The suggestion that Beloved, Toni Morrison’s acclaimed novel about slavery and its afterlives, is also a parable about the publishing industry would be bizarre, even offensive—if, that is, Morrison herself hadn’t explicitly suggested it. For years, Morrison had felt not merely penned in by her career as an editor at the publishing giant Random House; she had felt indentured, “held in contempt—to be played with when our masters are pleased, to be dismissed when they are not,” as she declared in a speech six years before publishing Beloved. Upon leaving her job at Random House to focus on writing full-time, she felt “free in a way I had never been, ever.… Enter Beloved.” It was, she continued in the novel’s preface, “the shock of liberation”—liberation from the world of corporate publishing—“that drew my thoughts to what ‘free’ could mean.” In the novel itself, Morrison has Baby Suggs, the protagonist’s mother, describe freedom from slavery in strikingly similar terms.

In despairing of the modern publishing industry, even comparing it to bondage, Morrison was far from alone. Indeed, as Dan Sinykin, an assistant professor of English at Emory University, argues in his revelatory new book, Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature, the increasing consolidation and corporatization of the publishing industry—a process Sinykin calls “conglomeration”—profoundly changed not merely the way novels were published but also the content of those novels. As publishers grew far larger—and ever more concerned with the bottom line—the lives of editors and authors transformed. More than ever before, they became cogs in a corporate machine, responsible for growth and returns on investment, necessarily responsive to the whims and demands of capital—and these pressures increasingly showed up in their output.

It’s a compelling thesis, albeit one that fits easily into a fast-growing literature on the forces shaping the art and media we consume. A decade ago, the critic Mark McGurl argued that the postwar relocation of American fiction writing to the campus—and especially to university creative writing programs—resulted in novels that follow now-familiar rules (show, don’t tell; write from your experience, etc.). Another influential critic, James English, pointed to the rise of an “economy of prestige”—and especially to the Booker and Pulitzer prizes—to explain the reputational ascendancy of certain genres (e.g., historical fiction) and those genres’ consequent scarcity on bestseller lists. More recently, McGurl reentered the fray to assert that the behemoth of all behemoths—Amazon—has single-handedly reshaped contemporary fiction, and still another scholar, Laura McGrath, has shone a light on the significant role played by literary agents in determining the boundaries of what is acceptable and what is marketable for the modern novelist.

Nonetheless, Big Fiction is a fresh intervention, principally due to the richness of the context Sinykin provides and the impressively broad array of evidence he marshals. In his first book, American Literature and the Long Downturn, Sinykin drew on archival material and close reading to argue that the distinct economic miseries of the last half-century—deindustrialization, deregulation, the decimation of organized labor, and widening inequality—led a great many late-twentieth-century American novelists to turn to apocalyptic fiction, imagining escape or salvation in the form of “total annihilation.” Now, wielding many of the same analytical tools, Sinykin retells that same story—but with a larger cast of characters. The same economic forces that led authors to write about the end of the world led to the corporatization of publishing, which in turn compelled authors to turn inward, to obsess over self-reflexive concerns, to create stories of individuals struggling against the end of their world.

Before the 1960s, U.S. publishing was a family affair. Small, privately held “houses” (as they’re still anachronistically called) decided what to acquire based mainly on their relationships and references. If a favored author didn’t sell, oh well, an editor might sigh, hopefully, he (and it was usually a “he,” almost always a white “he”) would do better next time. While mass-market paperback publishers brought “genre” fiction (Westerns, mysteries, romance) to the masses, the houses strove to put out literary fiction (more challenging, more aesthetically interesting, or so the prevailing wisdom dictated).

Then everything changed. In 1960, the newspaper Times Mirror Company purchased the mass-market publisher New American Library, inaugurating what Sinykin calls “the conglomerate era.” That same year, Random House went public and, flush with newfound capital, acquired Knopf and, a year later, Pantheon. Conglomeration spread rapidly, with well-capitalized behemoths gobbling up mass-market houses and old family-run firms with equal fervor. Over the next decade and a half, the electronics company Radio Corporation of America acquired Random House, a Canadian communications firm nabbed Macmillan, the Italian conglomerate that owned Fiat swallowed Bantam, and Gulf + Western bought Simon & Schuster. Ultimately, conglomeration consolidated more and more imprints under single roofs, with the German conglomerate Bertelsmann seizing Doubleday in 1986, Random House in 1998, and Penguin (via a merger) in 2013.

