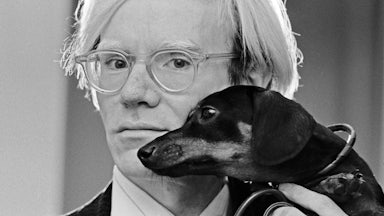

When I wrote about the Supreme Court’s decision to take up Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith last March, I wrote almost in jest that the justices would have to answer an age-old question: “What is art?” On Wednesday, the justices wrestled with just that issue—and how the law should treat “derivative” or “transformative” works of it. It’s unclear how the court will come down in this case, but a victory for either side could have broader implications for the boundaries of fair use and copyright across American culture.

The case centers on a series of portraits of the artist Prince, who died in 2016. Lynn Goldsmith, a musician and photographer who specializes in portraits of prominent singers and songwriters, captured the image in question during a session with Prince in 1981. Three years later, her photo agency licensed the image to Vanity Fair for use as a reference for an illustration for a story about Prince. The magazine then gave the photo to Warhol, who used his famous silk-screening technique to create a stylized version of Goldsmith’s portrait.

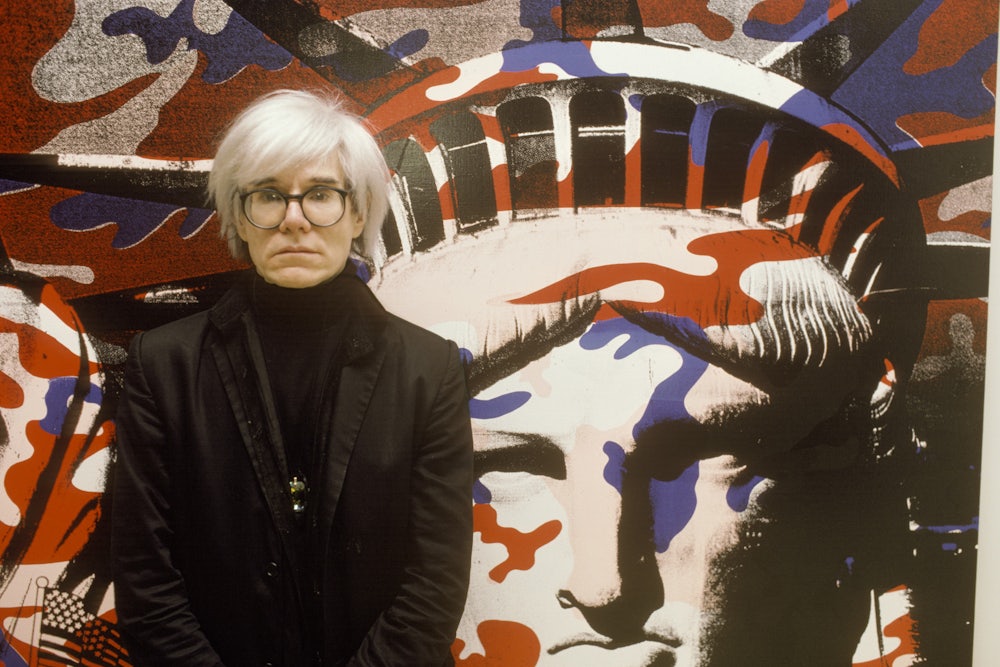

Warhol then used the image to create more than a dozen other new works of the pop musician. The Prince Series, as it was later called, became famous within the modern art community but remained unknown to Goldsmith herself until 2016. That year, Vanity Fair published a commemorative issue on Prince’s sudden death, which used one of Warhol’s versions for its cover. Goldsmith caught wind of it, contacted the Warhol Foundation—which handles his licensing rights—and suggested she might take legal action for violating her copyright to the original portrait. (Warhol himself died in 1987.) The foundation responded by suing Goldsmith first to obtain a declaratory judgment in their favor in court.

According to the foundation, Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s portrait counted as “fair use” under federal copyright law. That doctrine generally allows the unauthorized use of copyrighted works in some circumstances. Copyright laws require courts to weigh four factors when they decide whether the fair use doctrine applies: the “purpose and character” of the use, the nature of the original work, how much of the work was used, and the use’s effect on future marketability of the original work.

