The Supreme Court narrowed a key exception in copyright law for unauthorized uses of artistic work on Thursday, ruling that Andy Warhol’s foundation had inappropriately licensed a painting of the musician Prince that was itself derived from a photographer’s earlier work. The decision will make it easier for artists whose work is later used or borrowed by others without permission to take legal action for infringement.

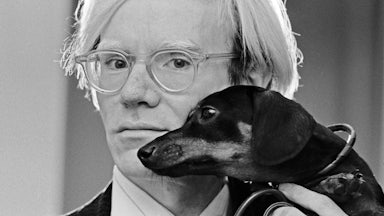

On one side of the dispute was Warhol, who became one of the twentieth century’s most recognizable artists through his commentaries on celebrity and consumerism. (Warhol died in 1987, and his copyrights passed to the foundation.) On the other side was Lynn Goldsmith, an acclaimed photographer of musicians whose 1981 portrait of Prince formed the basis of one of Warhol’s signature painting series.

The court ultimately sided with Goldsmith and found that the foundation’s decision to license a painting for a magazine cover in 2016 did not qualify as “fair use” under federal copyright law. “Goldsmith’s original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote for a 7–2 majority in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith. “Such protection includes the right to prepare derivative works that transform the original.”

Though their specific clash was at the center of the case, the ramifications could extend far beyond Goldsmith and Warhol. The Supreme Court’s new understanding of fair use and how it applies to “transformative” works could have major consequences for copyright disputes for musicians, photographers, and writers across the country. It could also have an immediate impact on the fledgling artificial intelligence industry and how it trains algorithms to create “new” works.

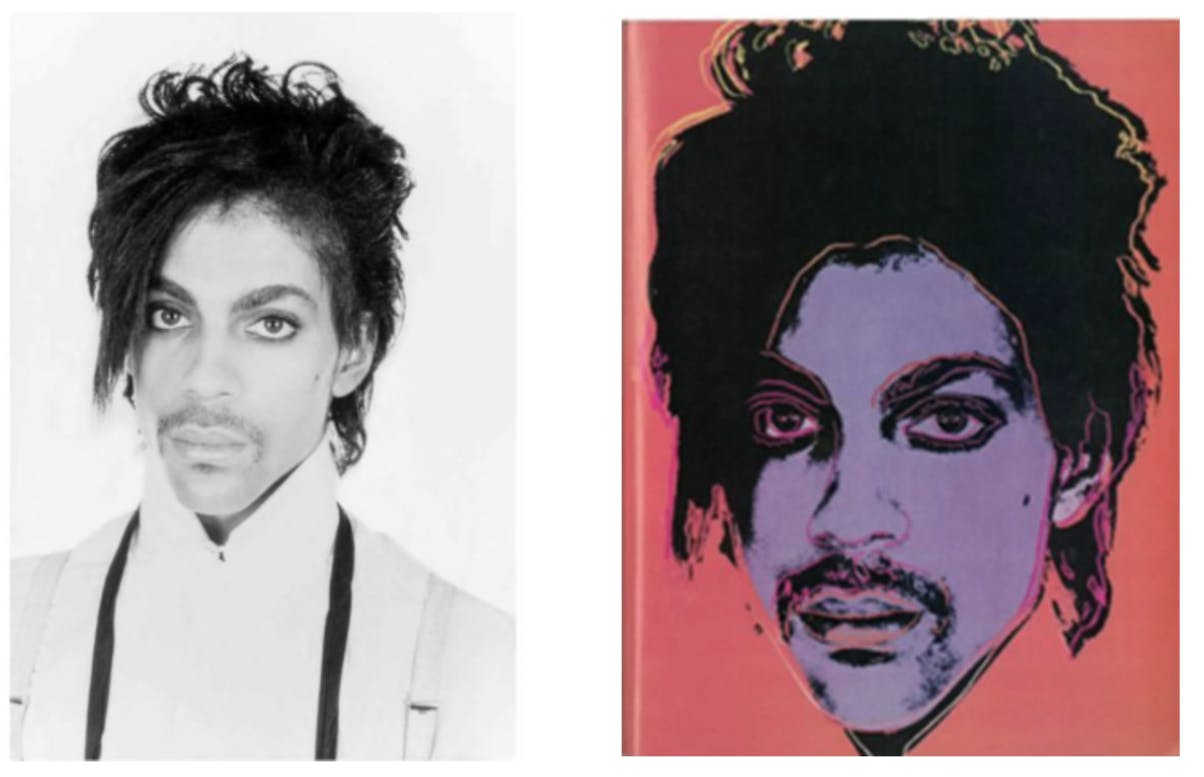

The underlying dispute began in 1984 when the publishing company Condé Nast licensed one of Goldsmith’s portraits of Prince for $400 for a one-time use as an artist reference in an upcoming issue of Vanity Fair magazine. Vanity Fair’s editors then gave the portrait to Warhol, who used his famous silk-screening technique to substantially alter the image for the magazine to use in the upcoming issue. (You can see the two versions above.) Goldsmith did not know of Warhol’s involvement at the time.