The economic downturns of the late twentieth century, starting in the 1970s, did nothing to halt the rise of conglomerate publishing; in fact, they accelerated the process. Management consultants arrived, and they contributed to a fundamental shift in the way U.S. publishers did business. Editors, who had previously enjoyed considerable freedom and made decisions based on their personal preferences and gut instincts, now had to do so by reference to a balance sheet; they had to prove that each title they wished to procure would be a moneymaker. “Editors,” Toni Morrison claimed in her 1981 speech, “are now judged by the profitability of what they acquire rather than by what they acquire.” This led editors to take fewer risks and go out on fewer limbs; it led literary novelists to adopt the techniques of their lower-brow counterparts, turning to what sold.

Sinykin points to the illustrative example of Cormac McCarthy, who was lucky enough to start publishing under the old regime. For 28 years, starting in the mid-1960s, he put out dense, difficult novels with Random House without ever selling well enough to get a single royalty check. When his old-school editor retired in 1987, McCarthy—aware he was navigating a new world—hired a literary agent for the first time. Fortunately for him, he piqued the interest of rising super-agent Amanda “Binky” Urban, who moved him over to Knopf, where his next novel would be overseen by editor Sonny Mehta and others, the new generation. Relocated to a new imprint, with a new editor and an agent, McCarthy changed his style; he abandoned his abstract plots and instead wrote a Western, the story of a young cowboy mourning the death of his world, embracing many of the techniques of genre novelists as he did so. That novel, All the Pretty Horses, soared to the bestseller lists upon its publication in 1992; it sold 100,000 copies and was adapted into a blockbuster movie. Cormac McCarthy became and remained a star.

Departing from previous chroniclers, Sinykin argues that his career should properly be seen as divided “by refuge from, and then participation in, the conglomerate era,” culminating with his “Oprah Book Club-endorsed, postapocalyptic mega-bestseller,” The Road in 2007. “Conglomeration made McCarthy middlebrow.” This was a success story, and many literary authors did as McCarthy had and embraced genre conventions, from A.S. Byatt in Possession (romance) to Denis Johnson in The Stars at Noon (spy thriller) to Colson Whitehead in Zone One (zombie apocalypse). “The literati began to rethink its snobbery,” in Sinykin’s telling. Yet many writers were far from sanguine as their landscape transformed. As Sinykin narrates, novelists began responding to the new economics of publishing in ways that betrayed their fundamental status anxiety.

In the 1970s, mass-distribution wholesalers replaced book publishers as the main suppliers of books to bookstores; in the 1980s, chain bookstores—first suburban outposts like B. Dalton and Waldenbooks, later superstores like Borders and Barnes & Noble—exploded across the land. Both developments incentivized publishers focusing on brand-name authors and reliable, formulaic works—books they knew would appeal to profit-driven entities that were less amenable to obscure or experimental works and, importantly, bought in bulk. Conglomerate publishers (like Random House) bought up the mass-market houses (Bantam and Dell, in the case of Random House) and, more broadly, began putting out more of the very genres—bodice-rippers, detective stories, horror—that the former had popularized. Conglomerate publishers also built up robust publicity and marketing departments. The production of new novels ceased to be “the work of a relatively autonomous author-editor duo,” Sinykin writes.

In his telling, authors began exorcising their anxieties in their novels. Sinykin’s first sustained case study is E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime, the bestselling novel of 1975, a parable about trying (and failing) to retain artistic integrity in an increasingly mechanized age. His next is Danielle Steel, a writer of unremunerative literary novels eventually transformed by her corporate publisher into a ubiquitous bestseller of anodyne romances—and whose first megahit was The Promise (1978), which has its artist-heroine literally transformed by a powerful man (her plastic surgeon) but nonetheless reclaim her agency by continuing to express herself authentically in art.

Building on the work of other scholars, Sinykin argues that autofiction—a neurotic, genre-blending autobiography and fiction—allowed male authors like Norman Mailer, John Barth, and Kurt Vonnegut to “exhibit and counter their fear of losing power” and female authors like Renata Adler, Elizabeth Hardwick, and Alison Lurie to “advertise constraints imposed on them by patriarchy in publishing.” Both turns reflected the particular precarity of fiction writing in the conglomerate age. In fact, many recent works of autofiction—including novels by Sally Rooney, Ben Lerner, Rachel Cusk, Karl Ove Knausgaard, and others—are explicitly about the challenges of navigating the publishing industry. “Autofiction projects the fantasy of victory over the systems that threaten to interfere in the cultivation of the expressive self,” Sinykin writes, “which is why it is so useful in the conglomerate era.”

