More than a decade ago, on the first day of a college seminar titled “The American South,” Glenda Gilmore—one of the deans of Southern history—challenged my classmates and me to define the borders of the South. It was a surprisingly difficult task. Everyone agreed on, say, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina, but what about Oklahoma—was it Western or Southern? What about Kentucky, home state of Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln? Perhaps Missouri, the setting of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn? Undoubtedly northern Florida, but whither Miami? Why not New Mexico, which after all is south of Virginia? Does Delaware count? The exercise ended without any certainty, which surely was the point.

To the eminent (and eminently racist) Southern historian U.B. Phillips, the South was defined by its weather. Elsewhere, he labeled white supremacy the region’s “central theme.” To others, the South is simply the former Confederacy. To many, there’s an unspoken but firm association between Southernness and backwardness, or religion, or poverty. These assumptions position the South as a region apart, an “other” place, an American heart of darkness, a foil for the more enlightened North or the more entrepreneurial West.

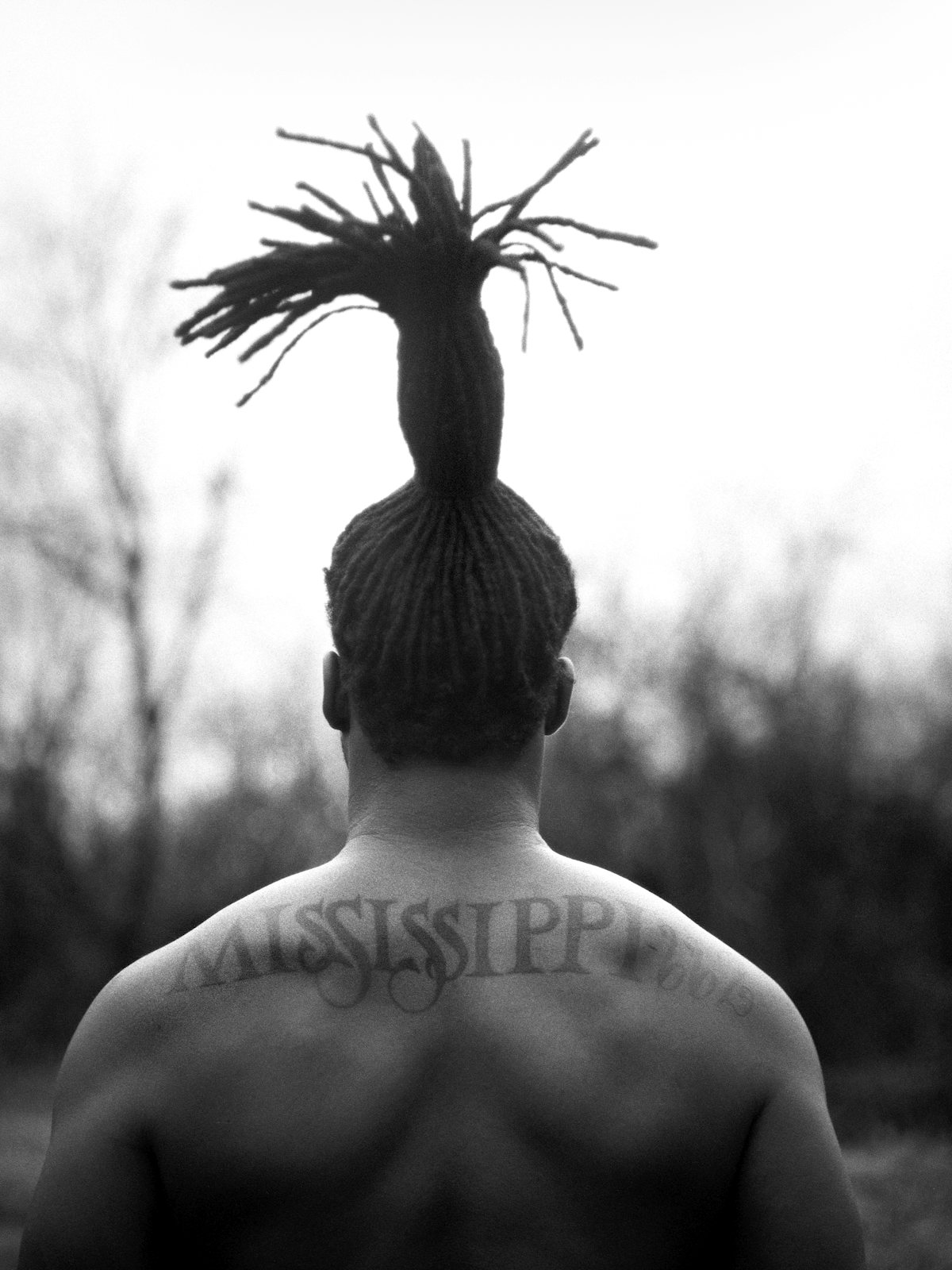

It’s ironic, then, that the South has also become a stand-in for American authenticity. “The most violent and inequitable region of the country produced a disproportionate amount of the modernist literature, adventurous self-taught art, and genres of music and popular styles of religion, which entered into and then transformed the artistic sensibilities and cultural soundtracks of the twentieth century,” writes Paul Harvey in a penetrating essay in A New History of the American South. Consider the iconic American musical forms, the blues, jazz, country, gospel, soul—all have Southern origins. What would American religion look like without Southern Baptists, Pentecostals, the broader evangelical movement? Is modern American literature even imaginable without William Faulkner, Zora Neale Hurston, Carson McCullers, Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty, or Thomas Wolfe?

Edited by the acclaimed University of North Carolina historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage, the 15 essays in A New History recount the origins, histories, and influences of the South. The specter of “Southern distinctiveness”—the idea that the region is uniquely, characteristically violent or dysfunctional—hangs over the collection, but it “is not an organizing conceit in this volume,” Brundage writes. Instead, he and his contributors have attempted something rarer: an entirely new narrative of the American South. Again and again, its essays emphasize that the South has not been static, “steeped in timeless traditions,” but rather has been “punctuated again and again by wrenching transformations.”

