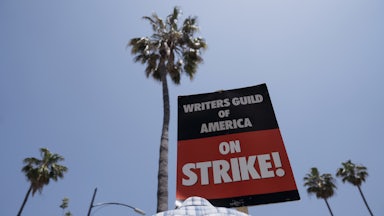

When the Writers Guild of America went on strike five months ago, the studios clearly thought they had the upper hand. They dismissed the majority of the guild’s demands without so much as a response. They taunted writers with anonymous threats about an admittedly “evil” scheme to impoverish us and drive us from our homes (a plot point so outlandish, the writers would have scrapped it). They bragged about all the cash they would save, as entertainment companies, by no longer making entertainment. And they confidently assured investors that they had nearly infinite libraries of film and television stockpiled, with one CEO insisting, “We have a lot of content that’s been produced,” and another boasting, “We’ve been planning for this … consumers really won’t notice anything for a while.”

By late summer, the CEOs were berating guild negotiators to their faces about how generous the studios’ proposals were, and leaking the details to members in a desperate (and pointless) bid to go around leadership. Actors joined the writers on strike. Stars walked off red carpets. Picket lines swelled. Polls showed overwhelming support for the strikes among the general public. The stock prices of nearly all the major entertainment companies had taken major hits by then, with Disney shares falling below $100 to a nearly nine-year low. Warner Bros.-Discovery confessed to Wall Street that it would lose $300 to $500 million due to the strikes.

And as for that limitless supply of peak television available for on-demand viewing? Two weeks after the strike began, ABC announced that it would start production on a senior citizen version of The Bachelor (no word yet on an octogenarian version of Survivor). And by September, Max had quietly imported onto its service a U.K. reality show called Naked Attraction, in which contestants vying for a date are judged solely by their naked bodies (a nightmare more chilling than anything Ari Aster could conjure).

Clearly, the studios had misjudged things. They came back to the table earlier this month. The two sides struck a tentative agreement this week. And the strike is now over as of Wednesday.

In May, when the strike began, the studios refused to share streaming data, called minimum staffing guarantees a nonstarter, and offered only an annual meeting to discuss advances in technology (like a TED Talk, but mandatory). Five months later, the tentative agreement contains unprecedented new protections against the use of artificial intelligence in scripts, a first-of-its-kind success-based formula for streaming residuals, and requirements for minimum staffing and length of employment. Guild leaders have called this agreement “exceptional.” Variety reported that “the WGA prevailed in forcing Hollywood’s largest employers to address the guild’s major priorities.” And The New York Times wrote, simply: “The Writers Guild of America got most of what it wanted.”

The lesson is clear: Strikes work.

No one ever wants to strike, and no one likes striking—especially those of us in the entertainment industry, desperate for the validation we derive from audiences who consume our work. But as the writers’ and actors’ strikes have shown, being part of a collective action—especially one as joyous, righteous, and creative as the Hollywood strikes of the summer—can be morally and spiritually invigorating. For those of us who love writing and love writers, it was deeply gratifying to stand up for a craft so often overlooked by our industry.

Withholding your labor can no doubt be painful and nerve-racking. And the bosses do everything possible to intensify that pain and instill fear. We all heard the same insidious whispers from the studio side as a possible strike approached: that a strike would be pointless and self-defeating; that the companies couldn’t afford it; that they were actually losing money; that the timing of this particular strike was especially bad; that they could wait us out for as long as it took; that they were all-powerful masters of the universe, playing three-dimensional chess, anticipating our every move; that they would actually welcome a strike as a cost-cutting measure (the companies weren’t mad, they were laughing, actually).

Never mind that eight major Hollywood CEOs collectively made over $750 million last year. Or that one executive at Roku—Roku!—made over $50 million. Or that one movie, Barbie, generated well over $1 billion in revenue. These are highly profitable companies run by lavishly compensated executives. And yet they expect that, when they plead poverty, the rest of us will believe them.

And that is why strikes are important.

A strike is clarifying. It’s a cards-on-the-table moment. When we, as workers, withhold our labor, the CEOs can no longer hide, or obfuscate, or fudge their numbers. Faced with the manifest reality that they have nothing without us, they’re forced, eventually, to come clean. The same storyline is unfolding right now in the auto industry, where thanks to the United Auto Workers strike, even The Financial Times is questioning the fact that CEOs make 300 times what their workers do, and where GM’s chief executive was recently grilled on cable news about her exorbitant salary.

My first glimpse that something extraordinary was happening this summer came in May, when I was asked to speak at a rally outside 30 Rock, where I write comedy for a show I love with friends I adore. What I encountered when I got up to the podium was staggering. More than a thousand writers, actors, and allies from across the labor movement had poured onto 49th Street. The raucous crowd included nurses, teachers, teamsters, and retail workers. Our struggle was theirs, and theirs was ours. The crisis we were facing was existential. It was their crisis too.

It was at that moment that I realized just how wrong the studio propaganda had been. We hadn’t picked the worst time for a strike; we’d picked the best time. Which is to say, any time that your bosses refuse to properly recognize your value as a worker, or offer you a litany of excuses for why you can’t have the fairness and dignity that you deserve. “We don’t have the money.” “It’s not a good time.” “Have you told your grandparents to audition for The Bachelor?”

Faced with the reality of a strike, all of those lies evaporated. Their excuses and false bravado crumbled. And much like the contestants on Naked Attraction, the companies were laid bare for all to see.

The writers won. So will the actors, and the auto workers, and anyone after us who confronts the bosses and takes up the workers’ cause. The year’s big blockbuster is the resurgence of the labor movement, and we are all in marquee roles.