Look at just about any White House event, and you’re likely to see a reference to a specific number: 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), a goal in line with meeting the Paris Agreement’s ambition to limit warming to “well below” two degrees Celsius.

A fact sheet on America’s partnership with climate-vulnerable Pacific Islands this week noted that the U.S. “will continue to work with the Pacific Islands to enhance global ambition to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius.” Speaking in Vietnam, Biden called the prospect of not avoiding 1.5 degrees Celsius “the only existential threat humanity faces even more frightening” than nuclear war. A recent Washington Post op-ed from climate envoy John Kerry warned that an expansion of coal-fired power plants “would be the death blow to the Paris climate agreement goal of limiting global warming to the critical threshold of 1.5 degrees Celsius in this century.”

A new report helps shed some light on how likely that is. The International Energy Agency’s updated Net-Zero Roadmap, released Tuesday, offers a cautiously optimistic picture of what achieving that vision might entail: tripling global renewable energy capacity; deploying $4.5 trillion a year in clean energy spending by the start of the 2030s; a 75 percent cut in energy-sector methane emissions before then. This is far from an easy proposal—emissions in advanced economies would need to drop 80 percent in the next 12 years.

The pathway described entails dramatic changes to everyday life. In order to stick to that 1.5 degree threshold, by 2030, large cities will have phased out internal combustion engine vehicles. Starting this year, no new oil and gas fields with “long lead times” would be approved, as global production starts to decline by around 2 percent annually, in line with a 25 percent reduction in global fossil fuel demand by the end of this decade.

Report authors argue that the target is still within reach—but, realistically, this is not the pathway the world is on. Between now and 2030, the IEA report also warns, investment in fossil fuel supply, power generation, and end uses is projected to be $3.6 trillion more than in the scenario described above. Though there’s been a promising expansion of solar power, fossil fuels continue to meet 82 percent of the world’s energy demand—down only 5 percent since 2000. Just three of the 50 energy transition components the IEA identifies are in line with its net-zero pathway.

The new head of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, Jim Skea—who co-chaired one of the working groups that contributed to the panel’s special report on 1.5 degrees Celsius—even said in July the world would exceed that target. “We are, I think, committed to at least some degree of overshoot,” Skea told reporters, citing the insufficient plans on offer from governments. There is no magic trigger pulled should global average temperatures exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming. This summer, the hottest on record, the world even surpassed it temporarily. “The world won’t end if it warms by more than 1.5 degrees,” Skea told the German outlet Der Spiegel, noting that it would be “a more dangerous world.”

Why do U.S. politicians insist on talking so much about a goal they’re so far off track from? In the U.S.—a country still ostensibly working toward the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold—domestic oil production is on track to reach record levels this year and next. The U.S. stands poised to become a net crude oil exporter for the first time. Methane gas exports—having only begun in earnest after 2015—are surging; just this summer, the Energy Department denied a request from green groups to establish comprehensive climate guidelines around the industry. Bloomberg reported on Thursday that the Interior Department’s forthcoming five-year guidance on offshore drilling will reportedly continue the sale of leases in the Gulf of Mexico, having rejected calls to block auctions.

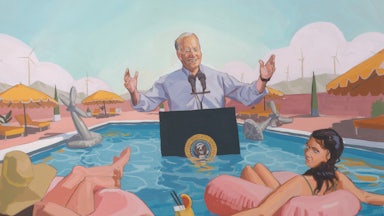

“People continue to plan and build and burn unmitigated, unabated fossil fuel,” Kerry barked during a breakfast meeting at the U.N. climate summit last week, referring to new coal production in Asia. The U.S., meanwhile, remains among the world’s top five coal producers. It’s also projected to be responsible for more than a third of global oil and gas expansion planned to happen before 2030. It’s a surreal feeling, watching top Biden officials stress the importance of reaching a target that the White House itself seems determined to undermine.

There’s no obvious alternative to the White House continuing to restate a target arrived at for very good reasons, but which the U.S. government seems plainly unwilling to align itself with in the short term. Plenty of earnest, talented, and anonymous White House staffers are working diligently to try to get as close as possible, of course. There are certainly worse things than having a hugely ambitious goal to aim for against the odds. And the 1.5 degrees Celsius target remains significant to try and convince voters that the Biden administration is doing all it can on climate change. At the top, though, maybe officials shouldn’t boast about their progress toward a 1.5 degrees Celsius pathway with one hand and green-light a raft of dangerous drilling and fossil fuel infrastructure with the other.