A dynamic South. The idea is counterintuitive precisely because of the prevalence of magnolia-shrouded imagery, because of accounts that position the South as the consistent spoiler, emphasis on the consistent. But the South that emerges from A New History is fresh and exciting in its unfamiliarity. It is a region of unstable boundaries, demographics, and politics, a site of shifting powers and protean culture. The South hasn’t always been a place of cruelly concentrated wealth, of rigid racial boundaries, of grinning, sweating, sloganeering, archconservative politicians. It has also been a launchpad of change, of radicalism, of resistance—and its future is yet unwritten.

In the beginning, there were monsters. To stroll through the Ice Age South would be to encounter many familiar plants—from maples and hickories to, yes, magnolia and dogwood—but also giant land tortoises, giant moose, giant beavers, dire wolves, American lions, and (in Florida) giant armadillos. The coastlines were well over 100 miles beyond where they are today, and only with the warming of the globe did the glaciers retreat, the rivers stabilize, and the Southern forests assume a now-familiar ecology. Most of the great American megafauna died off.

Humans occupied what is now the South for many thousands of years—most Southern Native American origin stories involve west-to-east migrations, a narrative supported by the archaeological record—but the end of the Ice Age about 11,000 years ago spurred the development of larger communities, the centralization of political power, increased trade, increased warfare, and eventually the domestication of plants and a transition to agricultural societies. Thus did climatic change set in motion the first of the South’s series of metamorphoses.

In A New History’s first essay, the historical anthropologist Robbie Ethridge covers these millennia of transformations swiftly yet with aplomb and respect. Eventually, the colonizers arrived. First came the Spanish, who encountered a dense web of chiefdoms and a century of resistance. Even as other imperial powers—the English, the French—set up small outposts, Native Americans continued to constitute the majority of the region’s population until well into the eighteenth century.