Anxiety shaped even novels that reached the very peak of the bestseller lists. As publishing corporatized, it was simply financial common sense for houses to throw extraordinary resources, and a disproportionate share of attention, at ultra-bestsellers. Between 1986 and 1996, Sinykin notes, 63 of the 100 bestselling books in the country were written by just six people: Tom Clancy, Michael Crichton, John Grisham, Stephen King, Dean Koontz, and Danielle Steel. Astonishingly, five of those six continue to dominate bestseller lists to this day. (No doubt Clancy would too, had he not died in 2013.) Yet several of these brand-name authors stressed over their status as marquees, as popular—not prestigious—moneymakers. This anxiety, Sinykin argues, can be seen in Stephen King’s Misery, in which an author is literally held hostage and forced to write by a deranged superfan.

Of course, it would be easy to object to Sinykin’s close readings on the grounds that works of fiction yield many interpretations, and a scholar looking to confirm his hypothesis will undoubtedly be able to find a great number of amenable titles. In his first book, Sinykin noted how David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest “reveals addiction as a general condition within the debt economy,” where “the consumer becomes the addict.” Now, in his second, he glosses the novel as “an allegory for the conglomerate publishing industry,” a story about a “heroic artist hoping to cut through a culture overwhelmed by media conglomerates.” Yet Sinykin’s interpretations are persuasive in large part because many are supported with archival evidence and interviews. He makes particularly convincing use of Random House Records, which chart the quintessential conglomerate’s metamorphosis and its editors’ roles as stewards of the brave new world of commercial publishing. The shockingly sexist correspondence of editor Bennett Cerf in the 1960s helps to explain the press’s marginalization of female authors—and those authors’ subsequent turns to “self-reflexive novels”—while the letters of editor Joe Fox reveal a sovereign struggling mightily to maintain editorial control over publicity and marketing even as conglomeration gradually diffused his authority in the name of the almighty dollar.

Some publishing houses, however, have always been less commercial: the avant-garde houses like New Directions, the small presses like Coffee House, and the university presses. Yet, according to Sinykin, even the output of these nonprofit publishers has been shaped by conglomeration—that is, by their opposition to its demands.

Nonprofit publishers can trace their origins to the proliferation of cheap mimeograph technology in the 1950s, a predecessor to today’s photocopiers. Suddenly, a few guys in a house somewhere could produce their own books. Several now-eminent nonprofit publishers (Graywolf, Copper Canyon) emerged from the seaside town of Port Townsend, Washington, which had a small but influential writing scene. Others sprang up in Chicago, Iowa City, and Houston. Eventually, Minnesota’s Twin Cities emerged as a hub of nonprofit publishing, the burgeoning houses attracted by the availability of local philanthropic and government funding. Coffee House and Milkweed grew from Minnesota soil; Graywolf moved there in the 1980s.

For four decades, in Sinykin’s telling, nonprofit publishers have defined themselves against conglomerate publishers, putting out consciously literary fiction to counter the oversaturated commercialism of the big houses, putting out transgressive works by numerous authors of color to counter the overwhelming whiteness of trade imprints. Unlike the few “multicultural” works put out by conglomerate publishers (see the oeuvres of Amy Tan, Sandra Cisneros, and Louise Erdrich), Sinykin argues that nonprofit authors like Percival Everett and Karen Tei Yamashita “deployed irony to satirize multiculturalism itself,” implicitly criticizing “mainstream representations of race.” At the conglomerates, by contrast, “writers of color tended to perform the authentication of identity while sometimes searching for strategies to evade the quietist reading practices of white liberals.”

In short, many of the most celebrated, most studied authors of the late twentieth century were “industrial writers,” Sinykin argues, either writing within or against conglomeration. “Until we recognize that, we have misread six decades and more of U.S. fiction.”

Sinykin’s final chapter looks at the exception that proves the rule. If conglomerates and nonprofits “form an organic whole: lash and backlash,” he writes, with the business models and literary styles of each resisting yet feeding off the other, W.W. Norton operates outside of this symbiotic system. It is, Sinykin writes, “that rarest of birds: a large independent house that publishes literary fiction and poetry. It is, in fact, the only one left.” According to Sinykin, Norton has accomplished this unexpected feat for two reasons. First, it is employee-owned, giving its editors more autonomy than their counterparts at other big presses. Second, its profitable college division effectively subsidizes its fierce editorial independence.

