When President Barack Obama signed legislation in 2011 that raised the debt ceiling and imposed sweeping spending cuts, he argued that the “manufactured crisis” had served as “just one more impediment” to the nation’s post-recession economic recovery. That lengthy impasse had resulted in months of grueling negotiations, “something that we could have avoided entirely,” Obama said.

“Voters may have chosen divided government, but they sure didn’t vote for dysfunctional government,” he argued. Days later, Standard & Poor’s downgraded the country’s credit rating for the first time: Although the United States had not hit its borrowing cap, merely toeing the line of default had convinced the rating agency that “the effectiveness, stability, and predictability of American policymaking and political institutions have weakened.”

Twelve years after a Democratic president and a divided Congress reached that agreement, a similar dynamic has complicated the debt limit discussion. A newly emboldened House Republican majority, led by a speaker under pressure from his right flank—John Boehner in 2011, Kevin McCarthy today—is insisting that his conference cannot support raising the debt limit without spending cuts. President Joe Biden, who as vice president negotiated the 2011 agreement with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, wants the cap to be lifted without any caveats and with any discussion on spending cuts to be separately tied to budget negotiations.

With only a few weeks until June, when the Treasury Department predicts the U.S. will hit the limit, the two parties remain at loggerheads. Biden, McCarthy, McConnell, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy met for a largely unproductive discussion on Tuesday, leaving the Oval Office with entrenched positions and a pledge to convene again at the end of the week. “Everybody in this meeting reiterated the positions they were at,” McCarthy said after the meeting. “I didn’t see any new movement.”

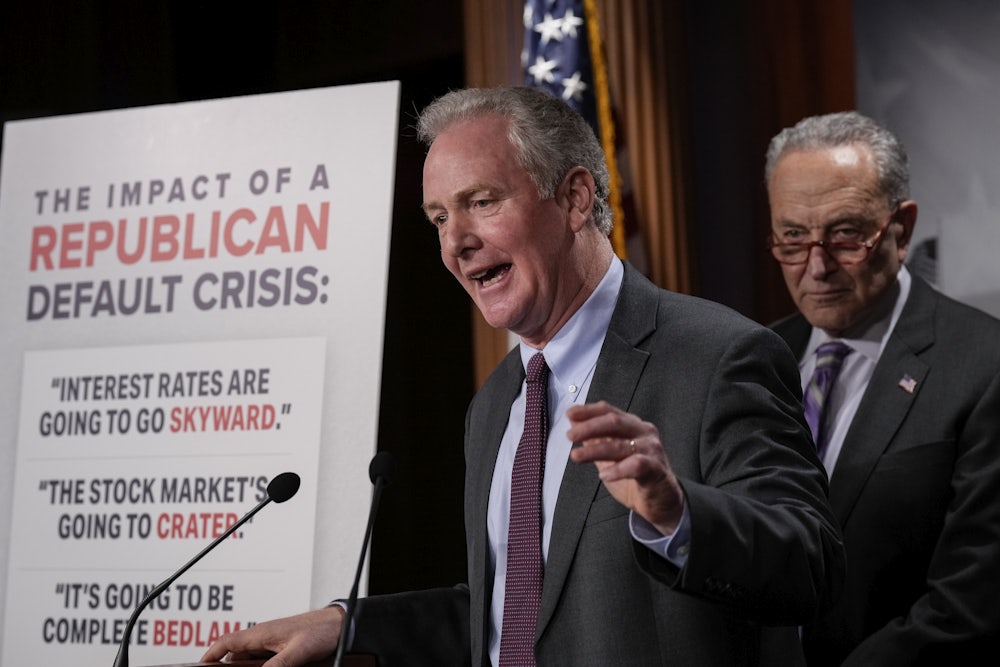

There are some key differences between the current situation and the crisis in 2011. McCarthy, who underwent 15 votes to be elected speaker, is contending with a five-seat majority, rather than the 35-seat margin that Boehner enjoyed. Senator Chris Van Hollen, who served as the ranking member of the House Budget Committee during the 2011 impasse, told me that he saw some similarities but called it a “more dangerous situation.”

“We have a weaker speaker in the House. We have more members in the Republican caucus in the House that seem willing to allow us to default,” Van Hollen said. “In terms of similarities, yes, there are some, but I’m much more worried.”

Moreover, McConnell has thus far expressed unwillingness to engage directly in negotiations, arguing that any agreement needs to be hammered out between Biden and McCarthy. “I don’t think Senator McConnell wants to undercut the House,” GOP Senator John Cornyn told me, identifying that dynamic as a major change between 2011 and the current situation. “I think what’s going to happen is President Biden is going to have to cave, but we’re going to have a lot of wailing and gnashing of teeth in the interim.”

But the most significant difference between the current stalemate and that of 12 years ago may be increased political polarization. In recent years, Republican elected officials have moved further to the right than Democrats have to the left. “The brinkmanship, this go-around, is lining up to be as chaotic, if not more, than the 2011 debt limit debate,” said Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. “The nation’s politics are more fractured today than they were a decade or so ago.”

Representative Steve Womack, the chair of the financial services subcommittee on the House Appropriations Committee, told me that the far smaller Republican majority was a key difference between the current stalemate and the situation in 2011, as was the increased polarization in the modern Congress.

“It makes it more difficult. Everything’s a weapon,” Womack said. The Arkansas Republican, who had called on Congress to address the debt ceiling last year, also noted that “Congress doesn’t get terribly excited about even some of the more significant issues until we’re looking over a cliff.” But Womack also faulted Biden for not being willing to negotiate on spending, a sentiment echoed by other Republicans in the House during the 2011 fight. Eric Cantor, the House majority whip at the time, told The Atlantic earlier this month that “President Biden is not the same person as Vice President Biden was.”

The Bipartisan Policy Center predicted this week that the “X date”—the date on which the U.S. is no longer able to fulfill its obligations—will likely fall between early June and early August. The think tank, which specializes in predicting the X date, noted that default could mean billions of dollars in missed payments for Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, veterans’ benefits, military and federal salaries, and food assistance programs. “I still don’t think now is the time for panic. But it’s certainly time to start getting concerned,” said Shai Akabas, the director of economic policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center, in a briefing with reporters on Monday.

Zandi worried that “investors think they’ve seen this movie before”—that is, Wall Street isn’t yet freaking out about the threat of default because it’s witnessed multiple debt limit showdowns in the past decade that have always been resolved, even at the last second. “I suspect that we’re not going to see a deal until there’s a lot of pressure coming from the markets, until stock prices are down, interest rates are up, and the dollar is under pressure,” Zandi predicted. Right now, investors are “inured” to fights over the debt limit.

“Not that they know how we’re going to get from A to Z, but they think with certainty, we’re going to get to Z. And by so doing, ironically, this raises the odds that we will never get to Z—at least not gracefully,” Zandi said.