Over time, the English—with Native allies and Native slaves and then, increasingly, African slaves—became more powerful, spreading from Virginia to Maryland to Carolina (not yet bifurcated), but social relations remained malleable. Some seventeenth-century Africans lived freely in the South; some even owned slaves themselves; and others worked for a time as indentured servants, a status they shared with legions of poor and striving whites. In the mid–seventeenth century, fearful that the growing class of temporary and former servants might displace them, white property owners passed laws that phased out indentures for white people and established a system of chattel slavery (permanent and heritable) for Black people. This effectively divided the working class along racial lines, exactly as the tobacco planters and colonial overlords intended. Indeed, many historians have shown how this transformation created the modern idea of race itself. The English colonies transformed, Jon F. Sensbach writes in his essay, “from a society with slaves to a slave society.”

Slavery grew to such an extent that some areas (famously South Carolina) became majority Black in the eighteenth century, and plantations began farming rice, drawing on captured Africans’ knowledge of the crop. Slave revolts became common features of life in the South, and many Black people escaped and found refuge in the declining Spanish colony of Florida or within Native communities.

“It may be no exaggeration to say that in the southern colonies, enslaved Africans made the first bids for independence, helping to trigger the Revolution,” writes Michael A. McDonnell in his essay. Escape attempts and rumors of impending armed revolt greatly heightened tensions within the Southern colonies, with many colonists believing that “the British would liberate slaves.” When revolution eventually broke out in the mid-1770s, many in the South were either loyal to the British or too focused on the “threat of insurrection by enslaved Africans” to join the war effort. The Continental Congress made George Washington of Virginia the head of its army in an attempt to gin up Southern support for the war, but thousands of “loyalists” across the region nonetheless waged guerrilla warfare against the revolutionaries. In the end, the British were simply too disorganized to exploit their advantages (including the legions of Black people fleeing to their lines), but victory in the war for colonial independence was “a close-run thing,” McDonnell concludes.

The Revolutionary War had been monstrously costly, a destructive cataclysm, and an economic downturn and widespread anger followed in its wake. This spurred a rise in Southern “localism”—a desire for greater control over local affairs—yet “the South” was not yet perceived as (nor did its residents perceive themselves as belonging to) a distinctive region. It was, among other factors, fights over slavery that hardened the categories of “the North” and “the South.” The Southern states were home to an agricultural political economy deeply dependent on slavery, and even as abolition took hold in Haiti, Spanish-controlled Latin America, and (parts of) the British Empire, powerful Southerners united in support of the system that enabled the mass cultivation of rice, tobacco, and cotton. Dissenters (of many races) fled north or west; ideas of whiteness solidified in the aftermath of Indian expulsion and the expansion of suffrage to poorer white men; slave-state politicians began to identify as “Southerners”; and, as Martha S. Jones writes in her essay, Northern abolitionists began speaking of slavery as “a distinctly southern problem.”

Of course, the South remained a site of “porous” boundaries, as Kate Masur emphasizes in her chapter. It was home to a diverse array of immigrants, defiant Native communities, and vibrant (and surprisingly mobile) slave subcultures. Rail and steam transport, as well as the global commodities trade, connected the South to the world at large, and the region’s southern border shifted as settlers in Texas warred with Mexico over land. The diversity of crops, climates, and types of social organization meant that each area had its own distinctive political orientation, a fact that frustrated those, like Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who pushed for a collective Southern separatism.

Eventually, those in power—“planter-politicians,” to borrow a term from Gregory P. Downs’s essay—grew so fearful of abolition that they launched a war. “By drawing a sharp political line around the Confederate states,” Downs continues, “the war made real what had only been metaphorical.” From a distance of a century and a half, it’s easy to forget that the South could have won the war. “There was in fact nothing foreordained about the survival of the American nation,” Masur writes, noting the proliferation of new nations and revolutionary movements throughout the nineteenth century. Only through a combination of enhanced industrial capacity, the neutrality of European powers, and Black rebellion so widespread that W.E.B. Du Bois would label it a “General Strike” did the North clinch victory and keep the South as merely the southerly region of a larger nation.