The foundation has argued that Warhol’s alterations of the original image were “transformative” enough to qualify for fair use protections, meaning that he had substantially changed the original portrait enough for it to count as a new, separate work. Goldsmith countered that while Warhol had indeed made plenty of changes by applying his signature alterations to the work, it was still derivative of her original portrait and that its ultimate effect relied upon the specific artistic and technical choices she had made during its composition.

A federal district court initially sided with the foundation on the transformative nature of the work, but a three-judge panel in the Second Circuit Court of Appeals overruled that decision and found in Goldsmith’s favor. “While the cumulative effect of [Warhol’s] alterations may change the Goldsmith photograph in ways that give a different impression of its subject, the Goldsmith photograph remains the recognizable foundation upon which the Prince Series is built,” Judge Gerald Lynch wrote for the panel.

During oral arguments on Wednesday, the foundation urged the court to consider the new meaning that Warhol’s changes had made to the work when weighing the first point of the fair use test. “Both courts below agreed and Goldsmith doesn’t dispute that Warhol’s Prince Series can reasonably be perceived to convey a fundamentally different meaning or message from Goldsmith’s photograph,” Roman Martinez, the foundation’s lawyer, told the justices. “The question in this case is whether that different meaning or message should play a role, any role, in the fair use analysis. Our answer is yes.”

That drew skeptical queries from some of the justices, who questioned how workable that analysis would be for the lower courts in practice. “How is a court to determine the purpose of meaning, the message or meaning of works of art like a photograph or a painting?” Justice Samuel Alito asked Martinez. “Should it receive testimony by the photographer and the artist? Do you call art critics as experts? How does a court go about doing this?” Martinez replied that those would be viable options, noting that courts have done similar things in other copyright cases.

While the immediate dispute between the foundation and Goldsmith is about one photograph, the Supreme Court’s ruling could ultimately determine how courts view fair use claims for a wide variety of copyrighted works. The justices appeared keenly aware of this as they tried to determine where to draw the line. Justice Elena Kagan noted that while this case dealt with a famous artist whose works’ meaning is well known, future cases involving future litigants could be harder to parse.

“If you imagine Andy Warhol as a struggling young artist, who we didn’t know anything about, and then you look at these two images, you might be tempted to say something like, ‘Well, I don’t get it,’” she told Martinez. “‘All he did was take somebody else’s photograph and put some color into it.’” Kagan added that the court “can’t always count on the fact that Andy Warhol is Andy Warhol to know how to make this inquiry.”

Goldsmith’s lawyers told the court that the foundation’s proposed test, which relies on meaning, “would decimate the art of photography by destroying the incentive to create the art in the first place.” They cited the friend of the court briefs filed by recording studios and other cultural heavyweights in her favor as proof of the broader impact that the court’s ruling could potentially have.

“[The foundation] responds [that] Warhol is a creative genius who imbued other people’s art with his own distinctive style,” Lisa Blatt, who argued for the plaintiffs, told the justices. “But Spielberg did the same for films and Jimi Hendrix for music. Those giants still needed licenses. Even Warhol followed the rules. When he did not take a picture himself, he paid the photographer. His foundation just failed to do so here.”

But some of the justices appeared unconvinced by this interpretation of the fair use doctrine. “It’s not just that Warhol has a different style,” Chief Justice John Roberts noted. “It’s that unlike Goldsmith’s photograph, Warhol sends a message about the depersonalization of modern culture and celebrity status and it goes through the different features to support that. So it’s not just a different style. It’s a different purpose. One is the commentary on modern society. The other is to show what Prince looks like.”

Others found that the first factor—the “purpose and character” one—might still cut against Warhol in this case even if meaning is incorporated into it. “Campbell’s Soup seems to me an easy case because the purpose of the use for Andy Warhol was not to sell tomato soup in the supermarket,” Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote, referring to the artist’s iconic series. “It was to induce a reaction from a viewer in a museum or in other settings. And the difficulty of this case is that this particular image is being used arguably for the same purpose: to identify an individual in a magazine in a commercial setting.”

The justices, for their part, sounded almost happy to discuss a legal issue that doesn’t carry major social or political weight. “Let’s say that I’m both a Prince fan, which I was in the eighties,” Justice Clarence Thomas began to say as part of a question. “No longer?” Kagan asked, to laughter in the courtroom. “Only on Thursday nights,” Thomas jokingly replied. Whether that jocularity will persist as now they try to figure out how to untangle the fair use questions in this case remains to be seen. A decision is expected before the end of the court’s term next June.