The protagonist of Max Porter’s Shy is Shy, a teenage boy given to wild bursts of rage. He has been excluded from the mainstream school system due to a long and sustained pattern of delinquency and now resides at the Last Chance school. Last Chance is an experimental teaching facility and therapy program for troubled boys, situated in a rickety and possibly haunted countryside mansion. Scraps of documentary narration suggest it takes a less disciplinarian approach to antisocial behavior than tends to be politically popular and that this may be one reason it is currently threatened with closure. Shy is not taking this development well at all.

Shy tells the story of a night in which Shy contemplates a plan for suicide and so reflects on the course of his life so far. Snatches of memory reveal a pattern of episodes of emotional turbulence which escalate, in a recognizably gendered fashion, into anger and destruction. We are told he was expelled from two schools, first cautioned by police aged 13, and first arrested aged 15. And that he has “sprayed, snorted, smoked, sworn, stolen, cut, punched, run, jumped, crashed an Escort, smashed up a shop, trashed a house, broken a nose, stabbed his stepdad’s finger.”

This may sound like a story about how trauma begets dysfunction (a very well-trodden terrain for novels at present, as Parul Sehgal argued in “The Case Against the Trauma Plot”), but Porter does something fresher and more interesting than drawing a line between, say, a chaotic home life and bad behavior. There is nothing particularly (or even quite) bad in Shy’s memories of his upbringing at all. What Porter portrays instead is a pattern of slights and rejections, mostly caused by Shy’s social awkwardness and confusion about how to relate to other people. There is the impatience of his stepdad and teachers; a childhood sleepover where the other boy begs to leave early because he finds Shy’s fidgeting tiresome; and various humiliations when he opens up to other teenage boys and they betray his trust.

There are some hints that his restlessness may be linked to a neurodevelopmental disorder, perhaps ADHD. But really what emerges over the course of the book is a picture of someone who is a little too soft for the world and deals with this by acting far too hard. In one telling scene, Shy remembers a night, when he was 6, when he half-woke to find “a red-dark featureless animal crawling slowly across the bedroom floor towards him.” As he fully gained consciousness he realized his stepdad was in the room with him. In a different kind of book, this would be the start of a memory about child sexual abuse. Here it is the moment when Shy learns definitively that Santa is not real: His stepdad was filling his stocking.

Shy’s backstory sits at odds with current trends in fiction and feels true to life in a way that the trauma plot often does not. It is of course true that one child will respond to a troubled and chaotic home life with delinquency and aggression, leading to addiction, say, in adulthood. But another will, with cold determination, channel the strain of this into an immaculate academic performance or extraordinary sporting success as a means of self-sufficiency and escape; perhaps they will develop a tendency toward emotional distance but no issues that will land them in prison. Likewise one child of a doting mother like Shy’s will be well-adjusted and easygoing. Another will be violent and impulsive like Shy, for reasons that are not as straightforward as we would perhaps like them to be.

It is an uncomfortable truth that some people are well adapted to the world as it is (or at least appear to be) and some, whatever advantages they have been born into, simply are not. The discomfort in this truth lies, I think, in the reality of how we tend to apportion sympathy as a society. Which of the above children would we treat sympathetically (that is, with support and understanding)? I would say none, except the well-adjusted product of a loving home. At present our culture says the people most deserving of sympathy are those who are best at, and most comfortable with, advertising their vulnerability and sensitivity in a palatable way: An emotional outburst is good, but it must be tears instead of anger.

Is this fair? Of course not. The world (as the second child in the above paragraph understands well and has grimly made peace with) is not. But the novel can be a space to probe accepted attitudes like these. Porter sets himself the challenge of rendering the least palatable of these children sympathetic: the kind of boy who has a lot going for him, a lot of privilege, and can’t seem to do anything but make a mess of it.