After that assignment, Warhol then used Goldsmith’s original portrait to make 15 other silk-screen variations of Prince’s image, each of which resembles Warhol’s usual style of celebrity portraiture. Those images, collectively known as the Prince Series, became prominent works of art in their own right. Copyright for them passed to the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Goldsmith was unaware of the Prince Series’ existence until the musician’s unexpected death in 2016, when Condé Nast licensed one of the Warhol images—an orange-tinged version titled Orange Prince—from the foundation for a magazine cover commemorating Prince’s life and career. The foundation received $10,000 for its use.

Goldsmith threatened legal action against the foundation shortly thereafter. The foundation responded by preemptively suing her so that a judge could declare that the work hadn’t infringed on her copyright or that it amounted to fair use. Goldsmith then countersued the foundation to argue that the licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast had, in fact, infringed upon Goldsmith’s copyright. A federal district court judge sided with the foundation, concluding that Orange Prince was sufficiently “transformative” under copyright law to be an entirely new work of art. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals reversed that decision, leading the foundation to ask the Supreme Court to intervene.

At issue is whether the Warhol painting counts as “fair use.” That doctrine allows for copyrighted works to be used in certain contexts—education, critique, news reporting, and so on—without counting as infringement. Under federal copyright law, courts look at four factors to determine whether an unauthorized use counts as fair use: the “purpose and character” of the use, the “nature of the copyrighted work,” the amount or proportion of a copyrighted work that was used, and the potential market effects on the use.

Much of the case focused on the first factor. The foundation argued that Orange Prince was the result of Warhol’s “transformative” use of Goldsmith’s original portrait and thus counted as an entirely new artwork. Fair use accordingly did not apply, in its view. Goldsmith countered that Orange Prince retained her portrait’s most essential features despite Warhol’s characteristic alterations to the image’s coloring and composition, including the removal of Prince’s neck and torso.

Sotomayor, writing for the court, sided with Goldsmith. She noted that first factor’s uses are typically (but not always) noncommercial in nature. In this case, however, Warhol’s painting was being licensed for profit for a magazine cover, something that Goldsmith could do and has done with her own photography. “Taken together, these two elements—that Goldsmith’s photograph and AWF’s 2016 licensing of Orange Prince share substantially the same purpose, and that AWF’s use of Goldsmith’s photo was of a commercial nature—counsel against fair use, absent some other justification for copying,” she wrote. “That is, although a use’s transformativeness may outweigh its commercial character, here, both elements point in the same direction.”

The court also rejected the foundation’s claim that Warhol’s painting was sufficiently “transformative” to qualify for fair use in general. Indeed, Warhol became famous in no small part because of his ability to reproduce existing images in new contexts. But Sotomayor rejected that interpretation as well, contrasting Orange Prince with Warhol’s famous Campbell’s Soup series. While the Campbell’s Soup design is used by the company to sell soup, she noted, Warhol’s adaptation of it was “an artistic commentary on consumerism, a purpose that is orthogonal to advertising soup.” The same couldn’t be said for Orange Prince without destroying an artist’s ability to profit from secondary works, Sotomayor noted.

“Many derivative works, including musical arrangements, film and stage adaptations, sequels, spinoffs, and others that ‘recast, transfor[m] or adap[t]’ the original add new expression, meaning or message, or provide new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understandings,” she wrote, quoting from a federal copyright statute. “That is an intractable problem for AWF’s interpretation of transformative use. The first fair use factor would not weigh in favor of a commercial remix of Prince’s ‘Purple Rain’ just because the remix added new expression or had a different aesthetic.”

Justice Elena Kagan, joined only by Chief Justice John Roberts, sharply dissented from Sotomayor’s conclusions. She argued that her colleague had fundamentally misread copyright law and, perhaps just as importantly, also fundamentally misunderstood how art works. Kagan’s dissent doubles as a brief recap of how writers, musicians, and visual artists borrow from one another and reinterpret each other’s work down through the ages. She bounced from Diego Velásquez and Francis Bacon to William Shakespeare and Arthur Brooke to Roy Orbison and 2 Live Crew to illustrate, in her view, how the majority’s conclusions could imperil artistic creativity.

