Was it magic or

magnets that made the machine move? Perhaps a divine spark or a mischievous spirit?

For 60 years European high society marveled at a device called the

Mechanical Turk, a life-sized mannequin in mock-oriental robes attached to a

box crammed with brass gears. The machine, it seemed, could play chess without

any human help. Maria Theresa was charmed by the contraption; Ben Franklin lost

a game to it; Napoleon Bonaparte tried to cheat the Turk with illegal moves,

yet every time, the puppet picked up the pieces and put them back where they

started with a slow shake of its wooden head.

The trick was that inside the Turk there was a chess grand master, operating by candlelight. The intelligent machine was an illusion. But the dream of automation inspired Edmund Cartwright, a minor English poet and clergyman. He caught the Turk’s performance in London in 1784 and thought its principles could be applied to the cloth trade. If an automaton—or what looked like one, anyway—could play chess then surely it could weave a warp thread. Gadgets to spin raw cotton and wool into ropes of yarn had existed for hundreds of years, yet the process of transforming that yarn into fabric was still done slowly in the homes and small workshops of trained artisans, a cottage industry (in the original sense) that dominated the North and Midlands of England. If Cartwright could design something powered by a watermill or steam engine, “splendid fortunes” would follow.

Cartwright knew nothing about clothmaking, and whenever he asked the workers for help with his design, they spat at his feet. The weavers who sat rhythmically pumping their hand looms, the croppers who cut and finished the cloth, the stockingers who knitted fine lace and hose knew what Cartwright’s “power loom” would mean: the overturning of their lives, the ruin of their families, and the destruction of all that was thought to be stable and secure in the world.

It took more than a decade before Cartwright’s power loom was reliable, and as soon as the machine arrived in a cloth town, the weavers would break it apart with hammers and set fire to the workshop. The more power looms appeared, the more the weavers resisted. To hide their identities, to appear like a limitless unstoppable force, these workers took their name from a legendary folk hero: Ned Ludd, a young apprentice said to have rebelled against the drudgery of his work and the vicious discipline of his master, broken the looms, and fled for the forest.

