In December 1970, on a visit to Warsaw, Willie Brandt, chancellor of West Germany, came to the site of the Warsaw Ghetto. Brandt sank to his knees and bowed his head. At the time, the gesture was controversial in Germany. Brandt, who had himself fought the Nazis, seemed to be asking forgiveness on behalf of his fellow Germans. The vast majority of them had not taken part in the crimes of the Nazis. They had been too young or not yet born or merely bystanders.

Looking back on that gesture today, it marks the beginning of a period in which most Germans came to accept political responsibility for the crimes committed by other Germans. That acceptance has not only transformed Germany. It has also transformed the way that Germany is regarded in countries that were the principal victims of the crimes of the Nazis.

As Gary Bass points out in Judgment at Tokyo, there was never a moment in which a Japanese leader made a comparable gesture. In important respects, Japan has also been transformed since the end of World War II. Today’s pacifist Japan is a far cry from the militarist state of an earlier era. But few if any Japanese leaders in the postwar era have seemed to feel that they need to ask for forgiveness on behalf of their fellow citizens. Most of those who have served in the post of prime minister of Japan have paid publicized visits to the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo in tribute to Japan’s war dead, where the names, origins, birth dates, and places of death of more than a thousand convicted war criminals are remembered. Denunciations by the governments of China, South Korea, and other countries that count themselves among the victims of Japanese war crimes have not deterred those visits.

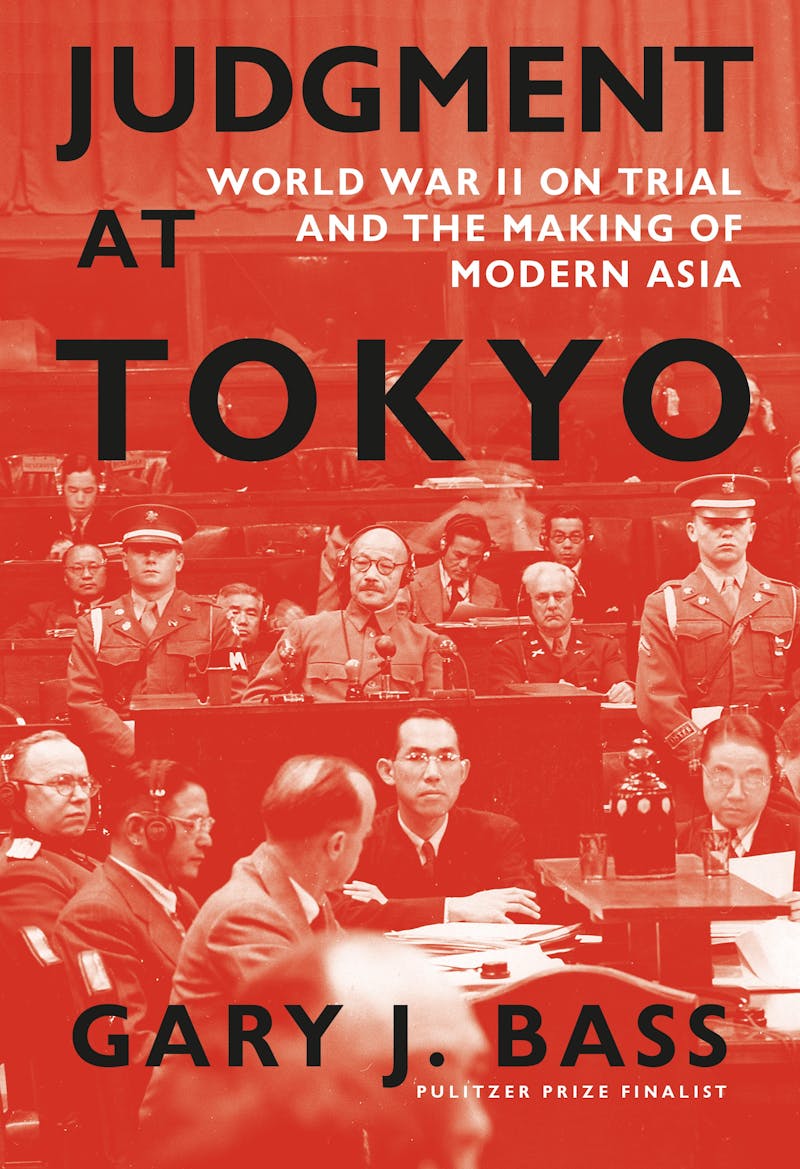

A professor of international relations at Princeton, Gary Bass has written extensively about aspects of twentieth-century history in which governments encounter important policy choices in dealing with humanitarian disasters and the commission of atrocities. His most recent previous book, The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide, dealt with the 1971 war for the independence of Bangladesh. It was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in general nonfiction. His new book, Judgment at Tokyo, is the definitive scholarly account of that proceeding—which lasted from April 1946 to November 1948—and its historical and legal context and a compelling work on the politics of East Asia.

