to the country’s largest banks, yet stopped short of providing equivalent assistance to struggling families—which, Green notes, had just seen their average net worth drop 20 percent in a mere 18 months. Many of these individuals exploded in outrage when news broke that Wall Street executives were using bailout money to pay themselves huge bonuses, but the Obama administration quietly snuffed out efforts at clawing that lucre back.

At the time, “there was still no meaningful left-wing economic critique to provide a compelling alternative vision,” Green asserts. (More on that later.) “But that was about to change.”

Enter Elizabeth Warren. In Green’s telling, the then-obscure Harvard law professor was preparing a peach cobbler when, in 2008, she received a call from Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, inviting her to chair a panel overseeing the bailout money earmarked for Wall Street. Warren leapt at the opportunity, and from her perch atop the oversight panel she quickly attracted an ardent following by grilling Geithner for failing to change the management of the banks, humiliating Treasury Department brass for overpaying financial institutions, and generally furnishing a trenchant appraisal of the prevailing economic approach of both major political parties. Viral videos and breathless press coverage turned her into “a kind of folk hero.”

Warren hoped to parlay her newfound celebrity into a role as head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, a new agency she had lobbied the administration to create, but Obama “feared running afoul” of the financial industry and passed her over. Casting about for a next move, Warren—who had once told a journalist she’d rather “stab myself in the eye” than run for Senate—decided to run for Senate. It was “the first real electoral test of left populism in the aftermath of the financial crisis,” Green writes, and—as she’d always done—Warren aced it. Landing on the Senate’s Banking Committee, she immediately began lacerating regulators and bankers, exemplifying what Green labels “a new way” to govern atop the national stage: “to have big, loud, messy fights that offered moral clarity and galvanized public sentiment behind a position. She used this power to take on her own party.”

In her first term in the Senate, Warren gained so much popularity in exposing the revolving door between Wall Street and the Obama administration that two separate grassroots campaigns sought to recruit her to run for president in 2016. Fearing a loss and hoping to influence the likely victor (Warren had quietly “developed ties to Clinton”), she declined. The “disappointed organizers” of the Draft Warren movement turned instead to Bernie Sanders—even though, according to Green at least, “practically no one outside Vermont knew who he was.” In mere weeks, Sanders’s run had become a phenomenon, driven in significant part by downwardly mobile millennials, underemployed and saddled with debt. Left-wing activists—many of whom had previously “rarely bothered to try to influence the party platform or the leading candidate for president”—turned his campaign into a crusade.

Sanders did far, far better than expected but still fell short, a result with myriad explanations—including, in some small part, Warren’s decision not to endorse him (a calculation that earned her vitriolic blowback but serious vice presidential consideration by the Clinton camp). Yet his insurgent campaign—and the ultimate victory of Donald Trump—fundamentally altered the American political calculus, shaking neoliberal orthodoxy, defined by Green as the “conviction that market logic should be rigorously applied to all aspects of public policy.” Clearly, outsourcing public services to the private sector wasn’t cutting it, practically or politically.

Expressions of “resistance” to Trumpism filled the streets, although—as Green notes—the marchers were ideologically diverse and included many conventional liberals. Still, the Sanders campaign had given leftist politicos experience and connections, and many began organizing explicitly left-wing runs for office. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a bartender and former Sanders volunteer, decided to take on one of the most entrenched centrist Democrats in Congress, her campaign powered by Sanders veterans and new organizations explicitly devoted to electing leftists. Much to the surprise and chagrin of the political class, she won, becoming the most recognizable face among a new generation of left-wing politicians seizing office.

In the run-up to 2020, so much lefty energy was coursing through the Democratic electorate that almost every Democratic candidate for the presidential nomination claimed to support Medicare for All (with Biden being a notable exception). “Warren entered the race expecting to take back the mantle of progressive warrior from Sanders,” Green writes, but in this respect she failed. Sanders emerged from the first primaries as the clear vote-leader, yet, once again, Warren did not endorse him. Several high-profile left-wing political organizations split over whom to support (DSA unsurprisingly went to Sanders, while the Working Families Party controversially supported Warren), even as the centrist candidates united behind Joe Biden (assisted by some “behind-the-scenes cajoling from Barack Obama”). The establishment Democrat won out in the end, but, concludes Green, his party is still “at the beginning of a new era,” divorced or at least distanced from neoliberalism, although the era’s contours remain “largely undefined.”