“But the Confederate dream did not die quite yet,” Downs notes with foreboding. “The nationalism created during the war would outlive the nation that failed.”

In the years following the Civil War, a new South seemed possible. Thousands of Black men won elections to state legislatures, Congress, and local offices such as magistrate, deputy sheriff, and coroner. Public education expanded rapidly, reaching many poorer whites and Black people for the first time, and a spate of colleges and technical schools opened for former slaves. In some places, poor farmers (white and Black) secured autonomy and even land itself. Reconstruction, as this period is known, could have been a second—and far more revolutionary—American Revolution.

Instead, white people across the South struck back with a vengeance. “Many could accept the death of the Confederacy,” Downs writes, “but not of their local power.” Vigilante groups—of which the most famous is the Ku Klux Klan—arose, and in several states former Confederates effectively staged violent coups to retake power from legitimate Reconstruction governments. By the 1880s, nearly half of former slave-owning planter families had lost their lands, and a postwar financial downturn and a slide in cotton prices had helped turn the South into “a symbol of economic and social backwardness.” But the remaining former slaveholders had united with ascendant manufacturing and financial elites to retake power.

They became a new kind of aristocracy—the “Bourbons,” in the parlance of the time—and consolidated their wealth and control by reviving many features of the slave system in all but name. The Bourbons withdrew access to the polls by systematically disenfranchising Black voters; they yoked poor families (Black and white) to large plantations by paying them only in store credit or a “share” of the crops that they farmed; they reestablished large-scale involuntary labor by “leasing” convicts (many hastily convicted of vaguely defined crimes such as vagrancy). By 1880, the region was producing 60 percent more cotton than it had in the 1850s.

The rich held “three aces,” in the words of Scott Reynolds Nelson: “access to credit, title to land, and growing political power.” They also arrogated to themselves the power of the executioner, and tactics such as lynching and race riots (i.e., mass murder campaigns) suppressed resistance to newly enacted laws that instantiated segregation in schools, businesses, residences, and trains and streetcars. Black people continued to carve out pockets of prosperity even in a segregated society, establishing their own schools, businesses, and a handful of utopian, separatist towns. Yet separate was never equal, and—as Blair L.M. Kelley emphasizes in her essay—things were even less equal and more violent in rural places across the South.

In the early twentieth century, poverty, illiteracy, and all manner of illnesses plagued the rural South. Reformers of all races—motivated by embarrassment, compassion, greed, or some flavor of Christianity—sought to sand off the region’s roughest edges. Some decried planter venality only to scapegoat Jews and Roman Catholics; some pushed prison reform and women’s rights only to promote virulent racism; some Black reformers revealed disturbingly conservative tendencies even as they fought against the indignities of Jim Crow. “Southern white reformers managed to ameliorate the most extreme disparities in the region,” concludes Natalie J. Ring, “but only to the degree that their efforts delayed an eventual reckoning over the extent and nature of inequality in the South.” Eventually, the flood of federal cash that came available during the New Deal improved everyday life considerably across the South, even as its transformative potential, too, was blunted at the insistence of a rising class of Southern “demagogue” politicians (such as James K. “White Chief” Vardaman and Jeff “Wild Ass of the Ozarks” Davis).

Marginalized Southerners of all stripes had never stopped fighting against oppression, but only in the mid–twentieth century did a broad-based civil rights movement become possible. Soldiers returned home and started organizing; students sat in at segregated lunch counters; preachers preached; writers wrote; many Black people voted with their feet and left the South in the Great Migration; many other Black people stayed, and some started hoarding guns, forming armed resistance groups such as the Deacons for Defense, preparing to meet violence with violence. Kari Frederickson’s essay on the South and the state in the twentieth century covers these developments fluently but, by necessity, very quickly.