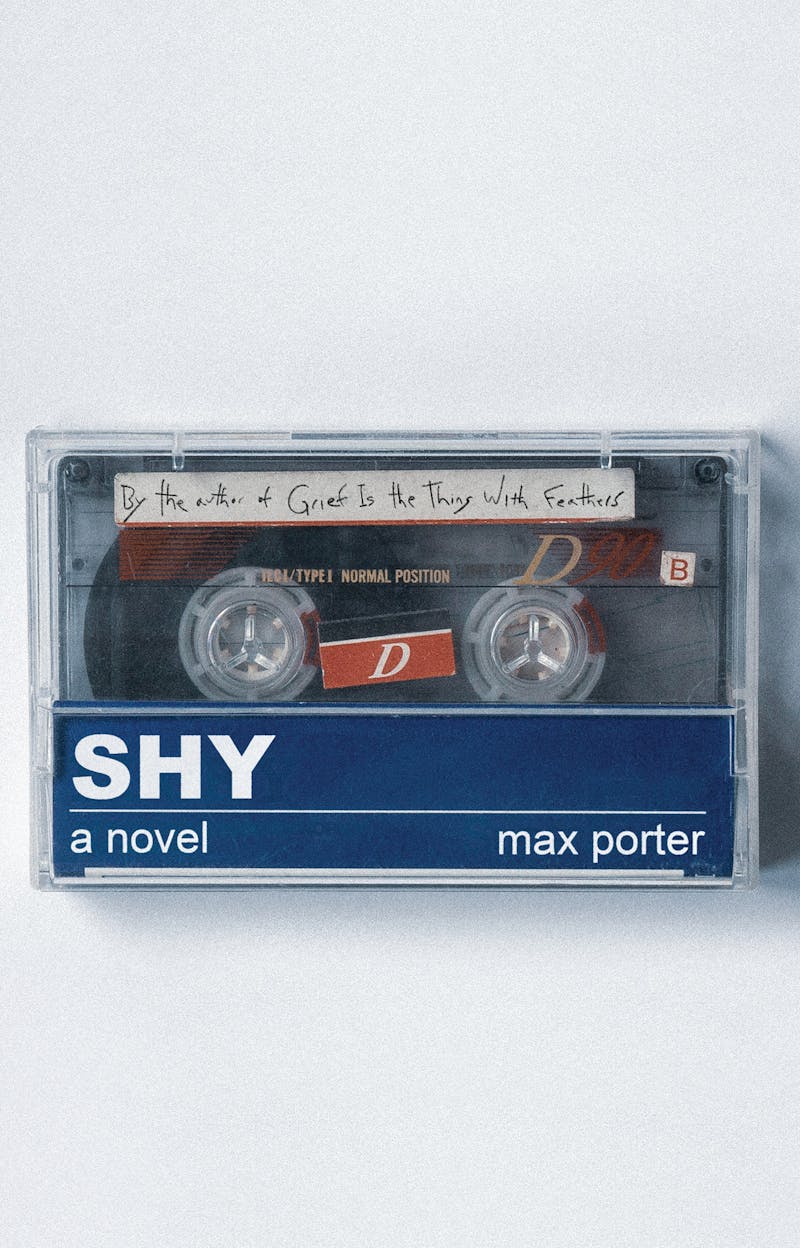

Porter succeeds at this, in part because the distinctive fragmentary stream of consciousness style he has developed, first in Grief Is the Thing With Feathers, then in Lanny and The Death of Francis Bacon, fosters a close proximity between the reader and his characters and their emotional landscape. His technique of layering snatches of thought, memory, and feeling deftly, in a manner that feels instinctive, makes Shy’s perspective seem not only understandable but inevitable to the reader. But this success is also partly due to the immersive, compulsively readable quality of Porter’s writing: A novel that asks you to spend time with a difficult character is most successful, I would argue, when it is enjoyable and entertaining to read.

There are unexpected flashes of humor throughout the book, which Porter generates from the disconnect between Shy and basically everyone else, even his closest friends. In one passage Shy is thinking about the “mathematical perfection” of drum and bass, of samples “sounding like divine intervention” and so on. But when he talks to his friends about music, he just says, “Nice. Yeah. Fucking love this tune.” Stunted communication is used to comic effect elsewhere too, like when Shy’s mum refers to him as “staying indoors all day, sitting around listening to his drums and bass,” in the kind of tiny language slip that underlines a lack of shared context.

Elsewhere there is an affecting softness to Shy’s worshipful relationship with an older cousin, Shaun, whose “hee-haw smoker’s laugh Shy’s been trying on for size.” Porter captures the guardedness of male intimacy, often facilitated by substances: Shaun and Shy’s bonding consists of doing cocaine off a car dashboard in a car park on Saturday afternoons as they listen to mixtapes. And the disappointing elements of this relationship are handled poignantly without slipping into mawkishness: “His cousin Shaun hasn’t picked up when he’s called him recently. It’s been ages. Maybe he’s got a new number or he’s not living in the same place.”

The question of sympathy is not the only focus of Shy. A story about an alienated, angry teenage boy is, of course, also a story about masculinity and male socialization. And Shy addresses elements of this process that tend to be ignored. There is an old, questionable, adage that boys tend to “fight it out” while girls deal with interpersonal problems via bitching and gossip. Accordingly, some of the most interesting passages of the book are those that detail the cattiness and gossipy nature of the boys at Last Chance, and the emotional devastation this wreaks on Shy. One night, for instance, Shy sits up talking with a boy named Cal and confides in him about a sexual encounter during which he “came before he was properly in.” Cal commiserates with him, but the next day marches into the dining room and announces the story to all the other boys, earning Shy the nickname “one pump Shy.”

But there is a more interesting perspective still on gender, lurking at the edges of this book. Like all of the women in Shy, Shy’s mother is caring, thoughtful, and supportive. She has also struggled with depression. In a family therapy session, Shy’s mother tries to describe Shy’s anger as she understands it: “Shy’s inside, but the skin is also him, so angry, so true. I’m almost envious.” Shy has a certain freedom—to express his fury, to break things, to not care—that is generally not afforded to women or teenage girls.

Porter revisits this idea again at the end of the book, when Shy has a hallucinatory vision of the ghost of a troubled teenage girl haunting the Last Chance house. He sees her planning a suicide of her own, more strategically and meticulously than he has. He feels “sloppy in comparison”; he has “no real plan, whereas she has a sudden, clear ambition for a neat and hurtful leaving.” In a rush he experiences the force of her emotional landscape, a world he hadn’t previously given much thought to: “Angrier than Shy, it shocks him to feel it, a lesson and a taste.”

The girl’s anger is more unexpected, and truer to life, than the often narrow emotional ranges displayed in trauma plot fiction. In a fictional landscape in which destructive (or indeed any) behavior always maps to a succinct backstory, the weight of personality is dampened; characters can end up feeling like flat stock types, their particular course through life predetermined by their response to certain obstacles only. The only distinction may be in socialized identity behavior: A woman does X because Y happened to her, whereas a man does Z. A teenage girl is sad; a teenage boy is angry. Real people, as Shy realized, are less predictable.