If that capsule summary of The Rebels makes it seem as if Elizabeth Warren is its protagonist, with Sanders—and, to an even smaller extent, Ocasio-Cortez—as mere supporting players in spite of their titular placement, that’s basically right. In fact, not only does Green spend the most space on Warren, he unreservedly credits her as the originary leader of the political left. She was “insurrectionary,” general of an “advancing army,” possessed of an “ability to spread a message in ways that nobody had thought of before.” She “wanted to spark a rebellion,” so she “established a populist beachhead within Democratic politics” and ultimately “sparked a national movement.” Sanders, meanwhile, does not enter the narrative until well past the halfway point, and Green devotes to Ocasio-Cortez just one (admittedly very good) chapter.

Warren’s influence on modern Democratic politics—from a renewed focus on income inequality to a renaissance of Brandeisian antitrust enforcement—is undeniable. Yet Green overstates her supposedly singular importance to the modern political left. For instance, would Warren’s populist message have caught on without Occupy Wall Street, which made the rapacity of capitalism an unignorable political issue but which barely merits a mention in The Rebels until three-quarters of the way into the book, in context Green provides to explain the rise of Ocasio-Cortez? Would Occupy, in turn, have led thousands across the country to camp out in the cold and rain without a core of savvy organizers who had cut their teeth in antiwar protests and the movement against neoliberal trade policies? Earlier contestations “by the activist left” too do not meaningfully enter Green’s narrative until page 231.

Further, Warren appears to emerge sui generis from the Democratic political class. Before Warren, Green writes, “there was no populist wing of the party to hold a president to account for his campaign promises and press the cause.” This overlooks generations of insurgent struggles, most notably the 1984 and 1988 primary campaigns of Jesse Jackson, who is mentioned just once in The Rebels. Yet, as the journalist Ryan Grim notes on just the second page of his own new account of the political left, The Squad: AOC and the Hope of a Political Revolution, Jackson’s “Rainbow Coalition” came “shockingly close” to winning the nomination and, in fact, inspired then-Mayor Bernie Sanders of Burlington to lead an effort to deliver Vermont’s delegates to Jackson.

This is not to suggest that Green’s account is ahistorical or devoid of context. In fact, he devotes several chapters to the Democratic Party’s slow capture by the financial class in a chronology going back to the 1970s, ably covering the devastating consequences, tracing much of the same ground that Grim himself did in his earlier book, We’ve Got People: From Jesse Jackson to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the End of Big Money and the Rise of a Movement. And, remarkably, while Rahm Emmanuel was the villain of Grim’s first book and conservative Democratic Congressman Joshua Gottheimer is the foil of his second, the unambiguous villain of The Rebels is Barack Obama himself.

For a Bloomberg reporter publishing with a major trade press, Green is unusually and convincingly damning in his account of Obama. He was an “inexperienced” and “malleable” president who “coddled Wall Street” and embraced a “politically poisonous” plan to bail out the financial sector at the expense of most Americans. He was not “invested in … reversing the growing inequality,” and he “didn’t have the nerve” to appoint Warren to run the CFPB. The rise of left populism, Green suggests, was as much a backlash to Obama’s banker-led economic approach as it was a response to any other factor.

Still, despite Green’s clear-eyed analysis of the role of big money in decades of Democratic politics (and, especially, in the Obama administration), he largely overlooks the broader context of the left itself. The campaigns of Jesse Jackson are far from the only omissions. The Black Lives Matter movement, the Fight for Fifteen, the teacher strikes that spread from West Virginia to Chicago and beyond—all of these provided vital training and primed the electorate to support candidates like Warren, Sanders, and Ocasio-Cortez, but none receive more than passing mentions from Green. At no point does he consider the role of the internet—chatrooms, Reddit, Tumblr, Twitter, more recently Tiktok and Twitch—in radicalizing a great many who had previously been alienated from politics. The “dirtbag left”—a loose collection of stridently anti-liberal writers and critics, perhaps most associated with the podcast Chapo Trap House—exerted a marked influence in the mid-2010s, providing an entrée to leftism for those who might eschew a more rarefied vocabulary. Yet the role of such electronic exchanges in providing the tinder for populist politicians to ignite is likewise disregarded.