Many Americans know about Japanese war crimes during World War II that victimized captured soldiers from Western countries, as depicted in the classic 1957 British film The Bridge on the River Kwai. Prisoners of war from countries like the United States and Britain generally suffered far worse mistreatment from Japanese captors than from Nazi captors. Unlike Germany, Japan had not ratified the 1929 Geneva Conventions, which prohibited such practices. Also, of course, Japan expected its own troops never to surrender. They were to fight to the death. As it was thought that a Japanese combatant should never be taken prisoner, there was no reason to spare enemy captives as a way to help ensure reciprocal practices by Western forces.

Less well known in this country are the great cruelties practiced by Japanese forces in other countries in Asia. There were no equivalents of the Nazi death camps, but Japanese soldiers routinely raped, tortured, and murdered civilians in China, the Philippines, Korea, Burma, Indonesia, and other Asian countries. The “Rape of Nanking,” which began in December 1937 with Japan’s conquest of the city, which was then the Chinese capital, lasted for a period of several months. Up to 300,000 Chinese were murdered, and an estimated 20,000 rapes took place in the first month of the Japanese occupation of the city.

On a visit to contemporary Nanjing in 2005, I went to the very large museum, established in 1985, that commemorates that episode. In one respect, there was not much to see. My recollection is that most of the exhibits I saw were framed copies of faded photos and bulletins from that era. In another respect, however, there was a great deal to see. The crowd in the museum and the lines waiting to get in were the largest I can ever remember seeing at a museum or memorial site anywhere in the world, and it was evident that the visitors considered their visit to be a solemn occasion.

In China, Korea, and other Asian countries, many thousands of young women were forced into sexual slavery for Japanese forces. On a visit to Indonesia about 20 years ago, I met with a group of these so-called “comfort women,” many of whom were then in their seventies and eighties, in the offices of a lawyer who was suing the Japanese government for compensation for them. Many were teenagers when their enslavement took place. I learned that they had not been able to bring suit earlier because, during the 32 years that the dictator Suharto was in power in Indonesia, he had not wanted to jeopardize Japanese investments in his country.

Another Japanese war crime that Bass discusses involved what was known as “Unit 731.” This was a top secret program of the Japanese army, located in northern China, that conducted human experiments for bacteriological warfare. These apparently included spraying a war zone in China with materials intended to cause plague, cholera, and anthrax, leading to a large but unknown number of deaths. The U.S. and the Soviet Union suppressed information about Unit 731 and the thousands of Chinese who died in these experiments because they wanted the information that had been produced by this research. It was never discussed at the Tokyo war crimes tribunal.

The tribunal was established under the authority of General Douglas MacArthur, the commander of the Allied Powers in occupied Japan. MacArthur issued the charter under which the tribunal operated. Like the Nuremberg Tribunal, it was to deal with three kinds of crimes: crimes against peace, or aggressive war, known in Tokyo as Class A crimes; traditional war crimes, such as the mistreatment of prisoners of war, as specified in international treaties, known in Tokyo as Class B crimes; and crimes against humanity, known in Tokyo as Class C crimes. The contention that “aggressive war” should be considered a crime was very controversial. The main argument was that the Kellogg-Briand pact of 1928, which Japan had signed, had outlawed war, though it never stated that launching a war was a crime. Though the concept of crimes against humanity, which refers to crimes committed on a large scale that involve gross abuses of human rights such as murder, torture, and enslavement, has deep roots, they were not then defined in any international treaty. Yet many of the convictions by the Nuremberg Tribunal had been for crimes against humanity.

MacArthur himself was mainly interested in Class A crimes. Above all, he saw the tribunal as a means of retribution against those responsible for the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Another interest of MacArthur played an important role in the trial: He was intent on avoiding the indictment of Emperor Hirohito. To administer occupied Japan successfully and to bring about the transformation of the country from a militarist autocracy to a peace-loving democracy, MacArthur needed Hirohito.

Under MacArthur’s tutelage, Hirohito became a constitutional monarch. MacArthur, with the collaboration of the chief prosecutor at Tokyo, Joseph Keenan, an American, tried to shield Hirohito—not always successfully—against testimony that would show that he could have prevented many of the crimes for which others, like Prime Minister Tojo Hideki, were convicted by the tribunal and sentenced to death. All 25 defendants in the Tokyo trial were convicted of at least one of the categories of crime that the tribunal considered, and seven of them were sentenced to death. They had all been convicted of Class A crimes. By way of comparison, of the 22 defendants at Nuremberg in the trial of the top Nazi leaders, 12 were sentenced to death (including Martin Bormann, who was tried in absentia but actually committed suicide before the trial and whose remains were not definitively identified until many years later), and three were acquitted. At Tokyo, the shortest sentence—seven years—went to Mamoru Shigemitsu, whom Bass describes as “a comparatively blameless foreign minister.” After serving time in prison, he became foreign minister again in 1954. Another accused Class A suspect who spent time in prison became prime minister in 1957, and his grandson, Shinzo Abe (who was assassinated in 2022) eventually became Japan’s longest-serving prime minister.