The fiction put out by Norton is different from that produced by either conglomerate houses or nonprofit houses. It is one of the few publishers to still release so-called “mid-list” titles, those that aim to sell but aren’t expected to break the bank; it publishes translations, out-of-print classics, and graphic novels (a trend where Norton was “on the bleeding edge”); it has put out experimental, singular novels, like the very gay, oddly utopian Fight Club. Norton also produces works of literary genre fiction, but different from the works of Cormac McCarthy or Colson Whitehead. While those authors, avatars of conglomerate publishing, imported genre techniques into literary fiction, Norton’s authors—including Walter Mosley and Patrick O’Brian—imported literary techniques into genre fiction.

Yet even the holdouts from the conglomeration are not immune to broader economic trends, and Sinykin ends this chapter on an ominous note: In 2008, the financial crisis and the rise of Amazon (and the release of its Kindle) accelerated the neoliberalization of publishing. After years of resistance, Norton finally built a significant marketing department.

Still, Sinykin concludes Big Fiction by noting that it took only “a few hiccupping years” for the conglomerate publishers to learn to accommodate Amazon, ebooks, and audiobooks. “Rather than remaking the industry, 2008 intensified the conglomerate era.” The biggest publishers “doubled down” on autofiction, literary genre fiction, and more recently multicultural fiction—and flourished. The sales of ebooks, which were supposed to kill off paper once and for all, plateaued more than a decade ago; digital audiobooks, rather than supplanting other media, instead became a deviously effective antidote to the 2008 financial crisis: a way to participate in “contemporary grind culture” and still read, squeezing snippets of novels into a commute, workout, or household chore. For authors, social media and the online literary ecosystem simply meant they had to do even more work, now taking on marketing and publicity efforts for their own books, as a form of “promotional entrepreneurialism” became de rigueur. Perhaps the only substantive change to the output of conglomerate publishers in the last decade and a half has been the profusion of young adult fiction, a development driven by ardent online fandoms.

At the same time, however, Amazon, TikTok, Wattpad, Archive of Our Own, and other digital fora have led many, many authors far outside literary metropoles like New York or Minneapolis to experiment with fiction in strange and thrilling ways, from the copyright-less collective authorship of fan fiction to the explosion of hyper-niche genre works distributed by Amazon’s Kindle Directing Publishing and similar platforms. A very few authors have made the leap from the electronic hinterlands to the Big Five—including E.L. James, Colleen Hoover, and Andy Weir—but the great majority never will.

Big Fiction is sharply written and sharply argued, part of a wave of cutting-edge works of literary history put out by Columbia University Press. Wisely, Sinykin “defers judgment about whether conglomeration was good or bad,” instead charting its consequences.

At this point, the question of whether conglomeration was good or bad seems largely beside the point. Artists adapt. Artists have always been subject to the whims of the wealthy. Yet the same economic forces that led to conglomeration are undeniably immiserating artists today. More authors than ever before have access to an audience and the means of literary production; fewer authors than in decades past are able to support themselves through writing alone. Publishing houses continue to consolidate—and one of the biggest, Simon & Schuster, was just sold to a private equity firm, part of an industry infamous for gutting local newspapers. Meanwhile, entry-level employees at those publishing houses are paid so abominably that many have recently quit en masse.

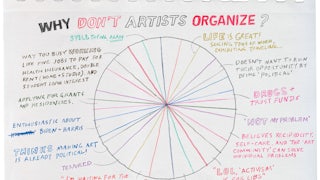

Where do writers, editors, and for that matter critics go from here? How do we make art under these conditions? One’s answer to such questions is inextricable from one’s politics more broadly, from one’s view of what we owe each other, whether the rich deserve their spoils, and the extent to which workers should determine the course of their lives. W.W. Norton’s collective ownership provides one glimmer of a possible artistic future. So too does the recent strike of HarperCollins workers for fair wages, the rise of artists’ and freelancers’ unions, the flowering of writers’ collectives during the pandemic. If, as Sinykin argues, the ascent of conglomerate publishing relocated power “out of the hands of the author and the editor and into a great many hands,” as the ranks of publicists, marketers, and agents swelled, perhaps the possibility of solidarity remains, of strength in the growing numbers of collaborative workers.