To the extent Green has a thesis, it is that the 2020 Democratic primary represented some manner of repudiation “of a populist, left-wing politics,” even as that movement undeniably “shaped the core ideas of American politics and governance in 2020” and beyond. This is surely true; it is also hardly an original insight. In the book’s epilogue, Green chides the Democratic Party for writing off “working-class voters,” especially in rural states, opining that the Democrats’ best chance of success would be a focus on “economic issues.” This is not shocking stuff; indeed, it has been the party’s own self-diagnosis for almost a decade.

The question for the party’s leaders—especially those on its left flank—is what kind of economic focus is most likely to materially improve so many lives that it results (theoretically, hopefully) in durable electoral deliverance? The post-2008 left turn in politics contained multiple, contradictory approaches—a fact acknowledged but under-explored by Green. Activists and theorists differed sharply in the extent to which they saw the prevailing economic order as salvageable. To a degree, these disagreements can be summed up in the differences between Warren and Sanders, with the former embodying a reformist impulse and the latter describing himself as a revolutionary while promoting a straightforwardly democratic socialist order. In the primary, Sanders sought the complete elimination of private health insurance, while Warren did not (at least not for several years); Sanders promoted an (admittedly fuzzy) vision of greater worker ownership and governance, while Warren focused on making markets fairer and less monopolistic.

Since 2020, ideas from both camps have filtered up through the system. Grim, the Washington, D.C., bureau chief for The Intercept, concludes The Squad by noting that the Biden administration had significantly co-opted the left’s ideas, even if the establishment was using a different vocabulary. Yet the odds of a leftist takeover of the Democratic Party or the organs of government remain slim. Electoral engagement is vital, but many on the left have begun to prioritize more direct forms of political engagement.

Which is why, in the end, Green’s focus on elected officials limits his analysis. The “rebels” most likely to bring about the most transformative change may well not be those running for national office but, instead, the ones organizing workplaces and communities. “In the broadest terms, there are only two ways to reverse our poisonous level of inequality,” writes Hamilton Nolan in his book The Hammer: Power, Inequality, and the Struggle for the Soul of Labor, out in February. The first is for the government to do it—to tax the rich and redistribute their spoils—which explains the need to continue contesting elections, at all levels. Yet Nolan is skeptical of the likelihood of success. “The other way to fix inequality is for working people, who make up the vast majority of the population, to increase their own power so that they can reclaim their rightful share of the nation’s wealth,” he continues. “The only mechanism for doing this is organized labor.” Unions, he concludes—almost entirely absent from Green’s account—are “the single most important tool that exists to fix our single most important problem.”

Recently, the United Auto Workers—having just completed a successful strike campaign—invited other unions to align their contracts to expire on the same day in 2028, raising the intriguing prospect of a general strike in a presidential election year. Tactics like these gesture at a strain of labor radicalism and a willingness to confront Democratic leaders (notably, the UAW spent months extracting concessions before endorsing Biden, and other unions have continued to hold out) that bodes well for the kind of movement Nolan envisions. Indeed, wildcat strikes have been proliferating in recent years, indicating an appetite on the part of workers for seizing power outside of the sanctioned channels of union engagement. Workers cannot afford—and are increasingly unwilling—to wait for the political branches to catch up.

The fight for protective laws (eight-hour workdays, health and safety standards) has rightly been at the heart of the labor movement for decades, revealing the inextricability of union contestation from democratic institutions. Yet in an age when the right has so successfully co-opted so much of the government (more than a quarter of federal judges are Trump appointees and anti-union laws have passed in dozens of states), “organizing people as workers, not as voters”—to borrow Nolan’s words—presents the clearest path toward a new American politics.