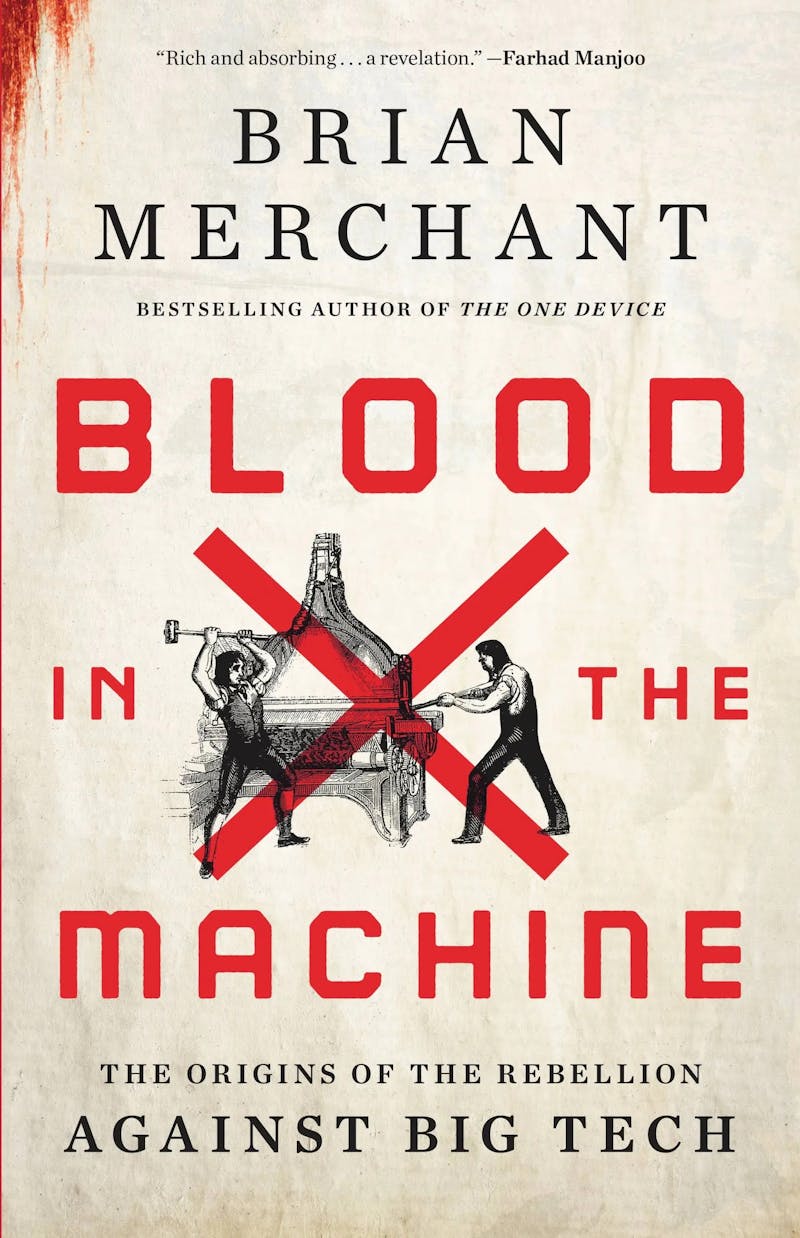

Like so many other terms shorn of their older and more dangerous meanings, the word “Luddite” long ago lost its association with a collective, militant struggle and became both an individual attitude and a slur: a word for a simpleton who despises and fears technology because they don’t understand it. Brian Merchant, a tech columnist for the Los Angeles Times, hopes to correct this distortion in his new book Blood in the Machine. “The Luddites understood technology all too well; they didn’t hate it, but rather the way it was used against them,” Merchant explains. They saw “devices that would degrade their working conditions or harm their ability to earn a living” as “a moral violation.”

A blend of pacy narrative history and contemporary reportage, Blood in the Machine sees a fresh relevance in the struggles of these misunderstood rebels. The weavers’ combat against “machinery hurtful to commonality” was, in Merchant’s view, the earliest resistance to the destructive tactics of “big tech.” “Move fast, break things” operators like Musk, Thiel, and Bezos are “using a new version of the same concept” as the earliest factory owners, when they wield technology to upset established methods of production. Just as the clothworkers were the first to experience the full force of the Industrial Revolution, so we too find ourselves in a similar position at the (alleged) dawn of a Second Industrial Revolution—in an upheaval driven not by the brute force of the iron smelter, the railway locomotive, and the power loom but the more subtle advances of robotics, microchips, and artificial intelligence.

The Luddites were

smarter, better organized, more popular, and more violent than the limp

caricature handed down to us might imply. Stretching from Nottingham to York to

Manchester, the Luddites’ machine-breaking campaign at its height in 1811 and

1812 looked very much like an industrial civil war. Each regional clique had its

own character and methods, yet they all pursued a common goal and were,

Merchant argues, “organized, strategic, and intentional in their displays of

power.”

In their silent midnight raids, their faces smeared with coal soot, Luddites smashed only looms and machines that threatened their livelihoods directly and left others alone. They also had a sense of humor. During a raid on the house of a master cloth dresser named Samuel Swallow, the West Riding Luddites barged in, took sledges to his machines, trashed his workshop, threatened to blow the place up if he ever introduced a machine again, and as they left, suggested he lock the door behind him. As their operations became larger and more complex—culminating in the Battle of Rawfolds Mill in April 1812—the Luddites’ struggle took on a more direct political color. Many railed against the monarchy and called for a republic. During one Luddite riot in Leeds, a standard bearer was seen to wave “a sort of red flag.” As E.P. Thompson put it in his classic The Making of the English Working Class, the weavers “trembled on the edge of ulterior revolutionary objectives.”

The Tory government under the decadent and careless regency of George IV, spooked by 20 years of revolutionary sentiment from France, had already crushed a reform movement set afoot by Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man. From November 1811, the state built a near-total system of repression. First came the constables and militias, then the infantry and cavalry, to enforce a dense thicket of special decrees and rulings: the complete criminalization of “combination” (forming a union), the punishment of swearing any kind of secret oath, the death penalty for belonging to a secret society. Worst of all: The pubs were forced to shut at 10 p.m. By the summer of 1812, the North of England was in a de facto state of occupation. Thirty-five thousand soldiers were deployed to keep order—more than the Duke of Wellington had under his command to fight Napoleon in Spain.

What the weavers grasped early, and what Merchant often emphasizes, is the inanimate nature of a machine. A machine cannot ruin someone’s livelihood or evict them from their home. It’s the hand behind it—the hand of the “innovator,” the entrepreneur, the capitalist—that forces the machine on the workers, undercuts wages, introduces the factory system, and pays the mercenary to guard the walls. “The explosion comes,” Merchant observes, “not when technology itself advances to any particular point, but when it’s used to disrupt the way we work and live.… The technologies that people are ridiculed for protesting tend to be the ones designed to profit at the protester’s expense.” This is part of the problem of referring to the “Industrial Revolution” as a synonym for “capitalism”: A locomotive could not sentence a Luddite to the gallows; a steamship did not write The Wealth of Nations. The Luddites understood that if a human hand was stealing their bread, only a human hand in turn could fight back with a hammer.

The movement was aided by an ambient, creeping anxiety about what the machines were doing to a world that was still largely rural and steeped in tradition. “The future,” Charlotte Brontë wrote in her late novel Shirley, about the Luddites, “sometimes seems to sob a low warning of the events it is bringing us.” Society was in transition, the essayist Thomas Carlyle believed, from a polity ordered by religion and duty to a regimented life under the foreman’s whip, destined to follow “a blind No-God, of necessity and Mechanism,” held in the clutches of “a hideous World Steam-engine.”