As chief prosecutor, Keenan was not of the caliber of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, who played that role at the first trial at Nuremberg, nor of Telford Taylor, the chief prosecutor at subsequent Nuremberg trials. Jackson and Taylor embodied the demand for justice, combining great eloquence and legal acumen. Keenan sometimes appeared in court under the influence of his heavy drinking. Nor were all of the 11 judges from countries that fought against Japan of top quality.

A number of the judges dissented from parts of the judgment of the tribunal. One of the more learned judges, Radhabinod Pal of India, dissented from all the convictions on all charges. In essence, Judge Pal took the position that the crimes committed by the Allies against Japan vindicated Japanese military commanders and political leaders of the crimes charged against them. Judge Pal is celebrated in Japan. There is a monument to him in the Yasukuni Shrine.

Judge Pal’s dissent and the failure of Japanese political leaders to accept political responsibility for the crimes committed by Japan in its conduct of the war seem to me to reflect the perception that Japan was as much a victim of war crimes as it was the perpetrator of war crimes. The Allies had also committed great crimes against Germans and their other European enemies during World War II. These included the firebombing of cities such as Dresden and Hamburg by Britain and the U.S., the great number of rapes committed by Soviet soldiers as they made their way through Eastern Europe and through Germany to Berlin, and the rapes committed by Moroccan troops under French command in the invasion of Italy. Though these gross abuses were never discussed at Nuremberg and were never punished, they were dwarfed in significance by the revelations of the atrocities committed by the Nazis.

Moreover, the trials at Nuremberg were followed by literally thousands of trials of Nazi war criminals that have continued almost up to the present day in German courts. Those trials have both reflected German acceptance of the guilt of their fellow Germans for war crimes and, at the same time, contributed to that acceptance. They are an expression of the country’s profound sense of political responsibility for German criminality. There were never similar trials of Japanese war criminals in Japanese courts. Those trials and punishments that took place were in military tribunals convened by the Allies and in the courts of some of the countries where Japanese troops remained when the war ended.

In the war against Japan, Americans firebombed most of the country’s cities. Bass writes that President Harry Truman “repeatedly boasted about the firebombing of Tokyo and dozens of other Japanese cities.” These cities were largely made up of wooden houses, and they burned easily. Tokyo was firebombed on March 9, 1945, at a time when the outcome of the war had already been decided. Estimates of the number of those killed in that attack on Tokyo range from at least 80,000 to well over 100,000, the overwhelming majority among them civilians. One of the reasons that Hiroshima and Nagasaki were selected as the targets for the atomic bombs dropped on Japan in August 1945 was that they had not been firebombed. That made it easier for American officials to assess the damage done by nuclear weapons.

A factor that led to the American development of the atomic bomb was fear that Nazi Germany would succeed in doing so. The intent was to be able to use the bomb in Europe. The German effort failed, and the war in Europe ended before the bomb was ready for use. The fact that Japan became the only country that has suffered from the use of atomic weapons has undoubtedly played an important part in the perception by many in Japan that they were chiefly victims of the war. On the other hand, the large crowd I saw at the Nanjing Museum that commemorates the Rape of Nanking, and vast numbers of people, not only in China but throughout the countries of East Asia who suffered from Japanese criminality during World War II, continue to harbor ill will against Japan.

They are reinforced in those views every time a Japanese leader pays a visit to the Yasukuni shrine. As Gary Bass writes, “It is only by understanding the reverberations of World War II in East Asia that one can begin to make sense of the otherwise baffling spectacle of a peace-loving democracy losing the moral high ground to a nationalistic Communist dictatorship.”

Japan’s reluctance to accept political responsibility for the crimes committed by its leaders and many of its soldiers during World War II is probably a factor in its standing in contemporary world affairs. The country’s economic strength, its democratic political system, and its distinctive cultural heritage should make it a counterweight in East Asia to China. Certainly, countries such as South Korea and the Philippines could benefit from support in their dealings with the region’s increasingly assertive superpower. Yet they do not seem to look to Japan for such support. In contrast, Germany is acknowledged as a leader of the EU, and during Angela Merkel’s tenure as the country’s chancellor, she was widely acclaimed as the leader of the free world. Japan’s reluctance to accept political responsibility for its conduct during World War II casts a long shadow over its standing in Asia.