“The majority thus treats creativity as a trifling part of the fair-use inquiry, in disregard of settled copyright principles and what they reflect about the artistic process,” Kagan wrote. “On the majority’s view, an artist had best not attempt to market even a transformative follow-on work—one that adds significant new expression, meaning, or message. That added value (unless it comes from critiquing the original) will no longer receive credit under factor 1. And so it can never hope to outweigh factor 4’s assessment of the copyright holder’s interests.”

Toward the end, in blunter and less legalistic terms, Kagan argued that the majority opinion would be damaging to all sorts of creative endeavors by making it harder for derivative works to be profitable. “It will stifle creativity of every sort,” she concluded. “It will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.”

In this dispute, Sotomayor and Kagan traded some unusually pointed remarks at one another. Justices typically end their introductory sections with the phrase “I respectfully dissent” or, in direr circumstances, just “I dissent.” Kagan kept the “respectfully” but added a lengthy footnote where she noted that Sotomayor’s opinion was “trained on this dissent in a way majority opinions seldom are,” referring to Sotomayor’s frequent points of rebuttal on behalf of the court. “Maybe that makes the majority opinion self-refuting?” Kagan asked. “After all, a dissent with ‘no theory’ and ‘no reason’ is not one usually thought to merit pages of commentary and fistfuls of comeback footnotes.”

Sotomayor, for her part, described Kagan’s dissent at various point as “stumped” on a particular legal question, suggested that the dissent “either does not follow, or chooses to ignore, this analysis” on another point, and accused the dissent of “a series of misstatements and exaggerations” along the way. I won’t offer a blow-by-blow recap of the disagreements, but it is worth highlighting their existence, if only because they underscore the depth of the disagreement between the two justices and, perhaps, because they reflect the stakes of the case for a wide range of creative professions.

While Kagan was focused on the potential plight of future artists making derivative or transformative works, for example, Sotomayor focused on the effects for Lynn Goldsmith, whose own original creative work was at issue here. “These claims will not age well,” Sotomayor wrote, referring directly to Kagan’s “stifle creativity” passage. “It will not impoverish our world to require AWF to pay Goldsmith a fraction of the proceeds from its reuse of her copyrighted work. Recall, payments like these are incentives for artists to create original works in the first place. Nor will the Court’s decision, which is consistent with longstanding principles of fair use, snuff out the light of Western civilization, returning us to the Dark Ages of a world without Titian, Shakespeare, or Richard Rodgers.”

The ruling was closely watched in the art and creative communities for those very reasons. The American Society of Media Photographers, of which Goldsmith is a member, celebrated the outcome as a vindication of her own legal and professional interests. “Lynn Goldsmith is not looking to reap unwarranted benefits; rather she is looking to enforce her rights to have her work, passion, and experience not be used without proper compensation,” Thomas Maddrey, the organization’s chief legal officer, wrote on Thursday.

Some music-industry organizations also celebrated the move. Prominent musicians have been at the center of a number of major copyright disputes in recent years. Ed Sheeran prevailed against a lawsuit earlier this month that claimed one of his Grammy-winning songs had copied material from Marvin Gaye’s “Let’s Get It On.” Such disputes are increasingly common in some genres in music because of the limited number of chord combinations that are available.

The National Music Publishers’ Association welcomed the ruling as a potential tool against another perceived threat on the horizon: A.I. programs that can generate new music based on existing works. “This is an important win that prevents an expansion of the fair use defense based on claims of transformative use,” David Israelite, the organization’s president, told Billboard magazine on Thursday. “It allows songwriters and music publishers to better protect their works from unauthorized uses, something which will continue to be challenged in unprecedented ways in the artificial intelligence era.”

Those programs, which process massive data sets of existing sources to “learn” how to create new visual, textual, or audio material, raised concerns about copyright and intellectual property long before Thursday’s ruling. In March, the U.S. Copyright Office rescinded most of an independent comic book’s copyright after learning that its creator had used A.I. programs to generate the artwork for it. Lawsuits have also been filed against some A.I. companies by artists who allege that their work was used to “train” the programs that “create” new artwork.

The Supreme Court hasn’t yet taken up a case on A.I. programs, and none appear to be imminent. But there are already some signs that the justices are pondering the legal questions that it raises. During oral arguments in March in a case on Section 230, the general liability shield for internet companies, Justice Neil Gorsuch suggested that it might not apply to A.I. generation. After Thursday’s ruling, its 15 minutes of fame before the Supreme Court could come sooner rather than later. My apologies to Andy Warhol for the reference, but given the circumstances, I think he’d understand.