The same fear could be seen in William Blake’s apocalyptic yearning for a new Jerusalem and in Mary Shelley’s tale of a deluded scientist who cannot control his own creation. Lord Byron lent his poetry to the Luddites’ cause, drily observing that such a rapid shift could only be backed by extreme force:

Gibbets on Sherwood will heighten the scenery

Shewing how Commerce, how Liberty thrives.

The artist J.M.W. Turner saw it too, this passing, in his innumerable sketches of hillsides blighted by forges, and in The Fighting Temeraire, his famous study of a goliath warship stripped of its sails being hauled up the Thames by the paddlewheels of a dark squat steam tug; the new technology—ugly, metallic, grimy—is towing the old magnificence to its destruction. In this sense, the fate of England’s clothmakers, Luddite or otherwise, takes on a tragic hue. They were trapped. Behind them, not yet passed but no longer solid and reliable either, were the traditions and customs that had sustained them for centuries, their sense of independence, and their pride in crafting something tangible. Before them, coming quickly over the next hill, blotting out the horizon, was the capitalist with his machines building ever more momentum.

Merchant’s narrative of the Luddites’ struggle is sharp and speedy, arranged in short, tart chapters, and relying as much as possible on accounts that illuminate the secretive workings of Luddite cells. Occasionally, though, Merchant’s chatty pop-sci style becomes distracting. By adopting the legend of Ned Ludd as their public face, the machine-breakers “pioneered a meme-based approach to resistance,” Merchant claims. He describes the early machine bosses as “the first tech titans.” Merchant compares a nineteenth-century problem with a similar twenty-first-century one and glibly asks “Sound familiar?” Because some of the more moderate weavers campaigned for a machine tax to fund relief for the poor, he stretches to call them “some of the earliest policy futurists.”

This last example at least has the virtue of being funny, but it also makes a fetish of the wonk-like jargon of the same “innovators” and “disruptors” he’s trying to criticize. These are the tics and quips of a writer who doesn’t quite trust their reader and makes a plea for the relevance of their historical narrative by tricking it out with contemporary phrases. Most bizarre of all, Merchant keeps inserting Andrew Yang into his pages, calling him “the first modern mainstream presidential candidate to essentially forecast a second coming Luddism.” A few paragraphs later, Merchant compares Yang to the utopian socialist Robert Owen. Except that Yang is very far from a Luddite, or an Owenite, for that matter. He is, in fact, just another “policy futurist” whose basic “challenge” to the all-powerful tech bosses takes the form of a universal basic income, not a disciplined and covert campaign of machine-breaking.

This gets to the major fault in the modern sections of Blood in the Machine. Merchant hunts optimistically through the culture for evidence Luddism is on the comeback—and keeps being disappointed. He finds several podcasts (This Machine Kills, Tech Won’t Save Us), a couple of books (including Gavin Mueller’s Breaking Things at Work) but no trace whatsoever of a cloak-and-dagger, torchlight-and-hammer crusade to bust up servers and set fire to microchip plants. He cites the organizing efforts of New York’s taxi drivers against the encroachment of Uber, and Chris Smalls’s historic victory leading the Amazon union to recognition in Staten Island. If the timing of Blood in the Machine was a little different, Merchant no doubt would have included the Writers Guild of America’s victorious 146-day strike, which protested in part against the imposition of A.I. by studio bosses. Though workers have mounted these efforts in fields disrupted by new technologies—made all the more challenging by the fracturing, alienating nature of freelancing and piece-work—they are still union drives, which sit in a parallel tradition to the Luddites. Taxi drivers have not vandalized Priuses en masse; Amazon workers have not set about breaking packing robots; the WGA strikers did not trash their writer’s rooms.

By bounding the gap between 1812 and 2023, by glossing over some not inconsiderable events which happened in the meantime, Merchant misses a major development. In defeat, the Luddite movement did not spawn recurrent patches of machine-breaking: Its offspring was Chartism, the infant trade unions, the Revolutions of 1848. Just as the form and nature of capitalism have shifted, so too has the resistance against it.

In this sense the Luddites belong to their own moment, not ours; the moment when capitalism was only just forcing itself into the world, before its methods and laws became common sense, before the imperative of profit overtook all moral consideration. At the moment of its birth, it was most vulnerable, and the Luddites’ fury could be harnessed and focused by the bonds of tradition still intact. They were among the first to experience what it was like to be forced out of a meaningful, productive job and into a life of repetitive industrial labor, to see their old communities and customs riven apart, to experience the trials and vagaries of the wage system. We already live in that world; those social bonds have long since frayed; there is no golden age within living memory to draw inspiration from. But even as reality changes, shaped by the machines and their owners, there is still an essential truth in the Luddites’ outrage and determination, a truth that has survived 200 years of bitter experience. As Merchant puts it: “Some machines must be broken, so that they stop producing monsters.”