Kenneth R. Janken, in the collection’s final contribution, looks more squarely at the postwar freedom struggle, noting its myriad successes, but also how its most radical dreams—of economic rights, wealth redistribution, an end to U.S. wars of aggression—were extinguished as moderates and liberals repeatedly branded agitators as communists or degenerates and expelled them from public life. This pattern continued for decades, perhaps peaking (though by no means ending) in the 1986 congressional race in Georgia, when John Lewis (who had abandoned his firebrand origins and embraced “‘practical,’ moderate change,” in Janken’s words) smeared his left-wing opponent, Julian Bond, by accusing him of using cocaine and taunting him to take a drug test.

The solidly Democratic South started turning Republican as the Democrats became more associated with civil rights, as charismatic conservative politicians—Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, Donald Trump—effectively consolidated support. Protestant evangelicalism, meanwhile, spread rapidly across the land, its tribunes preaching adherence to patriarchal gender norms, promoting the pursuit of prosperity, and increasingly urging their flocks to vote Republican. The region’s farm population plummeted as Southern states urbanized and suburbanized and as the remaining farmers became more dependent on transient labor. Certain segments of the South (Houston, Austin, Atlanta, perhaps even Raleigh/Durham) became part of the much-ballyhooed “Sun Belt,” while other parts (central Florida, northern Alabama, northeastern Virginia, Dallas-Fort Worth) rose with the “Gun Belt,” as military contractors—and the military itself—exploited the region’s cheap land, low wages, and nonunionized workforce.

Looking back, the legacy of the battles for civil rights “appeared paradoxical,” notes Paul Harvey. While de jure segregation had ended, practically speaking, white and Black people in the South—especially in rural areas—“remained quite separate, and the extent of Black poverty rivaled that of the worst areas of the country.” And though the South was “born global,” adds Peter A. Coclanis, recent waves of migrants from Asia and Latin America have altered its demographics, provided an influx of economic dynamism even as industrial jobs have disappeared, and—in a broader sense—challenged the many caricatures of the South that A New History excels at puncturing.

A New History is a blockbuster collection that exceeds 600 pages, but it is not an encyclopedia, so it’s natural that some holes remain. The essays of A New History have little to say about queer Southerners, the place and role of prisons in the South, the border, Tejanos, Miami and the “Nuevo South,” and Walmart. Essays certainly address Southern radicalism, but the name Huey Long never appears, and the significance of Southern socialists and union organizers is, at times, undercounted. The South is the birthplace of the modern environmental justice movement, but this goes unmentioned.

No one volume can be truly definitive. What is so exciting about A New History is its refusal to accept the “definitive” shibboleths of the past, its insistence on integrating new findings and new voices into the story of a region almost invariably slapped with the labels of “timeless” or “unchanging.”

Some of the most captivating essays in the book stray from conventional chronologies and instead zoom in on specific people and places, telling their stories as stories of the South. In “The Bourbon South,” for instance, Scott Reynolds Nelson explores the postbellum South through the eyes of two observers, both named Henry Grady. The first was a prominent newspaper editor and political leader who “hoped to cobble together a common region and assemble a new elite to rule it.” The second was an obscure laborer who literally helped link the South together by working on interstate railways, and who left behind a collection of letters, scrawled almost illegibly in purple crayon, which cast doubt on the “New South” that his wealthier doppelgänger was building. He found Louisiana to be bewildering, and the Mississippi Valley ugly and inhospitable; both were described as another “country.” His letters reveal how, even three decades after the Civil War, “there was no common South.”

In an otherwise glowing review of A New History, Kirkus remarked that the collection “briefly stumbles” when contributors focus “on select individuals rather than the South as a whole.” I disagree. It is impossible to cover “the South as a whole”—not only because of the multitudes contained within any place, but also because the region is itself a construct, a convenient fiction.